Delcy Morelos: Working with Soil to Free the Soul

The Colombian artist focuses on unlocking the creative and spiritual power of geometry, color, and the land.

Julián Sánchez González, Delcy Morelos

May 25, 2023

This year, MoMA’s Cisneros Institute embarks on a new research project: Bridging the Sacred: Spiritual Streams in Twentieth Century Latin American and Caribbean Art, 1920–1970. Artists and specialists from Latin America and the Caribbean will convene in a series of conversations, gatherings, and publications around modern art and spirituality, with a particular interest in Afro-Diasporic, Indigenous, occult, Jewish, and Catholic traditions.

To launch this project, we spoke with Colombian artist Delcy Morelos. Since the 1990s, she has created a multimedia body of work in which reflections on life and death meet the natural and the sacred. Her most recent installations have used soil as raw material, inviting us to roam labyrinthine spaces that stimulate our senses. In our conversation below, we spoke about the different spiritual references in her work, and her own call to build a more sustainable relationship between humanity and the environment.

Este artículo está disponible en español.

Translated from Spanish by Ángela Sarmiento Romero

Delcy Morelos.

Julián Sánchez González: Delcy, the soil as raw material has been the starting point of your installations for over a decade. What process led you to work with this material?

At the beginning, my work was mostly focused on finding the origins of the violence in my country: racism, the glaring social divide, and the ravenous ambition of landlords to expand their already large estates. These dynamics stripped rural people of their small plots while threatening them with death, with statements such as, “If you don’t sell us your land, we’ll buy your widow.” The land is still an element in dispute in the armed conflict; it is an obsession that triggers inequality, and it is the booty of all wars. The land is the first asset we seek to possess, yet we turn it into an evil that unleashes violence. I soon began to wonder how to approach the land through different inquiries, and how to address such a pure and vital matter with reverence and awe.

What is the role of color in your work?

Delcy Morelos. Rojos por naturaleza. 1995.

“I felt that red was not just a color—I perceived it as a substance in itself which emanated from my fingers.”

I was obsessed with the color red for a long time. At times, as I painted, like when I did Rojos por naturaleza (1995), I felt that red was not just a color—I perceived it as a substance in itself which emanated from my fingers. I was close to making the radical decision to only paint with red for the rest of my life, but then I started working with soil.

Soil can have many colors: blue, green-gray, light brown, dark brown, yellow, ochre, orange, black, or red, due to its chemical composition. In my first works with soil, the soil is red. What makes soil red is the large amount of iron it contains, the same element that makes the blood that runs through our veins red. There is a deep relation between us humans and the earth, and we have lost awareness of that fact.

For the series Eva (2010), I used a very intense reddish-orange type of soil. Through this work, I started to discover and understand the deep connection between color, life, and the female body. The earth holds in its womb the very cycles of life, death, and rebirth, and it is a feminine divinity.

Delcy Morelos. Eva. 2013

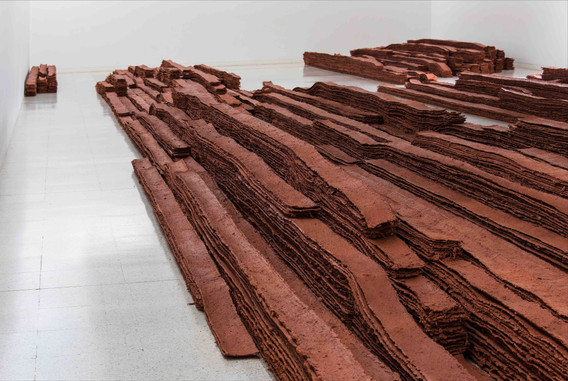

Delcy Morelos. Earthly Paradise. 2022

Earthly Paradise (2022) and El lugar del alma (2022) are large installations where the spectator “enters” the soil. What does this sensory confrontation mean to you?

Earthly Paradise, the installation I brought to the Venice Biennale in Arsenale—a place that was initially used to store weapons—is a penetrable, fragrant, receptive, feminine, and fertile sculpture. It is also an enabler of life. It occupies the space by creating a horizon of black mixed soil, scented and sweetened with alimentary and fragrant substances.

El lugar del alma, installed in the second basement of the Museo Moderno de Buenos Aires, 10 meters underground, is an experience where the spectator descends into the bowels of the earth and enters a sacred place to make her an offering. The Argentinian Andes ancestral tradition gives offerings to Pachamama, the place of the soul. Offerings to the earth are made with flavors: cinnamon, cloves, coffee, cocoa, and corn grains.

My desire and intention are for the spectator, by crossing that threshold, to enter the dimension of the sacred, of gestation, of fragility. The smell precedes and announces the experience, and the soil is the matter from which everything emerges and comes back to regenerate in the cycle of life and transformation.

Delcy Morelos. El lugar del alma. 2022

Delcy Morelos. No es un río, es una madre. 2014

No es un río, es una madre (2014) is a piece that shows us your connection to Indigenous cosmogonies. How do these inform your work?

I was born by the riverside of Sinú, a land fertilized by the river’s floodings. Twenty-five years ago, that mother-river was imprisoned and massacred by the construction of a large hydroelectric power plant, Urrá. The first to suffer such agonies are the locals. The Embera Indigenous people, angered and saddened, decided to say goodbye to their mother, source of nourishment and life, by embarking on a journey in small canoes from the source of the river in the mountains, at the Nudo de Paramillo, to its mouth in the Caribbean Sea, in Bocas de Ceniza. The canoes held precarious cardboard signs with writings of reverence and love. One of them read: “She is not a river, she is a mother,” showing that they know something that we, having gone through consecutive industrial revolutions, have forgotten.

As a woman and an artist, I always stop to listen to the ancestral words and the wisdom that come from the Amazon rainforest or the mud and stone huts on the peaks of the Andes. This wisdom has been flowing like a river for hundreds of years through grandfathers, grandmothers, taitas, and curanderos.1 They are heirs to the knowledge contained in oral accounts, ceremonies, and rituals. What this knowledge shows us is how to communicate with the earth, the plants, the river, the mountain, the wind, the fire, the sun, and the moon; how we integrate that planetary and cosmic flow into our human cycles. It is through this vision of the world that we realize how the human tissue is intertwined with voices: that of the ancestors, the spirits of the mountain, the rainforest, the desert, and the ocean.

What relationship do you have with the archetype of the witch and the curandera, and how does it feed into your art?

To me, the feminine does not refer to sexual organs; it refers to a structure and a way of engaging with the world from certain specific interests: listening, nourishing, caring, the unconscious, harmony, connectivity, emotion, knowledge acquired from instinct and bodily experience. This feminine approach can be cultivated by any gender as it is, in my view, a human tendency and, furthermore, a vital one.

The witch, the woman, has always been a symbol of the type of knowledge that seeks to care for and get to know the natural world, its laws, cycles, and secrets, all powerful knowledge that the patriarchy has repressed and denigrated. The curandera knows she is taking care of herself when she takes care of her equals and her natural environment, and when she interacts with nature, as she knows she is a part of it. Feminine healing practices integrate the body with the emotions, the mind with the spirit, and they vindicate processes of self-healing and patience as ways to ally with the wisdom of the passage of time.

These archetypes have been misinterpreted and rejected, and they were burned at the stake. That is the extent of blindness, ignorance, and prejudice. The fear and arrogance—they go hand in hand—of the patriarchal labyrinth have destroyed our ancestral connection with nature. I acknowledge myself and I act from these archetypes of the female psyche, because through them I can interact in a way that is receptive and intuitive of the creative adventure.

Your work operates on two opposite poles: abjection and healing. What does this duality tell us about your way of seeing the world?

When you can look your fears in the eye, the healing process begins. Therefore, exposing the problem is part of the healing—they are two ends of the same thread. My Amazonian philosophy teacher, the native Uitoto Isaías Román, says: “In the universe, everything is knitted like a wicker basket: opposites intertwine in ever-closer knots until they can hold water.” Polar opposites intertwine into a fabric where there is no separation, and we all are, along with everything that exists, threads of that fabric that receives, contains, and constantly weaves itself.

Related articles

-

Tomás Saraceno Takes On the Challenge

The artist charges forward to stop lithium mining in his home country.

Inés Katzenstein

Apr 20, 2023

-

José Bedia, a Cuban Artist Collecting the Intangible

The artist guides us through his collection of art and ceremonial objects, and how it has influenced his own work.

José Bedia, Julián Sánchez González

Mar 22, 2023