José Bedia, a Cuban Artist Collecting the Intangible

The artist guides us through his collection of art and ceremonial objects, and how it has influenced his own work.

José Bedia, Julián Sánchez González

Mar 22, 2023

José Bedia

Starting this year, MoMA’s Cisneros Institute introduces a new research project: Bridging the Sacred: Spiritual Streams in Twentieth Century Latin American Art and Caribbean Art, 1920–1970. In dialogue with specialists from Latin America and the Caribbean, the project seeks to investigate relationships between modern art and spiritualities throughout the region, with a special interest in Afro-Diasporic, Indigenous, occult, Jewish, and Catholic traditions. A series of publications and gatherings exploring this theme will be held beginning this year.

To mark the project’s launch, we spoke with Cuban artist José Bedia, who since the 1980s has been one of his country’s most prominent artistic figures. Bedia’s work reflects his interest in building relationships between Indigenous and Afro-Diasporic spiritual systems. Alongside his art practice, which spans four decades, Bedia is an avid collector of ritualistic and ceremonial art, as well as the work of self-taught artists. This lesser-known facet of the Cuban artist’s world is the focus of this interview.

Este artículo está disponible en español.

Translated from Spanish by Carolina Fernandez Del Dago

Julián Sánchez González: José, when I first visited your collection in 2020, we spoke about the ways in which your artwork and collecting are intertwined. Tell us about this relationship and how your collection began.

José Bedia: My work and my collection have been together since the beginning. This happened spontaneously while I began studying art since, back then, I felt dissatisfied with the fact that art education was oriented solely toward the history of Western art in all of its aspects. Artistic production from other cultures was not mentioned at all, so I decided to provide myself with information and make up for that deficit. First I focused on Cuba’s Indigenous archaeology, moving on to search for ethnographic objects from Africa and Oceania.

José Bedia’s collection in his home in Miami

In your collection, artistic and ceremonial objects from various cultures converge in the same space—your home. What have you learned from living with these objects?

I have a rather unique method. I’m interested in surrounding myself with objects that I consider to be on the same artistic wavelength as my work. They end up being visual supports for my thesis or proposal, and I also receive their influence every day in the most natural way possible. Oftentimes, this isn’t a strictly formal bond, but rather a way to keep resources and solutions I admire close by. This collection functions as a library of permanently open books—they are at my reach and available at all times.

A Chokwe Yakisekula, or divination basket, from Congo

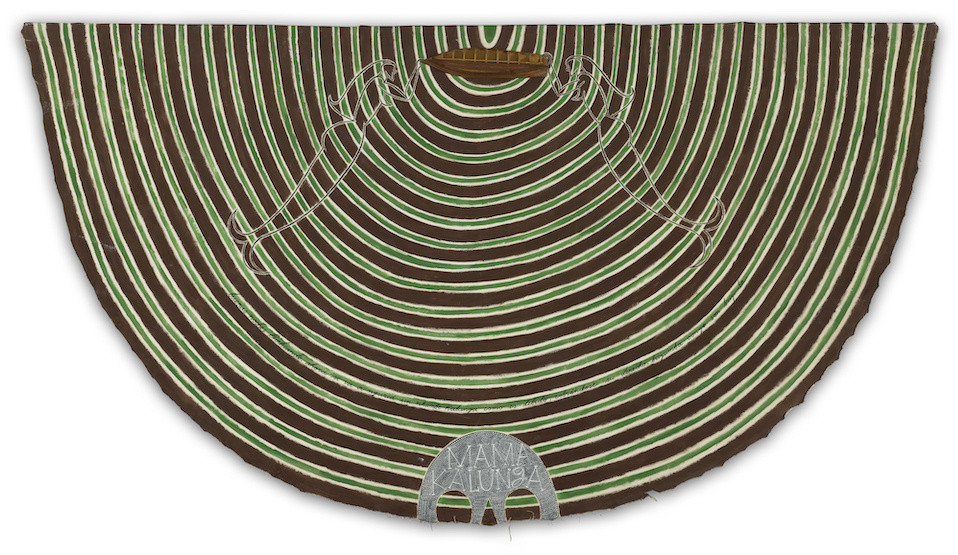

José Bedia. Mamá Kalunga. 1992

In April, as part of the exhibition Chosen Memories: Contemporary Latin American Art from the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Gift and Beyond, your work Mamá Kalunga (1992) will be exhibited at MoMA. What is this piece about and how is it related to your collection?

Mamá Kalunga is directly related to the Conga (Bantus) traditions of my country. The piece is the lower half of the Congo universe’s cosmogram, which refers to everything below the Kalunga line (in this case the horizon) and corresponds to the underworld. Two mermaids are depicted sinking a boat to the bottom of the sea, where a large human skull is seen. The concentric lines suggest a progressive downward force. There is a text written in both Spanish and Kikongo (in Palmer calligraphy) that mentions the sea deity’s right to take possession of anything that crosses over her. There is also a reference to the fate of the immigrants who come by sea, who tragically disappear in the crossing.

Masks, objects that allow the alteration of one’s own perception, play an important role in both your work and your collection. What might these pieces tell us about current discussions around identity politics?

I find it curious that most of the objects in my collection are three-dimensional and mostly masks, while my work is mainly two-dimensional. I have always been an advocate for the value of these objects, not only as a specific group’s heritage, but as humanity’s heritage. At this point, we’re all involved, and in addition to being a collector, my role is to disseminate these values and to ideally give them a safe home. This is one of my main goals.

José Bedia and a Holo mask used for the Mukanda initiation ceremony in Kwango Kuilo, Congo

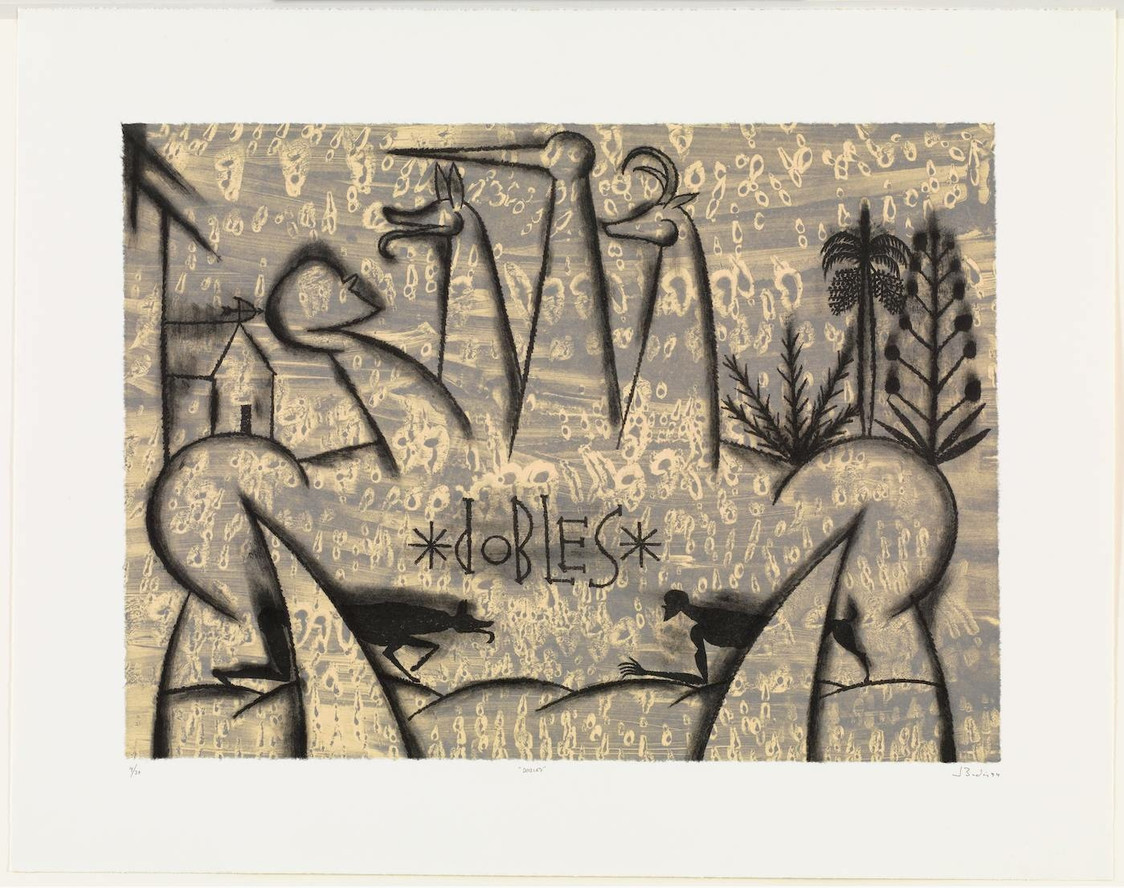

José Bedia. Dobles. 1994

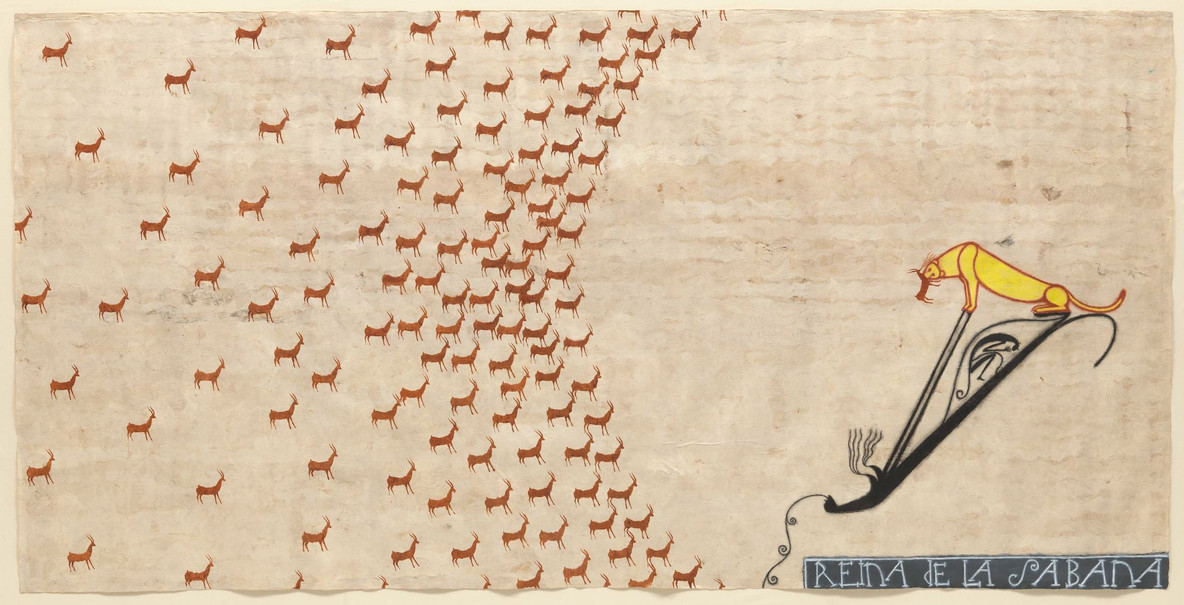

José Bedia. Reina de la Sabana. 2001

In January, the second retrospective of your work opened at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Monterrey in Mexico. In connection with this exhibit, I wanted to ask you about whether your relationship with the art that you collect has changed over the course of your career.

I don’t think there have been substantial changes. In fact, the retrospective is titled Circular Voyage, alluding to my journey through an eternal inner circle of ideas that, from time to time, signal highlights or milestones. In this case, my retrospective is supported by tribal objects interspersed throughout the show, that help the viewer see the direction in which I am headed.

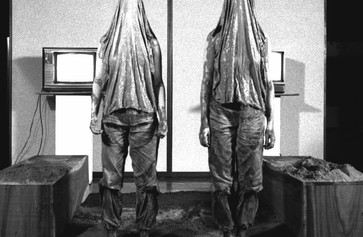

José Bedia’s collection in his Miami home. At left, a shaman dress from Mongolia

Set of Cora votive arrows intended to call rain, from Nayarit, Mexico

Collections like yours play an important role in the preservation of the ancestral knowledge of Latin America and the Caribbean. As a collector, how do you see your work in relation to the current debates about the repatriation of museum collections?

My goal is to see all of these objects preserved and publicly available at an institution that would embrace them, though for the time being, this is out of my hands. Beyond taking care of my own work, my skills are very limited. This would require interdisciplinary teamwork.

As for possible repatriations, I don’t see anything in my collection qualifying for this category. Of course, there is a debate about the property rights to many objects housed in institutions and museums. Of course, there have been cases of theft, but that’s not always true in every instance, so we should be careful about each particular case.

Similarly, we cannot forget that if we know about these cultures today, it’s because someone brought them to a public that now knows and appreciates them. As a general rule, many of these heritage objects have been preserved in museums and institutions far from their places of origin. In the future, It would be ideal for the countries and territories where the pieces originate to provide them with safe homes. Unfortunately, so far the conditions for this happening haven’t been favorable.

Related articles

-

On the B-Side of Modernity: An Interview with Iosu Aramburu

We visited the artist’s studio to discuss his open-ended installation Atlas of Andean Modernism and other projects.

Iosu Aramburu, Elise Chagas

Dec 28, 2022

-

Perception That Opens Like a Memory: An Interview with Yeni & Nan

The artists discuss their early performances, art in Caracas in the 1980s, and opening up cellular memory.

Nan González, Yeni Hackshaw, Madeline Murphy Turner, Elise Chagas

Apr 28, 2022