Tomás Saraceno Takes On the Challenge

The artist charges forward to stop lithium mining in his home country.

Inés Katzenstein

Apr 20, 2023

In 2020, starting from the Salinas Grandes salt flat in the Northern Argentine province of Jujuy, artist Tomás Saraceno led the world’s first manned, solar-powered free flight, setting 32 world records. The flight also highlighted the region’s environmental struggles; members of more than 30 local indigenous communities attended the event. Eventually, Saraceno named the project Fly with Aerocene Pacha, referring to Pachamama, the Mother Earth of the Indigenous communities in the Andes. Pilot Leticia Noemi Marqués flew the large black balloon above the white surface of the Salinas for 16 minutes, along with a large sign that read, “Water and Life Are Worth More than Lithium,” referring to the environmental and social damage caused by lithium extraction in the region. We recently spoke with Saraceno about his groundbreaking project.

Este artículo está disponible en español.

Pacha, from the film series Fly with Aerocene Pacha. 2020

Inés Katzenstein: This year you decided to go back to Jujuy, this time to engage even more directly with the communities. Your project articulated their experiences and struggles in a film, and included a small group of environmentalists, writers, lawyers, and me. Can you share with us how you decided on this activist orientation for the Pacha project?

Tomás Saraceno: We have had a relationship with the Indigenous communities of the Salinas Grandes and Laguna de Guayatatoc basin for many years now. It has always been more a matter of listening, of understanding the urgencies and alternatives they are proposing. Since last year, when the government of Jujuy intensified their efforts to extract and export lithium, one could feel that urgency increasing. At the same time, I was invited to do an exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in London, and I started thinking that I wanted to go back to the Salinas.

Pacha, the never-ending film that we began in 2017 remains a work in progress, which is a beautiful thing. With each screening, a new version emerges from the exchange of stories, thoughts, arguments, ideas, and hopes with the audience. Until now, Pacha has had only a few screenings—it was never discussed as a piece in an institutional setting, because I felt a personal commitment to share it with the communities in Salinas first. Because of the pandemic, we hadn’t been able to experience it together, so one of the reasons for going there this time was to organize a gathering that was both a screening and part of the film as it continues to develop. It was incredibly moving to finally watch it with these people, many of whom share their stories and testimonies in the film. I have never experienced such emotional feedback as I did after this screening. We hugged, cried, and applauded together for 10 minutes.

What made this experience both exciting and challenging is that it invited new life into the filmmaking process, imagining a film not as an end in itself, but as a constantly evolving, ever-changing thing that morphs to the shape of the communities represented in it. Getting their feedback was a priority, because it is one thing to facilitate broader visibility for a community and its struggles, and another to actually involve that community in the process of this film. Otherwise we continue with this extractivist-colonialist logic of images, of knowledge. Because of the intensification of the national and provincial governments’ push for lithium mining, this time Aerocene returned with more people and other environmental collectives who are supporting the communities and sharing legal, academic, and artistic strategies.

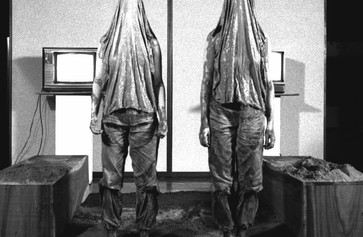

Aerocene sculpture. 2023

Can you talk about the impact that lithium mining is having on the area?

Today, almost all of Argentina’s salt flats are under what is known as a pedimento: the process by which private companies, often multinationals from the United States or Australia that claim to have “discovered” a lithium deposit, get permission from the provincial mining authorities to extract and commercialize the mineral. There are already 60 such projects in the provinces of Salta, Catamarca, and Jujuy.

One of the main problems with lithium mining is that it is water mining. In the Salinas Grandes, over 90% of fresh water is held in underground veins of “fossil water.” In an area heavily affected by drought, this water is precious. Yet the evaporation process used in mining lithium requires huge amounts of it: extracting one ton of lithium requires two million liters of water. It is a sad truth that water has become a commodity—perhaps it is high time that these companies pay for the water they use as well as the lithium they extract. The local communities have been continuously fighting to stop exploration and extraction projects from moving forward, arguing in defense of the basin’s fragile ecosystem as well as for respect of their ancestral practice of salt harvesting and the principle of reciprocity it is based on. So far, the communities have been successful—they even brought the case to the Interamerican Court of Human Rights and the United Nations.

What is your idea for this film?

We call it a film without an end—a film without the need for a filmmaker and actors, almost a performance. How might a film without a camera affect people psychologically, especially with this addiction to screens that some of us have? Can we make a film without knowing what to film? It is a process of constant evolution.

The first chapter started in 2017, when we first went to the Salinas Grandes; continued when we returned in 2020 as part of CONNECT: BTS, a global event organized by the Korean pop band BTS and curated by DaeHyung Lee; and continues now in 2023. Inadvertently, I became well known among BTS fans. When we went there for the Fly with Aerocene Pacha project, I couldn’t believe the combination of BTS fans, singing and dancing in Korean in the middle of the salt lake, local copla singers all eating locro and empanadas and participating in rituals of thanks to the Pachamama, and Leticia Marqués taking off as if in a different ceremony—it was surreal! But it’s simple really: to take off and land you need ground, and it’s impossible if this ground is taken over by corporations. We can not take off and land from a pool filled with water.

How has your experimentation with flying developed since that first flight?

In Salinas Grandes, Leticia was able to fly alone. We hope that the next prototype, which we are testing now, will carry two to three people. More passengers requires a larger sculpture. We have just tested it with pilot Lea Zeberli and other members of the Aerocene community in Maintenon, France, where we flew with the messages “Fly Free from Fossil Fuels,” “Stop Wars! Peace Now!,” and “Water and Life Are Worth More Than Lithium,” written with the communities of Salinas Grandes and Laguna de Guayatayoc. The first sculpture had a volume of 2,000 cubic meters; the next one will be close to 7,000 cubic meters, meaning more people will be able to fly completely free from carbon and fossil fuels. This holds immense significance for the future of air. Together, we continue to move away from today’s borders and the fossil fuel regimes by experimenting with lighter, more affordable, and more sustainable materials, because in a world facing a climate emergency, the dream of flight has become a nightmare. There are 1.3 million people in the air at any given time, releasing over one billion tons of CO2. Planes have become petro-capitalist flying cities polluting the air that we all should be sharing.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic brought about a moment of stillness—something we call stillness in motion—on a planetary scale. The sudden drop-off in industrial activity created the longest global anthropogenic seismic noise reduction on record, with levels reduced by up to 50%! It was an opportunity to attune to the rhythms of both planetary and terrestrial bodies, for us to detect subtle signals from underground seismic sources that were concealed in noisier times. You could almost feel the Earth flying at 67,000 miles per hour, zooming around the sun—and I do mean feel and not hear! And now, though it seems this pandemic is far from over, we are banding back together and returning to what was thought to be closed for so many: as researcher and activist Maristella Svampa might say, we are returning to a portal of hope.

What does this hope rest on?

A large part of the spirit of my practice is motivated by a do-it-together, ethos—humans, non-humans, and more-than-humans coming together to create things at the margin of the formalized, hierarchical structures of capital, understanding that there is no Plan(et) B. Despite what tech entrepreneurs may want us to think, the focus should be on exploring alternative ways of living and flying on the planet we do have, not leaving it behind for other planets to destroy.

With this new project you are questioning the popular narrative about lithium being the key to a radical, clean transformation of transportation systems. And you are pointing out the social and ecological consequences of its extraction. How has knowing about the injustices inherent in the “Green transition” transformed your thinking about the future of human mobility?

Technologies and new energy regimes cannot be detached from the social dynamics that they are a part of. This is why Maristella Svampa has used the term “eco-social transition.” Currently, the energy transition in the North is being paid for by countries in the South—especially by Indigenous and rural communities. It is reproducing the same neocolonial, extractivist, and displacing politics that we have seen for the past 500 years. At a different time, Felix Guattari wrote about this in The Three Ecologies, in which he argued that we cannot separate mental, social, and environmental ecologies. It is time to bring these ideas together—from philosophy, law, sociology, economics—to create collective, open-source dialogues and solutions that we can all participate in to face this climate emergency.

Maybe we need to begin to think of the ecosystems we inhabit as artworks—radical experiments in co-creation and coexisting.

Members of the Indigenous communities of Salinas Grandes and Laguna de Guayatayoc demonstrate against ongoing lithium extraction, 2023

Related articles

-

José Bedia, a Cuban Artist Collecting the Intangible

The artist guides us through his collection of art and ceremonial objects, and how it has influenced his own work.

José Bedia, Julián Sánchez González

Mar 22, 2023

-

Perception That Opens Like a Memory: An Interview with Yeni & Nan

The artists discuss their early performances, art in Caracas in the 1980s, and opening up cellular memory.

Nan González, Yeni Hackshaw, Madeline Murphy Turner, Elise Chagas

Apr 28, 2022