Didier William: Opaque Bodies/Spiritual Futures

The Haitian American artist reflects on his recent work and MoMA’s collection of Haitian art.

Julián Sánchez González, Didier William

Nov 6, 2023

This year, MoMA’s Cisneros Institute embarked on a new research project: Bridging the Sacred: Spiritual Streams in Twentieth Century Latin American and Caribbean Art, 1920–1970. Artists and specialists from Latin America and the Caribbean will convene in a series of conversations, gatherings, and publications around modern art and spirituality, with a particular focus on Afro-diasporic, Indigenous, occult, Jewish, and Catholic traditions.

As part of a series of interviews related to this project, we spoke with Haitian American artist Didier William. We invited Didier to reflect on his recent work and exhibitions, as well as on MoMA’s collection of modern Haitian art. In this conversation, the artist takes us through the challenges of collecting and exhibiting Caribbean art and artists, including work grounded in the Vodou religion. His view reaffirms and reclaims art practices and spiritual beliefs that had been hidden in order to survive, and that are now finding public appreciation in the Caribbean and beyond.

Este artículo está disponible en español.

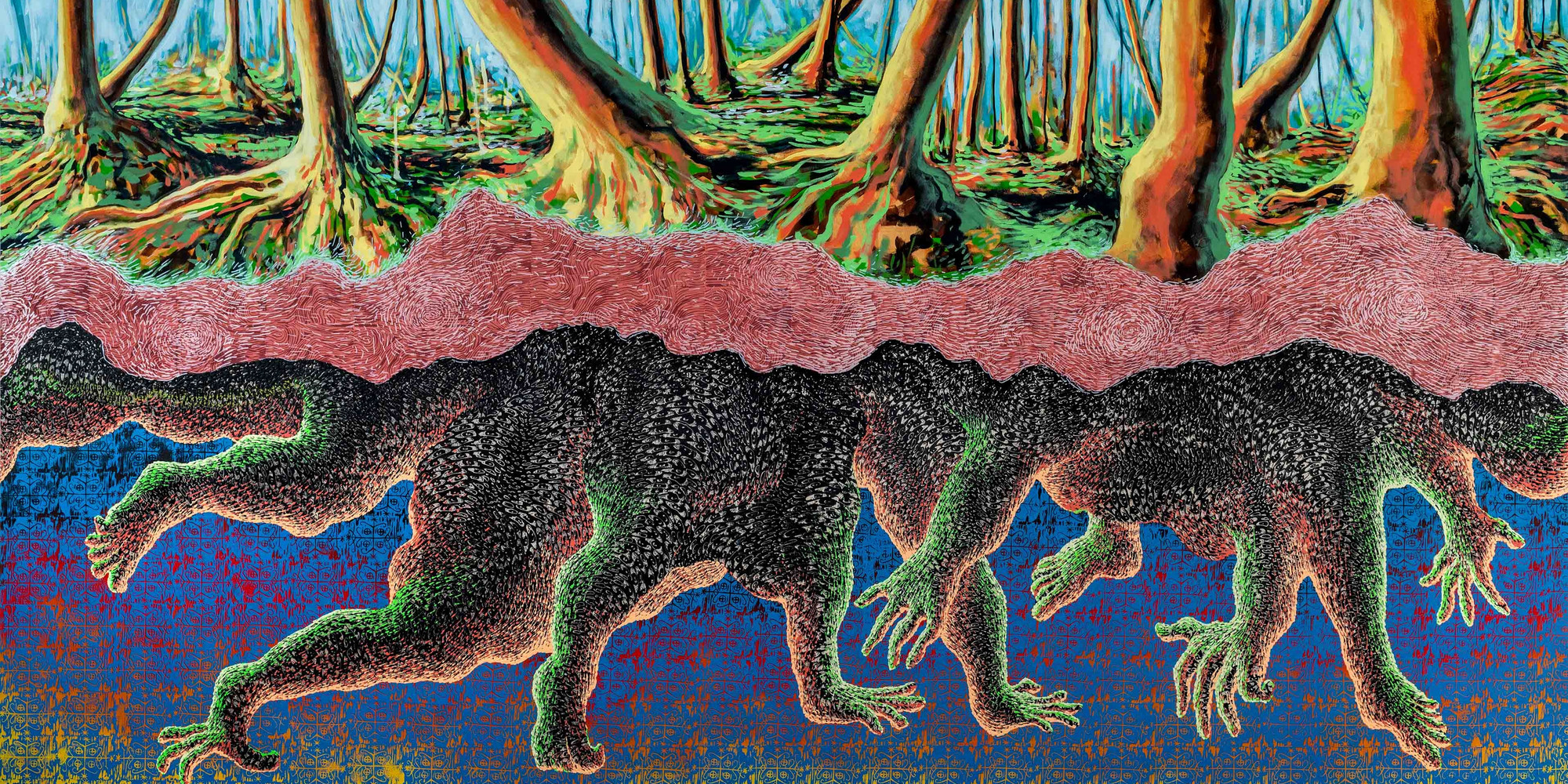

Didier William. Poto Mitan 2. 2022

Julián Sánchez González: Haitian art and artists have been claiming more visibility and space in the contemporary art world. What’s your perception of Caribbean and Haitian art collection building over the course of the last decades?

Didier William: This begs the question of what museums think the Caribbean is, and the kind of othering that gets projected on the Caribbean. Having said that, I think that it is amazing and impressive to see more and more institutions today becoming interested in the richness, the histories, and stories that come out of the Caribbean. I am thinking about artists who are making work about mythology, science, geography, and politics, which is a shift away from the typical depictions of a beach scene or women with large baskets on their heads or men with machetes cutting down sugar cane. Or, conversely, about the blighted postcolonial wasteland that the West often thinks we inhabit. There is this full spectrum in between that presents a complex humanity that is not just about a Western gaze on a tropical paradise. As someone who was born in the Caribbean, in Haiti, but grew up in the US, I am looking at what happens to a Haitianness, a Caribbeanness, that is not bound by geography. What are the historical, mythological, personal, maybe even cosmic resonances that stay and that get built up when nationhood and geography are partially taken away? How do we find a truth in that? It is encouraging to see museums starting to do this work as well.

Vodou religion has been at the center of Haitian cultural expression. How has the understanding of Vodou changed?

When my family moved to the United States in 1989, no one was affirmatively identifying themselves as Haitian in South Florida. You simply didn’t talk about Vodou. Even today, conservative Haitians blame Vodou for the country’s struggles. But then there are those of us who see it as an intrinsic, very intimate part of who we are on a cellular level. Vodou can’t be disentangled from how you understand Haiti and its history as the largest colony of Blacks stolen from the African continent, an aspect critical to its success as a sugar plantation. Enslaved Africans maintained the worship rituals that they brought with them, allowing them to have a sense of community and collective identity in the face of the horrors of colonization inflicted by the French, British, Germans, and Americans. That was the path to salvation and liberation for Haiti, so you can’t remove Vodou from the country’s identity and expect to understand Haiti and its trajectory since 1791, when the Revolution began.

This religion is intimately tied to who we are personally and nationally. This intimacy crosses collective and individual boundaries, and in some cases also serves as a container and archive for historical, familiar, and personal memory, even after death. My piece Poto Mitan 2, which is a sculpture at a recent Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami exhibition is about this very idea. The body acts as the historical container that builds up the poto, or pole center. This would normally be something like a living tree, but in my work it was a tower of bodies that hovered in the middle of the exhibition. For my family, and for many families that emigrated to the United States and elsewhere in the West, the poto mitan illustrates how we retain our sense of self and our proximity to those who have passed.

Préfète Duffaut. Sin. 1953

MoMA’s collection includes mid-20th-century paintings and sculptures by major Haitian artists. What kind of sentiments, for instance, do works like Préfète Duffaut’s Sin evoke in you?

When looking at this painting, the idea of holding this monumental moment in spirituality and religion as a small worship object is really interesting to me. I’m also thinking about Erzulie a lot when I look at this work, particularly Erzulie Danto, the motherly loa, or spirit of love, in the Vodou religion—as this phenomenal romantic figure, but also as a tragic, vengeful figure who sits pretty heavily in a lot of my work. It is interesting that the ground in the painting is so one-dimensional, when the rest of the painting becomes almost a tessellation, pieced together like a puzzle. I find myself going back to that sense of deep, heavy gravity in the work, which is pulling down the branches, literally holding down the figures, whereas everything else is flamboyant and expressive.

What are your thoughts on Jacques-Enguérrand Gourgue’s Magic Table?

I love this one because earlier on I was thinking about the characters or figures in my paintings being creatures more than humans, something larger. In an essay, Zoé Samudzi called them “titans,” which I really loved. In Haiti, and in Haitian Vodou especially, during worship and ceremony, the belief is that the body transcends into another space that allows it more agency, more liberation, more ability. There is a sense that the body can subvert gravity and perform superhuman acts, and this painting takes me there at every level. There is this main event, but then as you zoom in closer and closer to different parts of the work, there are equally epic sub-narratives taking place within all the characters. I’m very impacted by this painting; it stuck with me.

Can you say more about the notion of bodily transgression in these works, as well as in your work?

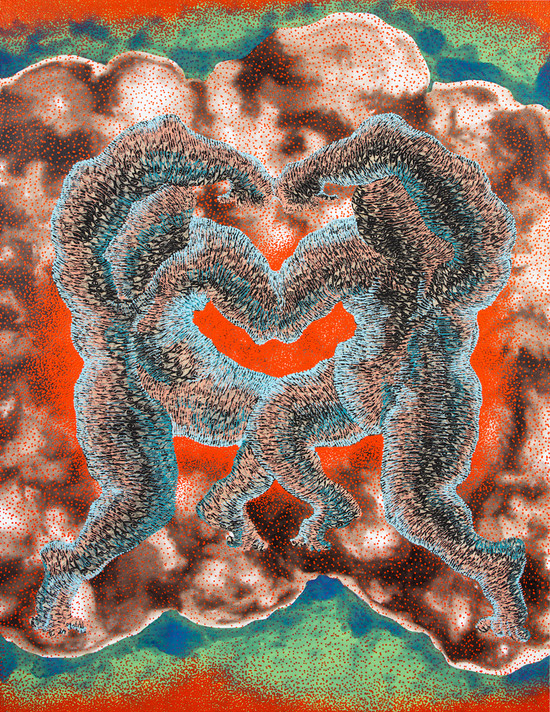

It is interesting to think about imagining alternative states of being for anyone whose body has been criminalized, and not just in the context of the Caribbean, but for those of us who have tried to occupy bodies that have not been able to live freely in real time. A piece of mine, Kisa n’ap fe ansamn, which means “what we would make together,” comes to mind. This is a painting that I finished around November of 2019, when my husband and I were expecting our daughter, with the help of a surrogate, which was a moment when I was thinking a lot about the union that was bringing this new person into the world. There was a beautiful way in which our bodies and the surrogate’s body had to transgress the conventions assigned to them and bring this new life into being. This sat with me for a long time and I thought about how I wanted to make a painting about it. But knowing how I work, I wasn’t going to sit my husband down and make a portrait of him or me. So, what came to mind was these two figures joined at the arms and the legs, and in the center was this glowing heart-shaped energy—one of the most sentimental paintings I’ve made. It reflected the same idea—of the body moving beyond itself and doing something for itself, its perpetuity, its futurity.

Didier William. Kisa n’ap fe ansamn. 2020

Didier William. Baptism: We Cannot Drown, Nou Beni. 2022

Baptism: We Cannot Drown, Nou Beni is a work where I was thinking about the Caribbean Sea, a body of water between Haiti and the United States, as a type of baptismal space. Instead of claiming the many bodies it has claimed on their journey to flee their country, this water becomes a superhuman fluid that actually produced titans or superhuman characters who could withstand something like myriad bolts of lightning.

In Dezabiye 2, on the other hand, the characters are beginning to uncloak their sight and they are beginning to present themselves without an armor of eyes, the motif my work is mostly known for. The eyes aren’t disappearing, they are becoming this other interlocutor, a kind of second character that the bodies can interact with and speak back to, becoming one of my first paintings of this nature. I started to think about the expulsion of energy that would happen when they are able to do that. What would it look like if these characters, who have been secured with this chainmail of eyes for a long time, finally removed it? Are they removing this armor willingly, intentionally? Are they encountering us when they remove it, or are they encountering each other?

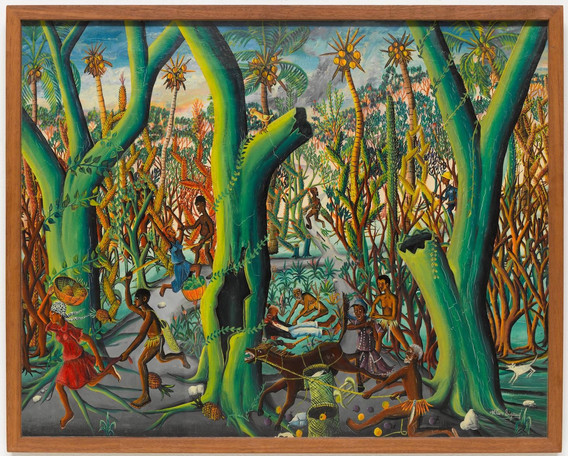

In Haitian modern art, depictions of nature play an important role, as is the case in Wilson Bigaud’s Murder in the Jungle. Do you find a resonance between this work and your Cursed Grounds series?

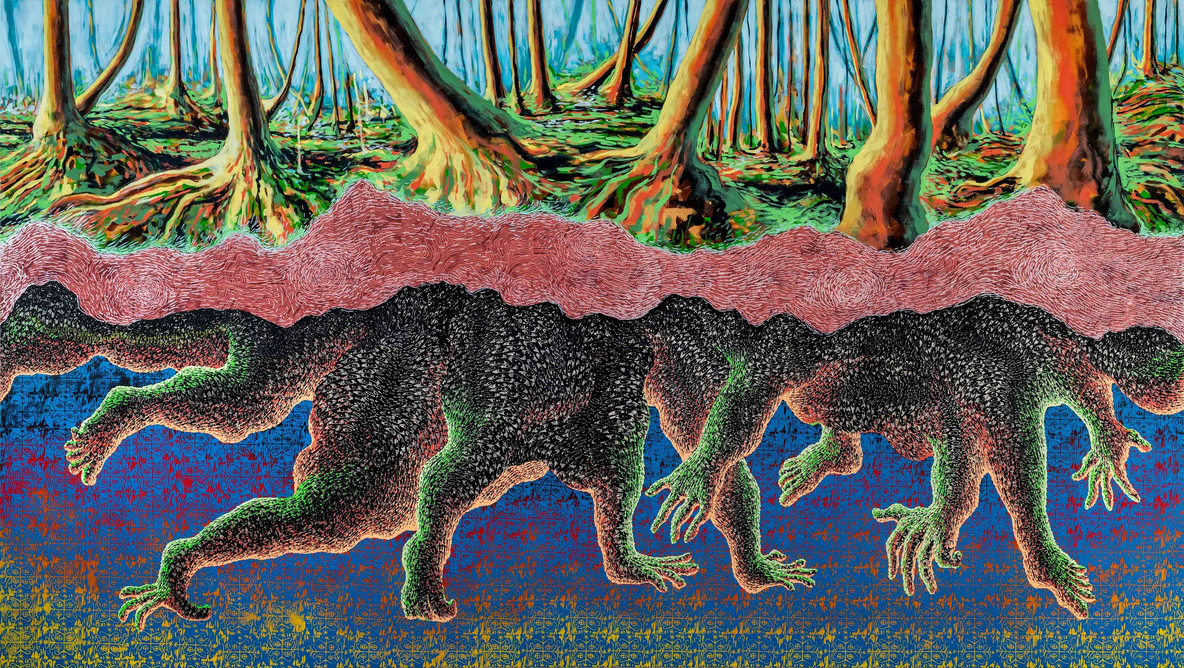

Connection to nature in Haitian art is well documented and researched. I find that Haitian artists have represented nature as an ally, and not necessarily as an adversary. I think of my own recent paintings depicting nature—which I sometimes call “groundscapes” instead of “landscapes”—as the continuation of that conversation. The Cursed Grounds series looks at spaces that have a deep history, and often these paintings don’t have any figures or characters in them—the character is the landscape and the ground. The first in the series looks at the Atchafalya Basin in New Orleans, part of the Louisiana Purchase territory, and its relationship to the Haitian Revolution. In the subsequent paintings, I have been looking at a few different spaces, including Lorimer Park in Pennsylvania, where we spent time with our daughter at the beginning of the pandemic. In some ways I am looking at the aftermath of scenes similar to the one represented in this Bigaud painting. What happens many generations later, when the space has been regrounded, replanted, gentrified, turned into luxury high-rises and manicured parks? How does this subterranean history remain? How do we continue these conversations about landscapes and nature, and about ground specifically? I am still thinking along those lines and looking at new spaces. I actually flew back down to New Orleans in October to do some more research around this idea.

Wilson Bigaud. Murder in the Jungle. 1950

Didier William. Cursed Grounds: Cursed Borders. 2021

What is your perception of art-making in Haiti today as it relates to Vodou beliefs and practices? What would be some of the benefits and perhaps some of the risks of tapping into this particular source of creativity?

I think the risk is being illegible, right? Though I would also ask, who are we trying to make ourselves legible to? We can think about Édouard Glissant and his affirmation of opacity in order to affirm ourselves to ourselves and for ourselves. I struggle to think about what the risk is there because in all the artists who we have mentioned, as well as other artists who are currently working, I am seeing thoughtful and creative makers who are opening up the narrative about who we are beyond the rigid institutional narratives that do not tell the full story and, in fact, represent a system of erasures more than any authoritative narrative.

A lot of these artists are thinking about mythology, fantasy, and storytelling, and so I think that there is a collective awareness that the world is in environmental, political, and economic trouble, and this is opening us up to think about potential futures in a way that hopefully gives us an alternative. It is no surprise to me that artists are looking to fantastical storytelling and mysticism, because these things that have been stigmatized in the past are actually making us more human than the rigid lies we have been holding on to for life. These are the lies that have left us with a climate crisis, the entire world making a hard-right turn, and poverty that we could not have imagined. We need to look at other modes of being, because that is what might save us and preserve the planet for our children. I don’t think this impulse is unique to Haitian artists or Caribbean artists; I think everybody is doing it.

Related articles

-

Weaving through the Threads of Life

Bolivian artist Elvira Espejo Ayca encourages us to view Andean textiles from the perspective of weavers.

Elvira Espejo Ayca, Horacio Ramos

Oct 4, 2023

-

The Life Cycles of Objects: An Interview with Adrián Villar Rojas

Take a closer look the artist’s work and its relationship with time.

Julia Detchon, Adrián Villar Rojas

Sep 5, 2023