When Video Games Came to the Museum

A decade ago, MoMA acquired 14 video games—and kicked off a new era for the collection. Today there are 36, and many are in the exhibition Never Alone.

Paola Antonelli, Paul Galloway

Nov 3, 2022

This article, presented on the occasion of the exhibition Never Alone: Video Games and Other Interactive Design, reprints a pair of posts that originally appeared on Inside/Out: A MoMA/MoMA PS1 Blog on November 29, 2012, and June 28, 2013, by Paola Antonelli and Paul Galloway, respectively.

Video Games: 14 in the Collection, for Starters

November 29, 2012

We are very proud to announce that MoMA has acquired a selection of 14 video games, the seedbed for an initial wish list of about 40 to be acquired in the near future, as well as for a new category of artworks in MoMA’s collection that we hope will grow in the future. This initial group, now installed for your delight in the Applied Design exhibition the Museum’s Philip Johnson Galleries, features Pac-Man (1980); Tetris (1984); Another World (1991); Myst (1993); SimCity 2000 (1994); Vib-Ribbon (1999); The Sims (2000); Katamari Damacy (2004); EVE Online (2003); Dwarf Fortress (2006); Portal (2007); flOw (2006); Passage (2008); and Canabalt (2009).

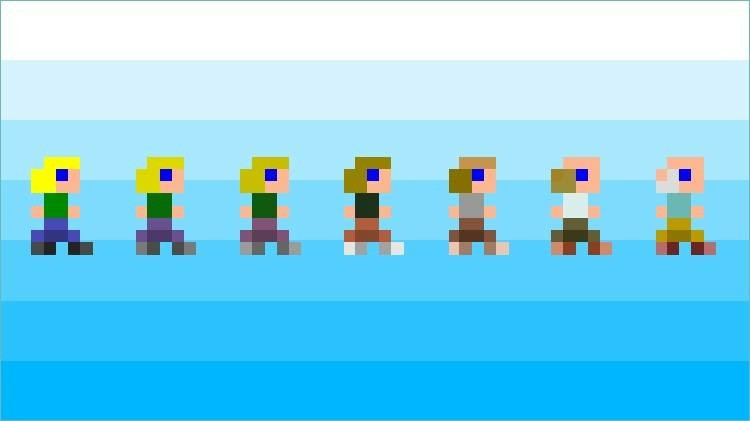

Alexey Pajitnov. Tetris. 1984

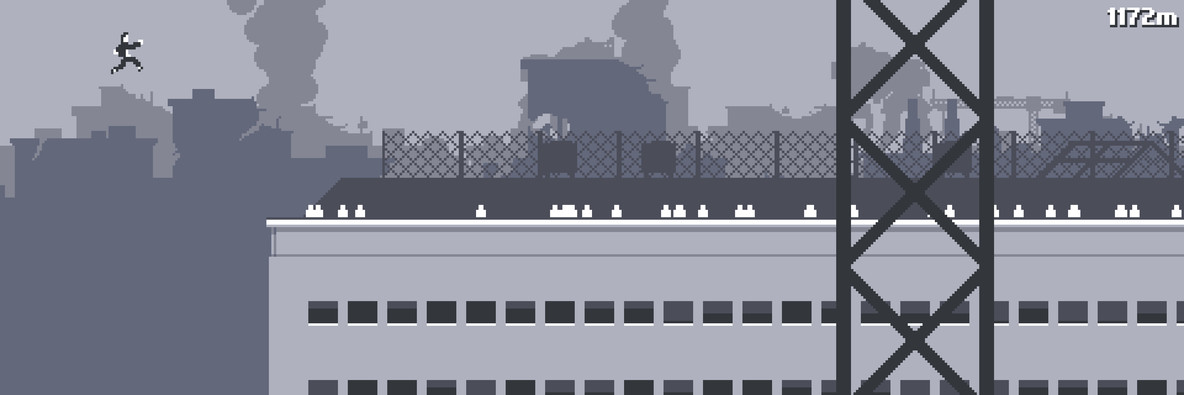

Adam Saltsman, Daniel Baranowsky. Canabalt. 2009

Over the next few years, we would like to complete this initial selection with Spacewar! (1962), an assortment of games for the Magnavox Odyssey console (1972), Pong (1972), Snake (originally designed in the 1970s; the Nokia phone version dates from 1997), Space Invaders (1978), Asteroids (1979), Zork (1979), Tempest (1981), Donkey Kong (1981), Yars’ Revenge (1982), M.U.L.E. (1983), Core War (1984), Marble Madness (1984), Super Mario Bros. (1985), The Legend of Zelda (1986), NetHack (1987), Street Fighter II (1991), Chrono Trigger (1995), Super Mario 64 (1996), Grim Fandango (1998), Animal Crossing (2001), and Minecraft (2011).

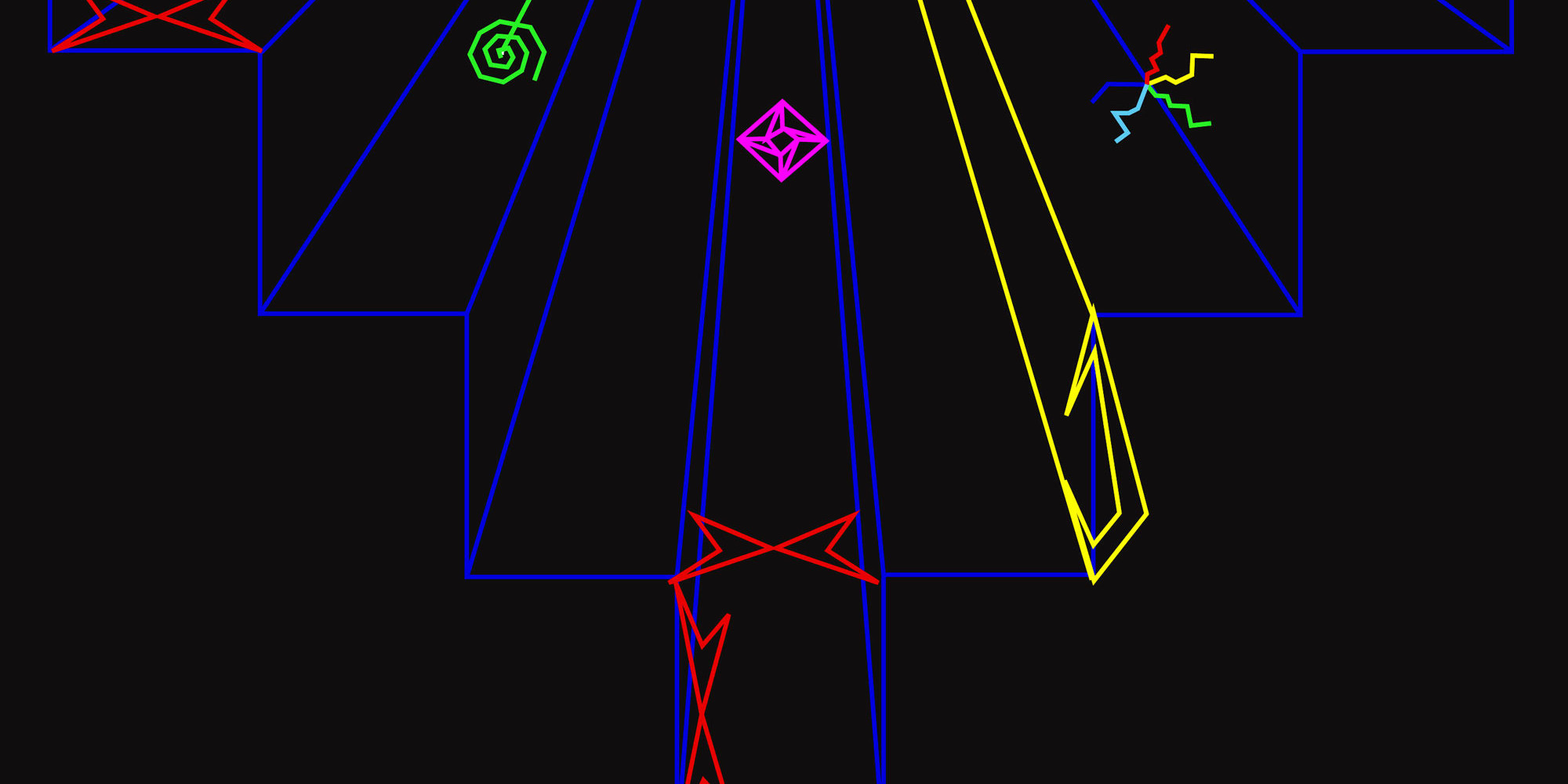

Valve. Portal. 2005–07

Are video games art? They sure are, but they are also design, and a design approach is what we chose for this new foray into this universe. The games are selected as outstanding examples of interaction design—a field that MoMA has already explored and collected extensively, and one of the most important and oft-discussed expressions of contemporary design creativity. Our criteria, therefore, emphasize not only the visual quality and aesthetic experience of each game, but also the many other aspects—from the elegance of the code to the design of the player’s behavior—that pertain to interaction design. In order to develop an even stronger curatorial stance, over the past year and a half we have sought the advice of scholars, digital conservation and legal experts, historians, and critics, all of whom helped us refine not only the criteria and the wish list, but also the issues of acquisition, display, and conservation of digital artifacts that are made even more complex by the games’ interactive nature. This acquisition allows the Museum to study, preserve, and exhibit video games as part of its Architecture and Design collection.

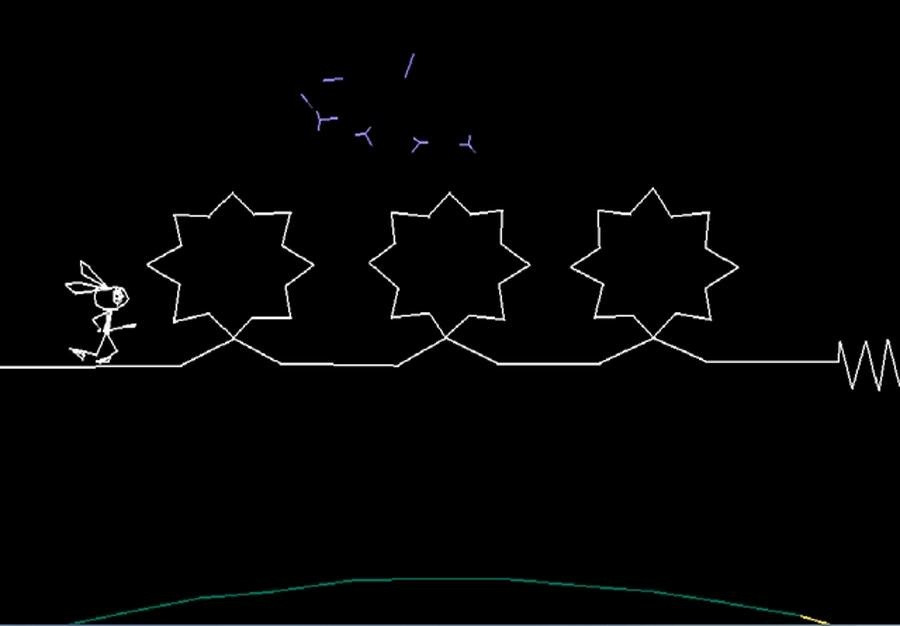

Masaya Matsuura. Vib-Ribbon. 1997–99

As with all other design objects in MoMA’s collection, from posters to chairs to cars to fonts, curators seek a combination of historical and cultural relevance, aesthetic expression, functional and structural soundness, innovative approaches to technology and behavior, and a successful synthesis of materials and techniques in achieving the goal set by the initial program. This is as true for a stool or a helicopter as it is for an interface or a video game, in which the programming language takes the place of the wood or plastics, and the quality of the interaction translates in the digital world what the synthesis of form and function represent in the physical one. Because of the tight filter we apply to any category of objects in MoMA’s collection, our selection does not include some immensely popular video games that might have seemed like no-brainers to video game historians. Among the central interaction design traits that we have privileged are:

Behavior

The scenarios, rules, stimuli, incentives, and narratives envisioned by the designers come alive in the behaviors they encourage and elicit from the players, whether individual or social. A purposefully designed video game can be used to train and educate, to induce emotions, to test new experiences, or to question the way things are and envision how they might be. Game controllers are extensions and enablers of behaviors, providing in some cases (i.e., Marble Madness) an uncanny level of tactility.

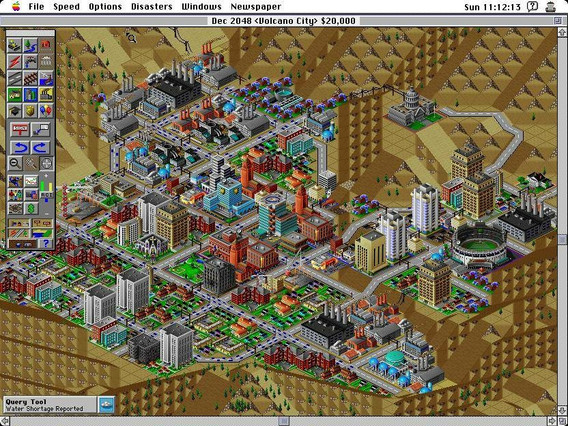

Will Wright. SimCity 2000. 1993

Aesthetics

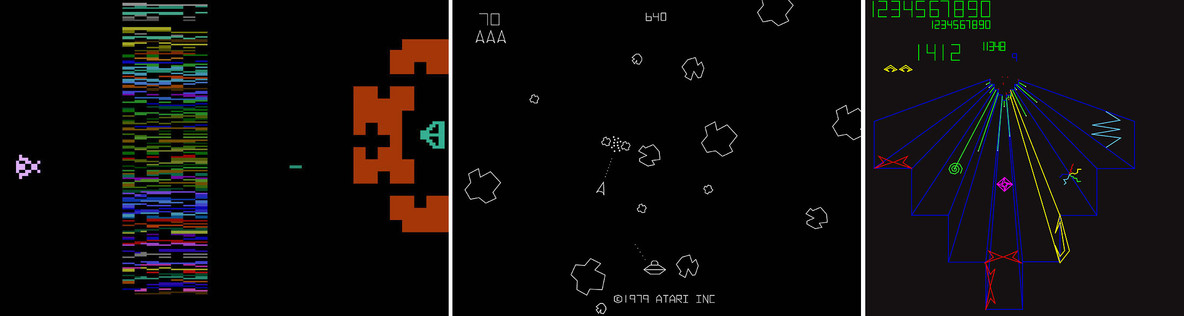

Visual intention is an important consideration, especially when it comes to the selection of design for an art museum collection. As in other forms of design, formal elegance has different manifestations that vary according to the technology available. The dry and pixilated grace of early games like M.U.L.E. and Tempest can thus be compared to the fluid seamlessness of flOw and Vib-Ribbon. Just like in the real world, particularly inventive and innovative designers have excelled at using technology’s limitations to enhance a game’s identity—for instance in Yars’ Revenge.

Jenova (Xinghan) Chen, Nick Clark. flOw. 2007

Space

The space in which the game exists and evolves—built with code rather than brick and mortar—is an architecture that is planned, designed, and constructed according to a precise program, sometimes pushing technology to its limits in order to create brand new degrees of expressive and spatial freedom. As in reality, this space can be occupied individually or in groups. Unlike physical constructs, however, video games can defy spatial logic and gravity, and provide brand new experiences like teleportation and ubiquity.

Time

How long is the experience? Is it a quick five minutes, as in Passage? Or will it entail several painstaking years of bliss, as in Dwarf Fortress? And whose time is it anyway, the real world’s or the game’s own, as in Animal Crossing? Interaction design is quintessentially dynamic, and the way in which the dimension of time is expressed and incorporated into the game—through linear or multi-level progressions, burning time crushing obstacles and seeking rewards and goals, or simply wasting it—is a crucial design choice.

Jason Rohrer. Passage. 2007

After which (games), came what—what is a museum to acquire? Working with MoMA’s digital conservation team on a protocol, we have determined that the first step is to obtain copies of the games’ original software format (e.g. cartridges or discs) and hardware (e.g. consoles or computers) whenever possible. In order to be able to preserve the games, we should always try to acquire the source code in the language in which it was written, so as to be able to translate it in the future, should the original technology become obsolete. This is not an easy feat, though many companies may already have emulations or other digital assets for both display and archival purposes, which we should also acquire. In addition, we request any corroborating technical documentation, and possibly an annotated report of the code by the original designer or programmer. Writing code is a creative and personal process. Interviewing the designers at the time of acquisition and asking for comments and notes on their work makes preservation and future emulation easier, and also helps with exhibition content and future research in this field.

Toru Iwatani. Pac-Man. 1980

Tarn Adams, Zach Adams. Dwarf Fortress. 2006

Of course, what we acquire depends on each game, how it is best represented, and how it will be shown in the galleries. If the duration of the game is short enough, the game itself could be made playable in its entirety. For instance, visitors were able to play Passage in its entirety in MoMA’s Talk to Me: Design and the Communication between People and Objects exhibition not only because it took a mere five minutes, but also because the narrative and message of the game required the player to engage with it for the full length.

For games that take longer to play, but still require interaction for full appreciation, an interactive demonstration, in which the game can be played for a limited amount of time, will be the answer. In concert with programmers and designers, we will devise a way to play a game for a limited time and enable visitors to experience the game firsthand, without frustrations.

With older games for which the original cartridges may be too fragile or hard to find, we will offer an interactive emulation—a programmer will translate the original code, which was designed for a specific platform, into new code that will create the same effect on a newer computer.

In other cases, when the game is too complex or too time consuming to be experienced as an interactive display in the galleries, we will create a video akin to a demo, in which the concept and characters of the game are laid out.

Finally, some of the games we have acquired (for instance, Dwarf Fortress and EVE Online) take years and millions of people to manifest fully. To convey their experience, we will work with players and designers to create guided tours of these alternate worlds, so the visitor can begin to appreciate the extent and possibilities of the complex gameplay.

Allan Alcorn. Pong. 1972

Video Games: Seven More Building Blocks in MoMA’s Collection

June 28, 2013

Quite a lot has happened since we announced the first 14 video games to enter the MoMA collection, seven months ago. MoMA Architecture and Design curator Paola Antonelli charmed Stephen Colbert, the exhibition Applied Design (featuring the games) opened to the public, and a heady debate raged regarding MoMA’s move into this field. (For more on this, watch Paola’s recent TED talk.) While all this was occurring, we continued the work of acquiring more games from our wish list.

From left: Howard Scott Warshaw. Yars’ Revenge. 1982; George “Ed” Logg, Lyle Rains. Asteroids. 1979; Dave Theurer. Tempest. 1981

Today, we are thrilled to announce the addition of one gaming console and six more video games to our collection. These include works from the early pioneers Atari, Taito, and Ralph Baer, and from the comparatively young Mojang. The new additions are the Magnavox Odyssey (1972); Pong (1972); Space Invaders (1978); Asteroids (1979); Tempest (1981); Yars’ Revenge (1982); and Minecraft (2011).

Ralph Baer. Magnavox Odyssey. 1972

Ralph Baer’s Magnavox Odyssey, the first home video game system and a masterpiece of engineering and industrial design, introduced electronic games to the American public. In the same year, a young and ambitious Nolan Bushnell founded Atari (where, by the way, an equally young and at least equally ambitious man named Steve Jobs first found employment). Atari rapidly became the most famous video game company in the world, and in an amazingly fertile period produced one seminal work after another. Concurrently, the already rich arcade culture of Japan was turned on its head with the release of Taito’s Space Invaders, a game that so captivated the Japanese public it led to a temporary nationwide shortage of 100-yen coins. When Space Invaders finally made it to the US, it conquered the arcade industry. The last work on our list is Mojang’s Minecraft, a fascinating game that combines multiple genres into one sprawling, unpredictable, and utterly addictive masterpiece.

Markus “Notch” Persson. Minecraft. 2011

It’s hard to overstate the importance of Ralph Baer’s place in the birth of the industry, as well as the significant roles Atari, Taito, and Mojang still play. The work of the designers of those early games became the building blocks of a new form of creative expression and design language; blocks upon which contemporary designers like Markus “Notch” Persson and his fellows at Mojang are building to make works that push the medium to wildly new, fascinating, and weird places.

In the infancy of this field a small number of visionaries laid the groundwork for where we are now: an industry of tremendous range and creative output. If I have learned anything in this process it’s that the early, seemingly simple games remain as vital and compelling today as they were when we played them in the cacophonous arcades or on the living room floors of our youth.

The team behind the 2012 acquisition stars MoMA Architecture and Design insiders Kate Carmody and Paul Galloway, but in preparing this research we have sought the advice of numerous people. We could not have done it without their contributions, and thank them wholeheartedly for their generosity, enthusiasm, and time. We will distinguish between RL (you know it, Real Life) and ML (MoMA Life). RL: Jamin Warren and Ryan Kuo of Kill Screen magazine; design philosopher and game author extraordinaire Kevin Slavin; and Chris Romero of the graduate program in museum studies at New York University. ML: Natalia Calvocoressi, Juliet Kinchin, Aidan O’Connor, and Mia Curran in Architecture and Design; in Graphics, Samuel Sherman; in Audio Visual, Aaron Louis, Mike Gibbons, Lucas Gonzalez, Aaron Harrow and Bjorn Quenemoen; in Information Technology, Matias Pacheco, Ryan Correira, and David Garfinkel; in Digital Media, Allegra Burnette, Shannon Darrough, David Hart, John Halderman, Spencer Kiser, and Dan Phiffer; in Conservation, Glenn Wharton and Peter Oleksik; in General Counsel, Henry Lanman; in Drawings, Christian Rattemeyer; at MoMA PS1, Peter Eleey; in Film, Rajendra Roy, Laurence Kardish, and Josh Siegel; in Media and Performance Art, Barbara London; and in Education, Calder Zwicky.

We also extend our great thanks to the game companies and designers who donated these important works to MoMA. Without their brave, forward-thinking participation, this project would not have been possible. A great thank you to Tarn Adams, CCP, Éric Chahi, Cyan Worlds, Electronic Arts, NAMCO BANDAI, NanaOn-Sha, Jason Rohrer, Adam Saltsman, Sony Computer Entertainment, The Tetris Company, thatgamecompany, Valve, and Will Wright.

Never Alone: Video Games and Other Interactive Design, organized by Paola Antonelli, Senior Curator, Paul Galloway, Collection Specialist, and Anna Burckhardt and Amanda Forment, Curatorial Assistants, Department of Architecture and Design, is on view at MoMA September 10, 2022–July 16, 2023.

Related articles

-

UNIQLO ArtSpeaks

Paul Galloway on the Volkswagen Beetle

An iconic automobile becomes a symbol of time and place, love and loss.

Aug 27, 2021

-

Resources

Are Museums the Research and Development Labs of Society?

Explore topics from AI to angels with this selection from MoMA’s R&D Salons.

Paola Antonelli, Theano Siaraferas

May 8, 2020