Seventeen Ways Art Inspired Us This Year

Our curatorial colleagues pick one moment of art that offered joy in 2021

Dec 28, 2021

As we approach the end of another difficult and momentous year, we reflect on the ways that, against all odds, creative expression still found a way to connect, inspire, and empower, sometimes in the most unexpected spaces. We invited our curatorial colleagues to share something in art and culture from 2021 that brought them joy or gave them hope. We hope these picks provide some creative spark for you, too.

Samantha Friedman

What could be more hopeful than a resurrection? The artist Rosemary Mayer—who died in 2014 after a too-long-under-the-radar career as a maker of fabric sculptures, sensitive drawings, and ephemeral performances—was, wonderfully, everywhere in 2021: in solo shows at the Gordon Robichaux Gallery and the Swiss Institute, and included in PS1’s Greater New York 2021. Her meditations on knot-tying had new resonance in a year when many of us were released from our habits and re-tethered to our intimates. And the “temporary monuments” she proposed seemed all the more prescient in light of once-permanent memorials being dismounted. The recognition is sadly belated, but she also reappeared at just the right time.

Samantha Friedman is an associate curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints.

Rosemary Mayer. Hipsipyle (detail). 1973. Installation view, Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching, Swiss Institute, September 9, 2021–January 9, 2022

Josh Siegel

Bruce Lee once observed that “patience is not passive—on the contrary it is concentrated strength.” As we continue to live in a twilight zone between home and the office, coming to terms with myriad existential pressures and uncertainties, I have taken refuge in reading books, watching movies, and listening to music in aspirationally completist fashion. It is something I’ve rarely had the time to attempt but have approached with great pleasure and humility: a chronological sweep through the films of Howard Hawks, from the 1926 marriage comedy Fig Leaves to the 1970 Western Rio Lobo (one of the great swan songs); the poems of Emily Dickinson; and, most recently, the novels and stories of Chester Himes and Iceberg Slim. Inspired by the recent Impulse! release of the breathtaking album John Coltrane: Live in Seattle, I’ve also been taking a trip through the jazz saxophonist and composer’s career from beginning to end, guided by Ben Ratliff’s study John Coltrane: The Story of a Sound and some terrific original liner notes.

Josh Siegel is a curator in the Department of Film.

Michelle Kuo

Pauline Curnier Jardin. Fat to Ashes. Exhibition view, Hamburger Bahnhof - Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin, 2021

The Rome- and Berlin-based artist Pauline Curnier Jardin created a towering, cream-and-pink foam structure in the cavernous hall of Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof museum. Resembling both a gleefully feminized coliseum and a monumental layer cake, the structure housed a small amphitheater. I sat inside and watched Jardin’s gorgeous and terrifying film of various public rituals, including a religious festival honoring St. Agatha and the Carnival of Cologne. The tumultuous scenes of congregation, procession, and destruction helped place our present moment in a context of human struggle and suspended belief. I left feeling unsettled—and somehow transformed.

Michelle Kuo is the Marlene Hess Curator of Painting and Sculpture.

Thomas / T. Jean Lax

Justin Vivian Bond and Anthony Roth Constanzo’s Only An Octave Apart. The collaboration between the cabaret commédienne and the operatic counter-tenor was a beautiful experiment in the duet form and its wild kinds of love.

Thomas J. / T. Jean Lax is a curator in the Department of Media and Performance.

Christophe Cherix

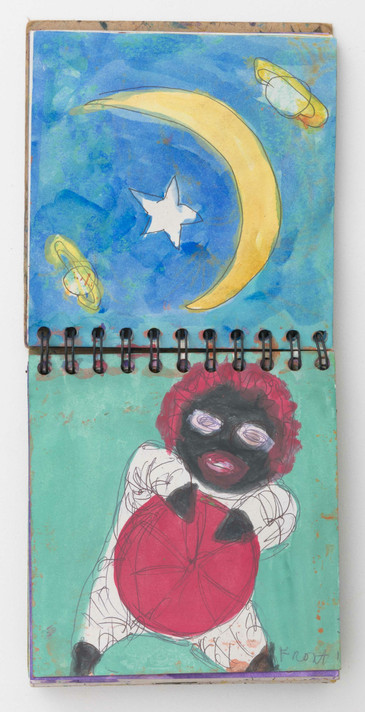

During my last visit, I found Betye Saar at work on a beautiful series of watercolors depicting Black dolls. The artist started collecting them during the 1960s—while visiting flea markets, or as gifts given by friends and family members—but had never devoted a body of work to them. These hard-to-find dolls, underrepresented among their kind for so long, are the newest bright stars in Saar’s magical cosmography.

Christophe Cherix is the Robert Lehman Foundation Chief Curator of Drawings and Prints.

Betye Saar. Page 64 and 65 from Sketchbook. 2020

Oluremi C. Onabanjo

Tiona Nekkia McClodden’s Conceptual Fade in Northeast Philadelphia, a 135-square-foot micro-gallery and library that contemplates conceptual practice across the African Diaspora through varied contexts and forms. Each exhibition offers an intimate study springing from a single work. The inaugural show took up the last acoustic bass of Jymie Merritt (1926–2020), a legendary jazz bassist and composer who was the founder of The Forerunners, a cooperative organization active in Philadelphia from the 1960s through the ’80s. The space is a palpable reminder of what it looks and feels like when artists thoughtfully witness the work of others, and insist on taking time to bring their visions into reality.

Oluremi C. Onabanjo is an associate curator in the Department of Photography.

La Frances Hui

Drive My Car. 2021. Japan. Directed by Ryûsuke Hamaguchi

In 2016, New Directors/New Films presented Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s Happy Hour, a mesmerizing observation of four women and their private struggles. The quietly transformative work, now in MoMA’s film collection, unfolds over more than five hours, steadily introducing new perspectives on the protagonists’ circumstances and on life itself. With not just one but two award-winning films released this year, both exploring the intricacies of the human heart—Drive My Car and Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy—the Japanese auteur has taken his craft to new heights. Few filmmakers capture the allure and ephemeral magic embedded in the passage of time like Hamaguchi. His singular, wizardly touch makes the most unassuming interactions and unsuspecting moments—often transpiring in nearly real time—infinitely enchanting. With unhurried and penetrating precision, Hamaguchi’s films register subtle shifts in insights and emotions, making him a master of intimate intrigue.

La Frances Hui is a curator in the Department of Film.

Roxana Marcoci

We live in revolutionary times—times of love, times of reckoning. Or, perhaps, this moment is about the unmaking and remaking of history. I had this path-changing feeling throughout 2021 while working with my colleague Thomas / T. Jean Lax and artists Deana Lawson, Dalton Paula, Cameron Rowland, Tourmaline, and Kandis Williams on Critical Fabulations, an installation that takes its title from Saidiya Hartman’s essay “Venus in Two Acts.” First published in 2008 in Small Axe, a Caribbean journal of criticism, in an issue on the archaeologies of Black memory, the essay bridges fact and speculative fiction to fill in the silences of historical archives. In conversations with Hartman, and in collaboration with the artist-run publishing imprint Cassandra Press, for this occasion we republished the text as a zine. Our shared labor was an active process of working through the historical context of Black resplendence, grit, struggle, and transcendence as a creative force of affirmation.

Roxana Marcoci is a senior curator in the Department of Photography.

Anne Umland

It was wonderful to see Meret Oppenheim’s fabulous, greenery-clad Fountain (1983) in Bern in October, looking particularly verdant and thriving on the occasion of her transatlantic retrospective Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition, just down the street at the Kunstmuseum Bern (open through February 13, 2022).

Anne Umland is the Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller Senior Curator of Painting & Sculpture.

Meret Oppenheim. Fountain. 1983. Waisenhausplatz, City of Bern, Switzerland

Lucy Gallun

This year I am reflecting on the remarkable histories and contributions of nonprofit community organizations in our city, such as the American Indian Community House (AICH). In August, on the occasion of Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill’s Projects exhibition, AICH co-hosted An Artist Panel on Gifting. On view right now in Gallery 213 at MoMA, Sky Hopinka’s beautiful film I’ll Remember You as You Were, not as What You’ll Become incorporates footage of poet Diane Burns performing at the AICH in 1998. And a room of paper-bag drawings and wall-hangings by G. Peter Jemison, an artist and former curator and director of the AICH Gallery, is included in Greater New York 2021 at MoMA PS1 (on view through April 18, 2022). I am grateful to experience this constellation of extraordinary work from years past and present.

Lucy Gallun is an associate curator in the Department of Photography.

Dana Ostrander

Pamela Council. A Fountain for Survivors. Installation view, October 14–December 8, 2021

While waiting in Times Square to enter Pamela Council’s A Fountain for Survivors, I watched as Minnie Mouse wandered over and touched one of the 400,000 acrylic fingernails that made up the fountain’s armored shell. Like everyone else, she seemed drawn into its orbit. Inside the structure, street noises were muffled, replaced by the gentle fizz and trickle of water from a fountain. To design this soothing space, Council took inspiration from Black self-care routines—incorporating the softness of a childhood bedroom, the protection of acrylic nails, and the purifying fragrance of Florida Water (used in Voodoo and Santeria practices). Council’s fountain for survivors tacitly acknowledges the struggles New Yorkers have experienced over the past two years, and the disproportionate toll on communities of color. But as we all return to public life, it is also a hopeful reminder to sustain the care practices developed during moments of privacy and reflection.

Dana Ostrander is a curatorial assistant in the Department of Photography.

Paola Antonelli

Telfar Clemens whipped up the uniforms for the Liberian Olympic Team in his Brooklyn atelier, using his own fabrics and designing layers and components with competition performance and award ceremony gravitas in mind. With those uniforms, he leaped across sports, genders, and geopolitics to make his parents’ country the epitome of style, strength, and hope, with a branding intensity that stands as a glowing paragon of soft-power diplomacy. I have always admired Telfar’s and his partner Babak Radboy’s determination to use their life and work to represent and transform, and I could easily ink Telfar’s motto—“Not for you—for everyone”—on my neck. The Bushwick Birkin, the genderless collections, and Telfar.tv are awesome milestones in the history of fashion. Yet when I first saw the video with which Telfar announced his collaboration with the Liberian team, I was bowled over. Olympian rather than Olympic, the team of three projected an image of a country of geniuses, champions, and gods.

Paola Antonelli is a senior curator in the Department of Architecture and Design, and MoMA’s director of Research and Development.

Martha Joseph

Madeline Hollander. Review. 2021. Performa Commission for the Performa 2021 Biennial

In 2021, amid vaccine development and the continued closure of indoor venues, artists performed outside. Organizations like Performa in New York and Jacob’s Pillow in Massachusetts fully embraced the possibility of outdoor performance. As a result, audiences had the opportunity to experience dance, music, and performance art again in safe conditions. This was not always comfortable for artists or audiences. But I was struck by the beauty, tension, and tenderness of encountering performance in unexpected spaces: a crowded Lower East Side intersection, an empty public pool on a cold autumn night, a secluded fire pond on a mountain in the woods.

Martha Joseph is the Phyllis Ann and Walter Borten Assistant Curator of Media and Performance.

Diane Burns. Poetry Spots: Diane Burns reads “Alphabet City Serenade”. 1989

Lanka Tattersall

In a year that brought daily news about shifting language and wrenching data, poetry has been a friend. Sometimes I can’t get the cadence of the late poet Diane Burns’s voice reciting her “Alphabet City Serenade” (1989) out of my head. I first encountered it in a video of her performing the poem that’s currently included in Greater New York 2021, on view at MoMA PS1. Burns intones, I’m American royalty/walking around with a hole in my knee/I’m a hopeful aborigine/trying to find a place to be. Her cool eloquence and wise attitude give me a lift, and remind me to keep a long view of history.

Lanka Tattersall is a curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints.

Esther Adler

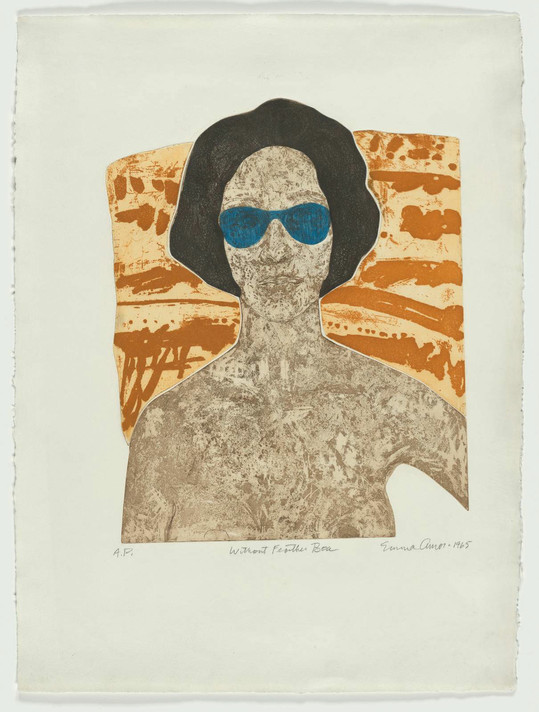

My friend Ana Torok and I took a day trip to Philadelphia to see a number of exhibitions—it’s always lovely to look at art together, and we got to use the time on the train to recap reality TV storylines. One of my favorite things we saw that day was the Emma Amos retrospective, on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through January 17, and one of my favorite pieces in that show is this incredible print, Without Feather Boa. MoMA just acquired our own copy of this etching, and it is an inspiration for how I want to exist in this world—fearless and ready to face anything. Maybe wearing a sweater though.

Esther Adler is a curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints.

Emma Amos. Without Feather Boa. 1965

Smooth Nzewi

It was a strange experience walking through Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration at MoMA PS1 last January with the devastating COVID-19 pandemic as an unsettling backdrop. Nonetheless, the audacious exhibition offered a moment of profound clarity about the systemic impact of the US prison industrial complex on regulating the freedom of Black and Brown bodies. But even more meaningful is the lesson it taught us about how conditions of incarceration or restricted mobility can inspire the escape hatch of the imagination, offering a space for creativity to emerge and re-energize our cultural experience.

Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi is the Steven and Lisa Tananbaum Curator in the Department of Painting and Sculpture.

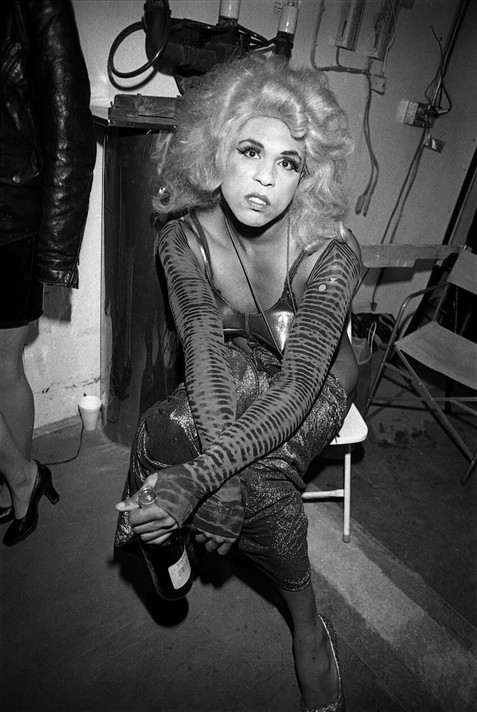

Reynaldo Rivera. Vaginal Davis, Downtown. 1993

Stuart Comer

Last January, while galleries and museums in Los Angeles remained shuttered during a particularly challenging moment in the pandemic, a friend handed me a copy of a book whose existence came as a joyous surprise: Reynaldo Rivera: Provisional Notes for a Disappeared City. Published by Semiotext(e) at the end of 2020, and edited by Hedi El Kholti and Lauren Mackler, the book gathers roughly 200 photographs shot by Rivera during the 1980s and ’90s. His work chronicles a queer Latinx bohemia in Los Angeles whose creative intensity continues to burn bright in Rivera’s images, even as the vibrant community he documented has been dispersed into a very different formation in the 21st century. This book insists on remembering a moment that has been largely ignored by official accounts of the period. To quote Rivera, “To find things about Latinos, you have to read other people’s footnotes,” he says. “I wanted a book about us in L.A. where we are not the footnote.”

Stuart Comer is the Lonti Ebers Chief Curator of Media and Performance.