Deep Learning: AI, Art History, and the Museum

Refik Anadol’s Unsupervised invites us to come to terms with new ways of making history at the edge of what’s technically possible.

Joan Kee, Michelle Kuo

Jun 15, 2023

On the occasion of Refik Anadol’s installation Unsupervised, currently on view in the Agnes Gund Lobby of The Museum of Modern Art, curator Michelle Kuo and Ford scholar-in-residence and art historian Joan Kee contemplate the new spaces of perception and creativity it opens up for the audience and for the machine.

Joan Kee: One of the first things you notice about Unsupervised is how closely and intensely people look at the works. I understand that, normally, the average museumgoer spends about 30 seconds in front of an artwork before they move on to the next one. I’ve seen people in front of Unsupervised for hours. Equally compelling are the debates Unsupervised provokes over the nature of viewing. Do we see it in the way we might Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night, one of the museum’s most popular works, or is it that the work engulfs the viewer a bit like [Henri] Matisse’s Red Studio, so that it becomes a struggle to see outside its physical boundaries?

Michelle Kuo: That makes a strange kind of sense—there’s something about the near-abstraction of Matisse’s work, the way it tips over into a sea of red—that I see in Unsupervised. Both works are deeply rooted in the circumstances of their making, and respond to histories of artistic form, but have very little legible reference to social context, or a message, or historical events. Neither work can be decoded or rationally explained and understood the way the more traditional art of their contemporaries can.

Part of the reason Unsupervised holds you, draws you into close looking over time, is because it is based on an adaptive system. Adaptive systems are constantly changing, in response to their environment and to prior events, and to experience them in all their complexity, you often need to experience them through your body, over time. 1 With Unsupervised, you’re watching a complex system unfold, unpredictably, and without traditional narrative structure like a beginning, middle, and end. It’s not like most other digital artworks; this is not code that straightforwardly turns an input into an output, or follows a preset system. (It's also very hard to photograph!)

Anadol created a custom machine-learning model, based on multiple open-source frameworks and custom-rendering programs, to learn about MoMA’s collection—the information about the artworks in our archive, all the artworks, artists, dates, mediums, materials, visual qualities—and then try to sort the information, to classify these hundreds of thousands of data points into patterns or clusters of relationships. But what the machine learning model, in tandem with Anadol’s studio, decides what and how to classify, is in part a black box. It may decide that certain things are relevant, or similar, in ways that we just wouldn’t understand. It builds a very complex map of all its learnings, architecting a kind of galaxy of the collection, clustering “stars” or artworks that it thinks belong together, and then—and this is the astonishing part, to me—essentially flies around that galaxy. And in between all the clusters of information, in between the existing artworks in the history of MoMA’s archive, there is empty space. And the machine learning model looks at that empty space and says, “Nothing exists here. But what could exist? What might exist?” So what you are seeing in the main work in Unsupervised is its continuous creation of what could exist, but doesn’t, in the archive. Unsupervised is creating novel art-historical trajectories and forms in this wild, nonlinear way. It is looking at the holes of history.

I think this is why many people seem to experience a kind of wonder in front of the work—there’s something unfathomable that seems to be unfolding, but Anadol makes its complexity somehow perceptible to us humans. It is more like watching an ecosystem, with infinite duration.

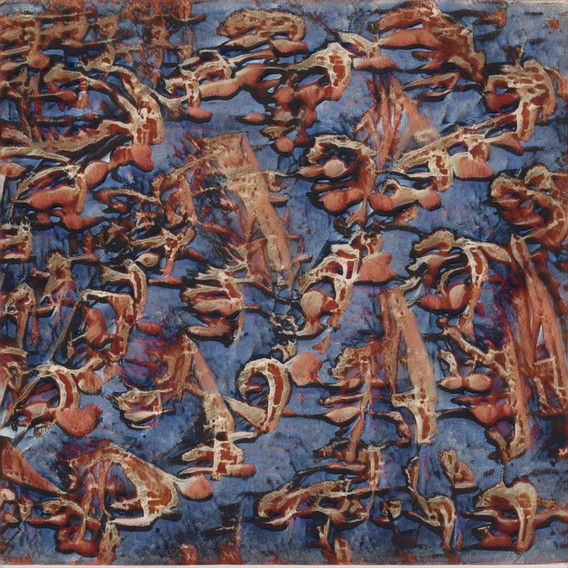

Sample data visualization of Unsupervised

Art is a particularly effective way of illuminating the role feelings play in considering the politics of technology.

Joan Kee

Installation view of Unsupervised

Abstract art and machine learning have both confounded the desire to read art as a human-made symbol or expression.

Michelle Kuo

JK: The viscerality of reactions to Unsupervised emphasizes how art is a particularly effective way of illuminating the role feelings play in considering the politics of technology. I see the work as a particularly insistent call for viewers to approach AI pragmatically, to defend against its more intrusive effects. At the same time, computers don’t see as humans do. And it is precisely why they will open up new possibilities of human-initiated creation.

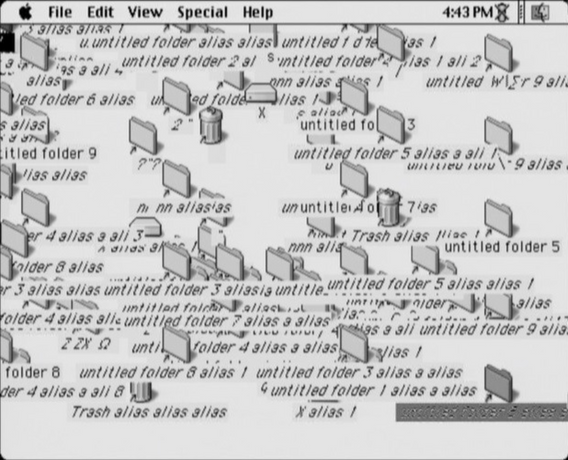

Unsupervised positions machine learning as an extension of process-based art, so that it becomes possible to see humans and machines as distinct without requiring them to perform as each other’s adversary. It summons other histories of art “born” in the digital sphere, such as net.art, where works like My%Desktop (2002), by JODI, involve taking the source code of a website as its material. But I’m wondering if Unsupervised is trying to push that even further by questioning how we come to terms with a way of making work that itself has not yet been resolved, and itself is changing very quickly.

MK: New technologies are often met with fear or outright rejection—and, of course, with good reason. But I think it’s just as critical to grapple with them, to even try to change them, or misuse or repurpose them, or adapt them for artistic ends. There’s always been this caricature of art that involves technology as being, as you say, either technophilic or technophobic, utopian or dystopian. One is supposedly naive, the other critical. Some artists simply try to reject technology (even as they use computers, or cars!), while others use their art practice to critique technology, often in crucial and devastating ways—which has led to brilliant artworks. But then there are artists who, at least since the postwar period, decided that actually, there’s so much happening at the bleeding edge of technology that if we don’t understand the technology itself, and if we don’t actually get in there and try to experiment with it, modify it, or have some agency in the shape that it takes, then we are just giving up. Otherwise we’re abdicating control to corporations, universities, governments, etc. And that is where I think an almost activist stance comes in some of these practices. Trying to turn the tables, and actually alter the ways in which technology is being used, or what technologies are developed in the first place.

We often want artworks to wear their criticism on their sleeve, or to be very literally about human emotion or “meaning”—when Unsupervised asks the very question: What happens beyond human emotion or critique or meaning? The work actually poses questions—not answers—about “symbolic value” and “meaning.” Symbolic to who, or what? This is one thing that abstract art and machine learning share: they have both confounded the desire to read art as a human-made symbol or expression.

JODI, Joan Heemskerk, Dirk Paesmans. My%Desktop. 2002

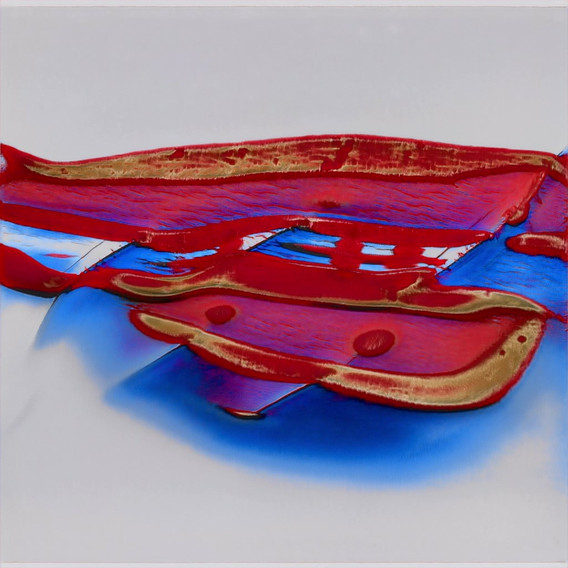

Helen Frankenthaler. Jacob’s Ladder. 1957

JK: The narrative about machine learning is being spun as a human-versus-AI contest of unprocessed feelings that can’t help but efface some of the complexity of the technology involved, or what in fact needs to be regulated. Anadol’s work compels other narratives, including what exactly constitutes human intervention. And does the machine itself have some claim to electronic personhood, as has been debated in the European Parliament?

One way to think about it is to ask if machines deserve human sympathy. I always think that the predictive model of AI is a little bit sad. You know, these machines that are trained to process these commands over and over again. There’s a little bit of pathos about that as well.

MK: There are many different types of deep learning—and now, specifically, very new types of generative AI—and they keep changing our understanding of categories like human agency, thought, and emotion, and non-human systems of agency, thought, and even something like emotion, which at the end of the day is a chemical and neurological phenomenon in humans; artificial neural networks are modeled on the neurons in a human brain. Unsupervised reflects on “real” versus “artificial” creation. It questions the dividing line between human and machine agency or creativity in the first place; it questions what composition—artistic choice or gesture—is. And yet these are issues that already came to a head in postwar abstract art.

JK: Yes, I think the history of abstract painting actually provides another way of thinking beyond traditional models of human agency. Because abstract artists have long embraced mark-making that’s not readily traceable to human gestures. Think of the chance drips of paint of a Jackson Pollock, or how Helen Frankenthaler allowed diluted paint to soak into unprimed canvas at its own pace. Unsupervised asks its audiences to consider abstraction and its histories as structures whose capacity for production is not exclusively governed by human intention. Sometimes the work resembles a sequential unfurling of petal-like shapes, not unlike what happens in Georgia O’Keeffe’s Abstraction Blue (1927). At other times, rounded biomorphic shapes will sort themselves into sections, then dissolve into granular, bead-like units in a manner that suggests the movement of water. What look fleetingly like runaway parts from a Jean Arp reassemble into components that might pass for a Jorge Pardo daydream in embryo, for example.

Unsupervised amplifies a deep tension in the history of abstract painting: between the strategy of allover painting, in which each part of a composition bounded by a frame is treated equally, and a model of excess or abandon, in which marks push beyond the frame that supposedly delimits the beginning or end of a work. In Unsupervised, the four edges of the screen on which the labor of the machine appears often read as sides of a box, or as edges of a three-dimensional frame. Sometimes those edges work as boundaries just able to contain the unruliness of forms covering a large surface area. But, just as frequently, you’ll see those forms spill over the sides. The spillage doesn’t look particularly intentional, but it’s not completely random either. That intermediate zone between artful intention and the absence of method is a core dynamic in histories of abstraction.

MK: Some of that plays out, of course, in the very unique and peculiar archive that the work is responding to: the collection of The Museum of Modern Art. So when Unsupervised responds to that art historical archive, which is often centered around histories of abstraction, it is responding to entire histories of artists already questioning what abstract art might mean, or even how to remove one’s own human subjectivity from the act of art making. Many artists were afraid of arbitrariness, and so they looked for ways to use outside systems or rules—random number generators, early computers, or simply chance—to determine the form of their work. How not to compose. You have kinetic art, from Jean Tinguely’s semi-automatic “drawing machines,” to David Medalla’s unspooling foam bubbles, to the psychedelic fever dream of expanded cinema and “visual music,” and the abstract computer films of Lillian Schwartz. Most of these were dismissed in their time as kitsch or spectacle, but I think they form an alternate strain of modernism that is actually as important as echt-modernist histories of progress.

What sort of other humannesses can actually be possible because of AI, not in spite of it?

Joan Kee

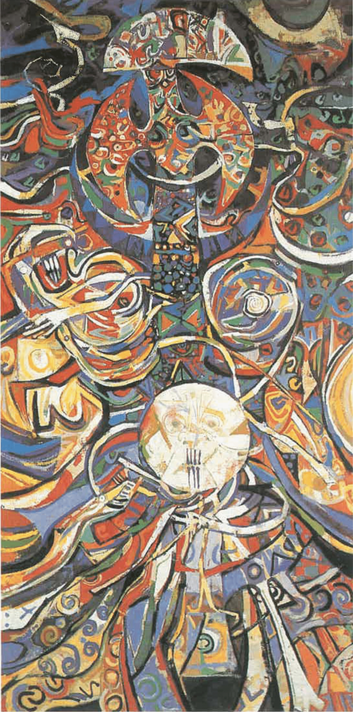

JK: Unsupervised also strikes me as an abstraction in the software-engineering sense of the word, where the simplicity of the interface conceals the complexity of different histories of art. To some, the work may deceptively look like something we’ve encountered before, be it an LED light show or LSD-induced hallucination. But the work’s unconscious—if a machine can be said to have an unconscious—turns on another history of abstraction that sometimes gets overwritten by modernist style categories like Abstract Expressionism, Surrealism, Fauvism, and the like. I’m thinking of works like Alexander (Skunder) Boghossian’s Computer Automatic Electronic Machine for Calculating, which, to my mind, haunts the unconscious of Unsupervised: this was a monumental enmeshment of color, line, light and pattern by the Ethiopian-American artist who, incidentally, was the first African artist to have work in MoMA’s collection. Even though it’s from 1978, the very large scale of Boghossian’s painting, which measures over eight feet by three feet, and its refusal to stay still—with forms jostling, overlapping, and pulsing—is very much in concert with how Unsupervised unfolds. Boghossian may have only been dreaming of an electronic machine for calculating wonder, but he could have been speaking about Unsupervised when he said that an artist was someone who could be influenced by an image and draw from it—but never duplicate it exactly.

There are other ghosts in the machine, too, like Harry Smith’s Early Abstractions—short animated films made between 1946 and 1957 that were created by manually painting, dyeing, bleaching, and stamping 35mm film. They appear to be in a constant state of flux, of abstract forms coming together and apart. Or think of Thomas Wilfred’s Lumia Suite, Opus No. 158, which was commissioned by MoMA in 1963 and appeared to be dreaming of Unsupervised before it was a twinkle in Anadol’s eye. It was on continuous view at MoMA for nearly 20 years, and a perennial favorite—[former director] Alfred Barr Jr. once said the museum received more inquiries about this work than any other in the collection!—that invited viewers to sit before a giant screen showing compositions made of reflected light that slowly changed color, shape, and orientation. Wilfred likened the device controlling the various mechanical and electronic parts to a symphony conductor, not unlike how Anadol regards AI as a collaborator.

Unsupervised makes a case for thinking about formalism as an antidote: not as something “empty,” but as a rejoinder to the old idea that artworks are really only encryptions needing to be solved. That misunderstanding is alive and well today, as seen by how frequently Unsupervised is “explained” through appeals to physical similitude to something familiar. But the work deflects this kind of literal reference, by being constantly and sometimes maddeningly elusive—alluding to any number of possible referents without committing to any of them. Like so many abstract works, Unsupervised steadily refuses to answer the question “What is it about?”—which can provoke fear, even hostility, in some. But to not take Unsupervised seriously, to not afford it an opportunity to be considered on its own terms, is to effectively discount entire histories of form.

At the same time, I see Unsupervised as part of a longstanding push-pull dynamic, in which some artists explore advanced tech, even changing it or developing their own inventions, while others deliberately embrace the very low tech or outmoded.

Skunder Boghossian. Computer Automatic Electronic Machine for Calculating. 1978

Thomas Wilfred. Lumia Suite, Op. 158. 1963

MK: What’s interesting is that in Anadol’s work, older and newer technologies come together in a kind of collage. He customizes a GAN, which is not even the most “advanced” type of generative AI now, and combines it with different types of rendering software and new mapping algorithms. And he does this in order to play with the degree of efficacy of these different algorithms: to explore different degrees of human intervention and control and different degrees of letting go, letting the machine conjure its own interpretations of the archive and of human memory.

The title of Unsupervised is very specific: it refers to a technical term for a type of machine learning that Anadol and his studio use. Most machine learning is “supervised learning,” where the AI needs to try to classify the information that is before it. (Even that is still difficult: We have autonomous cars, but they still can’t distinguish between the moon and a stop sign.) In supervised learning, humans tag images, for example, or bits of information, in order to train a machine learning model. So, I would go through the data set, and I would tag an image of a pen with the word pen.

Unsupervised learning, on the other hand, is where the machine does the tagging itself. It’s a whole other kind of black box where the machine is actually deciding not only how to tag something, what kinds of properties something should be classified as possessing, but it’s also deciding in many ways what is meaningful, what is of value, in terms of information. This is already opening up a kind of agency on the part of the machine that is very different from traditional processes of supervised learning.

Anadol is using unsupervised learning so that the work can actually generate something new based on its learnings, rather than just classify and process. And then the artist is in his studio working with this model, almost like an electronic musician with lots of different dials in front of him, adjusting what kinds of learning takes place, the rate at which the learning takes place, thousands and thousands of parameters around what kind of forms it could generate.

But at the same time, there’s a huge gulf between that stage and getting to the point of creating something that looks the way the works in Unsupervised do. There’s so much intervention and, in fact, human collaboration. Because with machine learning, you often might get noise. It doesn’t necessarily generate anything that we find meaningful or that we actually could perceive. And so, Anadol is working in concert with this quasi-organic, changing, adaptive system—but also guiding it away from what it might normally optimize, or “think,” to produce a series of morphologies that is unpredictable but neither simply a chance occurrence, nor fully automated. There’s an interplay between probability and indeterminacy.

And then, layered on top of that, in two of the works, is a diagram, a visualization, of the AI’s movements in space, moving throughout that complex map or galaxy it has constructed based on everything it’s learned, and classified, and clustered according to patterns of affinities. Again, these are affinities that we may never even perceive or think of, building a very complex map—in this case, literally 1,024 dimensions. This is not perceivable by human eyes. But what Anadol is doing is creating a map of movement that we can perceive, either as a network of shifting, connected lines, or as four-dimensional fluid dynamics, which looks like a rushing waterfall. It’s almost as if you’re watching a dance unfold in real time, but the choreographic score is being overlaid on top of the dance.

Installation view of Refik Anadol: Unsupervised

These technologies are already all around us—so we should try to understand them if we are to confront them, or critique them, or actually change them.

Michelle Kuo

MK: I think this goes back to the 20th-century discussion of deskilling, or deliberately removing technical mastery from making art. The entire question of technical facility in art versus the role of human agency in deeming something or defining something as art is taken to a whole different level here. All these debates around what constitutes human or artistic subjectivity, and artists who are attempting to take the subject out of the procedure or process of art making—Unsupervised poses yet another twist. Some of those artists were trying to take human choice, or subjectivity, out of art-making because, for example, they wanted to critique the notion of subjectivity as a Western bourgeois rationalist project, a human “civilization” that, let’s face it, led to catastrophes on the scale of world war. That’s one historical moment.

This is another historical moment in which, as you’re rightly pointing out, artists may be questioning their subjectivity again; and subjective creation, experience, and perception are being radically transformed as we speak.

JK: What role do you envision museums playing in shaping some of the public debates on AI? This is an exciting moment for art, and museums, to lead discussion regarding AI itself in ways that could potentially enrich law and policymaking on a broad scale.

MK: I think museums play a role in reexamining archives, in supporting artists’ experimentation, and in creating new kinds of perceptual and sensory experiences. And insofar as that kind of perceptual experience leads to new ways of understanding, or sensing, the activities of complex systems like deep learning or machine intelligence, then that may have ripple effects and actually change our understanding of the ontology of these technologies themselves.

And Unsupervised is a special case because it is so bleeding edge, challenging those technologies and pushing them to do things they weren’t made to do. What’s happening in the works’ process is such an intricate dance of artist and machine, of control and letting go, of human will and machine will. And I think that dynamic leads to interesting insights about what AI can and cannot do, what it should and should not do. And that, of course, may have implications for public policy. These technologies are already all around us—so we should try to understand them if we are to confront them, or critique them, or actually change them.

Sample data visualization of Unsupervised

Refik Anadol: Unsupervised is on view through summer 2023.

Related articles

-

Refik Anadol on AI, Algorithms, and the Machine as Witness

The artist behind an epic installation at MoMA answers seven questions about the new realms explored in his data-driven work.

Refik Anadol

Dec 20, 2022

-

Modern Dream: How Refik Anadol Is Using Machine Learning and NFTs to Interpret MoMA’s Collection

From DeepDream to the metaverse, a group of artists and curators sat down to discuss new ways of creating, sharing, and communicating about art.

Refik Anadol, Casey Reas, Michelle Kuo, Paola Antonelli

Nov 15, 2021