Lincoln Kirstein, Man of Letterheads

Associate curator Samantha Friedman traces Lincoln Kirstein’s distinguished career as a builder of institutions, using his correspondence as a guide.

Samantha Friedman

May 13, 2019

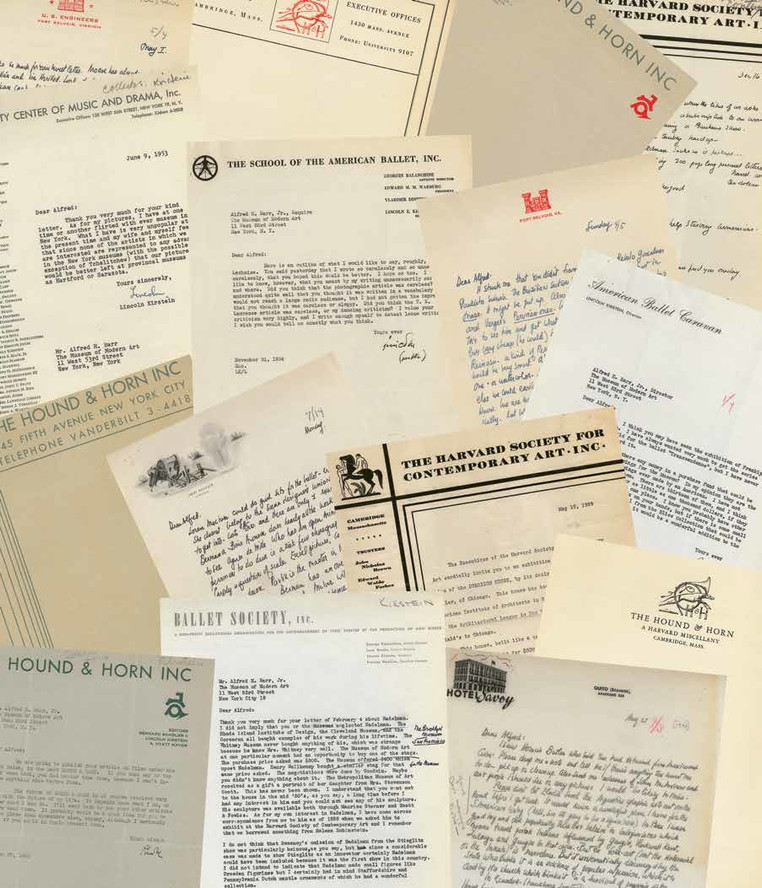

Collage of letterheads, designed by Inventory Form & Content (IN-FO.CO) as the endpaper to the exhibition catalogue for Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern

“I cant [sic] resist this beautiful stationary [sic],” Lincoln Kirstein typed, by way of opening a 1943 message to MoMA’s founding director Alfred H. Barr Jr. on letterhead issued by a special service office of Ft. Belvoir, Virginia, where he was stationed during World War II. That stationery he found, but others he commissioned for the many enterprises—magazines, societies, dance schools, and companies—he founded or cofounded. As prolific an institution-builder as he was a correspondent, the letterheads on which Kirstein dropped lines tell as rich a story about this man of many pursuits as their contents. On the occasion of the exhibition Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern, here are a dozen epistolary designs from MoMA’s Archives that, considered together, convey the arc of Kirstein’s contributions to American culture.

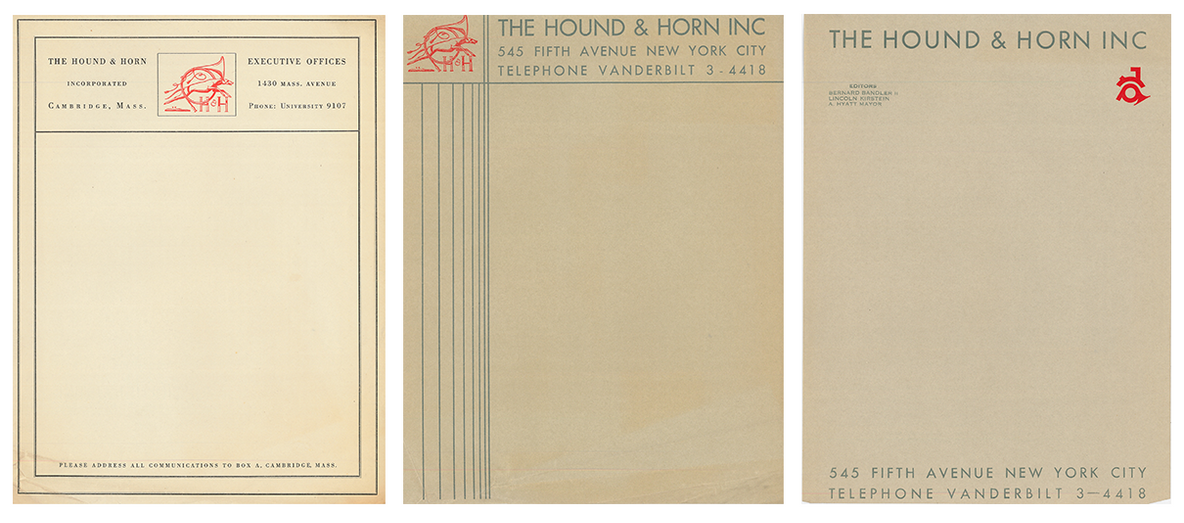

Three generations of Hound & Horn letterhead. The Hound & Horn Scrapbook. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

Kirstein’s innate talent for building institutions was revealed early. As a Harvard sophomore, he cofounded, with Varian Fry, the journal Hound & Horn. He invited eminent poets like Ezra Pound and Marianne Moore to contribute to what was essentially his college literary magazine—and they said yes—partly because Kirstein understood, already, the legitimizing power of a strong graphic identity. The three generations of letterhead shown here (the first and second featuring a logo by Rockwell Kent) show the hound and horn of the journal’s title morphing from an elegant, interlaced insignia into a bold, abstracted icon, as the magazine’s headquarters also shifts from college in Cambridge to the big time in New York.

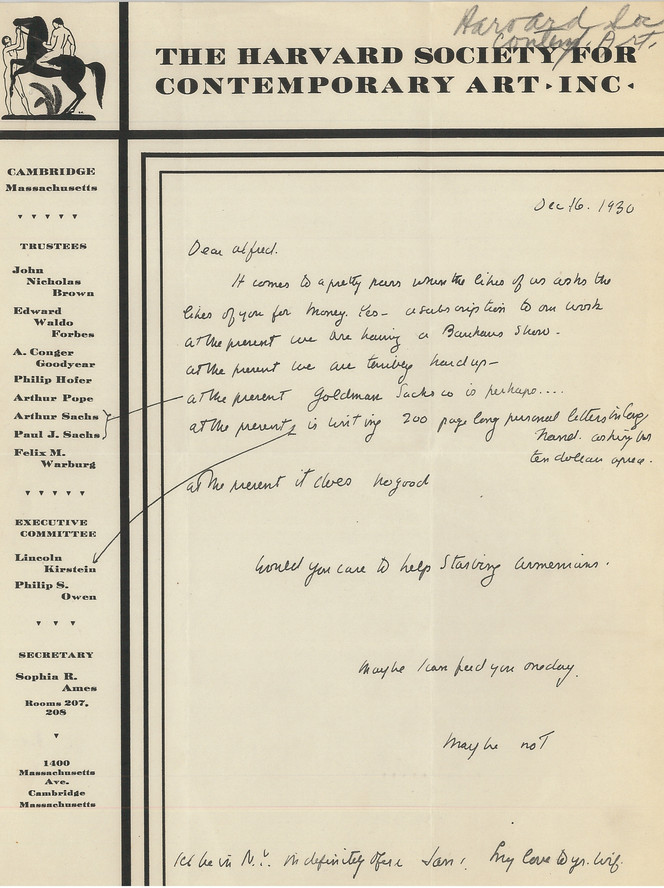

Letter from Lincoln Kirstein to Alfred H. Barr Jr. requesting funding for The Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, Inc., December 16, 1930. Alfred H. Barr Jr. Papers, I.A.3. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

Now a Harvard junior, Kirstein expanded his extracurricular pursuits to cofounding the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art with classmates Eddie Warburg and John Walker III. With no forum in Boston for showing art of the moment, Kirstein organized exhibitions in two rooms of the Harvard Cooperative building, securing impressive loans on innovative topics—everything from the Bauhaus to Buckminster Fuller to Ben Shahn—thanks in part to the professionalism of his materials. In this handwritten fundraising plea to Alfred Barr, he draws arrows to several of the names listed on the organizational masthead—including their advisor Paul J. Sachs and his brother Arthur, both scions of the Goldman Sachs dynasty, and referencing his own name as the desperate campaigner writing pleas for donations to the fledgling society.

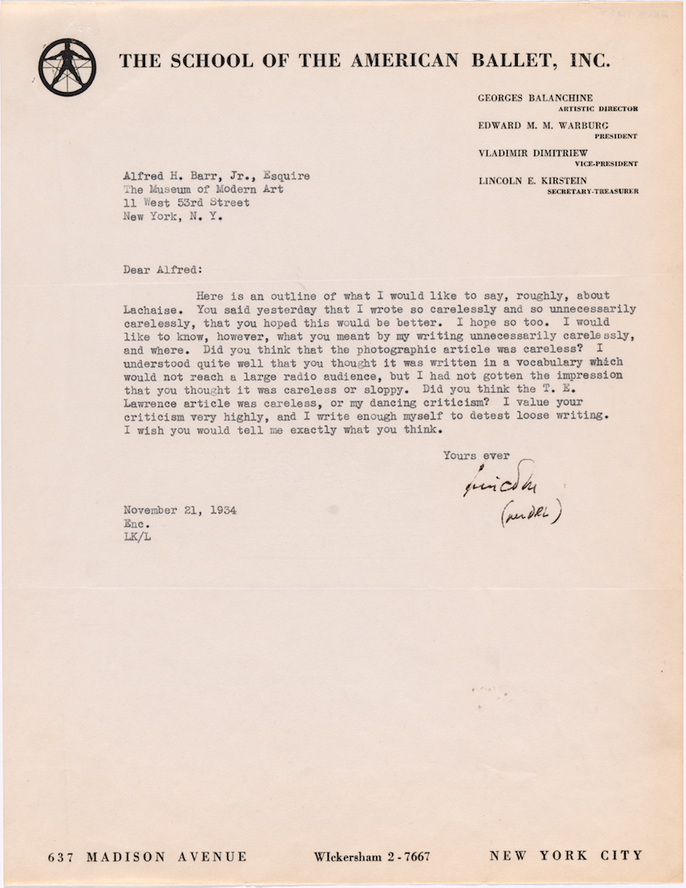

Cover letter from Lincoln Kirstein to Alfred H. Barr Jr. for Kirstein’s outline on remarks on Gaston Lachaise, November 21, 1934. The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition Records, 38.3. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

Kirstein invited the Russian-born choreographer George Balanchine to the US in 1933, and the following year—before any company had been established—they cofounded the School of American Ballet. The Vitruvian Man logo, derived from Leonardo da Vinci’s Renaissance drawing, in the top-left corner of the school’s early letterhead is a perfect distillation of Kirstein’s overarching aesthetic beliefs—whether in dance or in painting, he advocated for an art of exactitude and balance, scaled to the human—and underscores his role as a 20th-century American Renaissance man. That Kirstein is writing to Barr on School of American Ballet letterhead about his essay for a forthcoming MoMA exhibition on the artist Gaston Lachaise encapsulates his myriad pursuits.

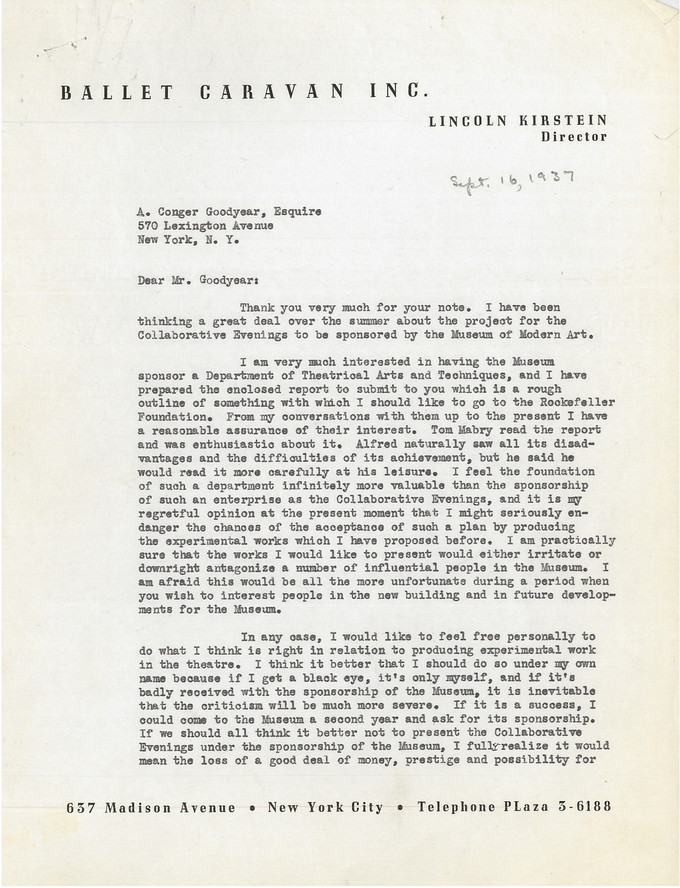

Page one of a two-page cover letter from Lincoln Kirstein to A. Conger Goodyear for an outline of a proposed Department of Theatrical Arts and Techniques, September 16, 1937. Alfred H. Barr Jr. Papers, I.A.29. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

The traveling Ballet Caravan was the only company from these years that Kirstein undertook without Balanchine. Hence his sole name on the stationery’s header (though the address on the footer is that of the School of American Ballet, cofounded with the choreographer). Kirstein writes this pitch to MoMA’s then-president A. Conger Goodyear, for a “Department of Theatrical Arts and Techniques,” on Ballet Caravan letterhead—a testament to the interconnectedness of the performing and research arms of his efforts for dance in this country. Kirstein would enlist visual artists to design ballets for his companies, and then donate those set and costume drawings to the Dance Archives (subsequently a curatorial department of theater and dance) he established at MoMA.

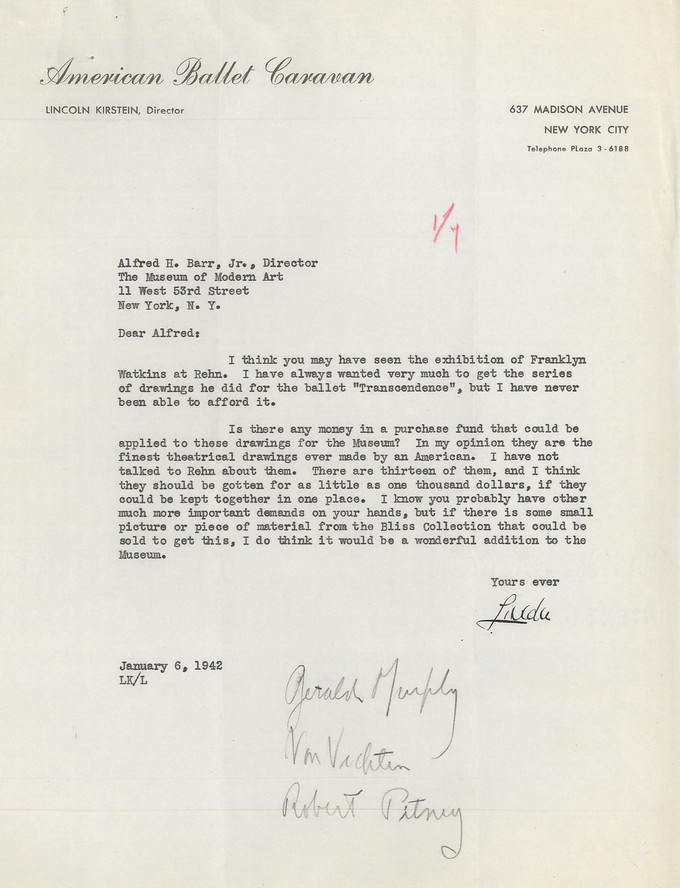

Letter from Lincoln Kirstein to Alfred H. Barr Jr. requesting funds to purchase the Franklin Watkins Transcendence series of drawings for the Museum, January 6, 1942. Alfred H. Barr Jr. Papers, I.A.51. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

Another manifestation of that symbiosis is evident in this Kirstein-to-Barr missive, in which he urges MoMA’s director to acquire Franklin Chenault Watkins’s 1934 designs for the ballet Transcendence, first performed by the producing company of the School of American Ballet in 1934. This time, the note is on letterhead bearing the graceful cursive hallmark of American Ballet Caravan, which was formed in 1941 when Kirstein and Balanchine merged the American Ballet and Ballet Caravan for a tour through South America.

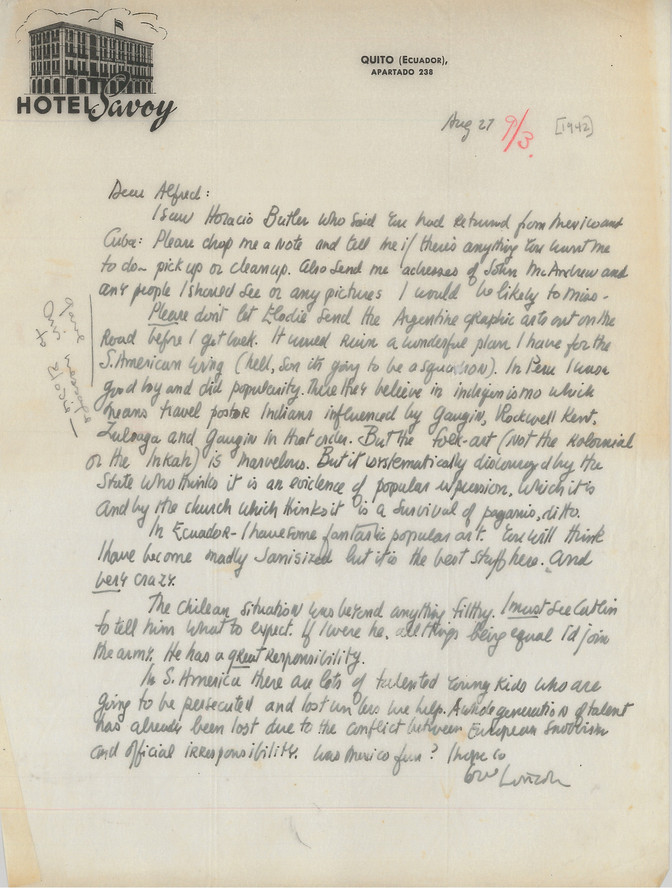

Letter from Lincoln Kirstein (in Quito, Ecuador) to Alfred H. Barr Jr. reporting on his South American travels, August 27, 1942. Alfred H. Barr Jr. Papers, I.A.51. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

The year after American Ballet Caravan toured through South America, Kirstein returned to the continent on a five-month, seven-country acquisition spree for MoMA funded by Nelson Rockefeller (who, as Coordinator of the US Government Office of Inter-American Affairs, also enlisted him to gauge the wartime allegiances of the nations he visited). Kirstein reports his impressions to Barr in longhand on letterhead procured from the Hotel Savoy in Quito, Ecuador, where he has seen some “fantastic popular art.”

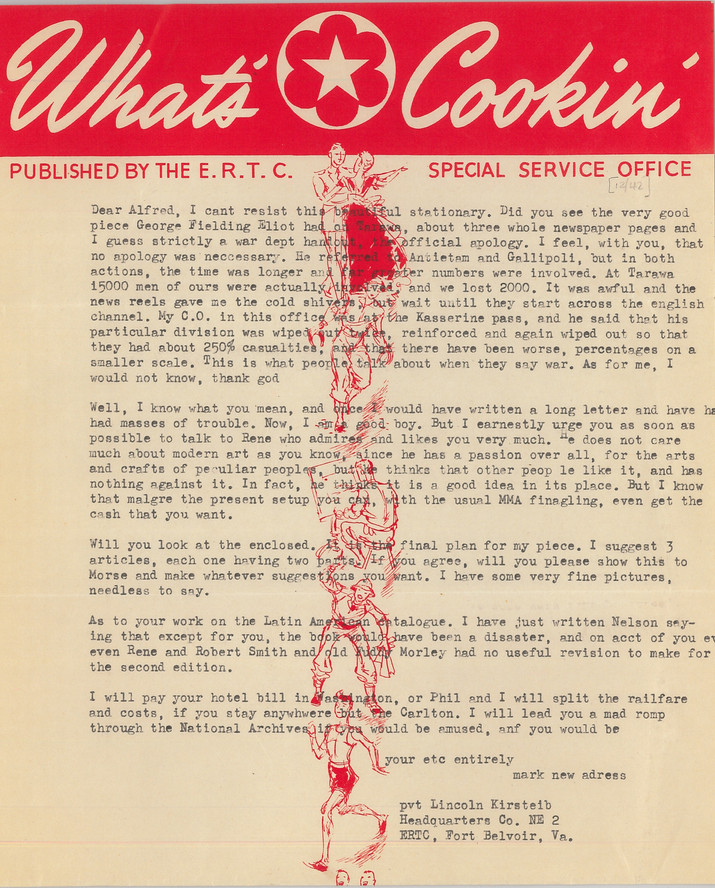

Letter from Lincoln Kirstein (from Fort Belvoir, Virigina) to Alfred H. Barr Jr. regarding war casualties, Rene d’Harnoncourt, and Barr’s status at MoMA, December 1943. Alfred H. Barr Jr. Papers, I.B.28. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

This lively letterhead, on which Kirstein “couldn’t resist” writing to Barr, announces that it was published by the “E.R.T.C,” or the “Engineer Replacement Training Center,” of Ft. Belvoir, Virginia, where Kirstein was assigned as a private in the US Army in 1943. In grim contrast to the cartoonish figures that run like a plumb line down the sheet—men in uniform dancing, playing horseshoes, painting—Kirstein discusses news of the recent Battle of Tarawa, where “we lost 2000” in a faraway Pacific atoll.

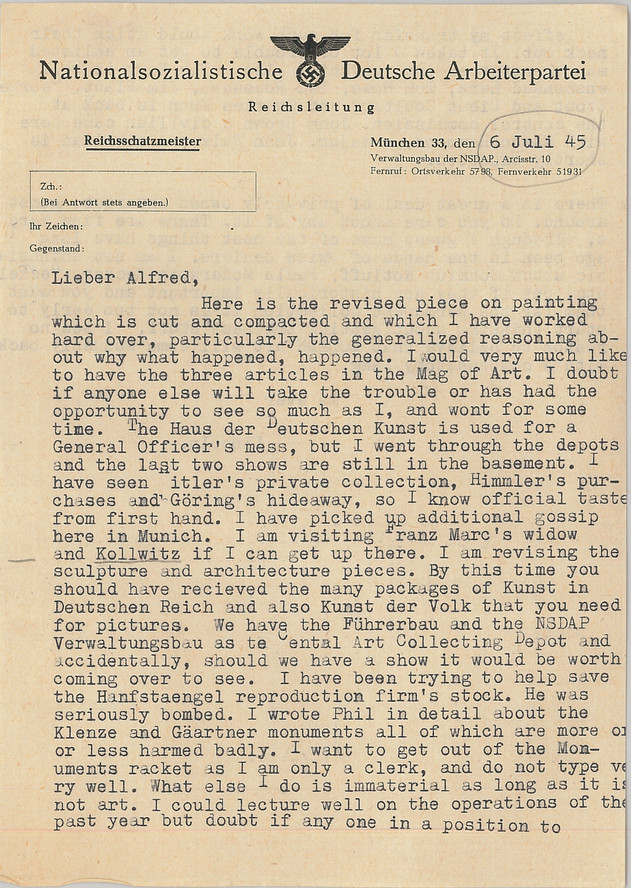

Letter from Lincoln Kirstein (from Germany) to Alfred H. Barr Jr. enclosing his revised article on painting for the “Magazine of Art,” July 6, 1945. Alfred H. Barr Jr. Papers, VI.A.41. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

In an April 29, 1945, letter to his artist brother-in-law Paul Cadmus, Kirstein writes, “I cannot resist showing off this notepaper”—that of Nazi leader Hermann Göring, which he reports finding in Göring’s “private hideout.” Kirstein, who was Jewish, was assigned in 1945 to the US Army’s Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives section as one of the so-called “Monuments Men” who recovered Nazi-looted art. Here, he similarly writes to Barr on the stationery of the National Socialist German Worker’s Party, a precursor to the Nazi party, with its eagle bearing a swastika. “Lieber Alfred,” he opens, with a painful kind of humor, adopting the language of the enemy just as he brandishes its letterhead.

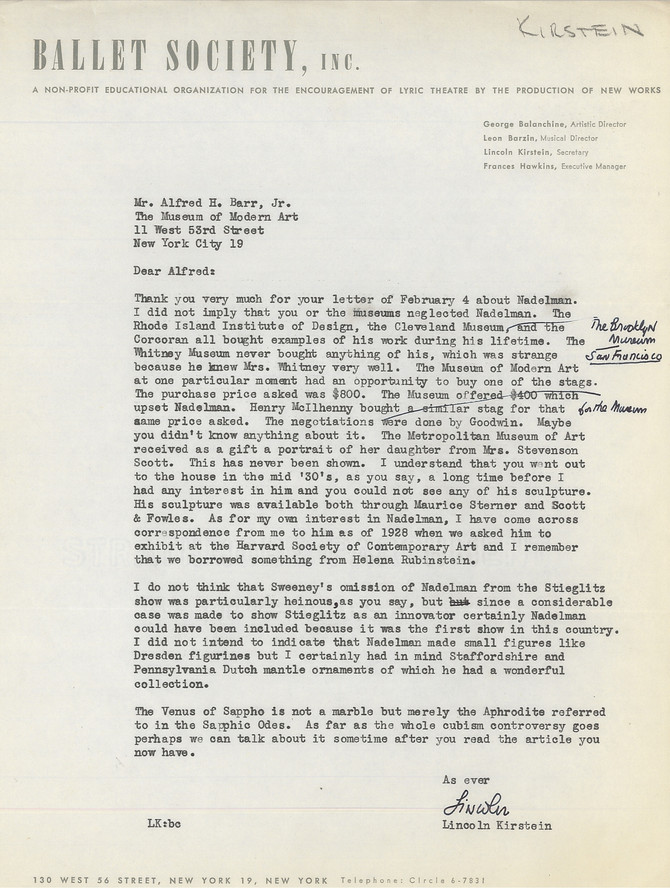

Letter from Lincoln Kirstein to Alfred H. Barr Jr. explaining that he did not mean to imply that Barr or MoMA had “neglected Nadelman,” c. February 1948. Alfred H. Barr Jr. Papers, I.A.102. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

The last of the precursor companies Kirstein and Balanchine established before cofounding New York City Ballet, Ballet Society was, as this letterhead declares, a “non-profit educational organization for the encouragement of lyric theatre by the production of new works.” (The address given on the footer is that of City Center, where Ballet Society was performing at the time.) The topic at hand in this letter to Barr—Kirstein’s feeling that MoMA had not sufficiently supported the artist Elie Nadelman—anticipates the Nadelman exhibition Kirstein would organize for the Museum later that year. This discussion of Nadelman on ballet letterhead prefigures the outsize presence Nadelman would have at New York City Ballet’s future home, when his “Circus Women” sculptures would grace the lobby of the Philip Johnson–designed New York State Theater (now the David H. Koch Theater) beginning in 1965.

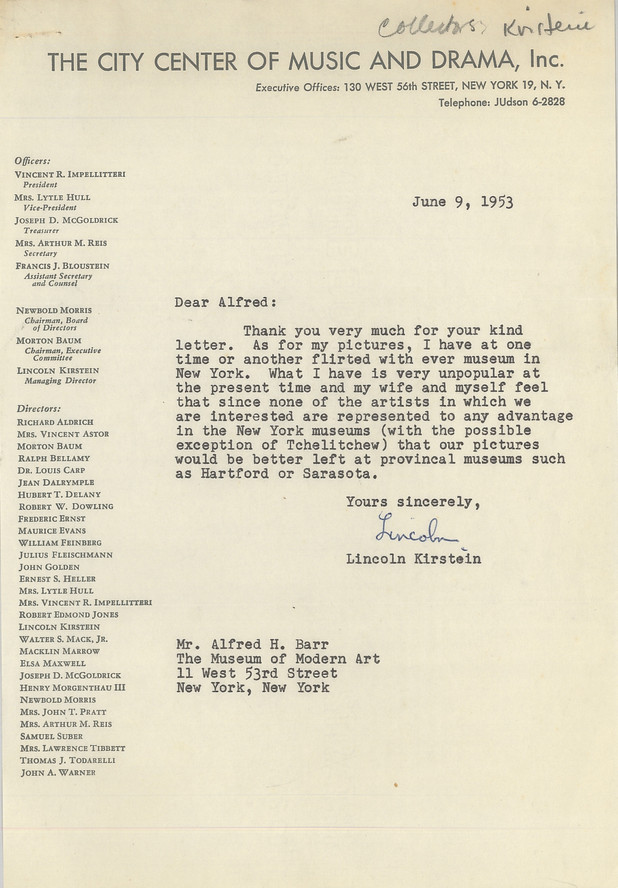

Letter from Lincoln Kirstein to Alfred H. Barr Jr. concerning Kirstein’s collection, June 9, 1953. Collectors Records, 41. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

Here, Kirstein is again writing to Barr from 130 West 56th Street, but this time it’s on the official letterhead of City Center, where the now-established New York City Ballet was officially in residence. The company was founded in 1948, the same year Kirstein wrote a polemic called “The State of Modern Painting” in Harper’s magazine, vigorously expressing his dislike of Abstract Expressionism and MoMA’s support for such work. That piece was in part responsible for a cooling of relations between Kirstein and the Museum, evident in this letter from several years later, in which Kirstein informs Barr that his “pictures will be better left at provincial museums” because “what I have is very unpopular at the present time.”

Thanks to Michelle Harvey, The Rona Roob Museum Archivist, for her invaluable assistance in locating these documents. Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern is on view through June 15, 2019, and is organized by Jodi Hauptman, Senior Curator, and Samantha Friedman, Associate Curator, Department of Drawings and Prints. Get your tickets today.