An Introduction to Adam Pendleton: Who Is Queen?

Read an exclusive excerpt from the exhibition catalogue, about the artist’s project to unfix history.

Stuart Comer

Sep 21, 2021

In 2008, in his Black Dada manifesto, Adam Pendleton declared, “History is an endless variation, a machine upon which we can project ourselves and our ideas. That is to say it is our present moment.” With this manifesto he launched his ongoing Black Dada project: a theoretical framework that draws together works in various mediums to generate systems of abstraction that resist easy legibility, in a collagelike approach that is rooted in two historical texts—Hugo Ball’s Dada Manifesto (1916) and Amiri Baraka’s poem “Black Dada Nihilismus” (1964). Pendleton acts on his manifesto’s declaration by appropriating and recombining historical fragments, texts, images, and sounds—which often hinge on questions of race, politics, queerness, and art history—and resituating them within speculative and open-ended systems. These systems provide the compositional matter at the heart of Pendleton’s project to unfix social, aesthetic, and poetic forms, generating new relationships between traditionally incommensurable subjects.

The Black Dada manifesto is included in Black Dada Reader (2017), a volume containing reproductions of photocopied texts and images that Pendleton had collected in 2012 in a spiral-bound notebook and kept in his studio.[1] This source-book became integral to his everyday practice, and it continues to provide a codex for the Black Dada project as a whole. The present volume, conceived as part of the exhibition Adam Pendleton: Who Is Queen?, presented at The Museum of Modern Art in 2021–22, is the fifth in a series of similar reader-style publications the artist has produced, along with grey-blue grain (2010), i/on interiors (2011), and RADIO (2011). Together they form a score for Pendleton’s art of radical juxtapositions.

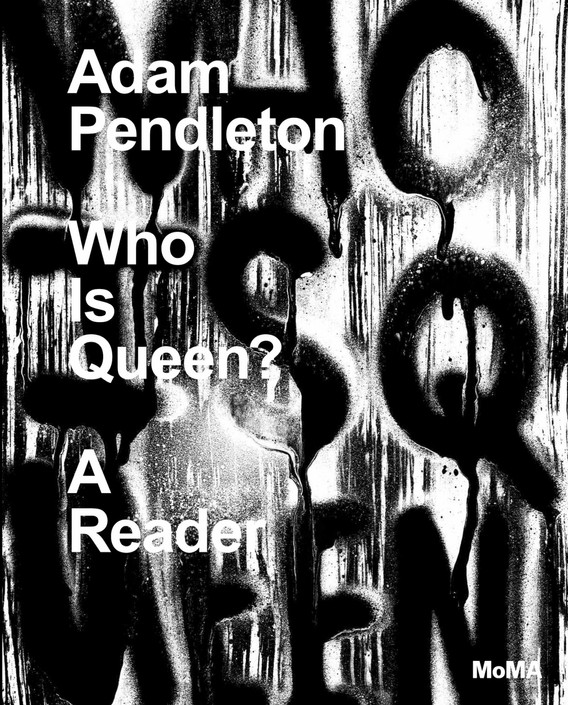

Cover of Adam Pendleton: Who Is Queen? A Reader

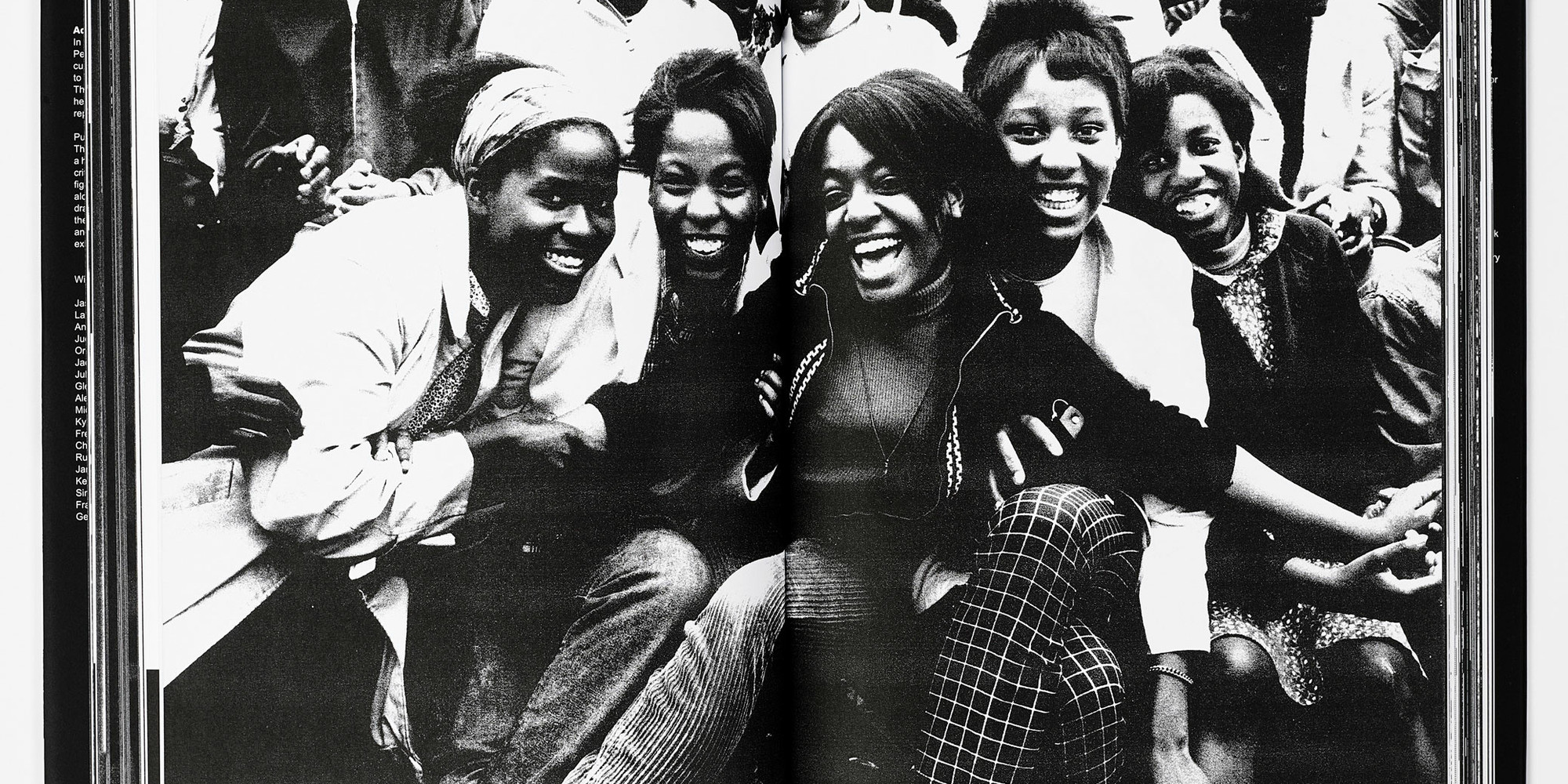

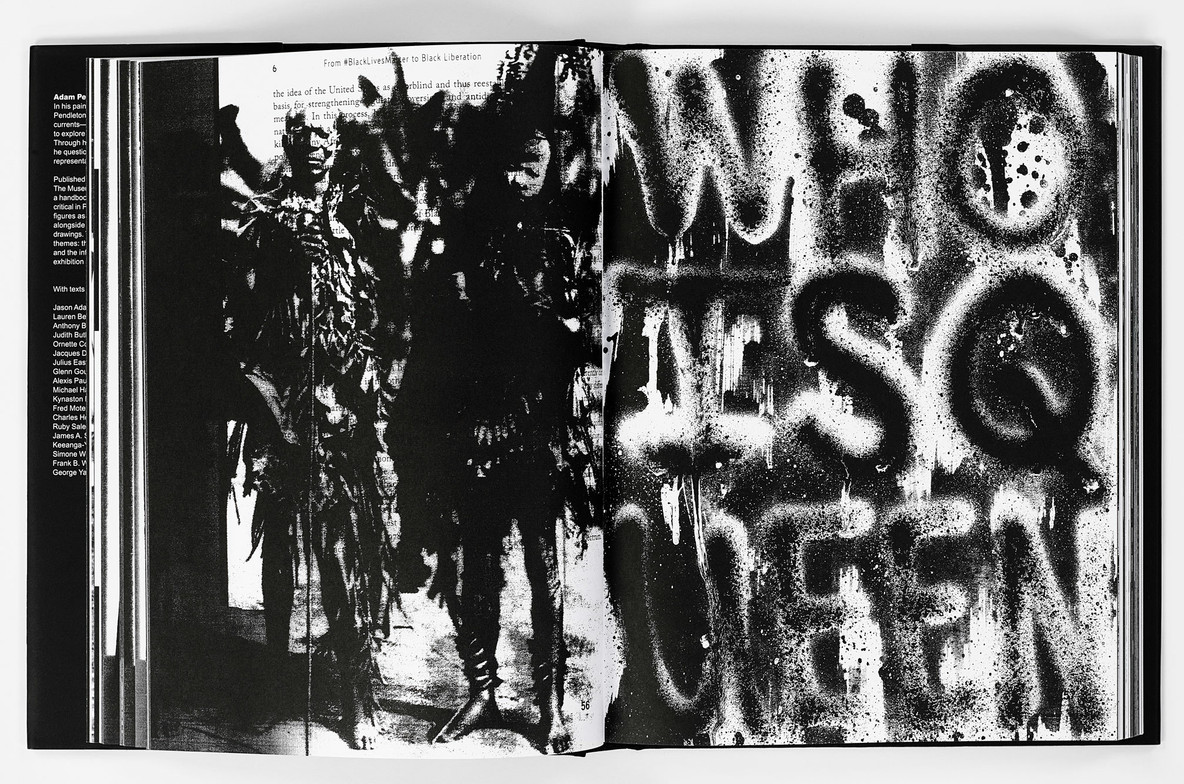

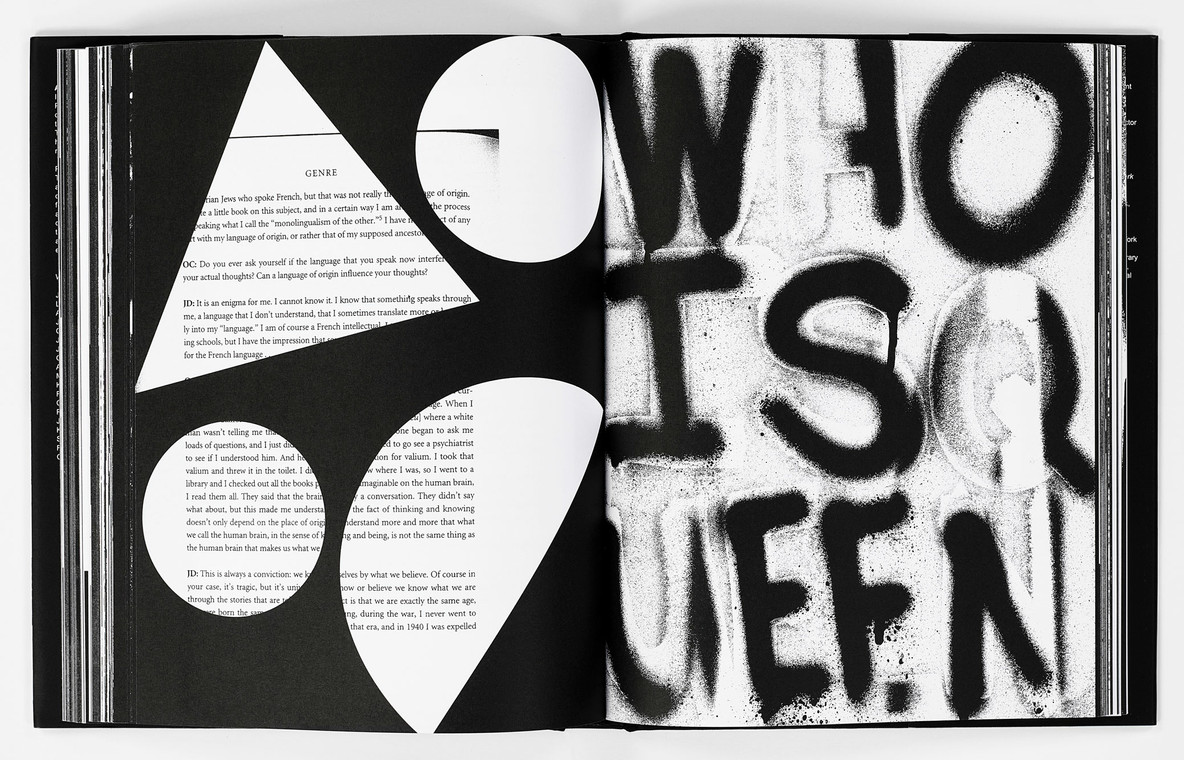

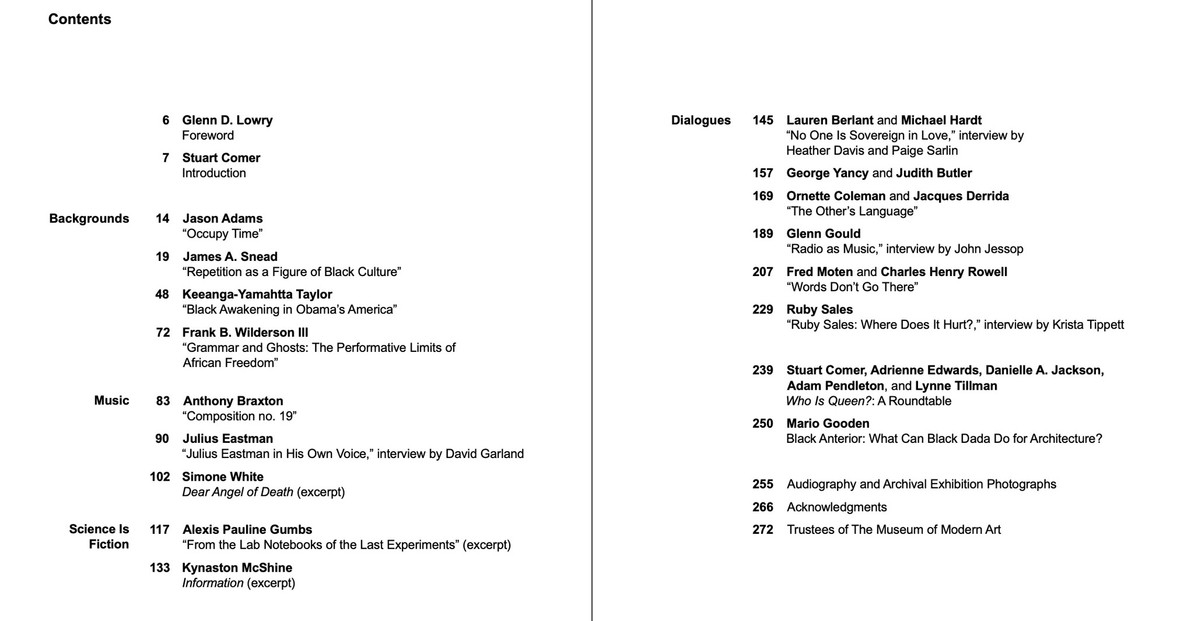

Spread from Adam Pendleton: Who Is Queen? A Reader

Who Is Queen? is an evolution of the Black Dada project. In it, Pendleton has continued his extensive archival research, this time focusing in part on the archives of two institutions—The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and Walker Art Center, Minneapolis—in order to consider the traditional role of museums as repositories. Who Is Queen? also considers the aesthetics of protest, particularly of the Black Lives Matter and Occupy movements, two of the most significant civil-rights campaigns of the past decade. Pendleton conducted field research into sites important to the history of both movements during his Artist Research Residency at MoMA, supported by the Annenberg Foundation, in 2012–15.

Who Is Queen? proposes an experimental encounter between social and artistic forms. It is a superstructure in which the perceived fixity of cultural and institutional memory is placed in contrapuntal relation to the social composition of collective protest and popular movements—to “compositions of bodies and everything that activates them, including voices, gestures, images, affects, architectures, and refrains,” as the artist has said.[2] Who Is Queen? recalibrates the museum, from a rigid frame designed to regulate official accounts of history into an open, generative, and polyphonic device, the machine of endless variation described in the Black Dada manifesto.

MoMA’s atrium, for the duration of the exhibition, becomes the nucleus for this machine. It is transformed into an arena surrounded by floor-to-ceiling scaffolds resembling balloon frames, a type of light-frame construction typical of American domestic structures, but exaggerated to approximate the vertical, aspirational architecture of the modern American metropolis. These five-story towers, painted black and thrown into high relief against MoMA’s white walls, are emblematic of the modernist grid, echoing architectural forms as well as the modular cubes of the artist Sol LeWitt, whose use of serial forms, repetition, and open structures and systems have been a touchstone for Pendleton, a physical counterpoint to his interest in the recombinatory possibilities of language. The scaffolds provide supports for layers of Pendleton’s works—a spatial collage of large-scale paintings, based on collaged and spray-painted text; drawings silkscreened on Mylar film, combining language with geometric forms, images of African art, and the artist’s sketches and visual “notes”; and sculptures composed of simple black lines and shapes. Within this field of fragmented and appropriated forms, spray-painted phrases proclaim, “Who Is Queen?” and “The Now I Am,” dispersing Pendleton’s voice into the broader system of the installation, destabilizing divisions between the individual and the collective.

A sound piece composed of materials from museum archives and other sources plays continuously. This cut-up sound collage, made of layered, looping fragments, is anchored by three elements: a reading by the poet Amiri Baraka at Walker Art Center in 1980; a recording by the violinist, guitarist, and composer Hahn Rowe from 1994; and a recording, made on a smartphone, of a Black Lives Matter demonstration in Manhattan in 2014. These recordings are mixed in among music by Linda and Sonny Sharrock, Jace Clayton, Frederic Rzewski, Julius Eastman, and Laura Rivers.

Additional voices are provided by a series of podcasts organized by Pendleton, broadcast online, and released monthly throughout the period of the exhibition, which pair activists, writers, and public intellectuals in conversations that are subsequently fed back into the soundtrack. The voices of the participants—including Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Jack Halberstam, Michael Hardt, Susan Howe, Matana Roberts, Ruby Sales, Tyshawn Sorey, and Lynne Tillman—are metabolized into the broader mechanics of the project: captured, modified, displayed, and played back, critically miming a museum’s traditional operations.

A video portrait of the author and queer theorist Jack Halberstam is projected on a large screen within the installation. This new work, which builds on Pendleton’s series of portrait films of subjects such as Yvonne Rainer, Lorraine O’Grady, and Ishmael Houston-Jones, alternates with a second video, composed of archival footage and photography of Resurrection City, a protest camp set up on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., in 1968.

Who Is Queen?’s immense assemblage of paintings, drawings, sculptures, moving images, and sounds, barely contained by their architecture, are drawn into relation through counterpoint. In a musical composition, counterpoint, or the contrapuntal, refers to a complex development of simultaneous voices in tension: point against point. Organized above a foundational cantus firmus (a fixed, often preexisting melody), voices in counterpoint form overlapping lines, rearticulating and modifying one another in permutational clusters. Rather than a duel of vertical harmonic oppositions or a more strongly punctuated call-and-response, counterpoint is a continuous system of folds and fractals, a horizontal music, weaving dynamic threads into a detailed tapestry.

Another kind of contrapuntal motion is suggested by the idea of the politics of love developed by the American political theorist Michael Hardt, who draws on both the legacy of twentieth- and twenty-first-century social movements and the metaphysics of Baruch Spinoza. For Hardt, the politics of love might be understood as contrapuntal motion set against classical, coupled, or even ethno-national love, the kind of love in which the two or the many become one by way of transcendent identification. Instead, he conceives of love as a relation that transforms its relata— not by unifying these relata and liquidating their differences but by autonomizing them, increasing their agency as they undergo change. It is only this love which can serve as the motor for a truly democratic politics: a love which, like counterpoint, remains within a series of differences and returns, needing no vertical axis of unification.

To further articulate the politics of love, Pendleton has looked to the civil-rights activist and theologian Ruby Sales, who has formulated an ethos directly shaped by Southern “Black folk religion” and the struggle against American apartheid.[3] Sales’s work in public theology traces this religion back to the informal religious congregations that emerged under chattel slavery in the United States. These were congregations built without official preachers or physical houses of worship. In her view, such congregations find continuity instead in the mass mobilizations of the twentieth century. The role of organized religion and its emphasis on love and nonviolence in the Civil Rights Movement is well known, but Sales argues that it was a countercultural politics of love—rather than a more sublimated civic or religious love—that was fundamental to the movement.

Pendleton began to develop a polyphonic approach to the audio component of Who Is Queen? in 2010. It is loosely modeled on the “contrapuntal radio” documentaries of the pianist Glenn Gould, whose Solitude Trilogy, produced for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation between 1967 and 1977, brought the form of counterpoint to bear on social and environmental matters.[4] By superimposing the voices of interviewees, Gould constructed dense audio landscapes that, in Fred Moten’s description of them, “[disrupt] documentary linearity” and manifest “a sort of . . . compositional overhearing . . . where simultaneity works through and over sequence.”[5] The “all at once” broadcasts, anchored by ambient cantus firmi (the sound of a train, or the ocean, or a church choir), signal a line of escape from the customary “one at a time” logic of the discussion or dialogue.

Who Is Queen? continues to engage with the entanglements of liveness and mediation, improvisation and script, and system and subject, as well as with the torsions, contractions, and expansions of historical time. Counterpoint, for Pendleton, as a conceptual and aesthetic principle, is a way to affirm complexity and invent a new space for aesthetic and political experimentation.

Want to read more? Pick up a copy of the Adam Pendleton: Who Is Queen? catalogue.

Adam Pendleton: Who Is Queen?, organized by Stuart Comer, The Lonti Ebers Chief Curator, with Danielle A. Jackson, former Curatorial Assistant, and Gee Wesley, Curatorial Assistant, with the support of Veronika Molnar, Intern, Department of Media and Performance, is on view at MoMA through January 30, 2022.

Notes

1. Adam Pendleton, Black Dada Reader (London: Koenig Books, 2017), 333–45.

2. Pendleton, artist statement for Who Is Queen?, 2019.

3. Ruby Sales, “Where Does It Hurt?,” interview by Krista Tippett, September 15, 2016, On Being, onbeing.org/programs/ruby-sales-where-does-it-hurt/; see page 232 in this volume.

4. “Radio as Music: Glenn Gould in Conversation with John Jessop,” The Canadian Music Book, Spring–Summer 1971; reprinted in The Glenn Gould Reader, ed. Tim Page (New York: Random House, 1984), 374–88; see pages 190–206 in this volume.

5. Fred Moten, “Sonata Quasi una Fantasia,” in Black and Blur (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2017), 47.

Related articles

-

A Matter of Memory: Shigeko Kubota’s Video Sculptures

Read an excerpt from the exhibition catalogue about how the artist transgressed boundaries to create something entirely new.

Gloria Sutton

Sep 17, 2021

-

Rolling Sculpture: on the Automobile’s Aesthetics

Read an exclusive excerpt from the exhibition catalogue Automania, about the provocative history of the car as an art object.

Juliet Kinchin

Jul 14, 2021