“Abstraction is as political as anything else.”

Adam Pendleton

In 2008, in his Black Dada manifesto, Adam Pendleton declared, “History is an endless variation, a machine upon which we can project ourselves and our ideas. That is to say it is our present moment.” Pendleton is a New York–based artist whose work uses linguistic, political, and historical material in unlikely forms and configurations. He creates paintings, drawings, moving-image works, sculptures, and installations that transform received narratives about the past, breaking down rigid historical categories to open up new possibilities and directions for the future. Pendleton’s work attempts to align seemingly disparate histories of artistic form and political action, striving to articulate “the ways in which we simultaneously possess and are possessed by contradictory ideals and ideas.”

In 2008, Pendleton began to develop his work through the idea of Black Dada, an evolving inquiry into the relationships between Blackness, abstraction, and the avant-garde, and their respective histories. “Black Dada is a way to talk about the future while talking about the past,” Pendleton writes. Rooted in American poet Amiri Baraka’s 1964 poem “Black Dada Nihilismus” and German poet Hugo Ball’s 1916 “Dada Manifesto,” Pendelton’s Black Dada is the name of an early text/performance and, soon after, a series of paintings.

Black Dada (LK/LC/AA) (2008–09) is an early entry in the Black Dada series, which consists of monochromatic abstractions defined by a set of rules for construction. In each instance they involve the selection and placement of an enlarged photocopy of one of conceptual artist Sol LeWitt’s Incomplete Open Cubes (1974) and one or several uppercase, sans-serif letters from the title (BLACK DADA). These elements are composed and screenprinted in black on two black canvases, which are then hung one above the other in a diptych. The letters no longer form complete words, but rather become anagrams with neither beginning nor end. Like LeWitt’s Incomplete Open Cubes, the letters are an open system, the building blocks for a new vocabulary that allows Pendleton to rephrase history in the present. Paired with the image of LeWitt’s iconic work, Pendleton’s contrasts fragments from the past to ask, "What future might appear out of this act of perception?"

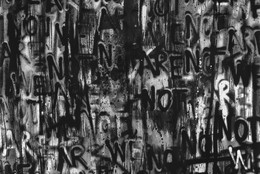

Pendleton has described the Black Dada paintings as a stage, an architectural foundation for other bodies of work that extend Black Dada’s system of notation, manipulation, and variation. His System of Display (2008–), for instance, is a series of small mirrors in plexiglass display boxes on which various found images—largely historical—are paired with fragments of text. The Code Poem sculptures (2009–) consist of different arrangements of simple shapes derived from the work of poet Hannah Weiner. Pendleton's drawings on Mylar (2014–) begin with a process of mark-making and language-making. Using spray-painted and painted sketches, visual “notes,” and collage, he creates compositions, some of which feature images of African art and other reproductions from books in the artist’s library. In his Untitled (A Victim of American Democracy) (2016–18), OK DADA OK BLACK DADA OK (2017–18), and Untitled (WHO WE ARE) and Untitled (WE ARE NOT) (2018–) paintings, he processes layered, repeating, spray-painted language on large-scale canvases.

Since 2012, Pendleton has also been producing video portraits of artists and thinkers. Taking American modernist poet Gertrude Stein’s “text portraits” as a point of departure, these video portraits do not render their subjects in the mode of straightforward documentary but rather as a kind of collage, cutting between personal memory and texts and images. Pendleton’s subjects have included Lorraine O’Grady (2012), David Hilliard (2011–14), Yvonne Rainer (2016–17), Ishmael Houston-Jones (2018), Kyle Abraham (2018–19), and Jack Halberstam (2021).

Stuart Comer, The Lonti Ebers Chief Curator of Media and Performance

Note: opening quote is from “History Is Never Finished: An Interview with Adam Pendleton,” MoMA Magazine, February 18, 2022. https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/703.