Why Nauman Now?

Bruce Nauman’s work remains viscerally urgent today.

Taylor Walsh

Dec 7, 2018

Although Bruce Nauman is one of our truly indispensable living artists—among the key figures to emerge from the 1960s who laid the groundwork for much of what followed—it’s been several decades since he’s been the subject of a comprehensive exhibition.

The last Nauman retrospective began its tour 25 years ago. That show was also co-organized by Disappearing Acts lead curator Kathy Halbreich, and it traveled to MoMA in 1995. In 2018, a full-career retrospective can cover over 50 years of Nauman’s creative output. It’s the first opportunity for a whole generation of viewers to see the work in its entirety, to get a sense of how it’s changed over time and why looking at Nauman remains urgent today.

Nauman is not a political artist in any overt or declarative way, yet his work traffics in themes that resonate now and trouble the present.

State-sanctioned violence, for example, viscerally evoked by the confinement of his Double Steel Cage Piece:

Bruce Nauman. Double Steel Cage Piece. 1974

Or the danger of labels that allow us to treat other people as abstractions, as in the reference to antiquated racial categories in White Anger, Red Danger, Yellow Peril, Black Death:

Bruce Nauman. White Anger, Red Danger, Yellow Peril, Black Death. 1984.

Or surveillance technologies that capture and circulate our images in ways we can’t control—and all of the anxieties that come with inhabiting a body under those conditions.

Bruce Nauman. Corridor Installation (Nick Wilder Installation). 1970.

Nauman’s use of physical structures to provoke emotional reactions is seen in his large-scale corridors, rigged with closed-circuit cameras and monitors that display your image but defy expectations.

Nauman’s work doesn’t yield to easy interpretation, and it has never slotted neatly into ready formal categories. Since the mid-1960s he has expanded definitions of sculpture to include everything from neon signs to video projections to running water. He constantly shifts between all these and more, never conforming to a signature style.

Bruce Nauman. Seven Figures. 1985; Three Heads Fountain (Three Andrews). 2005; and Three Heads Fountain (Juliet, Andrew, Rinde). 2005.

Critical discussions of Nauman’s work tend to dwell on its sheer variety, and the less sympathetic ones often associate all that flux with a lack of coherence. But we want this exhibition to point to a through-line, something that persists, and disappearance has been one such recurring impulse through all phases of his long career. Instances of removal, deflection, and concealment crop up again and again, whether in strips of neon that were supposedly formed around the artist’s now-absent body:

Bruce Nauman. Neon Templates of the Left Half of My Body Taken at Ten-Inch Intervals. 1966; with Light Trap for Henry Moore, No. 1. 1967; and Device to Stand In. 1966

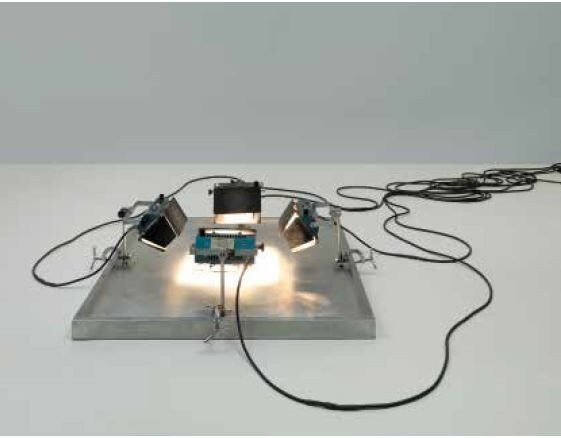

Or four thousand-watt theatrical lightbulbs trained on an empty center:

Bruce Nauman. Lighted Center Piece. 1967–68.

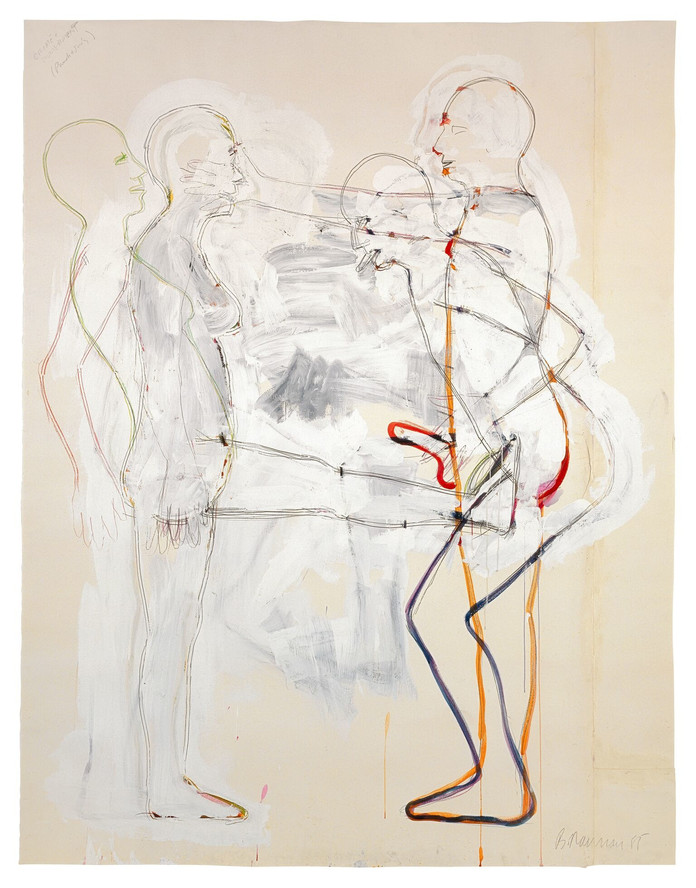

Or works on paper in which the erasures nearly overwhelm the drawing itself:

Bruce Nauman. Crime and Punishment (Punch and Judy). 1985.

Or video monitors that can't quite capture your image as it slips from view:

Bruce Nauman. Going Around the Corner Piece. 1970

Or Nauman’s own image, marked by age and fractured into a grid of spinning parts:

Still from Contrapposto Studies, i through vii (detail). 2015/16.

From this sampling, it’s clear that his work abounds in gaps and holes and partial figures. Nauman’s principle theme is the body—both his body and ours—as a vessel and a source of information, and he reveals it to be an unstable foundation for understanding our place in the world.

Nauman has said that, for him, making art is about “doing things that you don’t particularly want to do, putting yourself in unfamiliar situations, following resistances to find out why you’re resisting.” The same can be said for our experience in viewing a Nauman exhibition: his work issues a challenge that calls on us to do far more than simply look.

Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts is on view at MoMA and MoMA PS1 through February 25, 2019. Buy tickets today. The exhibition is organized by Kathy Halbreich, Laurenz Foundation Curator and Advisor to the Director, The Museum of Modern Art; with Heidi Naef, Chief Curator, and Isabel Friedli, Curator, Schaulager Basel; and Magnus Schaefer, Assistant Curator, and Taylor Walsh, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Drawings and Prints, The Museum of Modern Art.

Related articles

-

Notre Dame, an Inspiration

In the aftermath of the Notre Dame fire, MoMA curators reflect on works that depict the cathedral not only as an enduring work of art, but as a landmark for modern artists.

Glenn D. Lowry, Ann Temkin, Martino Stierli, Sarah Meister, Samantha Friedman, Phil Taylor

Apr 17, 2019

-

The Everyday Life of Simone Forti’s Dance Constructions

A performance diary in photographs

Jason Riker, Ana Janevski, T. Jean Lax, Martha Joseph

Jan 28, 2019