Sable Elyse Smith’s New Opera If you unfolded us

Smith and fellow artist Nikita Gale talk about building architecture for a sonic world.

Sable Elyse Smith, Nikita Gale

Jun 27, 2024

In July, as part of the annual Studio Sound series, MoMA will premiere seven songs from an ambitious new opera by the interdisciplinary artist and writer Sable Elyse Smith. Created in collaboration with composer David Dominique and vocalist Freddie June, Smith’s If you unfolded us is an immersive multimedia work for two voices (Freddie June and S T A R R Busby) and an eight-piece chamber ensemble. It is set against the backdrop of a developing storm and explores the drama of everyday life, intertwining a love story between two Black women with the protagonist's journey of self-discovery.

For this conversation, Smith spoke to fellow artist Nikita Gale about spectacle, the artistic process, and early 2000s music videos.

—Martha Joseph, Associate Curator, Department of Media and Performance

Nikita Gale: How long have you been working on this project?

Sable Elyse Smith: I had been telling people that I was working on an opera since at least 2019. So it’s been in my head for a while, but then I got this invitation from Martha Joseph to do a music/sound related project at MoMA. The composer and I started chit-chatting and feeling our way through sound references and trying to build out a kind of architecture for quite a few months. Then I had to start writing the libretto, so maybe January for real for real.

NG: It sounds like you might be similar to me in terms of how you work, where you think about something for a long time and then you’re like, “Okay, I got a deadline, I’m gonna start.”

SES: Yes, I’m always thinking about shit, and then a deadline is the catalyst.

NG: I mean, especially creating an opera…I’ll admit, I don’t know a lot about the history of opera. The first thing I thought of when you reached out to me was June Jordan’s opera I Was Looking at the Ceiling and then I Saw the Sky. I actually have the physical copy of the libretto.

For my piece for the Performa Biennial, I worked with this really great producer George Miller, who works specifically with contemporary opera, so it started to become more of a thing for me. Later, I went to one of the operas he directed. So I was like, “I feel like it’s in my universe now, this awareness about opera and its structure.”

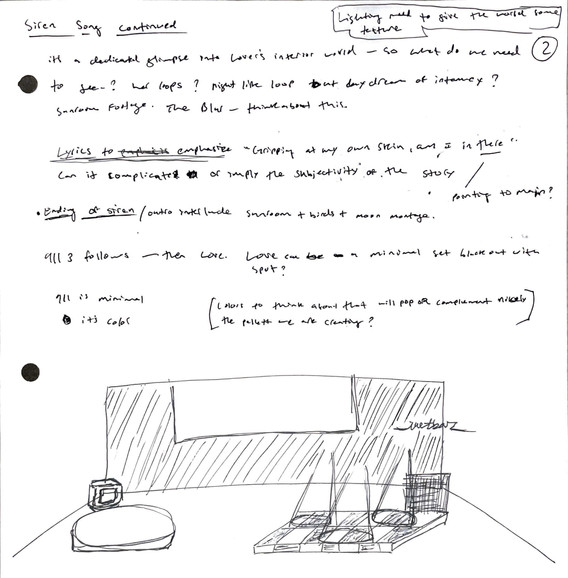

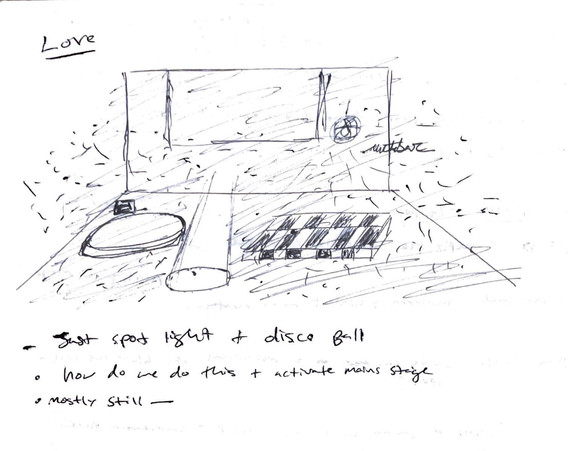

Notes and sketches for Sable Elyse Smith. If you unfolded us. 2024

Notes and sketches for Sable Elyse Smith. If you unfolded us. 2024

SES: I don’t have that in-depth history or knowledge of opera either. Randomly, my friend Cal invited me to go to the Met around 2016. That was the first time I had been to the opera.

I loved the spectacle of it. Cal is an artist and furniture marker. So, the whole time—like, this shit is in German!—we’re just sitting here talking and geeking out about the set and everything. There’s all this dense layering that happens, especially with something on the scale of the Met.

After that, I started going to the theater a lot more and seeing musicals (which I hadn’t previously been that into), and just thinking through all of these instances of liveness and performance and doing research about it. Also, I was really attracted to this kind of larger-than-life form that was interdisciplinary. Which for me isn’t that far away from church or a cookout honestly.

NG: I almost want to roll back my earlier statement about not being so familiar with opera because so many things could fall under that category, formally speaking. I pulled up a definition of “opera” and it says, “Opera is a form of theater in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a work is typically a collaboration between a composer and a librettist. It incorporates a number of performing arts such as acting, scenery, costume, and sometimes dance or ballet, typically given in an opera house.” So, if you were to just go off of that definition, yeah, you’re absolutely right. It’s church. I would say it’s also a lot of what we experience through media in general. If it is about music being a fundamental component and dramatic roles taken by singers, that’s also music videos.

SES: Definitely. Thinking about early 2000s music videos, my mind always defaults to rap and R&B, like the Hype Williams era, which is the most sumptuous, the most spectacular, the most performative.

But the term “opera” creates a context around it, though opera literally translates to “work.” And yet there are all these expectations that people have. When I tell people I’m making an opera, immediately there’s a certain type of sound that’s going to come to mind. And the thing we’re making will not be fulfilling those expectations.

NG: Oh, that’s exciting.

SES: I always like to kind of fuck shit up just in general. That’s part of the attraction for me, because it’s so entrenched in a certain class, a certain elitist...

NG: Eurocentrism.

SES: Yeah. And so taking all of these expectations and doing the opposite is an interesting proposition to me.

NG: Tell me about your relationship with this composer.

SES: His name is David Dominique. The curator Amber Esseiva is really good friend of mine, and Dave is her husband. He’s a Richmond-based guy and recently started working on an opera of his own. Amber had been telling him, “Oh, you should talk to Sable.” We started chit-chatting more and more about music, and I did a deep dive into his work. So when I sat down with Martha and I was like, “Okay, I guess I’m gonna do this,” I thought: Okay, it’s Dave. And he’s been a dream collaborator.

NG: Your relationship with the composer is a very intimate relationship. You’re writing the libretto and this composer is creating everything else around this text. I’m curious how you’re putting it together with David.

SES: The libretto is kind of the ground. It creates the structure to think about both length and the narrative, and emotional arcs.

Once Dave said “yes,” I got to work on the libretto. In the meantime, he asked me to make some playlists. So I’m making these playlists that feel like references…almost like flash cards. It’s like, “here’s a vocabulary,” and now when we start speaking, we can use this vocabulary even though these references might fall away.

The one definitive thing I had in mind was a narrative through songs anchored in contemporary Black popular music. Particularly R&B. I wanted to see how wild we could get.

NG: Quiet Storm genre.

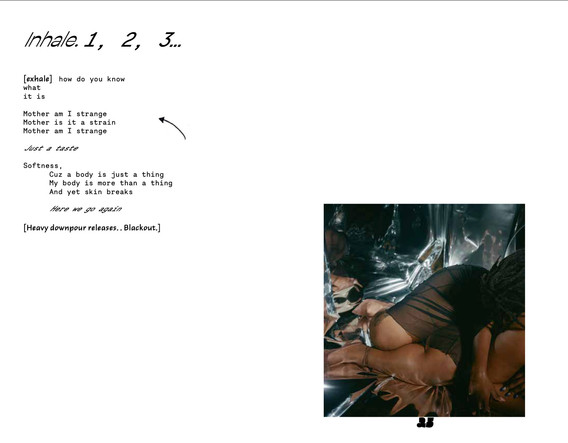

Excerpt from the libretto for Sable Elyse Smith. If you unfolded us. 2024

“How do we put these familiar, dope, nostalgic forms...into a space that’s a little bit wilder and can be manipulated to do these other things we want it to do?”

Sable Elyse Smith

Portrait of Nedjra Manning and Freddie June (Shala Miller), lead vocalist in Sable Elyse Smith’s If you unfolded us, 2024

SES: Yeah, but I wanted to complicate it, too. Popular music is effective because it has a framework that does a thing that is in our body, that we’re familiar with. But how do we think about chamber music or classical music and these other forms like jazz, where song forms or structures are a bit more complex and there has been more space for abstraction or experimentation outside of formula and the market?

In other words, how do we put these familiar, dope, nostalgic forms (which also operate as a kind of shorthand) into a space that’s a little bit wilder and can be manipulated to do these other things we want it to do? It’s like the gems on the B-side, not the radio single. I was also thinking about this history of sampling. So in the opera there’s lots of digital shit plus this chamber ensemble and a rhythm section all melting into each other.

NG: I really loved this document that you shared with all these notes, images, and things about the weather, and the reference to Toni Morrison’s Beloved. I love looking at this stuff.

SES: Thank you. I’m a sucker for “books” like this or just the printed matter around projects. This is meant to be a kind of playbill, or the liner notes. It’s important to me because I’ve been doing so much reading around this project and the narrative I’ve been building. This object in itself is an act of sampling. It’s a beat. Weather is both the content and a metaphor in the work. There is a storm, and the triangulation between performance, music, and text shapes it.

NG: The storm in your work makes me think about the idea of the stage as a container for a type of atmospheric activity or weather: these shifts that influence the environment of the narrative that is taking place. And so, to me, the things that might encompass that definition of weather or atmosphere on the stage include the ensemble, the singers, the lighting, the set design. All of these things are influencing and informing what is happening. I want to think of the libretto as the figure in the scene. Because it is the one thing that’s more or less stable. The narrative is the fixed subject.

SES: That’s an interesting way to think about it. I am interested in these elements being layers that impress upon each other but maybe complicate the audience’s understanding or expectation of what they are witnessing, or where their attention might be.

In this piece the weather is an entity and a quotation of a larger societal reality. It’s that shorthand again, and I’m curious to see how it plays out and how legible it ends up being. But as the piece goes further, I want to shape how and where it moves through the room and hopefully through the audience.

NG: Much like weather. You can only predict it so far in advance.

I know that you mentioned sampling being a component of this work. Often the sampling helps to feel in a very visceral way how labor functions, the real tax that it has on the body of the performers, especially in opera. It is the full body being given over to the text. Can you talk about your relationship to sampling?

SES: I think it came up first in the initial conversations and thinking about, “how do we create the architecture for a sonic world?” This idea of sampling became one way. And when you think of a sample in its most elemental form, especially in hip-hop, there’s the loop. I also wanted that to be a sonic history from which to build.

I selected seven songs plus some overture material. But then I had to ask: how does it resolve itself? How does it end? What is the crux of this story? The answer actually is that it keeps going. Another day just happens again, but maybe with a little more knowledge, more self awareness, which isn’t a small thing and not everyone is able to recognize it in the same way. So that loop felt natural for the story and even conceptually for the music and even a storm. All of these different things working upon the world and the person and the climate.

NG: It’s interesting to hear you talk about loops as almost a way of referencing or citing or reusing a previous person’s labor to build something else on top of that or to be in conversation with something. Because there’s also something that feels very resourceful or restorative about making use of ancestral work that is recorded, so that you don’t have to do that work but can build off of it. Or uses it as a foundation. Because then it does this thing where, through citation, it continues to make the cited material relevant, maybe to a different audience or in a different time and place or using a different location and form.

I love the idea of an R&B song being in an opera. There’s something incredibly powerful and important about the role of sampling in that context, where you use the form and question what it is. So much other stuff is opera, we just don’t call it that.

SES: Back to that point about labor: the acknowledgement, shorthand, and citation of these samples is important. The work can be multilingual in that way. The girls that get it, get it. I haven’t yet gotten to the end of Daphne A. Brooks’s Liner Notes for the Revolution. There’s a passage in there that talks about the erasure of Black femme voices but flips it, saying that the voice and the sounds themselves are monuments. That we erect them, for ourselves, of ourselves. I think about that in relation to the samples as citations.

Also just zooming out to the art context: interviewers are always asking, “What artists are you referencing? Or what theories? Which art historians?” And nine times out of 10 I’m like, I’m referencing none of those motherfuckers. I’m thinking about LA or my grandmother or B. B. King or Anita Baker or Chaka Khan or Gwen McCrae or I’m thinking about my mom and I driving from the east to the west coast listening to one Patti LaBelle tape on repeat.

I’ve also been reading Alexander Weheliye’s Feenin: R&B Music and the Materiality of BlackFem Voices and Technology. There’s a reference in it that I’m thinking about, about a shift from the late-’80s-’90s R&B melismatic singing, with that gospel influence, which is a particular type of emotional labor that people expect from Black femmes to facilitate a catharsis. He’s citing another scholar making an argument that there’s been a contemporary shift in vocal identity, one less reliant on that kind of flourish or ornamentation—arguably to refuse or mitigate that emotional labor through the Black femme voice. I’m still sitting with that, but there’s something interesting in that, too, as you bring up the notion of labor.

NG: But also with this term, labor, it’s not just the performer working. Because you’re also having to contend with the work that you’re doing as someone who is having to experience the performance in the audience. But what you’re describing with the expectations that are placed on Black femme bodies in performance, there’s also that space between the viewer and the performer where you’re dealing with your own expectations. And often in traditional versions of these performances those expectations are met and there’s not much that’s challenged in a way that is off-putting. But in an arts context, we get to get messy in that space between expectations and what is actually happening. So I’m interested to see…

SES: …if we’re brave enough.

Studio Sound: Sable Elyse Smith is on view at MoMA July 3–14, 2024.