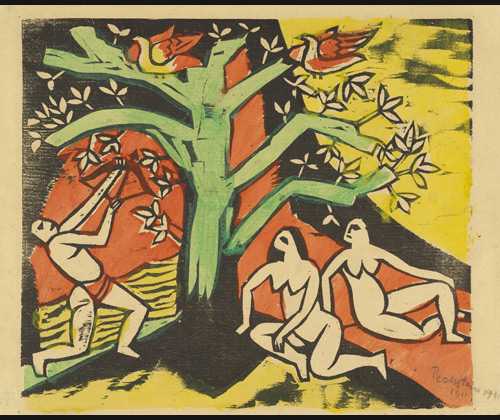

Vasily Kandinsky

The Church from Xylographs (Xylographies)

1909 (executed 1907)

In this woodcut, Kandinsky evokes a fairytale world of Old Russia, a place filled with onion-domed churches and girls in richly embroidered costumes. As a young ethnography student, Kandinsky had traveled to remote regions of Russia, where he was inspired by the simplified forms and decorative patterning of local folk art.