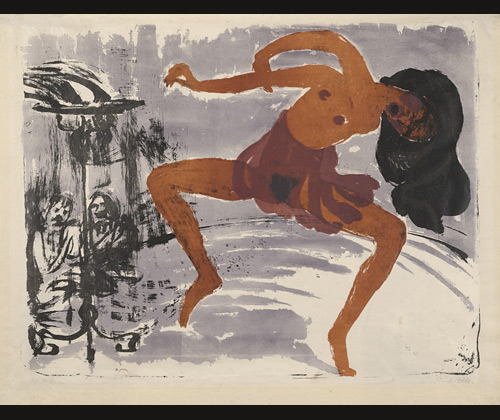

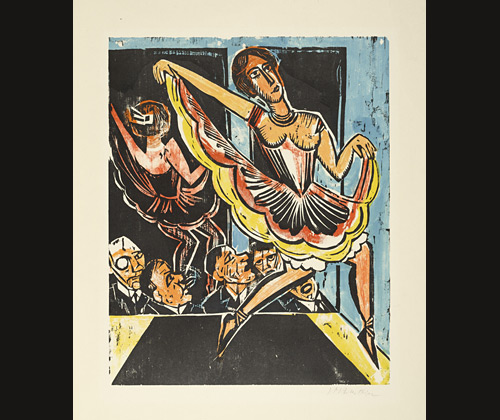

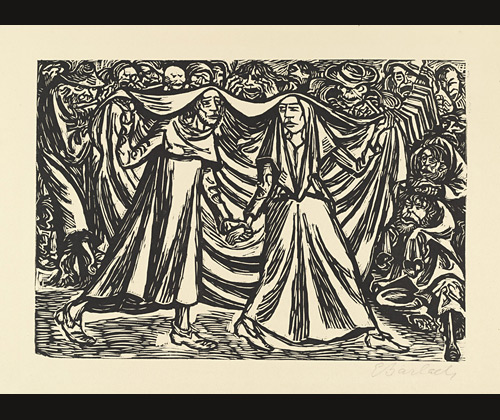

Fritz Zeymer

The Dancer Gertrude Barrison (plate 3) from the First Theater Program of Kabarett Fledermaus (Cabaret Fledermaus)

1907

This illustration captures the glittering, champagne-and-cocktail-fueled atmosphere of the Viennese nightclub where this dancer performed. Her flowing gown suggests freedom of movement, in stark contrast to the constricted clothing and social mores of the day.