A Lounge Chair for the End of the World

What still captivates us about the postwar designs of husband-and-wife team Charles and Ray Eames?

Rachael Schwabe

Sep 7, 2023

You’ve definitely met this lounge chair before. Its most classic form has two parts: a slightly reclined chair and a matching ottoman, both upholstered in leather and encased in a molded plywood shell. To look at this chair is to imagine yourself sinking into its plush, leathery surface. However you choose to sit—curled or splayed—this chair invites, even encourages, you to feel at ease.

The makers of the now iconic Lounge Chair from 1956 were the husband-and-wife team of Charles and Ray Eames. After meeting at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, they married in 1941, crystalizing a lifelong design partnership. To Ray Eames, “What works is better than what looks good. The ‘looks good’ can change, but what works, works.” The Eameses have played a foundational role in determining what “works” and what looks good, not only in furniture, but also in architecture, toys, and multimedia educational materials. The DNA of the Eameses’ designs endures in our ergonomic office chairs, in the fun colorways of the contemporary design firm HAY, and in human-centered approaches to home interiors.

So, what is it about Eames-designed furniture that has made it work for so many for so long—in other words, what makes an Eames an Eames? To find out, I spoke with staff from MoMA Design Store, the Museum’s Department of Architecture and Design, and the Eames Office.

Charles Eames, Ray Eames. Lounge Chair and Ottoman. 1956

Plywood experiments at Eames’s first California home, Richard Neutra’s Strathmore Apartments in Los Angeles. Featuring the Kazam! Machine and the molded-plywood mobile. 1941

Innovation with molded materials.

Before there was a Lounge Chair there was a leg splint. Upon moving to Los Angeles in 1941, the Eameses began experimenting with bent plywood, trying to exceed the innovations of their prize-winning design with Eero Saarinean for MoMA’s 1940 exhibition Organic Design in Home Furnishings. (Ray was not credited as an equal partner at this point in their careers.) The Eameses inventively put together slats of wood and a bicycle pump to create the “Kazaam! Machine”—a kind of curing oven that allowed them to form curved plywood shells in their apartment.1 Chay Costello, MoMA’s associate director of retail merchandising, likes the machine’s name for the way it “evokes the magician-like alakazam.”

They further refined their plywood-bending techniques when given the opportunity to make splints for wounded US Navy servicemen during World War II. The wood material was lighter and vibrated less than metal; it also didn’t transmit external temperatures to the wearer’s flesh. The splints led to stretchers and the nose cone of a plane. But Costello emphasizes that the real magic trick came later, as the splints foreshadowed furniture pieces like the LCW Chair in 1946. “You see the wood and you see the complex curves and the shape,” she said. “It’s so much nitty gritty, trial and error, but the end result is poetic.”

Charles and Ray Eames with Eames Side Chairs, in the 1960 Eames film Kaleidoscope Jazz Chairs

Softening home interiors with casual furniture and organic forms

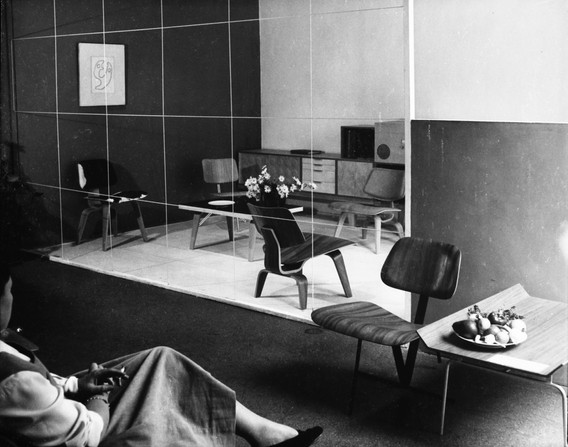

Like many designers working in the aftermath of World War II, the Eameses sought to use their designs to solve the problems of living. How can furniture meet the needs of their users in the broadest possible way? How might such items be made from quality materials while maintaining relative affordability for the middle class? These questions were publicly considered through efforts like MoMA’s Good Design exhibition series, held between 1950 and 1955.

To Eames Demetrios, director of the Eames Office, what sets Charles and Ray Eames apart from their contemporaries is the way “they equated being a designer with being a good host, one who anticipates the needs of their guests.” The Lounge Chair is perhaps the greatest ambassador for this philosophy. Both Amanda Forment, curatorial assistant in the Architecture and Design department, and Donald Koroh, MoMA Design Store manager, noticed how the Lounge Chair is low to the ground, making it easy to climb into and sit however you feel most comfortable. Kiyomi Higuchi, a product manager for MoMA Design Store, delightfully compared the chair’s upholstered leather sections to muffin tops. (She’s not wrong!)

Prior to the Lounge Chair, in 1948 the Eameses collaborated with the University of California, Los Angeles, to design a low-cost plastic chair shell for a competition-exhibition at MoMA.2 Higuchi observes that the throughline for these chairs is their continuous shape. “It’s like [the Eameses] took a person in a relaxed sitting position and put a chair around them.” Demetrios reminds us that the “profile” of a chair wasn’t their primary motivator. Rather, Charles and Ray were thinking through how the fabric would fit or the tension of the base of the chair. And they were constantly returning to their own designs, trying to solve a problem.

The Eameses’ emphasis on comfort and functionality extended to an argument for more casual home interiors. The Eameses seemed to give postwar middle- and upper-class individuals permission to soften the edges of geometric storage units with, as Forment put it, “objects that both define you and give meaning to your life.” Their Case Study House is a good example of this, on top of being, as Architecture and Design collection specialist Paul Galloway notes, a model for how to seamlessly integrate diverse objects into a home. To the Eameses, this ranged from ornaments to textiles to folk art from their global travels. Forment and I agree that it’s perhaps this quality that makes it so easy for Eames furniture pieces themselves to become a kind of cultural capital; your furniture is an extension of you.

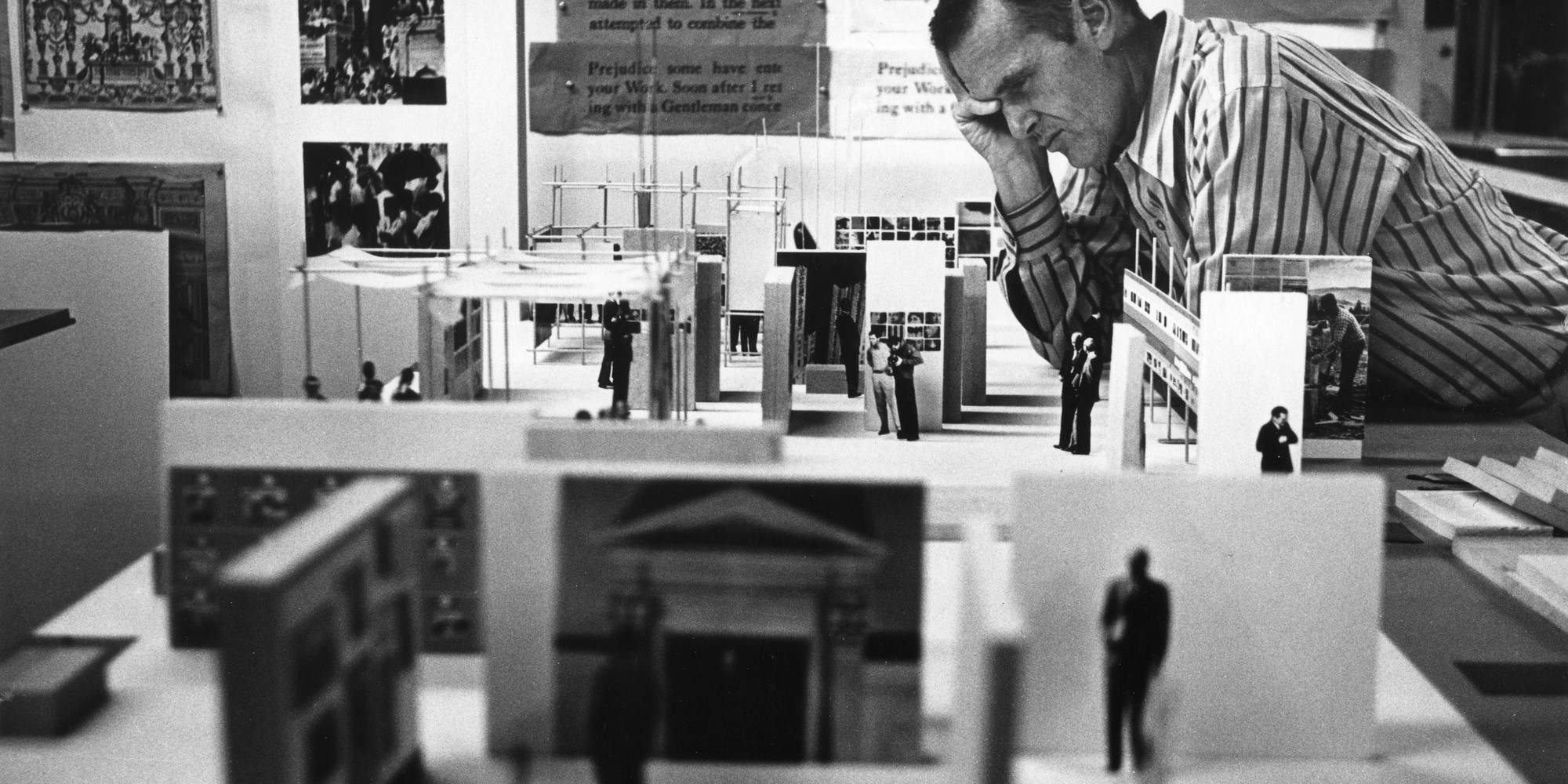

New Furniture Designed by Charles Eames 1946 MoMA exhibition

Herbert Matter’s son, Alexander “Pundy” Matter, on the Eames Molded Plywood Elephant in 1945

A sense of playfulness and delight in process and product

If the Eameses’ Case Study House signified anything for its inhabitants, it was the thorough entanglement of their creative collaboration. Ray Kaiser was a skilled abstract painter; Charles Eames trained as an architect-engineer. They were united by a shared enthusiasm to expand their repertoire of mediums.3 The Eameses played off each other to produce designs that, as Galloway observes, “play well with others.”

Each individual I spoke to underlined the playfulness present in the Eameses’ body of work. It’s the attention to detail in their furniture, like the wire-frame base on their plastic and fiberglass chairs that Galloway appreciates for the way it “recalls bicycles, suspension bridges, and a child’s game of cat’s cradle.” Higuchi is amazed that the Eameses used the same bent plywood of the Lounge Chair to configure an elephant. Even La Chaise, a swooping chaise longue, delightfully mimics the elegant curvatures of a calla lily. At a larger scale there are the influential films the Eameses produced, including The Power of Ten in 1977.

Not to mention their use of color and patterns! Koroh associates their bright, saturated palette with toys. To him, the skateboards available in MoMA Design Store feel like a natural fit because “if they were around now, they totally would have gone into skateboards or scooters.”

It’s impossible to overstate the reach and impact of the Eameses’ contributions, but Costello sums it up best. “We are living in the future that they planned for us,” she said. “They were so integral to the mid-century definition of Good Design: that it solves a problem, that it serves a purpose, that it's about materials and form, that it's democratic, it should be as affordable as it could be, and it belongs to everyone.” Put another way, the Eameses continue to play “host,” anticipating the needs of our contemporary moment.

Be sure to visit the MoMA Design Store’s Eames Office Pop-Up, and don’t miss A Talk about MoMA and the Eameses on Thursday, September 21, and the Chairs, Chairs, Everywhere! family art-making event on October 14.

-

Donald Albrecht, “Evolving Forms: A Photographic Essay of Eames Furniture, Prototypes, and Experiments,” in The Work of Charles and Ray Eames: A Legacy of Invention (New York: Harry N. Abrams in association with the Library of Congress and the Vitra Design Museum, 1997), 74.

-

Donald Albrecht, “Evolving Forms: A Photographic Essay of Eames Furniture, Prototypes, and Experiments,” 89.

-

Pat Kirkham, “Humanizing Modernism: The Crafts, ‘Functioning Decoration’ and the Eameses,” Journal of Design History 11, no. 1 (1998): 15-29.

Related articles

-

UNIQLO ArtSpeaks

Anna Burckhardt on Clara Porset’s Butaque Chair

A Cuban artist working in Mexico, Porset incorporated Mexican craft traditions into her signature design.

Nov 12, 2021

-

What Do We Mean By Good Design?

Ten objects from The Value of Good Design highlight the democratizing potential of design.

Juliet Kinchin, Andrew Gardner

Mar 4, 2019