The AI Brain in the Cultural Archive

What new artifacts emerge when we look at the next revolution in media?

Lev Manovich

Jul 21, 2023

We are currently living through early days of a major revolution in communication, media, and culture. Some have already compared it to the invention of photography, the Gutenberg printing press, or cinema. I think it’s too early to say how big this new revolution is; its true scale will become more clear in a few years. But what is it?

For decades we have assumed that AI will not be able to simulate that unique human ability: artistic creativity. Translating between languages, summarizing text, playing chess, and winning Go? Sure. But writing original music, generating detailed photographs of people and objects that do not exist, or making images that perfectly emulate the effects of any media and styles of thousands of well-known artists—and also synthesizing new styles and visual media from combinations of existing ones? All this would have been seen as impossible only five years ago. But in the past few years, AI scientists have given computers seemingly unique human abilities to create and imagine. If you are one of the millions of people who are using tools like ChatGPT, Midjourney, DALL-E, or MusicML, you have likely experienced mixed feelings of inspiration and fear, excitement and bewilderment, and maybe even anger at the newly emergent abilities of generative AI.

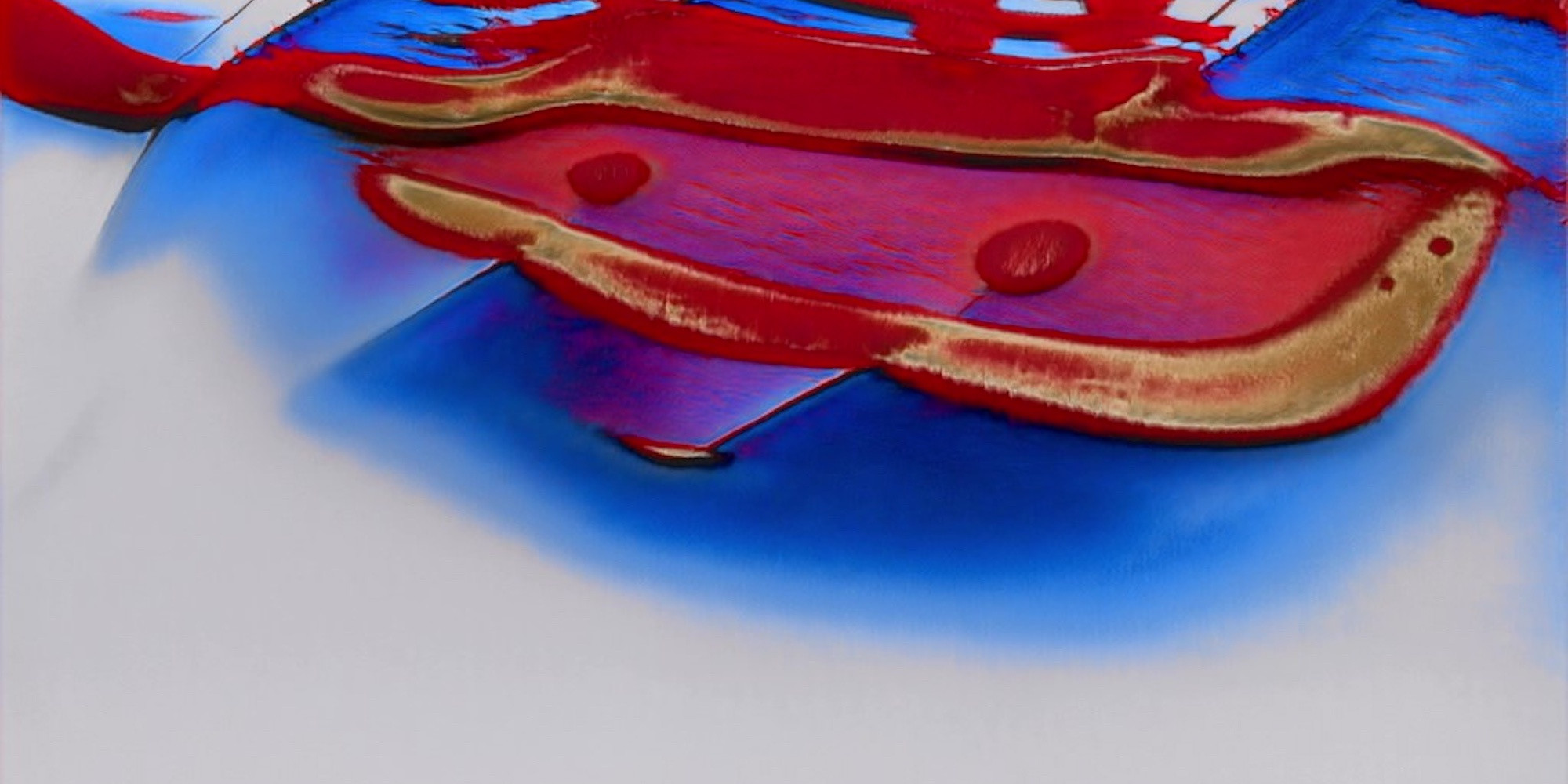

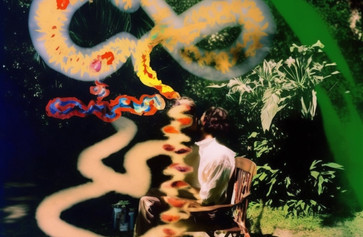

Creation. AI-generated images

At this point we know much more about human creativity and how it works than we do about “AI creativity.”

At this point we know much more about human creativity and how it works than we do about “AI creativity.” In philosophy, psychology, cognitive science, and other fields, many alternative theories and types of creativity have been proposed. With time, we are likely to see the same for “AI creativity.” But we are not at this point yet. After neural networks are trained on trillions of text pages or billions of images harvested from the Web, they can compose new texts and images. However, the abilities of the creative nets are not defined by traditional algorithms; instead, they are distributed among trillions of connections between billions of artificial neurons. In other words, we managed to create a technology that is in some ways similar to a human brain—and that is so complex we can’t understand how it works.

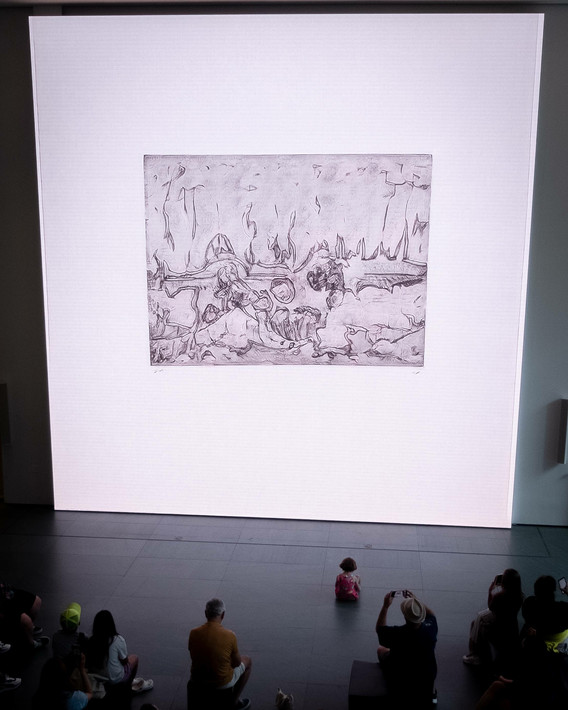

The current generation of creative AI systems have been trained on very large and heterogeneous collections. However, it’s equally interesting to limit the training data set to a particular area in the larger space of human cultural history. Unsupervised by Refik Anadol, currently on view at MoMA, is such an experiment. Its dataset is approximately 140,000 artworks in MoMA’s collection. This collection, in my eyes, represents one of the most creative and experimental periods in human visual history. It captures the feverish and relentless experiments of artists, designers, architects, and photographers to generate new visual and communication languages and—most importantly for these artists—to “make it new.”

At first glance, this logic of modernism is the opposite of the process behind creative AI. In many different times and very different places, modern artists wanted to break with traditional art and its key qualities such as visual symmetry or narrative content. Their creativity was based on a fundamental rejection of everything that came before—at least in theory, and as expressed by their manifestos. Deep neural networks, however, are trained in the opposite way: by learning from the historical past and all art created up until now. In a way, a neural network is like a “meta” conservative artist, studying in the virtual “museum without walls” that contains all human historical art.

Refik Anadol’s Unsupervised at MoMA

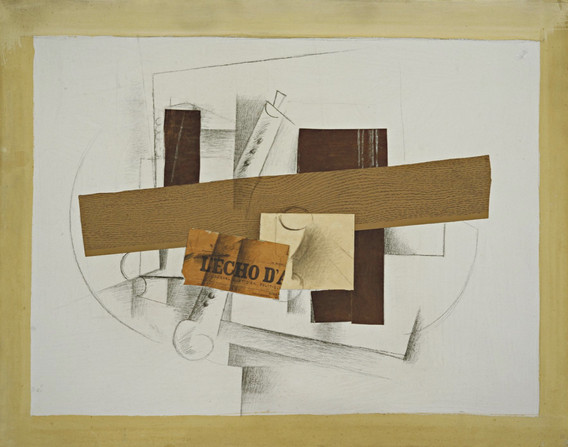

Georges Braque. Still Life with Tenora. 1913

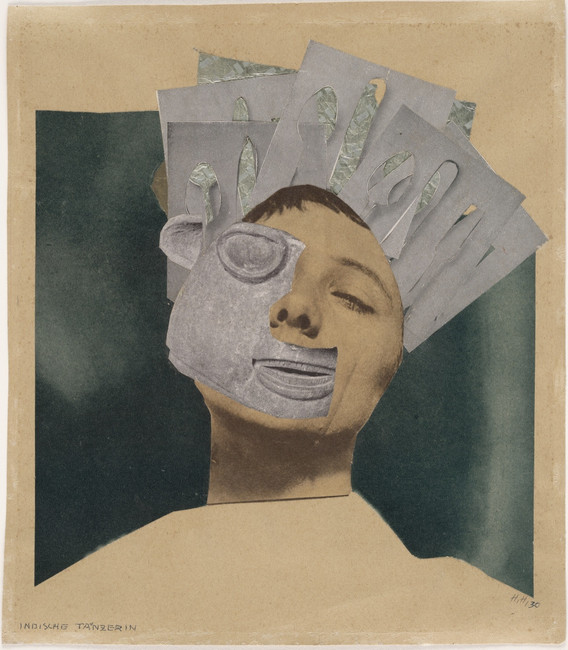

But we know very well that art theory and art practice are two different things. While Western modernism wanted to completely reject the past and everything that came before, it did not. Instead, many modernist artists began their careers by reinterpreting traditional Japanese prints (see Vincent van Gogh), African sculpture (Pablo Picasso), or Russian icons (Kazimir Malevich). While modernism’s overall emphasis was originality and newness, another procedure it developed in this search for novelty was, paradoxically, direct quotations from the universe of visual media that was rapidly expanding in the early 20th century. Large titles and the inclusion of photos and maps made newspapers more visually impactful; new visually oriented magazines such as Time and Vogue also debuted in this period. Responding to this visual turn in mass culture, in the early 1910s Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso started to incorporate fragments of newspapers, posters, wallpapers, or pieces of colorful fabrics in their paintings. A few years later, artists such as John Heartfield, George Grosz, Hannah Höch, Aleksandr Rodchenko, and others developed another method of using mass media images: photomontage.

Contemporary artworks that use neural networks trained on massive cultural databases, such as Anadol’s Unsupervised, stand in a long tradition of making new art from accumulations of images and other media. In this way, these artworks continue expanding possibilities of art and its methods, and especially “database art.”1 This expansion includes new methods for “reading” cultural databases. The double brain of Unsupervised’s creators (i.e., a human brain and an “artificial brain” of the neural net) does not directly quote from historical art or create media collages like earlier artists. Instead, the neural network extracts complex patterns and relations from hundreds of thousands of artworks and objects collected by MoMA. It then uses everything it learned to generate an endlessly changing visual field that interpolates between the features of these artworks and the relationships between them in unpredictable ways. The surface is constantly changing, oscillating between 2D and 3D, between pure abstraction and seemingly recognizable echoes of particular artworks, between gentle movements and dramatic visual explosions. These are not mechanical imitations or simulations of what already was created. In my opinion, they are genuinely new cultural artifacts with contents and styles that we have never seen before.

Looking at the work, I am reminded of the alien planet in Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Solaris (1972). Solaris synthesizes human-like “guests” from the memories of human inhabitants of the space station orbiting the planet. The surface of the planet changes throughout the film, sometimes showing concrete images, then starting to form islands. Unsupervised also generates something that is both very familiar and also alien, detached from all the thoughts and impulses of the artists who made works in MoMA’s collection. Perhaps it is an early glimpse of the new forms of consciousness that will emerge between the humans and computer systems they engineered—or a vision of a future language of culture, which we are just now learning how to read.

Hannah Höch. Indian Dancer: From an Ethnographic Museum (Indische Tänzerin: Aus einem ethnographischen Museum). 1930

Lev Manovich is a theorist of digital culture, an artist, and a writer. He is presidential professor at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, and a director of the Cultural Analytics Lab.

Related articles

-

Deep Learning: AI, Art History, and the Museum

Refik Anadol’s Unsupervised invites us to come to terms with new ways of making history at the edge of what’s technically possible.

Joan Kee, Michelle Kuo

Jun 15, 2023

-

Play with AI

The acclaimed writer and founder of Google’s Artists + Machine Intelligence program asks: What if we imagined a healing AI?

K Allado-McDowell

Mar 2, 2023