Introducing Frédéric Bruly Bouabré: World Unbound

Read an exclusive excerpt from the exhibition catalogue online.

Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi

Mar 15, 2022

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré is one of Africa’s best known and most celebrated 20th-century artists. Born in 1923 in the Bété village of Zéprégühé, near Daloa, the major city in west-central Côte d’Ivoire, Bouabré is celebrated for his untiring attempts to codify, archive, and share information that connects the human story. His singular devotion to drawing and his unwavering interest in taxonomy were remarkable, especially among African artists without academic training, but it was his approach to image and language, condensing oral culture into a dizzying multiplicity of visual forms and written annotations, that sets him apart. In the formative period of his career, Bouabré was concerned with transcribing the history and knowledge of his native Bété ethnic group, and he set out to create the first writing system for the Bété language in the 1950s. He referred to his pioneering syllabary as a Bété alphabet, and he created an artwork version, Alphabet Bété, in the early 1990s.

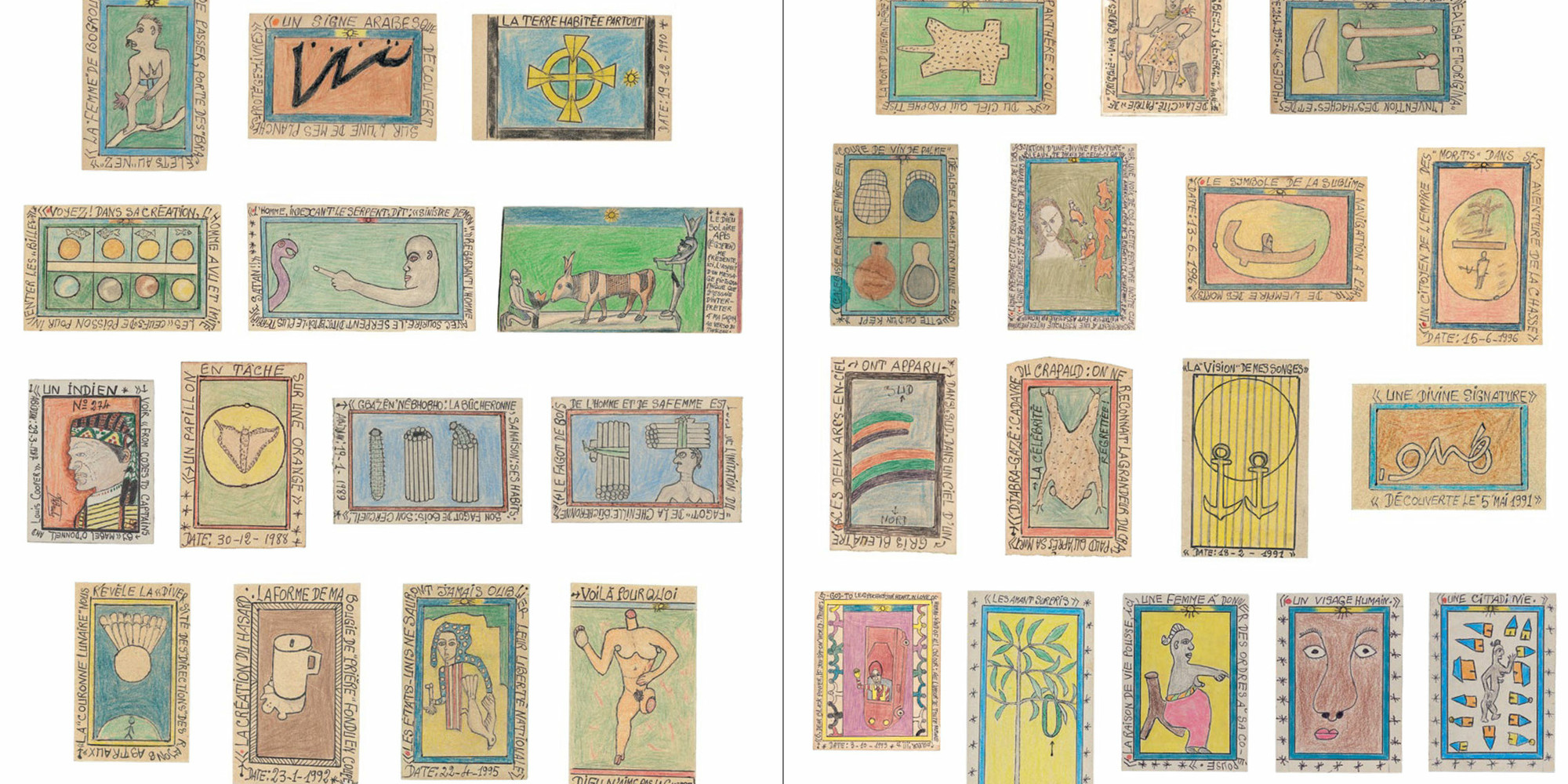

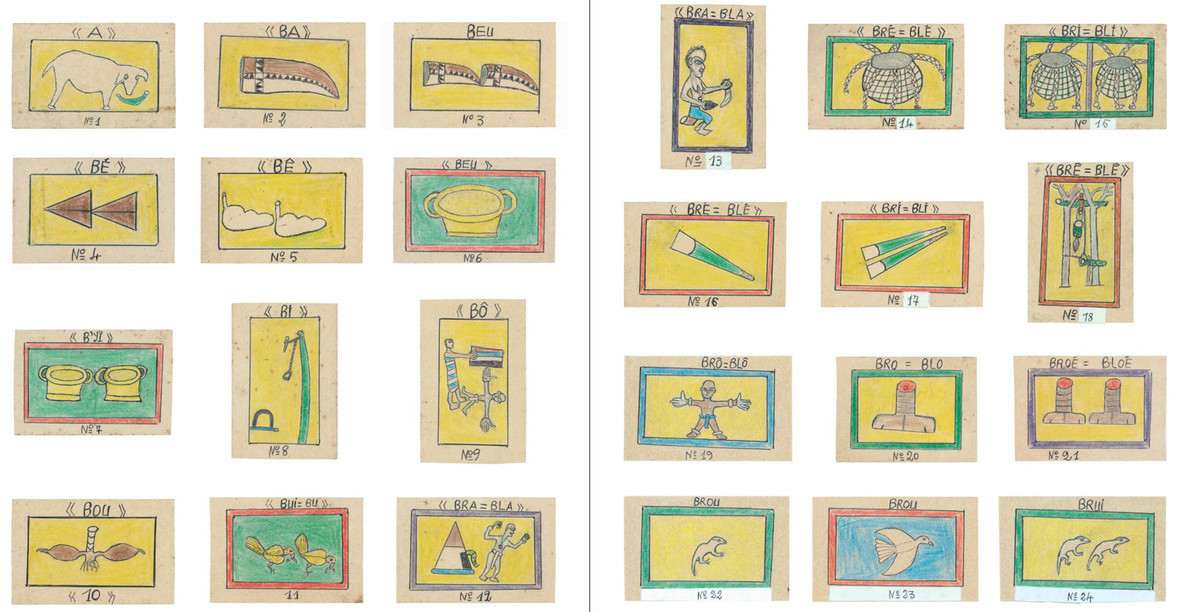

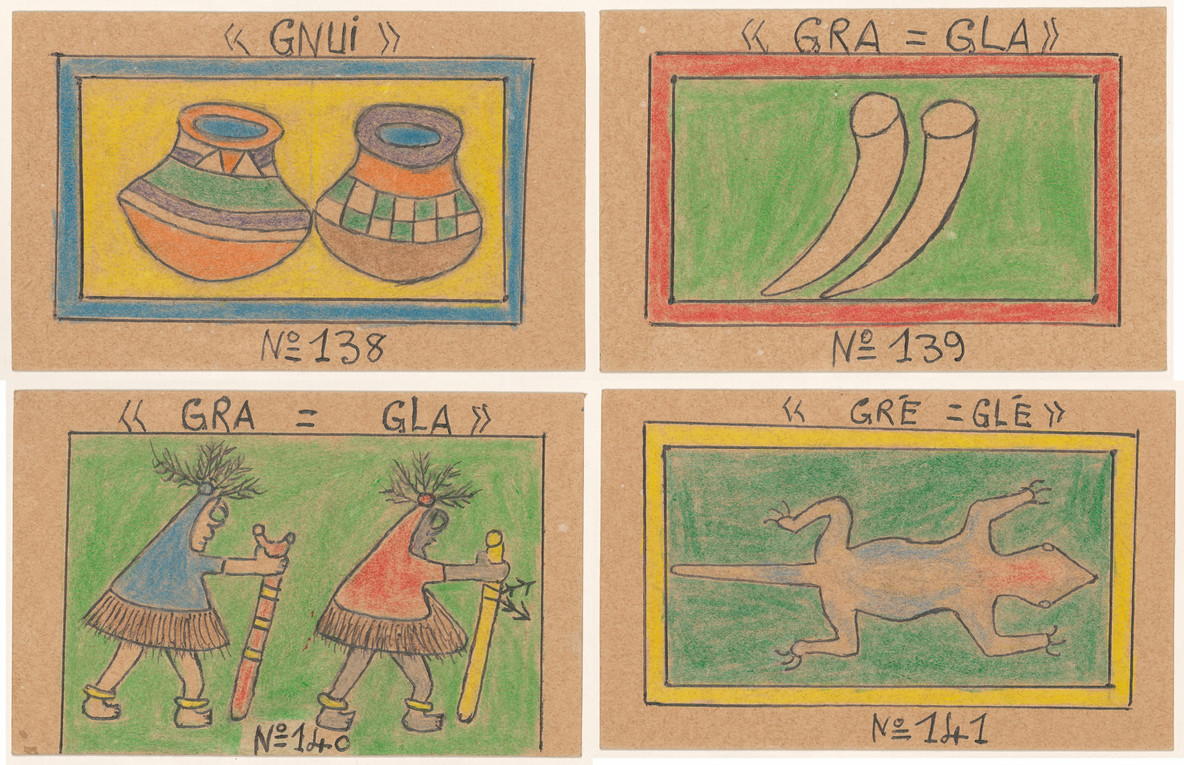

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré. Details from Alphabet Bété. 1990–91

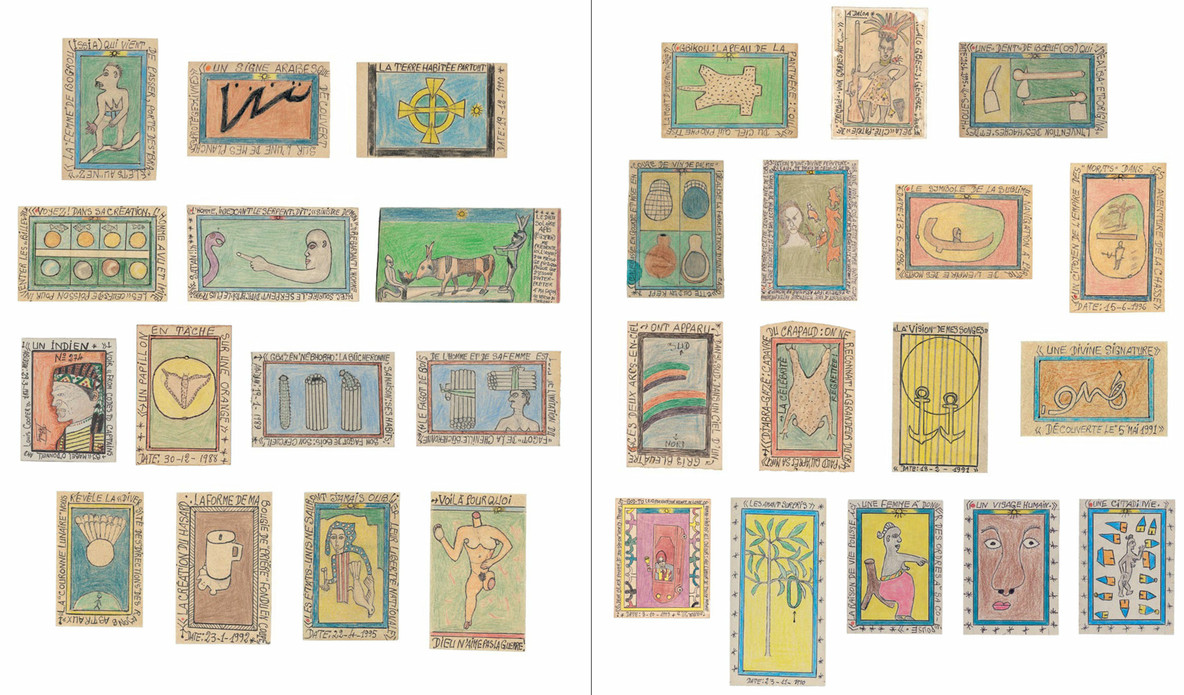

World Unbound, Bouabré’s first museum survey exhibition in North America, is anchored by Alphabet Bété and the multipart work Connaissance du monde (Knowledge of the World) (1987–2008), which are presented among other works that span the artist’s career from the late 1970s to his death in 2014. Alphabet Bété consists of 449 drawings executed in ballpoint pen, pencil, and colored pencil on small rectangular pieces of cardboard. The images depict everyday scenes of human activity as well as quotidian items such as fruit, farming tools, body parts, tadpoles, worms, and musical instruments, each of which is correlated to a single Bété monosyllable. Connaissance du monde, a selection of 30 drawings on cardboard made over 21 years, is an inventory of the artist’s observations, encompassing everything from the appearance of rainbows to the shapes taken by spilled candle wax to meditations on beauty, human rights, and liberty. In its breadth, the work both exemplifies Bouabré’s encyclopedic proclivity and symbolizes his oeuvre overall: all of the artist’s efforts were aimed at recording, analyzing, and transmitting his knowledge of the world.

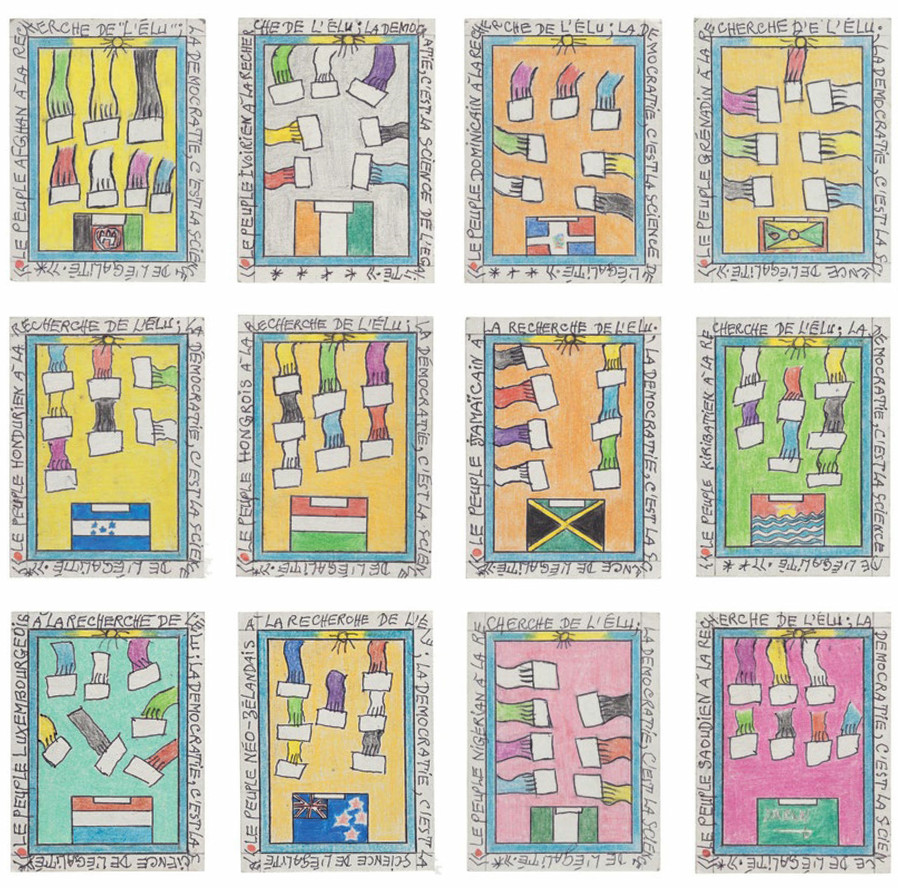

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré. Connaissance du monde (Knowledge of the World). 1987–2008

Bouabré traced this vocation back to a significant experience in his mid-twenties. On March 11, 1948, on his way to work, he experienced a celestial vision. As he later wrote, he was then reborn with a new identity and purpose: “Since the sky opened to my eyes and the seven colored suns described a circle of beauty around their ‘Mother-Sun,’ I am the one that must from now on be called ‘Cheik Nadro,’ the Revealer.”1 After this revelation—which he later depicted in an artwork titled Vision Divine (1991) featured in the exhibition—he applied himself to a search for divine truths in nature and to the interpretation of his immediate surroundings and of the world at large, first through writing and then through visual art. This origin story is central to the reception of Bouabré’s art, especially in the West, beginning with his participation in Magiciens de la terre (Magicians of the Earth), his first international exhibition, in Paris in 1989.

Since then, scholars and curators have addressed Bouabré as a poet, philosopher, thinker, ethnologist, folklorist, and draftsman on the strength of his oeuvre overall, yet simultaneously have referred to his artwork as outsider art or categorized it as art brut.2 The 1948 vision was undoubtedly a pivotal event in Bouabré’s life, and it shaped the artist he became. Yet an emphasis on the primal or the uncanny obscures the complex sequence of events that led to his art making and distracts from a formal investigation of his process-based approach. Bouabré relied more on the powers of observation and imitation than on psychic revelation, contrary to what many writers on his work have emphasized. “I do not work from my imagination,” he stated. “I observe, and what I see delights me. And so I want to imitate.”3

In introducing Bouabré to an audience that may be unfamiliar with his art, this publication and the exhibition it accompanies aim to provide a fuller picture of his life and work, exploring the confluence of events and varied life experiences that eventually led to his artistic career. Bouabré’s deep immersion in the worldview and knowledge system of the Bété in his youth and his several decades spent in the civil service in the colonial and early postcolonial periods (during which he worked with Western ethnographers and anthropologists) cohered with a lifelong devotion to knowledge and found an outlet in his art. Stylistically, Bouabré’s art may initially appear amateurish, but it is highly sophisticated in its marriage of image and text, a combination he perfected over many decades. Bouabré used writing “to explain what I’ve drawn,” he said. “Writing is what immortalizes. Writing fights against forgetting.”4 But this explanation does not begin to capture the full extent of the conceptual stakes inherent in his work. His practice was sparked by the invention of his Bété syllabary, which began as a process of translation from speech to image and then to text—a cycle of linguistic transformation that is unique to Bouabré’s oeuvre.

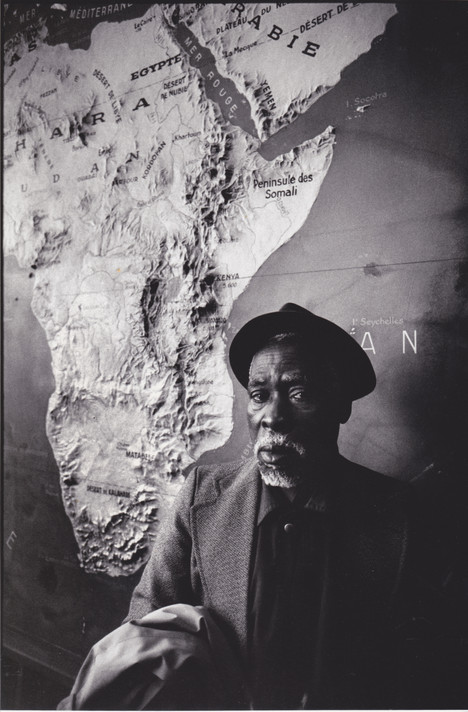

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré at the Musée de l’Homme, Paris, 1993

Details from Alphabet Bété. 1990–91

In the 1970s Bouabré began making drawings to accompany stories inspired by Bété folktales and proverbs. Semence de la vie (Seed of Life) (1977) may be his earliest known artwork. The drawings, which he referred to as tableaux—each measuring around 12 by eight inches and executed with ballpoint pen, pencil, and colored pencil—explore the origin of life, incorporating Bété allegorical tales and other fictional sources. In the 1980s Bouabré continued his examination of Bété culture and history, creating ongoing bodies of work that can be presented partially or as complete series. Mythologie Bété (1987–88), a selection of 19 drawings, portrays scenes from Bété folktales, while Civilisation Bété (1988) comprises 27 drawings of domestic implements, farming tools, and musical instruments, offering a survey of Bété material culture.

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré. Details from La démocratie c’est la science de l’égalité (Democracy Is the Science of Equality). 2010–11

Bouabré enlarged on his themes or took them in new directions in the 1990s and 2000s. Hommage aux femmes du monde (Homage to the Women of the World) (2007), a finite series of 200 drawings of women draped in various national flags, celebrates both women’s rights and women’s role as pillars of nation building. Ever the chronicler, during the political crisis in Côte d’Ivoire around the controversial 2010–11 presidential elections, Bouabré made 182 drawings depicting hands of many colors casting ballots into boxes bearing the national flags of various countries, presenting democracy as a universal ideal. Both works demonstrate Bouabré’s brilliance in simultaneously addressing the local and the global, reflecting both personal and universal experience. A consummate visionary, Bouabré was not constrained by time or place or culture. Beginning with his own Bété culture, he expanded his gaze outward to encompass the entirety of the human experience, sharing, through his nearly four-decade career, his idiosyncratic understanding of our common bond.

Want to read more? Explore the whole catalogue.

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré: World Unbound, organized by Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi, The Steven and Lisa Tananbaum Curator, with Erica DiBenedetto, Curatorial Assistant, and with support from Damasia Lacroze, Department Assistant, Department of Painting and Sculpture, is on view March 13–August 13, 2022.

-

Bouabré, On ne compte pas les étoiles (Saint-Jean-d’Angély, France: Éditions Bordessoules, 1989), 51. Translation by Jeanine Herman.

-

For example, art historian Robert Farris Thompson described Bouabré as a “remote genius” whose art emerged from the recess of dreams and the unconscious. Similarly, curator Sarah Lombardi wrote that Bouabré’s art “reveals the full details of the creative rerouting and reclaiming process that underlies Art Brut in general, and to which such creators in particular tend to resort.” Thompson, “Scripts of the Spirit: Frédéric Bruly Bouabré,” in Robert Lehman Lectures on Contemporary Art, vol. 2, ed. Lynne Cooke, Karen Kelly, and Bettina Funcke (New York: Dia Foundation, 2004), 82; Lombardi, “Frédéric Bruly Bouabré: Self-Taught Encyclopaedist,” Raw Vision, no. 69 (Summer 2010): 45.

-

Bouabré, interview by Yaya Savané, in Big City: Artists from Africa, exh. cat. (London: Serpentine Gallery, 1995), 9.

-

Bouabré, in the film Frédéric Bruly Bouabré: L’universaliste, directed by Andres Alvarez and Philippe Lespinasse (Lausanne: Collection de l’Art Brut; Le Tourne, France: Lokomotiv Films, 2010). Translation by the author.

Related articles

-

UNIQLO ArtSpeaks

Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi on Sue Williamson

Williamson’s 49-panel work captures the legacy of South African apartheid through one man’s life.

Dec 18, 2020

-

Playlist

The FESTAC ’77 Mixtape

Sample the sonic world of the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture.

Ntone Edjabe, Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi

Dec 9, 2020