Remembering Lawrence Weiner, 1942–2021

We pay tribute to an artist whose expansive work demonstrated that art has no bounds.

Christophe Cherix

Dec 7, 2021

I discovered Lawrence Weiner through books—not his exhibition catalogues, but the publications edited by the gallerist-turned-publisher Seth Siegelaub. Having little taste for “the shopkeeper aspect” of owning a gallery, Siegelaub shut down his exhibition space in 1966 and, a couple of years later, began asking artists to make work destined for the pages of books, as opposed to the walls of a white cube. Seth and Lawrence—born a year apart—attended the same New York high school, Stuyvesant, but met each other a few years later, in 1963. The following year, Siegelaub started showing Weiner’s work, including shaped canvases and small propeller paintings, in his short-lived gallery. And when Seth made the leap into Conceptual art, Lawrence’s work was also very much on his mind.

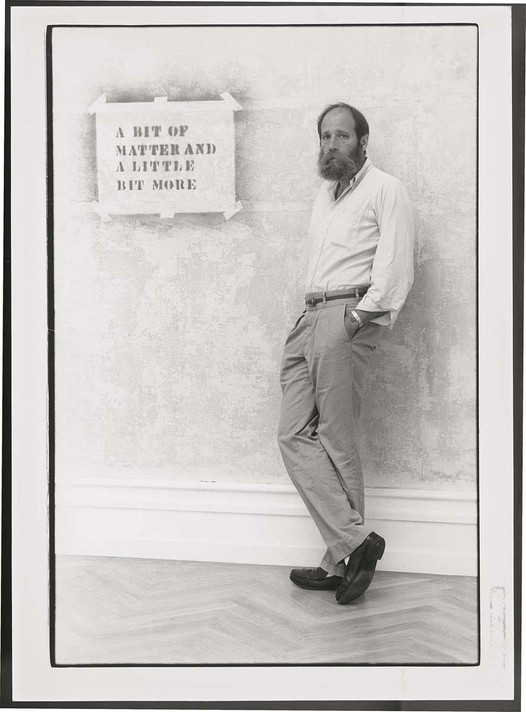

Lawrence Weiner in front of A BIT OF MATTER AND A LITTLE BIT MORE (1976), Kunsthalle Bern, Works & Reconstructions, August 19–October 16, 1983

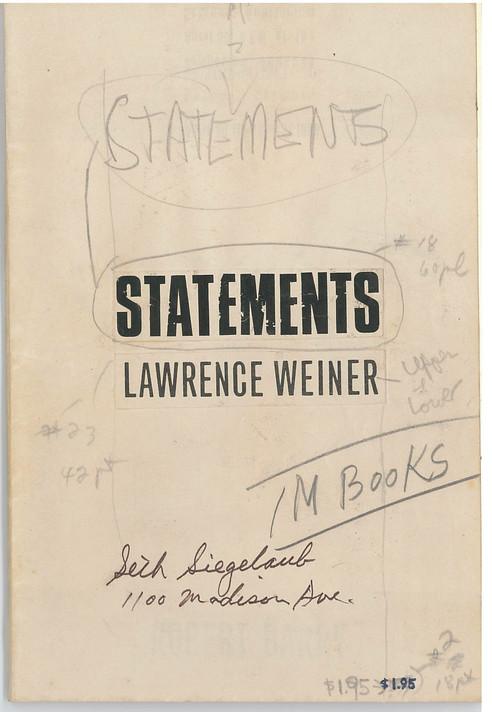

I can’t remember the precise date and place of my first meeting with Lawrence. His art and his person have become, for me, inseparable. I do, however, remember the day, during the fall of 1992, when I opened his first book Statements, published by Siegelaub in December 1968. Still an art history undergraduate, I traveled from my birthplace, Geneva, Switzerland, to New York hoping to see a copy in MoMA’s Library. I recall browsing its pages—under the benevolent yet watchful eye of Clive Philpott, the Library’s then chief librarian—while the book literally fell apart in my hands. The small volume, cheaply printed at 1,000 copies, had not been made to last. My considerable excitement was accompanied by the horrifying impression that the book would self-destruct if I kept looking at it. Seth later told me that it had been very much his and Siegelaub’s intention “to produce the books as simply, as directly, and as inexpensively as possible and to distribute them as widely as possible.” Never had they wished for them to enter the rare book market or, for that matter, the Museum of Modern Art.

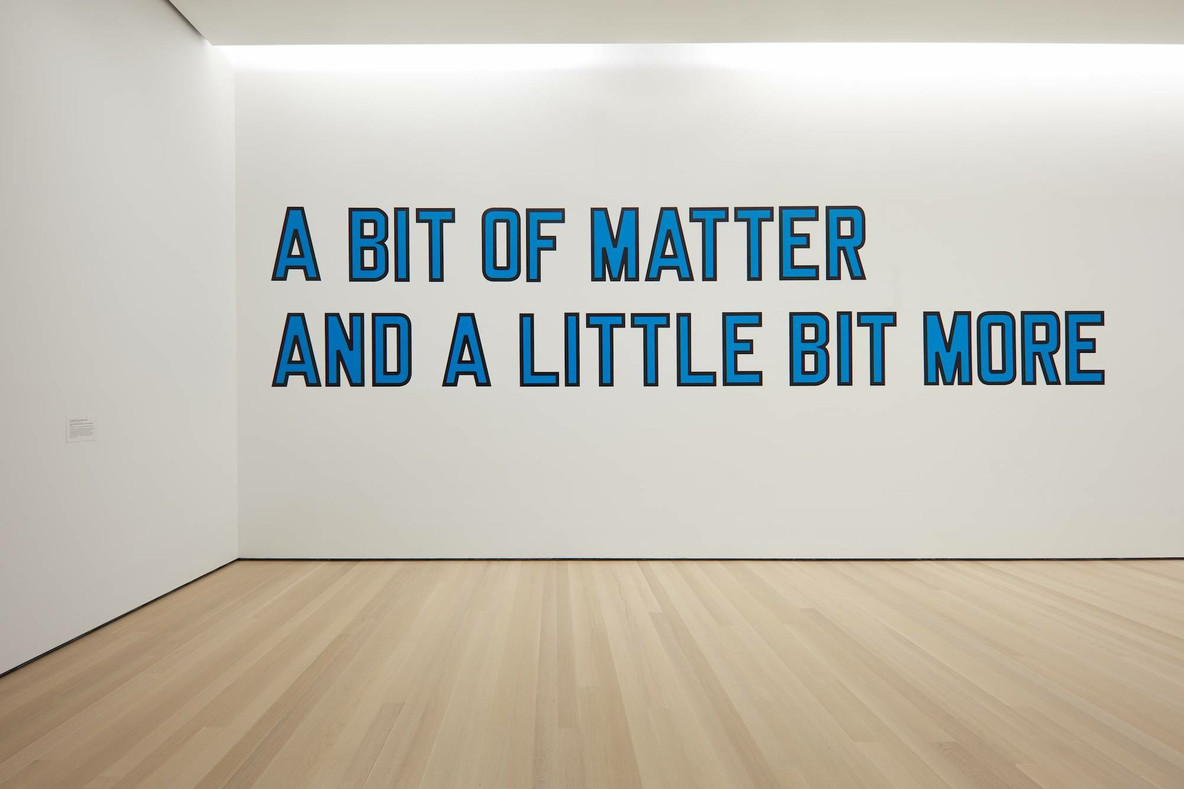

Fifteen years later, I joined MoMA. And there I had the privilege to acquire many extraordinary works by Weiner, with the support of some of his earliest advocates—Seth himself, Adriaan van Ravesteijn, the cofounder of Art & Project in Amsterdam, and Herman Daled, who built in Brussels one of the most remarkable collections of Conceptual art—while regularly installing his “pieces” on the Museum’s walls. I learned a great deal from colleagues who shared my interest in Lawrence’s work, particularly Kynaston McShine, who showed him at MoMA as early as 1970, as part of Information, McShine’s landmark survey of Conceptual art. It was almost 50 years later, for MoMA’s reopening in the fall of 2019, that a work by Weiner was last added to our galleries—and it remains on view today. It felt like a fitting tribute to select one of his pieces for the beginning of our mid-20th-century galleries. The work, made in 1976, had come to us with the Daled Collection in 2011, but it had been part of the Museum’s history for much longer. It simply reads:

Maquette for cover of Lawrence Weiner’s Statements. 1968

Lawrence Weiner. A BIT OF MATTER AND A LITTLE BIT MORE. 1976. Installation view, The Museum of Modern Art, October 21, 2019–ongoing

Weiner had shown A BIT OF MATTER AND A LITTLE BIT MORE, in the year of its making, on the entrance door of PS1 when the art center opened in Long Island City. In all the intervening years—during which MoMA and PS1 became one institution—it remained on view. As a result, today the same work, installed by the artist in very different ways 43 years apart, welcomes visitors both in Queens and Manhattan.

Despite the apparent simplicity of his work, Lawrence made revolutionary contributions to the art of his time. Among them is the capacity for a piece to simultaneously exist in multiple locations, while each time completely changing form according to its context of presentation. For Weiner, art is not bound to a support—wall, piece of canvas, video, computer screen, or sheet of paper. It is not the materials but the “little bit more” that makes all the difference. And each time I install one of his works, it’s the image of the pages of Statements scattered in front of me that comes back to my mind. The panicked feeling is, thankfully, gone, but the excitement of experiencing a great work of art remains. Weiner taught me that art cannot be confined in even the most beautiful book. For this, I’ll always be grateful.

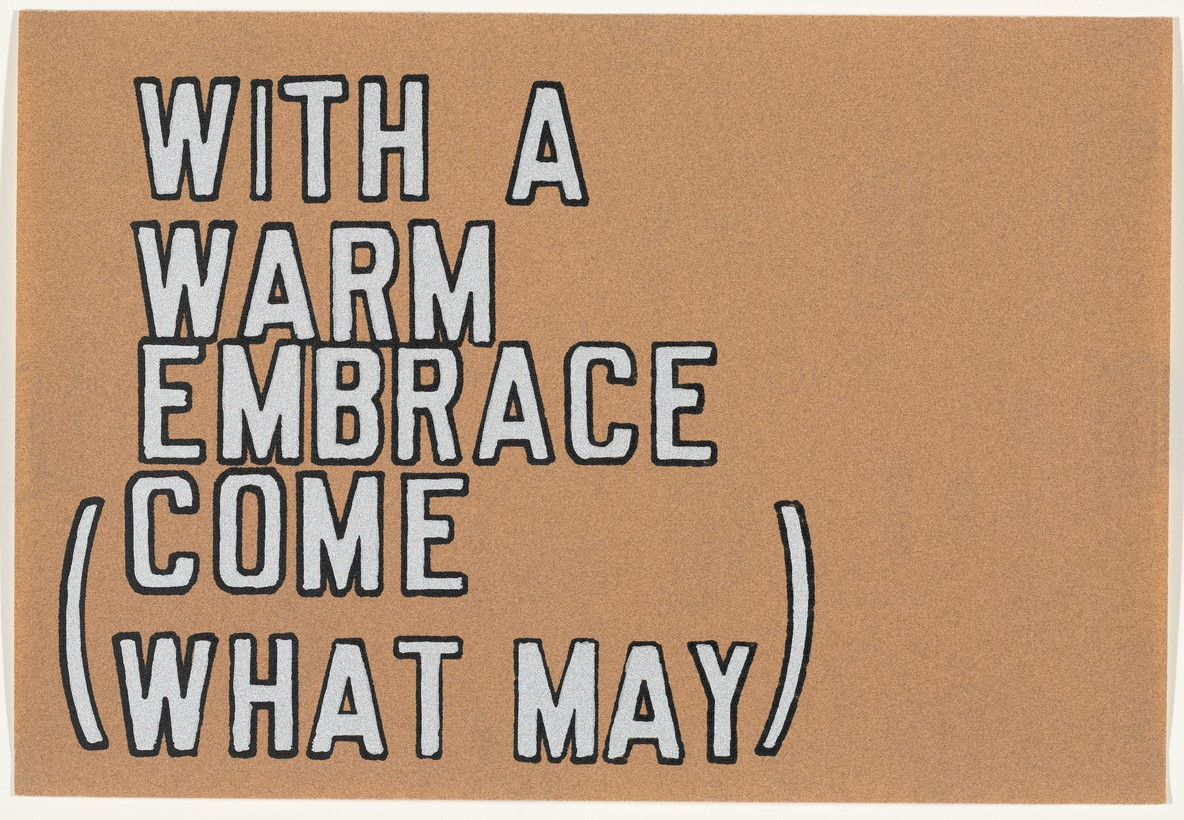

Lawrence Weiner. With a Warm Embrace (Come What May). 1995

Related articles

-

Tribute

Remembering Herman Daled, 1930–2020

Artists recall the late collector’s support and deep appreciation for “objects of knowledge.”

Lawrence Weiner, R. H. Quaytman, Dan Graham, Hans Haacke, Christophe Cherix

Jan 6, 2021

-

50 Years Later, a Conceptual Art Exhibition Still Courts Controversy

Lucy Lippard, Lawrence Weiner, Mel Bochner, Paola Antonelli, and the late Kynaston McShine reflect on Information, one of the most influential exhibitions of the 20th century.

Lawrence Weiner, Mel Bochner, Lucy Lippard, Paola Antonelli, Kynaston McShine, Hanna Girma

Jan 28, 2020