How Do We Build a Better Future?

Architects Felecia Davis and Mario Gooden envision Black futurity through histories of resistance and mutual aid.

Arlette Hernandez

May 13, 2021

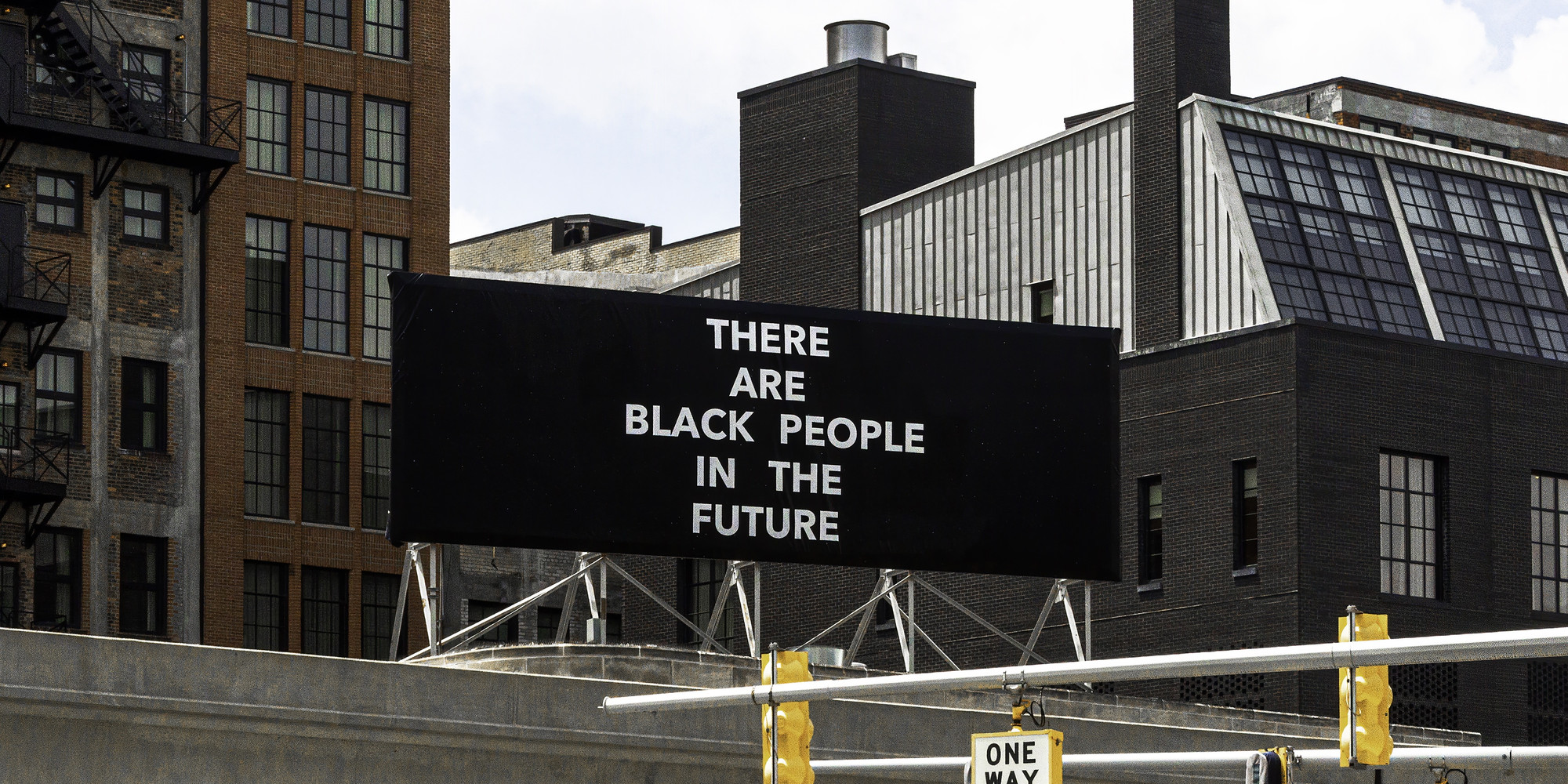

In March of 2018, artist Alisha B. Wormsley erected a billboard in Pittsburgh’s East Liberty neighborhood, which, like many Black and brown communities across the United States, has been afflicted by redevelopment and gentrification. The billboard’s message was clear, with white text on a black background declaring, “THERE ARE BLACK PEOPLE IN THE FUTURE.”

Explaining the origins of her installation, Wormsley writes, “It started out as a Black nerd sci-fi joke. A response to the absence of non-white faces in science fiction films and TV.” But the billboard’s meaning goes even further, reflecting the sentiments of musician Gabriel Teodros: “If we don’t write ourselves into the future, we get written out of tomorrow as well.”

Wormsley’s billboard, like each of the projects in Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America, is an intervention into the built environment and the narratives that erase the presence of Black people. These works—along with many of the others featured in our new online course Reimagining Blackness and Architecture—remind and show us that we can build a future that respects, celebrates, and uplifts Black people.

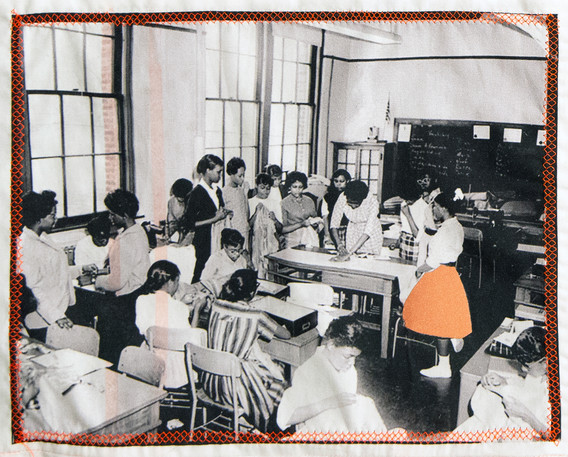

Felecia Davis. Fabricating Networks Quilt (detail: women in sewing class). 2020

Like Wormsley, architect Felecia Davis roots her work in the history of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, paying particular attention to the ways city and state governments have treated Black communities as “toolkits for racial discrimination.”

Located to the east of downtown Pittsburgh, the Hill District began as a vibrant neighborhood for Black residents and immigrants, as well as an active hub for business, theater, and music. Despite its rich history as a “Crossroads of the World,” the Hill District was ultimately marked for urban renewal, or large-scale redevelopment efforts initiated by the city to “revitalize” the area and remedy “decay.”

No matter the framing, urban renewal necessitates the disruption of entire communities. In the mid-1960s, the Hill District was cleared to make space for an interstate road and Civic Center, efforts that destroyed over 400 businesses and displaced more than 8,000 individuals from their homes. Today the area is little more than a parking lot, following the demolition of the Civic Center in 2012.

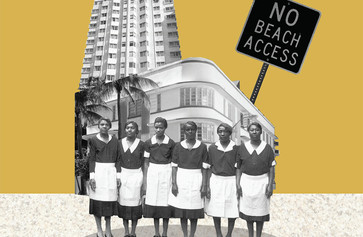

Installation view of Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America

Davis’s Fabricating Networks: Transmissions and Receptions from Pittsburgh’s Hill District responds to this history. The project consists of two parts, each an embodiment of what Davis calls a “computational textile,” or a textile that can communicate information by “sens[ing] and respond[ing] to bodies or to the environment.”

One of these textiles appears as a “black flower” with 34 robotically knitted cones embedded with copper threads. Functioning as an antenna, this black flower captures and amplifies sounds from MoMA’s galleries. The other textile featured in the project is a “touch-activated quilt with attached speakers.” Displayed on its surface panels are photographs taken in the Hill District during the 1950s and 1960s, many created by the photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris. In the future, Davis plans to take the quilt into the Hill District community, inviting residents to add their own panels and record their own stories.

Using technology as “a connector and communicator,” Fabricating Networks envisions new forms of collectivity and mutual aid that “transcend the boundaries that are meant to keep us contained.” For Davis, this project is “an opportunity to reimagine, to dream a new world order.”

During the 1960s, Nashville, Tennessee, was the site of many student-led sit-ins, marches, and protests that helped expand the civil rights movement nationwide. The city became both backdrop and stage for these events, which shaped the ways citizens are seen and heard. But Nasvhille’s legacy of resistance goes back even further.

Taking the form of a trolley, Mario Gooden’s project The Refusal of Space is inspired by Nashville’s first Black-owned streetcar line. Founded in 1905, the Union Transportation Company represented one of the ways in which the city’s Black citizens boycotted the Nashville Transit Company’s policy of segregation. Though that trolley system offered limited mobility throughout the city, for Gooden, it represents an important moment in the legacy of Black people demanding freedom through making and occupying space.

Referred to as a “protest machine,” The Refusal of Space explores the ways “Black people have made liberation a spatial practice throughout their existence across America.” The concept of liberation as a spatial practice is grounded by the work’s scale. Gooden explains: “This full-scale construction is meant to occupy space such that you can move around it and really get a sense of what it means to take up space and to make yourself feel present in resistance to those forces around you.”

With technology and textiles, through the movements of our bodies and the vibrations of our voices, Davis and Gooden envision a future for Black folks.

Incorporated into the trolley’s construction is image, sound, video footage, animations, and textiles, all of which combine to visualize the experiences of protestors from the Civil Rights era to the Black Lives Matter movement. Among the images included on and within the structure are scenes of protestors reclaiming the city’s streets through their marching and holding hands in front of the city’s police department as they fill the air with song.

Gooden argues that in architecture, Black people are either “invisible” or treated as “an object of desire and derision,” without having any desires of their own. Pushing back against conventional notions of architecture that restrict and minimize the presence of Black people, The Refusal of Space suggests “the ways in which Black people have moved through space, negotiated the barriers of social, political, and economic landscapes, and reformulated spatial conditions [while] improvising new ways of being.”

With technology and textiles, through the movements of our bodies and the vibrations of our voices, Davis and Gooden envision a future for Black folks. Their projects boldly proclaim that we will not be written out of tomorrow. Instead, we will continue to shape today, just how we have shaped yesterday and all the days before that.

Installation view of Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America

Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America is on view through May 31. You can now enroll in MoMA’s new online course, Reimagining Blackness and Architecture. Through original films, audio interviews, and short readings, the course will introduce learners to the ways in which Black artists, architects, scholars, and writers have responded to these histories of violence and exclusion to create new ways of being, reimagining the spaces that have refused us.

The exhibition is made possible by Allianz, MoMA’s partner for design and innovation.

Volkswagen of America is proud to be MoMA’s lead partner of education.

MoMA Audio is supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Related articles

-

Reconstructions

How Can Imagination Empower People?

Architects Germane Barnes and Walter J. Hood share projects that envision possible futures and collective spaces.

Arlette Hernandez

Mar 11, 2021

-

Reconstructions

Manifesting Statement of the Black Reconstruction Collective

Read an excerpt from the catalogue for the MoMA exhibition Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America.

Feb 24, 2021