Archival Repair: Shaping Collective History as Collective Future

Prompted by Garrett Bradley’s film America, the teams behind a series of MoMA and Studio Museum in Harlem workshops reflect on what they learned along the way.

Isabelle Hui Saldaña

May 5, 2021

During Memories for the Future: Garrett Bradley, Trevor Mathison, and Tina Campt in Conversation, Mathison, composer and founding member of Black Audio Film Collective, reminded us that archives must not only be consistently filled, but also regularly revisited and examined to surface gaps and unnoticed areas. The evening’s speakers emphasized the immense value of having everyday people involved in both the contribution and review processes.

Archives, when defined in the most traditional sense, are places where documents of history are held and made publicly available. The collection and distribution of these materials has historically been mediated by institutions. When the state and other institutions determine what is worth archiving, distrust becomes a barrier for marginalized people—especially given the devaluation of our contributions and personhood and the brutal mistreatment we’ve faced that archives document and erase. This is a challenge that many in the global Black radical tradition have risen to meet, creating blueprints for others to tear down barriers to access by forging pathways forward into the places where archives have been held, and by documenting their existences with whatever resources are available in order to fill the gaps in representation.

However, a question remains: How can we continue to expand the opportunity to be involved in the work of archival repair to all who may want it?

Memories for the Future tried to answer exactly that. Bradley, Mathison, and Campt’s conversation was the culmination of a three-month workshop series, which was the first major cross-institutional education and public programs collaboration between The Museum of Modern Art and The Studio Museum in Harlem.

Memories for the Future was created in conjunction with the collaborative exhibition Projects: Garrett Bradley, which featured the multichannel video installation America (2019). Drawing from Bradley’s process of reimagining lost histories of Black and racially integrated filmmaking from the early 20th century, Memories for the Future connected over 650 adult and teen participants from across New York City and around the globe. Together, we considered how everyday memories and forgotten histories could be preserved and brought into the future using visual and sonic forms.

The invitation to “make a memory for the future” by creating a short film that re-remembered a moment, object, or person that was lost was central across public and community partner workshops, artist discussion sessions, and digital resources. Participants were encouraged to use this project to transform a loss or absence in their life into something they could share with others and bring into the future.

During the culminating conversation, Black feminist scholar of visuality Tina Campt illuminated that what America and Memories for the Future sought to do, in tandem, was provide access to inspiration, resources, and facilitation; allow for the agency to choose whether and how to begin a reparative relationship with archives; and, most importantly, provide the belief that personal acts of repair were actually possible.

Daonne Huff, director of Public Programs at The Studio Museum in Harlem, described the collaborative series as a gift—both from the museums to our communities, and from our audiences to each other and to the museums. She shared that “in the midst of a year of tremendous loss, pain, absence, and longing, we also experienced recovery, hope, care, and connections within hyperlocal and digital realms in ways we couldn’t have fathomed. We saw this as an opportunity to empower people to process the intangible and give it visual and sonic form. This is a timely moment to reflect on what we leave behind and what we must hold onto as we move into an immensely unknown new world.”

America. 2019. USA. Directed by Garrett Bradley

Artwork as Prompt, Artist as Advocate

A key component of Memories for the Future was creating points of contact between artists and audiences in order to make the project of archival repair feel personal and accessible. In one of her many direct engagements with audiences, Bradley met with alumni of The Studio Museum’s Museum Education Practicum (MEP), a multidisciplinary, intergenerational group of arts workers and cultural producers of color. Approaching art education from positions as artists, curators, public school teachers, and educational programmers, they spoke to Bradley about her investment in education, asking why it was so crucial to center programming alongside the exhibition. Ilk Yasha, Studio Museum Institute coordinator, described this session as “an impactful convening of educators,” noting that “many exhibitions and artworks still don’t necessarily have education embedded at their core.”

Throughout this session, Bradley repeatedly emphasized, “America is a prompt.” Rather than simply existing for the purpose of viewing and thinking, America was intended to call forth others to take on the project of imagining a history where their stories were represented—and then bringing that imagination into physical form. For Bradley, a major component of making that possible was ensuring that knowledge and resources were shared widely.

Bradley and I worked together to create a DIY-Guide that took the prompt of America further, in order to support those who might want to answer its call. Yasha indicated that “the fact that *America*’s programming included a DIY guide was central to the session’s conversation,” in which arts educators considered the question, “What changes when an artist has a passion for education and is involved in the intellectual aspect of creating those elements in addition to the artwork?”

He concluded that an artist’s passion allows for the manifestation of programming that truly “complements the artwork… [and feels] like an extension of the artist’s original intentions, which, in this case, mirrors the purpose of the MoMA and Studio Museum education and public programs departments.”

Shanta Lawson, director of Education at The Studio Museum, shares Yasha’s perspective, relaying, “Our focus is on centering and making space for young people to learn and grow through experiences with art and artists,” and Bradley’s advocacy mirrored that call for young people to be fully integrated into arts programming.

Screenshot from Museum Education Practicum Alumni Session with Garrett Bradley, February 25, 2021

Inspired by Bradley’s eagerness to instill the value of our capacity for storytelling for youth audiences, Memories for the Future forefronted workshops for school-age students and teens. Each of these workshops included direct artist engagements to supplement the access to resources and facilitated spaces for exploration.

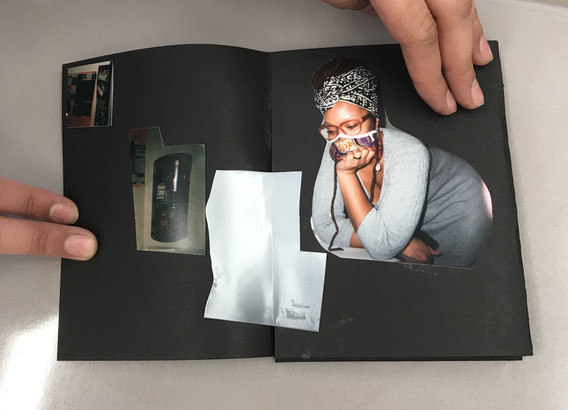

Both alumni and current members of The Studio Museum’s Teen Leadership Council and MoMA Teens cohorts collaborated in a three-week, hands-on workshop series discussing America, learning about archives and filmmaking, and creating new work.

Before beginning to engage with America’s reparative prompt, workshop leaders Ginny Huo, Rachell Morillo, and Amara Thomas wanted to make the specific role of a museum archive less opaque for the teen cohort. In a virtual visit with archivist Mimi Lester, who manages the collections databases and archives at The Studio Museum, Lester explained the operations and function of a museum archive. Additional activities, such as creating mood boards from images of loved ones and exploring filmmaking through social media apps, became entry points for the teens to start thinking about how they could contribute a portion of their personal history to an archive before utilizing editing software to create video vignettes.

Live program compilation reel, featuring teen participant FredriqueGuevara-Prip’s film Best Part, March 18, 2021

At the end of the series, Bradley attended a special premiere of the teen films, which the teens named as a highlight after having studied and been inspired by Bradley’s work.

Workshop coordinator Amara Thomas, Petrie Fellow for Teen and Community Partnerships at MoMA, recalled how “generous and encouraging Garrett was with the teens, giving everyone thoughtful comments and praise for their films,” which Amara went on to describe as, “an intimate portrait of their lives, family, and meaningful moments” during a time when teens have felt isolated from their communities and extracurricular hobbies due to precautions taken by schools responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Ginny Huo, senior coordinator for Teen Programs at The Studio Museum, shared how critical it was for youth to meet directly with the artist because “it helps expand their ideas on what’s possible for them.”

Access in Transition

One of the films featured in the final compilation was created collaboratively by the students at ReStart Academy, Euphrasian Residence, which is a Studio Museum in Harlem School and Community Partnership. ReStart Academy provides services for students in transitional settings throughout the five boroughs and upstate New York. Euphrasian Residence is a diagnosis center and rapid intervention center that serves teenage girls aged 12–17 who have been referred by the New York City Administration for Children’s Services. Teens spend an average of three months living communally with educators at ReStart before transitioning into foster care, adoption, or back to families and guardians.

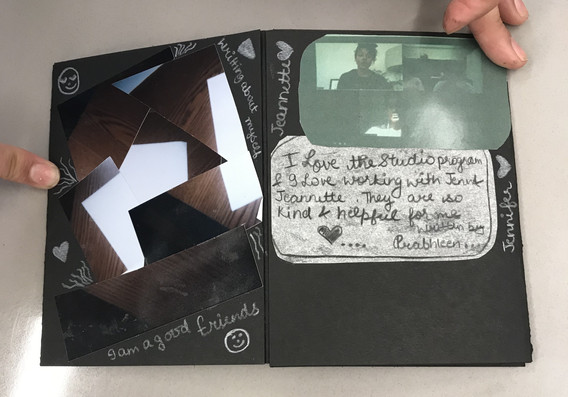

Artist educator Jeannette Rodríguez Píneda’s worked with students across 10 sessions focused on Garrett Bradley’s films, including America and the Academy Award–nominated TIME. Investigating how placemaking exists in the longer history of films by artists of African descent, students learned about personal archives, explored how writing and art making can serve as a tool for reclaiming symbols of power and powerlessness in their personal narratives, and considered how artists use memories to explore how cultural and individual identities are shaped.

Memories for the Future’s embrace of virtual programming due to the COVID-19 pandemic often meant turning to digitally accessible tools. The partnership with ReStart Academy was also virtual, but School and Community Partnerships coordinator Jennifer Harley and Rodríguez Píneda decided the transitional nature of ReStart Academy, and limitations around availability of digital filmmaking tools, necessitated a different kind of engagement. Working with teachers and counselors Iris Gruber, Ameria Alleyne, and Hema Senterhoovel, who lived and worked communally with students even through the pandemic, decided to pivot to analog. They collaborated to address additional concerns related to the youth’s privacy and safety, ultimately deciding to use disposable cameras. Students captured elements of their lives, each working together with Rodríguez Píneda to craft a digital film and using the prints to create a physical archive in book form that could be taken with them to their next location.

Photo documentation of final book projects from ReStart Academy students, featuring images they took to document their day-to-day lives, March 16, 2021

The necessity of these adjustments underscored the conditional accessibility of the digital sphere and the unreliable assumption that all people have a personal archive available. This, in part, contributes to further absences in archives of those who live, for periods or lifetimes, in transition. For students who can only keep a few belongings, and where phones and social media are not permitted, it was necessary to first create the material to pull from in order to contribute to a larger archival project. However, it also revealed the significance of working with physical materials when possible.

ReStart staff observed how this multifaceted approach spotlighted the students’ experiences and abilities, empowering them to interrogate narrative, value, and self-worth. Rodríguez Píneda described the students as “active figures of America in present form,” evoking the re-creation of what will always be lost or in the shadows of the archive. “Especially during this precarious moment where we do not have the privilege of in-person connection, the youths’ expression of love for themselves and each other is something I cannot get enough of,” says Rodríguez Píneda. The joy and affirmation illustrates how consistently accounting for access is integral to ensuring that the limitations of circumstances do not preclude the possibility of having the liberatory tools to chart past, present, and possible futures.

Photo documentation of final book projects from ReStart Academy Students, featuring images they took to document their day to day lives, March 16, 2021

Soundscape of community partner sessions with Garrett Bradley. March 16, 2021. Courtesy Jennifer Harley and Alex Parker

Facilitation and Democratic Engagement

Sarah Kennedy, assistant director of Learning Programs and Partnerships at MoMA, shared that a crucial component of Memories for the Future was “the dynamic roster of visual artists, composers, sound designers, and art educators” who facilitated the programs and created digital resources. Over the course of four public workshops that emphasized process over product, facilitators and contributors created space for democratic engagement that extended beyond the bounds of the free virtual workshops.

Composer and performance artist Jeremy Toussaint-Baptiste reminisced that what struck him most about Memories for the Future was the “generous spirit of open exchange and sharing from all sides: participants, facilitators, as well as lead artists. In the Scoring Workshop I co-facilitated with Udit, specifically, once we entered breakout rooms, he and I would check in on the smaller groups, only to find that the participants—who all ranged in specialization and level—were already teaching one another, sharing tips and knowledge in a way that feels increasingly rare.” Workshop participants were eager to connect with one another and had options for how to shape their own experiences, with the facilitators and with each other, across each iteration.

Printable and digital resources such as the DIY Guide and the Meditative Curriculum provided further opportunities for engagement with content outside the confines of the live Saturday workshops, empowering participants to work independently and engage in meaningful dialogue with those around them. Rodríguez Píneda, who authored the Meditative Curriculum, considers it “a continuation of the space shared during facilitation with a broader reach, providing access to the content that could spark internal dialogue with past versions of themselves, bringing them closer to themselves,” and to their own narratives and history.

The availability of digital resources also supplemented different learning styles. When thinking about having the widest possible swath of people engaged with the project of archival repair as possible, multiple, intentional, and fluid access points are essential. A crucial part of this was finding free, open-source, and otherwise accessible platforms to ensure there were no cost barriers around participation, whether someone was joining for a workshop or working independently.

The same spirit was emphasized in the live workshops. The facilitators prepared options for all levels of familiarity with technology and other participants got involved as well, suggesting workarounds and adaptations to what their peers had available.

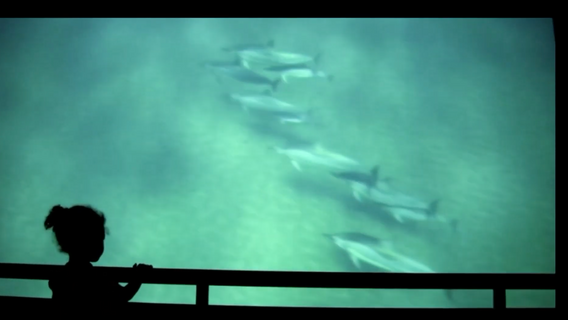

Still from Memories for the Future workshop participant Bonita Oliver’s Memory Is a Hungry Whale

Visual Storytelling Workshops recording, adapted to an at-home resource, January 23 and February 6, 2021. Edited by Jacarrea Garraway

Celebrating Collaboration and Community

In March’s final Memories for the Future conversation program, the participants’ final films were screened in compilations edited by filmmaker Jalea Jackson.

After the screening, we heard directly from the participant filmmakers. Though the films alone had already visibly moved panelists Bradley, Mathison, and Campt, the participants’ inspirations and processes for the films they created only made them resonate more deeply. Rodríguez Píneda, who saw the films after being involved in so many elements of the program series, remarked, “It was a special moment in which you understood just how precious time, life, our daily experience truly is.”

Visual and Sonic Quilt, featuring excerpts from submitted films from public, teen, and community partner workshop participants, March 18, 2021. Edited by Jalea Jackson.

Over 80 submitted films will live on in the archives of both The Museum of Modern Art and The Studio Museum in Harlem. When informed about the screening and archival submission, workshop attendee and artist Adam Bano declared that “as an underdog, as a Black and Brown Queer Trans Femme Muslim” this was, for them, “a dream come true.”

Bano and others across this project emphasized how art making and archives are not always accessible, especially for communities that bear the weight of historical and systematic exclusion, are disproportionately vulnerable to interpersonal and state-sanctioned harm, and are far more likely to experience transience than permanence. These violences of everyday life are mirrored in the archive, if not through the open documentation of this violence—in abundance or traces—then through its omissions.

If we want to continue moving toward a collective future of repair, we become responsible for documenting our changing lives, re-examining the balance of contributions with an eye toward absence and exclusion, and critiquing the archive. These acts of care bring us closer to one another and to the collective future we want to enact.

Memories for the Future taught us that this work becomes so much richer, and more enjoyable, when it is done together. Horizontal collaboration between staff at both museums, artist facilitators, and audience members rippled continually outward and began forming a new community, bonded by our investments in ourselves and in each other.

Studio Museum Education Department director Shanta Lawson commented, “One of my favorite moments during the culminating event was viewing the Zoom room and the chat in the moments after the screenings. It was clear that a lot of us were choked up, tearing up, or just gushing after viewing such poignant, personal, creative contributions. In that moment, and within the discussion afterward, I felt an undeniably strong sense of community—with the artists, facilitators, museum staff, and participants—through the collective experience of responding to a shared invitation.”

The participants in Memories for the Future have joined a long tradition of complicating what an archive is thought to be, while exposing its relatively simple core: a collection of things that people thought were important. By engaging in the act of creation and sharing their work back out, participants in Memories for the Future challenged dominant ideas of what might belong in archives, saying, “This—what we have experienced—is important, too.” And in doing so, they have begun to shape what is possible for our collective future.

Still from Memories for the Future workshop participant Raja Khuri’s moon blue (ii)

Recording of Memories for the Future’s final program, Garrett Bradley, Trevor Mathison, and Tina Campt in Conversation, moderated by Ravon Ruffin and Isa Saldaña, March 18, 2021. Courtesy The Museum of Modern Art

Related articles

-

Memories for the Future

Garrett Bradley’s America inspires and challenges us to play an active role in making and telling our stories.

Ravon Ruffin

Jan 20, 2021

-

Re-Imaging America

Artist and filmmaker Garrett Bradley speaks about her re-envisioning of Black history.

Thelma Golden, Legacy Russell, Garrett Bradley

Nov 19, 2020