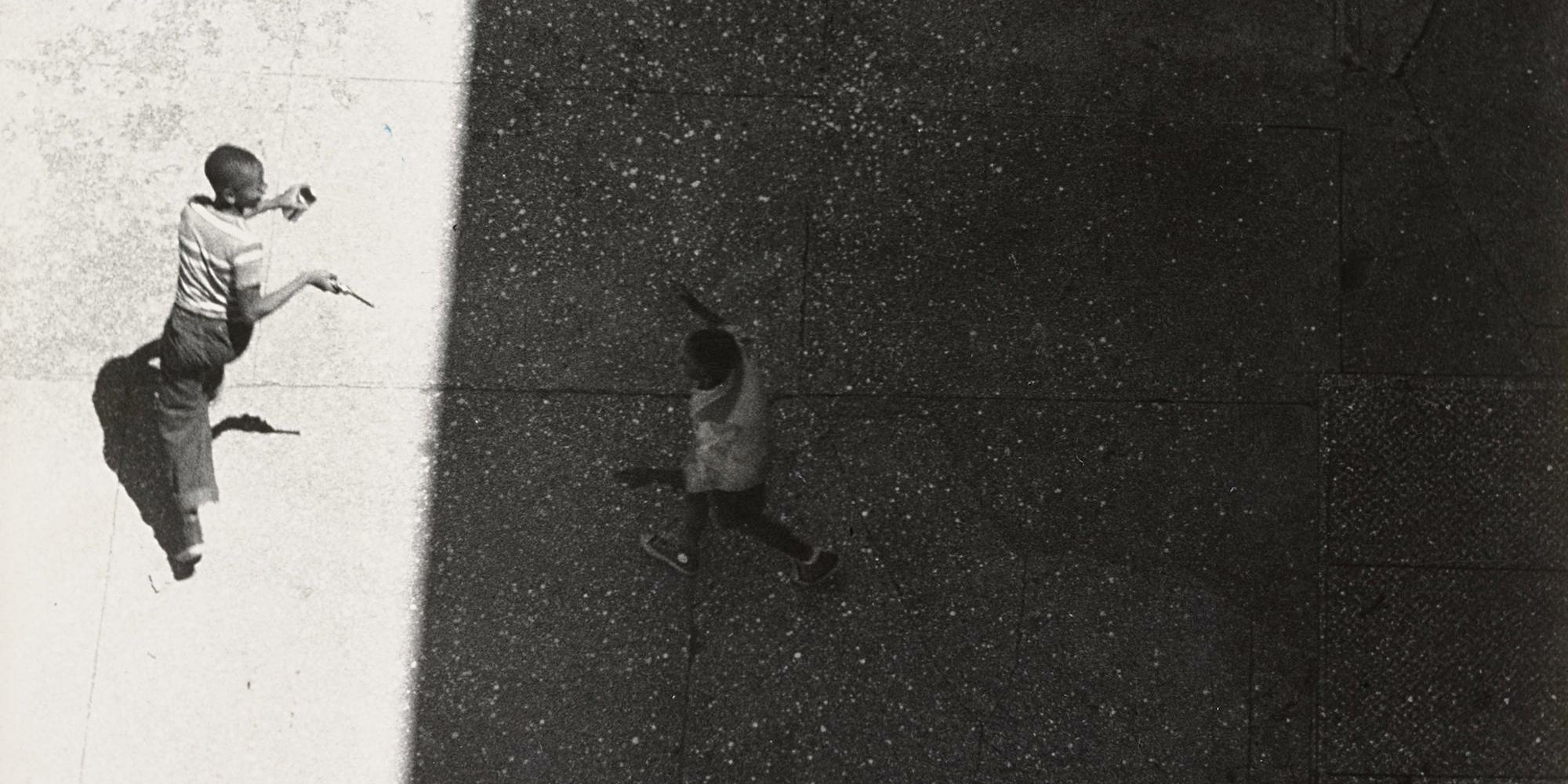

Roy DeCarava’s Play of Sun and Shade

Poet Fred Moten finds that, in its absence, color is everywhere in a Roy DeCarava photograph from 1952.

Fred Moten

Mar 11, 2021

The text below is excerpted from the MoMA publication Among Others: Blackness at MoMA, edited by Darby English and Charlotte Barat. Chosen by the New York Times as one of the Best Art Books of 2019 and by ARTNews as one of the Best Art Books of the Decade, Among Others is the first substantial exploration of a major museum’s uneven historical relationship with Black artists, Black audiences, and the broader subject of racial Blackness. For the next few months, we will be featuring selected excerpts on Magazine.

Blackness is the ceaselessly miraculous demonstration that there is no black and white, just sun and shade. All throughout his long and glorious career, Roy DeCarava serialized this insight as an irreducible element of art consciousness’s remedial education, as he registered the condition that is without remedy. He photographed people continually getting over the fact that they can’t get over, revealing their terribly beautiful inability to get over the fact that they do, which is given in looking back in mournful wonder, ahead in worn anticipation. Insofar as the photograph in general looks back and forth like that, its existential condition is given when it regards blackness in play, as the play of sun and shade.

The capaciousness of black’s color field is actualized out from the outside, all in all, all this insight forming outside inside out. Efforts to achieve black’s purity misunderstand its depth of study. In the documentation of play’s concrete abstraction, where abstraction folds in documentation, given understandings of abstraction therein being unfolded, unraveled, taken away, black is an all-but-gray-blue university—the contemplative eclipse of portraiture and its substructural meta/physics. It’s like a detail in a Bruegel that Bruegel left out; or something left out in a Bruegel and recovered from and in its immersion in a terrible, projective, illuminating solution of silver and gelatin. Particulate dispersion is applied in the interest of showing, of demonstration, of monstrosity. Faces are held between torn up and hiding, grotesquerie and umbrage. That’s our nonparticulate dispersion. The development of excluded essence is a tragedy that DeCarava renders miraculous. What it is to look at black as black, all up in all of it so emphatically that in its absence color is everywhere, is where DeCarava carefully, playfully, unsettlingly resides.

What is it to reside without settling? Is that is or is that ain’t like being stuck in sweetness, held in life? Black life is like Iife in hell, or on the el, which is the sound of joy, Sun says. Sun who? Son House, I think, unhoused some day in Harlem’s bright Mississippi, two little boys drawing out that string in strange, marooned dispersion. See, their play is fraught. Insistent movement. Mobility that stays, that’s all but still but for the shift in (over)tone. Captured motion’s constant flight turns out always to sound like something. The shit is eerie enough for the difference between loud and quiet not to signify. Silence and blackness are more + less than one in this regard, which is a kind of regardlessness, as the train falls through the trees, skyscrapers, and everything, and nothing. The sound DeCarava sees is movement, a resonance of back and forth in falling from partition to partiality, a preference for our social incompleteness, individuation played out, relation exhausted in obscure, tensile revelation held right here: what’s happening? I know something’s happening ’cause everything is moving. Now it’s gone. Every photograph is a photograph of that, which an actual photograph of that makes deafeningly clear. It’s not that it’s not a sin and a shame that Sun and Shade is so beautiful. It’s just that black, in being so beautiful, is forgivenness.

Roy DeCarava. Sun and Shade. 1952