Reimagining Blackness and Architecture

What is architecture? Ten architects featured in a new MoMA exhibition and online course weigh in.

Arlette Hernandez

Feb 25, 2021

I knew I wanted to be an architect before I even had the language to express what architecture was. As a child, I would look at the buildings around me and wonder who made them. In my mind, I imagined it was someone like my grandmother, who would dream up designs for beautiful necklaces; or someone like my mother, who would take broken pieces of furniture and find ways to make them whole and new. It wasn’t until I was older that I realized that the buildings around me were not made by people like my mother and my grandmother. Those buildings weren’t made by anyone who looked like us.

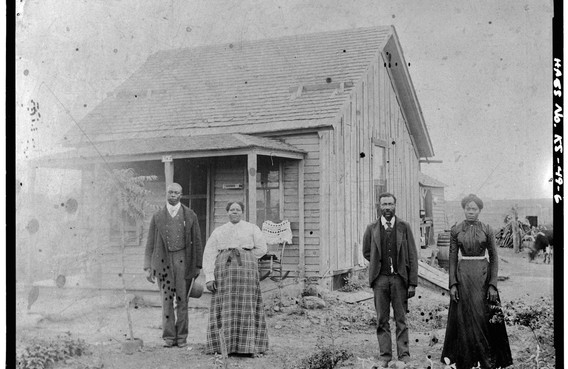

For Black people in America and across the world, architecture was not made to support us. In many instances, architecture was designed to harm us. Through white supremacy, forced labor, imprisonment, and countless discriminatory laws, anti-Black racism was literally designed into the built environment. And these practices determine not only where we can live, but how we can live.

Photo of the author and her mother outside their former home in Miami, Florida. Their neighborhood would flood regularly after storms and heavy rains. c. 2001

These ideas are a point of departure for the exhibition opening this week at MoMA, Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America, as well as a new online course, Reimagining Blackness and Architecture. Through original films, audio interviews, and short readings, the course will introduce learners to the ways in which Black artists, architects, scholars, and writers have responded to these histories of violence and exclusion to create new ways of being, reimagining the spaces that have refused us. My hope is that, through this course, we can begin to not only have meaningful conversations about building more equitable spaces, but also inspire new generations of emerging creatives who, like myself, never saw themselves reflected in architecture. We encourage everyone, regardless of your profession or where you’re located, to engage in these conversations by enrolling in the course at any time.

We asked the participants in Reconstructions, who collectively form the Black Reconstruction Collective, to respond to two questions: What is architecture? And what does it mean to be an architect? Their answers reflect some of the important themes explored in both the exhibition and the course, encouraging us to think more deeply about our understanding of not only what architecture is, but what it can be.

–Arlette Hernandez, Volkswagen Fellow for Digital Learning

Germane Barnes, working on A Spectrum of Blackness in Miami, Florida

Architecture to me is about space. Not specifically the construction of space, which is how it’s typically defined. For me, it’s about the occupation of space. It’s about the performative aspects. How are we supposed to interact within space? If you’re a member of a marginalized community, how do you maneuver in space? For example, if I’m on an elevator with someone who doesn’t know me, I might need to actually push my floor first so that this individual feels safer and understands that I’m not trying to follow them to their floor. That’s why I think it’s important to ask people, “Do you think you experienced space intentionally, or clumsily?”

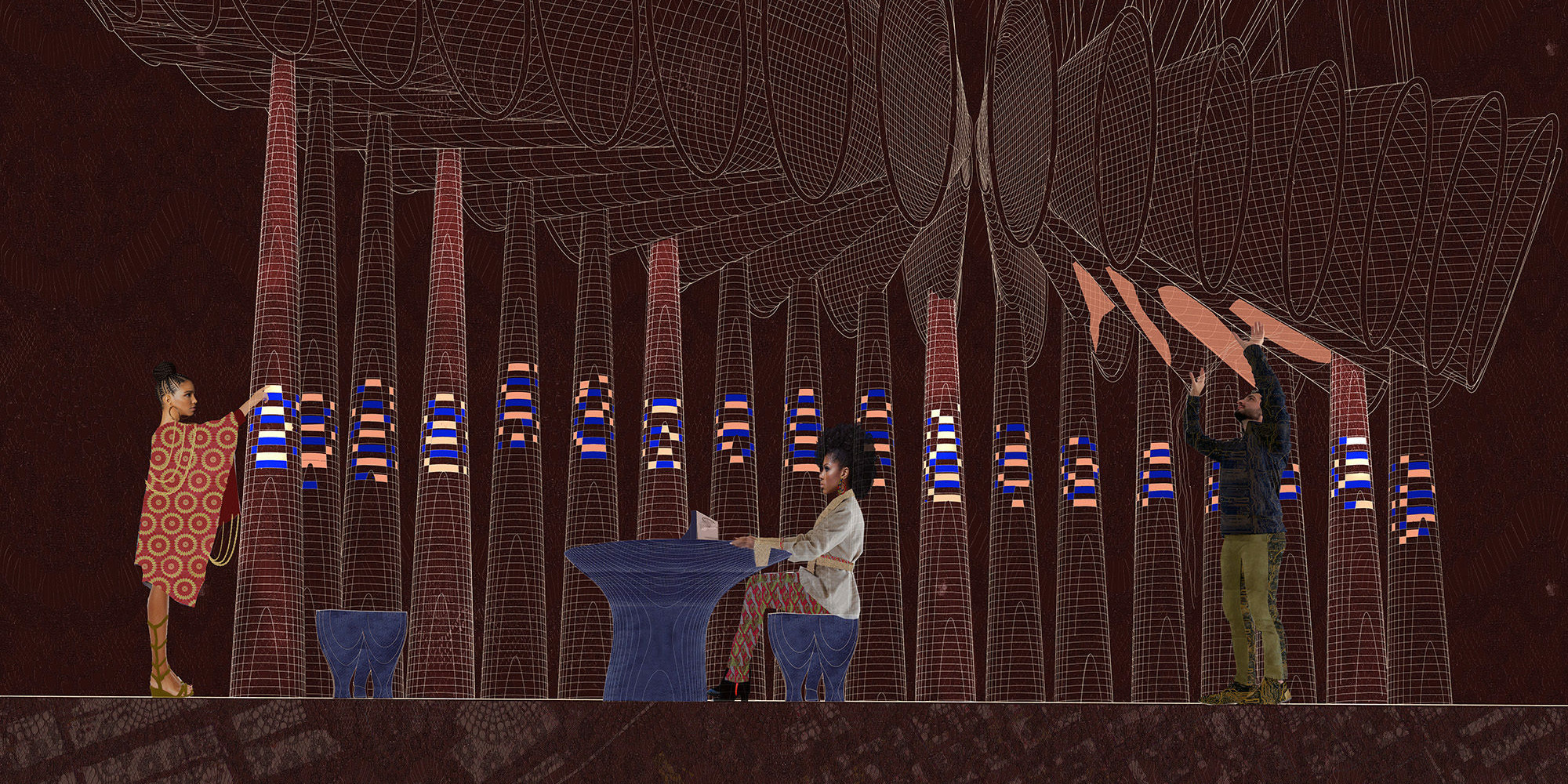

Olalekan Jeyifous, working on The Frozen Neighborhoods in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, New York

For me, working with the medium of architecture is just a way of defining space, or creating space, or generating space, or marking space; it’s a way of acknowledging the way people navigate and move through space and the ways they congregate. In a sense, I think I’m providing an alternative to the kinds of forces and systems that architecture as a practice has served in America for a very long time, which are unjust. I’m thinking about how architecture serves community and serves humanity.

Walter J. Hood, working on Black Towers / Black Power in Oakland, California

Architecture, to me, means power. Even today, as I look out into the skyline, the buildings that I see are about power. They’re less about community. And so for me, how do I take that object of power and bring it into a space where those who haven’t had that power can transform it and use it for themselves? In doing that, architecture becomes something that maybe the community can begin to use as a way to be part of the conversation.

Olalekan Jeyifous. Plant Seeds Grow Blessings. 2020

At this moment in time, all of us should be thinking of radically different worlds.

Emanuel Admassu

Emanuel Admassu, working on Immeasurability in Atlanta, Georgia

For me, architecture is not only about making buildings. It is a world-making practice. So, instead of just thinking, “We’re going to design a new building,” I want to ask, “How can we design a new environment that allows for other perspectives, for other forms of communality and relationships with one another?” The only way architecture can survive is if it decouples itself from this idea that we have to constantly produce property. When we do that, we can go back to certain spaces and look at them differently. Architecture gives us the tools to imagine radically different worlds. And I think at this moment in time, all of us should be thinking of radically different worlds.

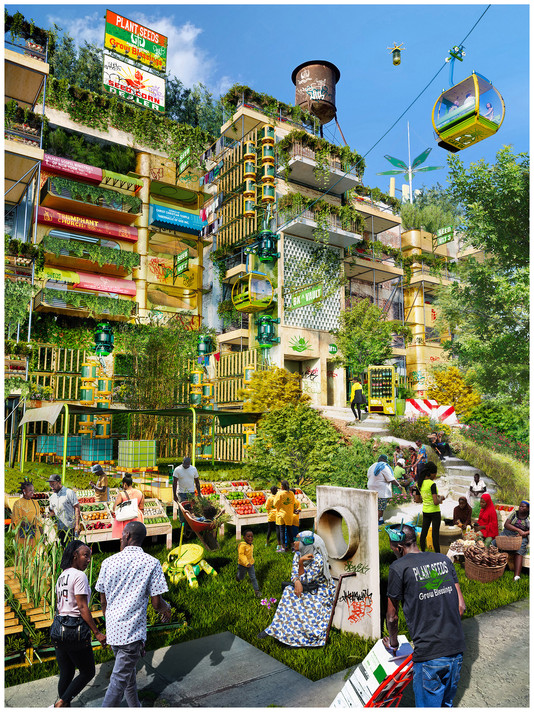

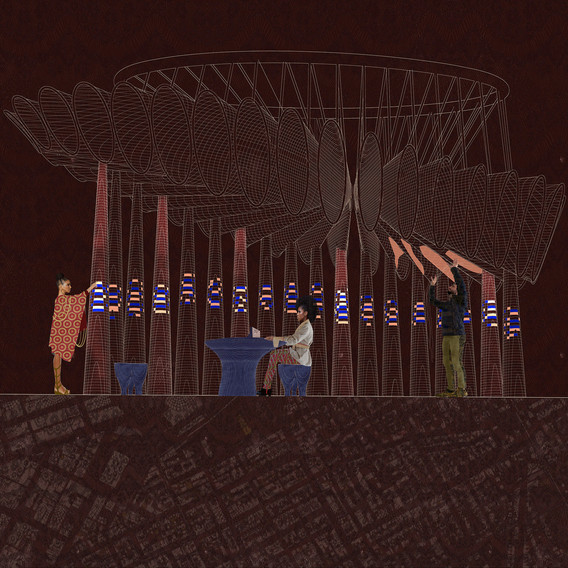

Sekou Cooke. We Outchea. 2020

Sekou Cooke, working on We Outchea in Syracuse, New York

Some people might imagine that architects are only concerned with designing and creating buildings. But there are many, many more layers—of society, economies, politics, of the ways we live in the physical environment. Architecture is concerned with the psychology of what it means to be in space. As architects, we’re concerned with how we interact with each other as human beings.

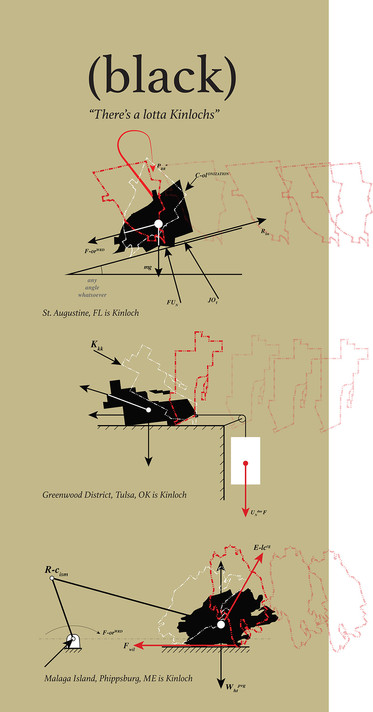

Amanda Williams, working on “We’re Not Down There, We’re Over Here” in Kinloch, Missouri

I’m often described as both an artist and an architect. But I think a long time ago, I decided that architecture, in the way that it’s practiced today in the United States, couldn't really hold the bigness or expectations that I had for what architecture should be doing. And so object-making, artistic explorations, questions, and installations that use architecture as a medium, or that use architectural space as the canvas—all of these things are really important to me. Through my work, I get to navigate spaces that allow me to bring in whatever I need in order to have conversations about whatever is really important to me. So for me, that’s really what architecture means.

J. Yolande Daniels, working on Black City: The Los Angeles Edition in Los Angeles, California

I think that architecture is a kind of process and social practice. It is the building of form, but for me, as I’m building forms, I’m also analyzing and trying to understand how they came to be. So my role as an architect is not just to build but it's also to take apart, because my role is to understand how the built fabric came to be.

Amanda Williams. Spatial Diagrams 4. 2020

Felecia Davis, working on Fabricating Networks in the Hill District, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

As a Black architect, I’ve looked at architecture as something that is expansive. It involves organizing people, organizing a kind of social network to begin to have a conversation about what building could mean. That is just as much a part of making architecture as making a building with bricks and mortar. I think it’s important to make space for yourself to dream and not to listen to the negativities of people who say that your ideas are not real, and that it’s never going to be built. I would say they’ve got it wrong. That, in fact, a dream is a built thing. It is a real thing. And it’s important to be able to do that to actualize yourself in the world.

Mario Gooden, working on The Refusal of Space in Nashville, Tennessee

Architecture is much more than the aesthetic practice of making buildings or giving form to an idea. Architecture is about making space. Architecture is about situating relationships within space. The Black Reconstruction Collective was formed as a means of visibility and as a means to give support to other Black creatives: designers, architects, artists. In order to be an architect, one has to be able to see oneself within that role and be able to see others in that role. And so the Black Reconstruction Collective also sees itself as a form of mentorship to others and to younger people like myself when I was a middle schooler, wondering how I might become an architect despite never having seen an African American architect.

V. Mitch McEwen, working on R:R in New Orleans, Louisiana

The architecture field in the United States is so predominantly white. Out of the 100,000-plus licensed architects in this country, only two percent are Black. So there’s literally just a couple hundred Black women who are licensed architects in this country. What that means is that we have to unlearn a false history and at the same time cobble together the actual history. We’re still learning about Black practitioners who did amazing work between graphic design and architecture. And part of what we’re doing at the Black Reconstruction Collective is unearthing these stories, because the erasure of Black and brown people, of Indigenous people, from architecture and design—it has nothing to do with us. It’s not because we weren’t there.

Felecia Davis. Drawing 2. 2020

The exhibition is made possible by Allianz, MoMA’s partner for design and innovation.

Volkswagen of America is proud to be MoMA’s lead partner of education.

MoMA Audio is supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies.