Hounding the Mad Beast of Function

A book excerpt, audio, and a podcast delve into Meret Oppenheim’s fur-covered cup.

Nov 18, 2020

Below, in an exclusive excerpt from MoMA’s One-on-One series, and presented as part of Virtual Views: Surrealist Women, Carolyn Lanchner tells the origin story of Meret Oppenheim’s notorious Object. (Get the whole book today.) You can also read and listen to Brenda Shaughnessy’s poem “The Impossible Lesbian Love Object,” which gives voice to the sculpture, and hear Abbi Jacobson ruminate on this “weirdly risqué” artwork, made when Oppenheim was 22, in the podcast A Piece of Work.

Carolyn Lanchner on Meret Oppenheim’s Object

Meret Oppenheim’s 1936 Object, her Fur-Covered Cup, Plate, and Spoon[1], caused such a sensation in The Museum of Modern Art’s Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism, an exhibition in the same year it was made, that many visitors “seemed to take it as a symbol of the Exhibition and of the Museum itself.”[2] In April 1937, two months after the exhibition had finished its New York run and was touring other museums in the country, Alfred H. Barr Jr., The Museum of Modern Art’s director and the organizer of the exhibition, provided his own assessment of the object’s impact: “Few works of art in recent years have so captured the popular imagination . . . the ‘fur-lined tea set’ makes concretely real the most extreme, the most bizarre improbability. The tension and excitement caused by this object in the minds of tens of thousands of Americans have been expressed in rage, laughter, disgust or delight.”[3] A comment earlier that year in a column reprinted in several small-town newspapers corroborates Barr’s observations: “‘What Next?’ cries the surrealism-beset world. Just as though things weren’t dada enough, the surrealists had to come to America with their fantastic art. The fur lined cup and saucer with spoon thrown in for good measure gives an idea of all the goofiness started by the surrealist art exhibit in New York.”[4]

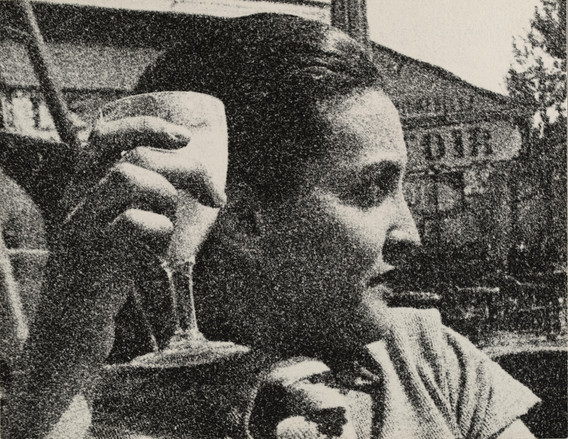

Man Ray. Meret Oppenheim. 1932

The tension and excitement caused by this object in the minds of tens of thousands of Americans have been expressed in rage, laughter, disgust or delight.

Alfred H. Barr Jr.

Barely a year before Oppenheim’s furred exemplar of contagious goofiness began agitating American audiences, its substance was no more than the ephemeral banter of table talk at Paris’s Café de Flore. The participants were Oppenheim and two friends she had unexpectedly encountered, Pablo Picasso and Dora Maar. Oppenheim happened to be wearing one of the fur-covered bracelets she had been making for the designer Schiaparelli. Her companions admired it, and one thing led to another: as they talked and joked about the bracelet, Picasso suggested that anything could be covered with fur. According to Oppenheim, she replied, “Even this cup and saucer?”[5] Very soon thereafter, when André Breton, Surrealism’s chief theoretician, asked her to contribute to the Exposition surréaliste d’objets, an exhibition of Surrealist objects being planned at the Galerie Charles Ratton, she recalled the speculations floated at the Flore and forthwith bought a large cup, saucer, and spoon at a cut-rate department store and covered its glazed white surfaces with the pelt of a Chinese gazelle already in her possession.[6]

Oppenheim’s no-nonsense execution contrasts sharply with more typical Surrealist maneuvering, yet the cup itself embodies fundamentals of the movement’s goals. Its genesis “corresponds with rare precision” to the Surrealist will to produce art through the collectivization of ideas abetted by chance.[7] Breton himself, in his article “Crise de l’objet,” published shortly after the close of the Ratton exhibition, recognized the fur cup as a realization of his demand that the Surrealist object must “traquer la bête folle de l’usage” (hound the mad beast of function).[8]

Notes

1. Object was the title, “fur-covered cup, plate and spoon” the medium, given in the catalogue of the Museum’s 1936 exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism. Meret Oppenheim’s own title was Assiette, tasse et cuillère couvertes de fourrure, the simple medium description that the Museum translated. After 1938, the title Le Déjeuner en fourrure was frequently used, although not by The Museum of Modern Art until 1963.

2. Marcel Jean, The History of Surrealist Painting, trans. Simon Watson Taylor (New York: Grove Press, 1960), p. 274. Originally published as L’Histoire de la peinture surréaliste (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1959).

3. Alfred H. Barr Jr., “Surrealism: What It Is in Literature and the Arts—Its Origin and Future,” World Today: Encyclopedia Britannica 4, no. 4 (April 1937), p. 4.

4. Bloomington Pantagraph, February 9, 1937, repr. in Bice Curiger, Meret Oppenheim: Defiance in the Face of Freedom (New York: Parkett Publishers, 1989), p. 39.

5. Ibid. Virtually every monograph on Oppenheim contains a version of this incident.

6. The Museum’s Department of Conservation has examined the fur and concluded that it is not Chinese gazelle. Exactly what it is has not been determined.

7. Josef Helfenstein, “Against the Intolerability of Fame: Meret Oppenheim and Surrealism,” in Jacqueline Burckhardt and Curiger, eds., Meret Oppenheim: Beyond the Teacup, exh. cat. (New York: Independent Curators, 1996), p. 30. The exhibition for which this was the catalogue appeared at the Guggenheim Museum, New York (June 28 to October 9, 1996), and traveled.

8. André Breton, quoted in ibid., p. 29.

Related articles

-

New to MoMA

Leonora Carrington and the Visual Language of Mexican Surrealism

Two new acquisitions display the artist’s interest in the occult.

Cara Manes, Anne Umland

Feb 19, 2020

-

Poetry Project

The Impossible Lesbian Love Object(s)

Brenda Shaughnessy gives voice to Meret Oppenheim’s Object.

Brenda Shaughnessy

Nov 5, 2019