Remembering Zarina, 1937–2020

MoMA’s staff recalls the widely admired artist.

Portrait of Zarina by Ram Rahman

I first learned about Zarina Hashmi as a graduate student working on early Mughal architecture in India in the 1980s. I had traveled to Aligarh, where Zarina was born in 1937 and home to one of India’s great universities, where her father taught, to meet with a number of scholars. One of them, who was an old family friend of the Hashmis, asked me if I knew of Zarina. I did not. Fast forward almost 30 years to a chance encounter with her in New York City, and the rekindling of an old memory. I think she was surprised, maybe even a little amused, that I had not only been to Aligarh but that she was still talked about there, as her family had fled to Pakistan after Partition. Over many studio visits and shared moments, I came to admire her quiet intelligence and elegant manner, and to cherish her stories about the worlds she knew and the worlds she imagined. We talked about Aligarh and Delhi, London and New York, nomadic existences, and the need for someplace to call home.

Zarina did not have to say much, or speak forcefully. Her art did that and more for her, with its complex associations between traditional Indian art and craft, and the languages of modernism filtered through her deeply cultured mind. Blinding Light, for instance, with its squares of gold leaf over paper, is both a meditation on craft and a sublimely abstract work that conjures associations with Agnes Martin as much as it does with Indian temple painting. And Santa

At her best, Zarina made the invisible filaments of memory tangible and alive, evoking distant spaces and current feelings; a life left behind and a life well lived. Her work could be stunningly beautiful and haptic as easily as it could be cerebral and abstract—but it was always meaningful and carefully considered, as she was herself. Just before the novel coronavirus shut down travel, I was in India on the tail end of a trip to Asia, and the last exhibition I saw there was a beautiful survey of Zarina’s work at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art—a perfect coda to my first hearing about her, and a memory I will never forget, just as I will never forget her.

–Glenn D. Lowry, David Rockefeller Director of MoMA

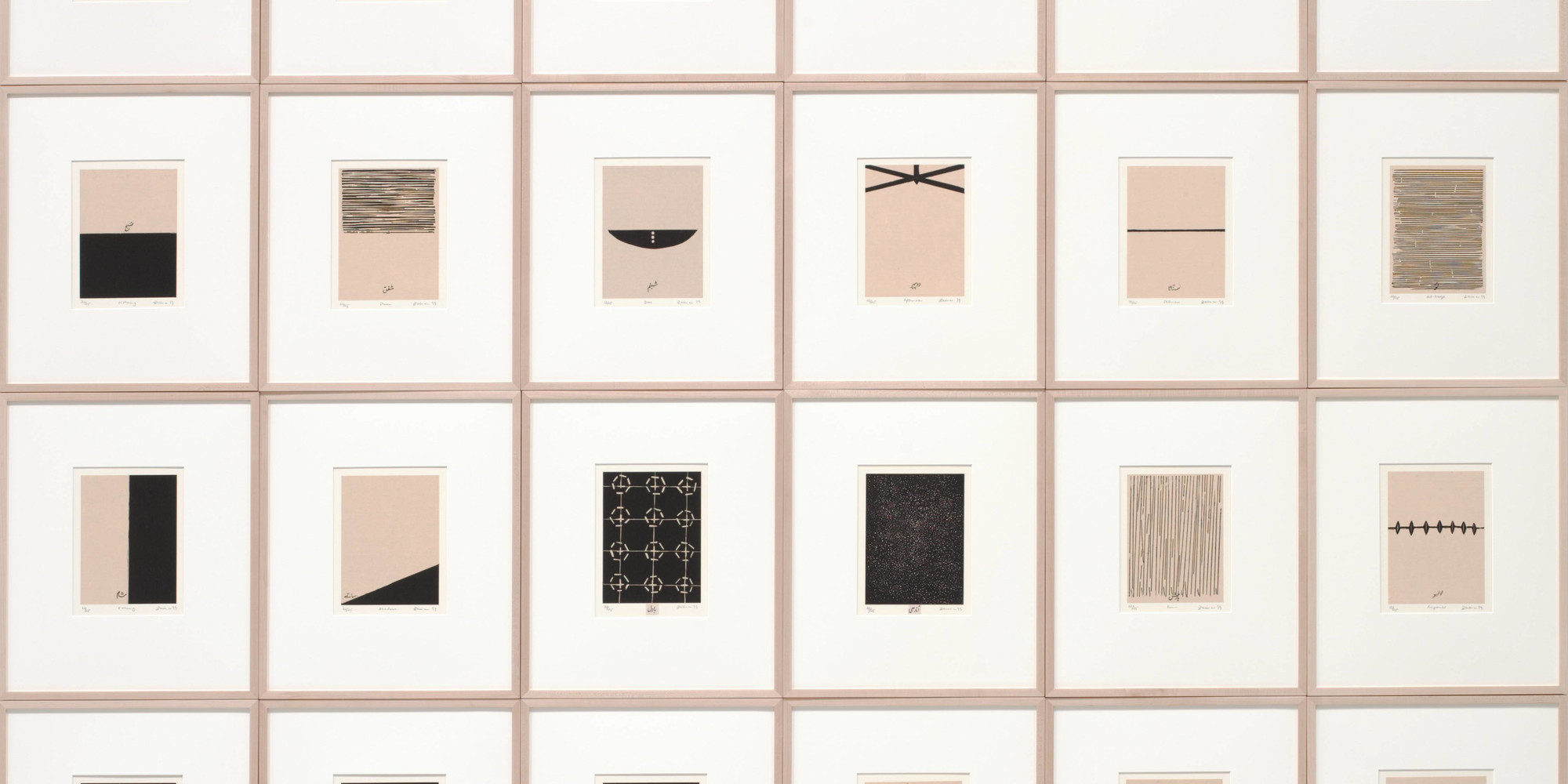

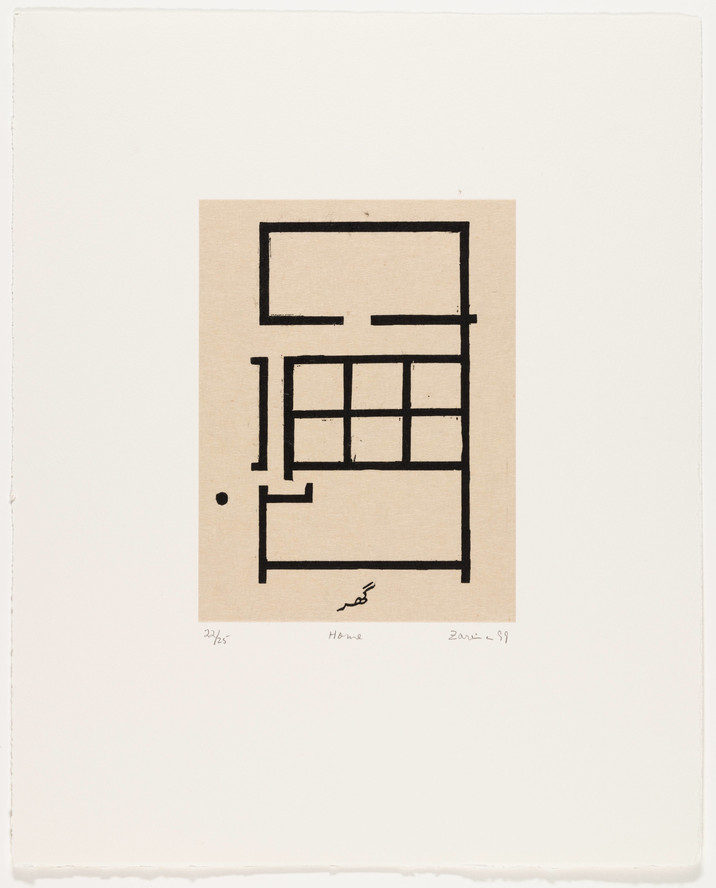

Zarina. Moon from Home Is a Foreign Place. 1999

As I was touring the Chelsea galleries in the summer of 2009, Zarina Hashmi’s Home Is a Foreign Place, a portfolio of 36 woodcuts published a decade earlier, stopped me in my tracks. I had just opened a group show at MoMA titled In & Out of Amsterdam: Travels in Conceptual Art, which focused on the role of travel, both literally and figuratively, in the art of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Zarina’s work provided a formidable echo to all of the ideas that I had tried to explore in my show. Home Is a Foreign Place was not about a distinct network of relationships during a brief period of time, but the perpetual wanderings of an artist around the world. For Zarina, home was not defined as the faraway place of her childhood but wherever she had decided to settle. Home was a present-tense verb.

Zarina happened to be at the gallery when I stopped by. A few weeks later, on a hot day in August, I paid a visit to her home and studio on West 29th Street. I remember it as a small loft in which everything seemed to fit perfectly—a home carefully built to reflect its occupant rather than the industrial building or even the city around it. Surrounded by objects from across the globe, we sat down and started talking. A discussion about her past was like embarking on a whirlwind journey as she spoke of all of the cities that she had once called home. While we sipped tea, our minds traveled from New Delhi to Bangkok, from Paris to Bonn, from Los Angeles to Santa Cruz, until I completely lost track of time and place.

Zarina loved words. As she told me on that day: language always came to her first, images only followed. Her mother tongue was Urdu and many of her prints illustrated words that she felt were on the verge of disappearing. I remember wondering that afternoon whether she felt a warm breeze, an exquisite fragrance, a flash of light, or whether any passing moment might cease to exist if left unnamed. As she described one beautiful word after another, it became clear to me that Zarina’s art was about suspending time. And, as I said goodbye, I remember the slight sadness in her eyes when she told me how much she had enjoyed gliding in her youth. She just couldn’t bear the thought of having to come down again. Her art, at least, will stay up there forever.

–Christophe Cherix, Robert Lehman Foundation Chief Curator of Drawings and Prints

Zarina. Beyond the Stars. 2014

Forty-four years separate MoMA’s first acquisition of Zarina’s work, in 1974, and its most recent, a span that serves as a testament to the enduring career and lasting influence of this extraordinary artist, who passed away earlier this week. I came to know Zarina through our shared passion for printmaking. Hers was sparked by the innate potential in handmade Rajasthani paper, and fanned by stints at Atelier 17, Stanley William Hayter’s esteemed laboratory for intaglio mediums in Paris, and at Toshio Yoshida’s woodblock studio in Tokyo. It always seemed to me that she had been everywhere and knew everyone. Displaced by Partition, hers was a peripatetic life, as she sought an ever-elusive sense of home wherever she traveled; she found community all along the way, from Aligarh to Bangkok to London. It was impossible not to be drawn to her: she was fiercely intelligent, wildly independent, breathtakingly elegant, wickedly witty, effortlessly poetic, all terms that equally describe her body of work. Acquired in 2018, Beyond the Stars seems like a fitting memorial: a monochrome woodcut flecked with gold leaf, a shimmering depiction of the heavens and the celestial universe of which she is now part.

–Sarah Suzuki, Curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints

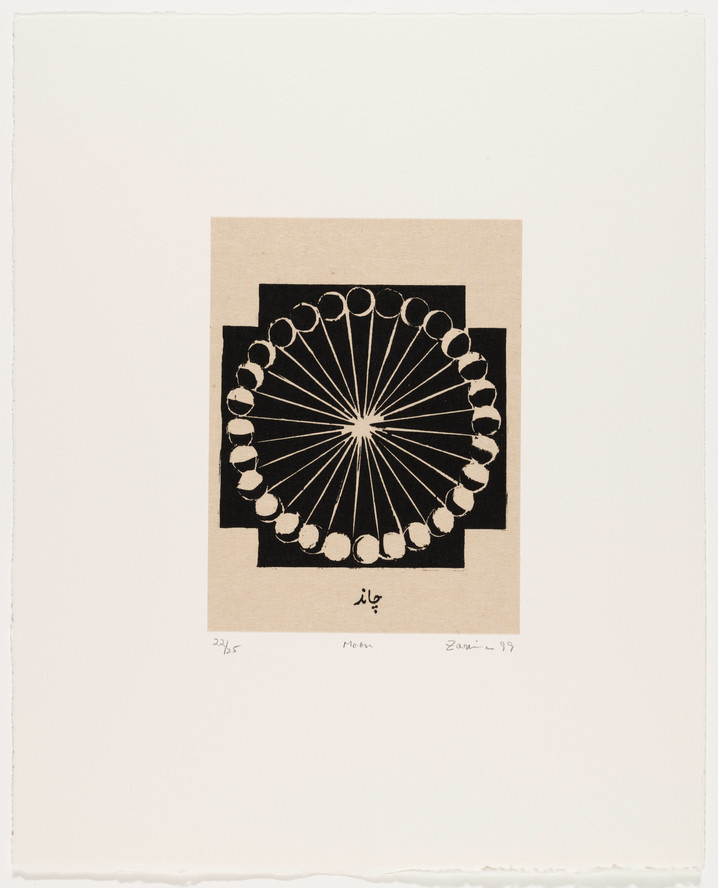

Zarina. Home from Home Is a Foreign Place. 1999

From the 13th century on, throughout Persian and Urdu poetry, art, architecture, and music, the door, the gate, and the threshold are used as leitmotifs to symbolize the ritual aspects of one’s movement between and into new worlds. The great Persian poet Hafiz, for example, often used the terms dar, astan, and chaukhat (a room, a space, and threshold, and similar in meaning) to suggest that one’s desire or veneration was subject to a mythic architecture through which one must pass. More frequently, the architecture of shrines (dargahs) and other sacred spaces was intended to be a metaphorical expression of doctrine inscribed on the walls as poetry. Language, it seemed, was to be occupied and built as much as it was to be revered.

For Zarina Hashmi, these same constructions—of language and desire, of space and longing, of the physical world meeting the ephemeral—all constituted realms throughout her life and work in which she recognized unerring transits of meaning. Born in India 10 years prior to the violent 1947 Partition with Pakistan, she was forever subject to its afterlives as her parents and siblings moved to Karachi. Such departures reconfigured the ways in which Zarina was at once guided by constellations across well-trodden pathways, but more often into invisible landscapes that she was forever bound. Loss cannot be circumscribed. Among Zarina’s prints, the fractures of geography—itself an invention of lines, fields, and planes—mark edges and horizons which both drew and repelled her. The boundaries that define territory also mark each one of us: our origins, our hopeful movements toward a home that we may yet find. We are fortunate to stand at the thresholds of an architecture Zarina has assembled with words and images, peering inward to an incalculable and immense universe.

–Sean Anderson, Associate Curator in the Department of Architecture and Design

Portrait of Zarina by Dev Benegal

ka.ī baar is kā dāman bhar diyā husn-e-do-ālam se

magar dil hai ki is kī ḳhāna-vīrānī nahīñ jaatī

How often it is filled with the beauty of both worlds,

and yet the emptiness of my heart remains

–Faiz Ahmed Faiz

(quoted by Zarina and translated by Sadia Shirazi)

Well before I met Zarina in New York, her story had permeated my consciousness, exemplifying two defining characteristics of the 20th-century artistic experience: abstraction and exile. Through her work she invites us into her homes and worlds, with their alluring geometries and cosmopolitan geographies, while keeping us at bay by gently underscoring linguistic barriers and the limits of image making. Her rigorously rendered lines evince the significance of language and space that are central to her conception of home, an idea that firmly adhered to her and her practice. That idea’s inherently constructed nature and enduring fragility were lifelong subjects of inquiry for Zarina, guided by poetry, literature, conversations, and correspondence in her beloved Urdu.

For an artist who made her life the subject of her practice, biography acts as both an enabler and a crutch. The abundance of significant details about Zarina’s familial relationships, her peripatetic life, her living spaces, her teachers and friends—enriching and evocative as they are—have often overshadowed engagement with her sophisticated work with paper, wood block, and ink.

Unlike some of her peers and close friends, Zarina received widespread recognition during her lifetime, and her work will undoubtedly continue to be studied, taught, collected, and exhibited around the world. As home follows her into higher realms, she leaves behind memories of her inimitably sharp wit, her impeccably elegant style, and the gifts and challenges of a distinctive practice and diasporic subjecthood.

–Rattanamol Singh Johal, Mellon-Marron Museum Research Consortium Fellow in the Department of Painting and Sculpture

You can read an interview with Zarina, and hear her speak about Home Is a Foreign Place.

Related articles

-

Tribute

Remembering Abstract Pioneer Jack Youngerman, 1926–2020

From Paris to New York, Youngerman's long dedication to abstraction celebrated shape and color.

Prudence Peiffer

Feb 24, 2020

-

Tribute

Three Artists on the Gifts of John Baldessari, 1931–2020

An homage in three acts: Louise Lawler shares a postcard, Christopher Williams remembers Baldessari’s studio, and Stephen Prina sings one of the great Conceptualist’s paintings.

Louise Lawler, Christopher Williams, Stephen Prina

Jan 15, 2020