Raymond Pettibon Breaks His Own Records

It’s easy to love the iconoclastic artist’s era-defining album art...even if he doesn’t.

Jason Persse

Feb 5, 2020

The important thing to remember here is that the drawings came first. The rest is timing, serendipity, and a healthy dose of nepotism. That’s how you explain the fact that Raymond Pettibon isn’t crazy about punk despite that fact that, for better or worse, he helped invent it.

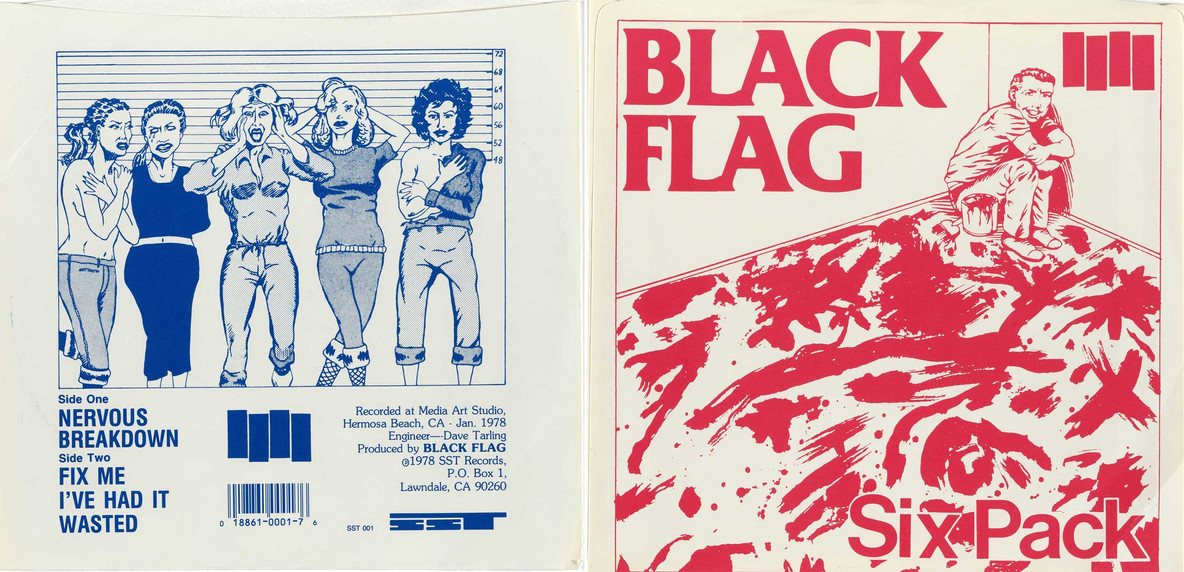

Around 1976, Raymond Ginn (“Pettibon” is a nickname that stuck) was already drawing—a lot—when his younger brother, Greg, was getting a band together. In short order, Raymond had supplied the band with a name—Black Flag—and what is surely the most iconic logo in punk rock: the infamous “four bars” design that captivated and terrified a generation of Southern Californians. (In the Black Flag episode of the Art of Punk video series, a typically wry Pettibon deadpans, “It’s probably one of the more popular tattoos besides...swastikas, or whatever.”) He also began supplying Black Flag with his drawings, of which he was making hundreds, for use first on flyers and, later, on 7" singles. This seemingly frenzied level of production has remained a constant throughout his career. As former MoMA curator Robert Storr puts it in Spencer Leigh’s documentary Raymond Pettibon: A Collection of Lines, “The whole of Raymond’s work is racing thoughts.”

Raymond Pettibon’s drawings on Black Flag 7" singles: from left, the back cover of “Nervous Breakdown” (1978) and the cover of “Six Pack” (1981)

But the drawings always came first, before someone else slapped a band name or a logo on top and headed to the nearest photocopier (or, in those early days, mimeograph). Even as the band moved to making full-length LPs, Pettibon wasn’t creating art to order. “They’d go through two hundred drawings and take the worst one possible. The one I did as a joke or something,” he says in the book Homo Americanus. “But then, you know, punk rock is music, it’s not art.”

To hear others tell it, though, Pettibon was more than just a good sport with an open portfolio. Many recall him providing only a few choices for each flyer or cover, depicting the most provocative possible imagery, a steady stream of drug-addled hippies, violence, mushroom clouds, wanton sexuality, juvenile delinquency, erect penises, and many, many drawings of Charles Manson. Though his thoughtful, guarded demeanor can make him seem like a naïf or some kind of addled savant, Pettibon is very much in on the joke. More so, usually, than anyone else. In The Art of Punk, former Black Flag singer Henry Rollins put it simply: “He was such a manipulator. He knows what’s going to cause a ripple and cause unrest.... It’s not gonna bring people to the show. It’s gonna get us beat up.”

Pettibon on Black Flag LP covers, from left: My War and Slip It In (both 1984)

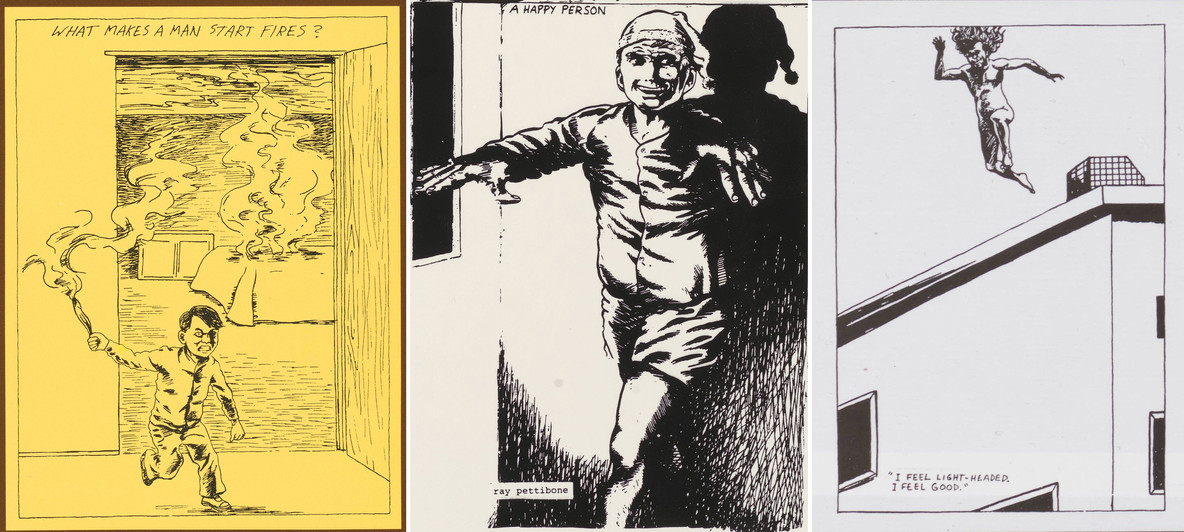

His work with Black Flag soon extended to his brother’s record label, SST, where—though he never became the official art director, like Peter Saville at Factory or Vaughan Oliver at 4AD—Pettibon’s album art and ephemera came to define the label’s visual identity. From 1978 until around 1985, Pettibon’s drawings adorned multiple SST compilation covers, not to mention LPs and singles for the Minutemen and Saccharine Trust. His friendship with Minutemen bassist Mike Watt may explain why the band’s albums often featured Pettibon’s drawings in their complete form, with both image and text: snippets of prose, broken aphorisms, oblique affirmations. Some sprang from his own head, while others were pulled from the thousands of books in his parents’ home.

Pettibon drawings on Minutemen LPs, from left: the cover image of What Makes a Man Start Fires? (1983), a detail from the back cover of Buzz or Howl Under the Influence of Heat (1983), and a detail from the gatefold of Double Nickels on the Dime (1984)

Raymond’s a great fan of irony. At the same time he has a very wry, and maybe a little dry, sense of humor.

Mike Watt, Raymond Pettibon: A Collection of Lines

The reunion of Pettibon’s own text—which is often missing or covered over on Black Flag materials—with his drawings reveals the enigmatic, haunting quality of his work, something far more compelling than mere adolescent provocation. In A Collection of Lines, Mike Watt shows a talent for understatement when he points out that “Raymond’s a great fan of irony. At the same time he has a very wry, and maybe a little dry, sense of humor.” But Black Flag’s continued willingness to literally paper over this more literary humor would play a role in Pettibon’s eventual split from SST and a lengthy hiatus from using his work on album sleeves in general.

A playlist of sounds behind some of the iconic album art of Raymond Pettibon

In the ensuing years, Pettibon ranged from circumspect to outright dismissive about his own place in, for lack of a better term, punk history. His disdain for the “scene” is played for laughs in his 1989 video Sir Drone, about the formation of an ostensible punk band (whose members include the artist Mike Kelley, sporting an “I’m Mellow” T-shirt, and Mike Watt). Despite their quasi-musical ambitions, all these clueless wannabes do is sit around badmouthing hippies and poseurs and, in a sly reference to Pettibon’s christening of Black Flag, argue about their band’s name: “You didn’t like The Abraham Lincoln Youth Brigade, did you? What about Chairmen of the Bored, as in boring? How ‘bout The Men from P.U.N.K.L.E?”

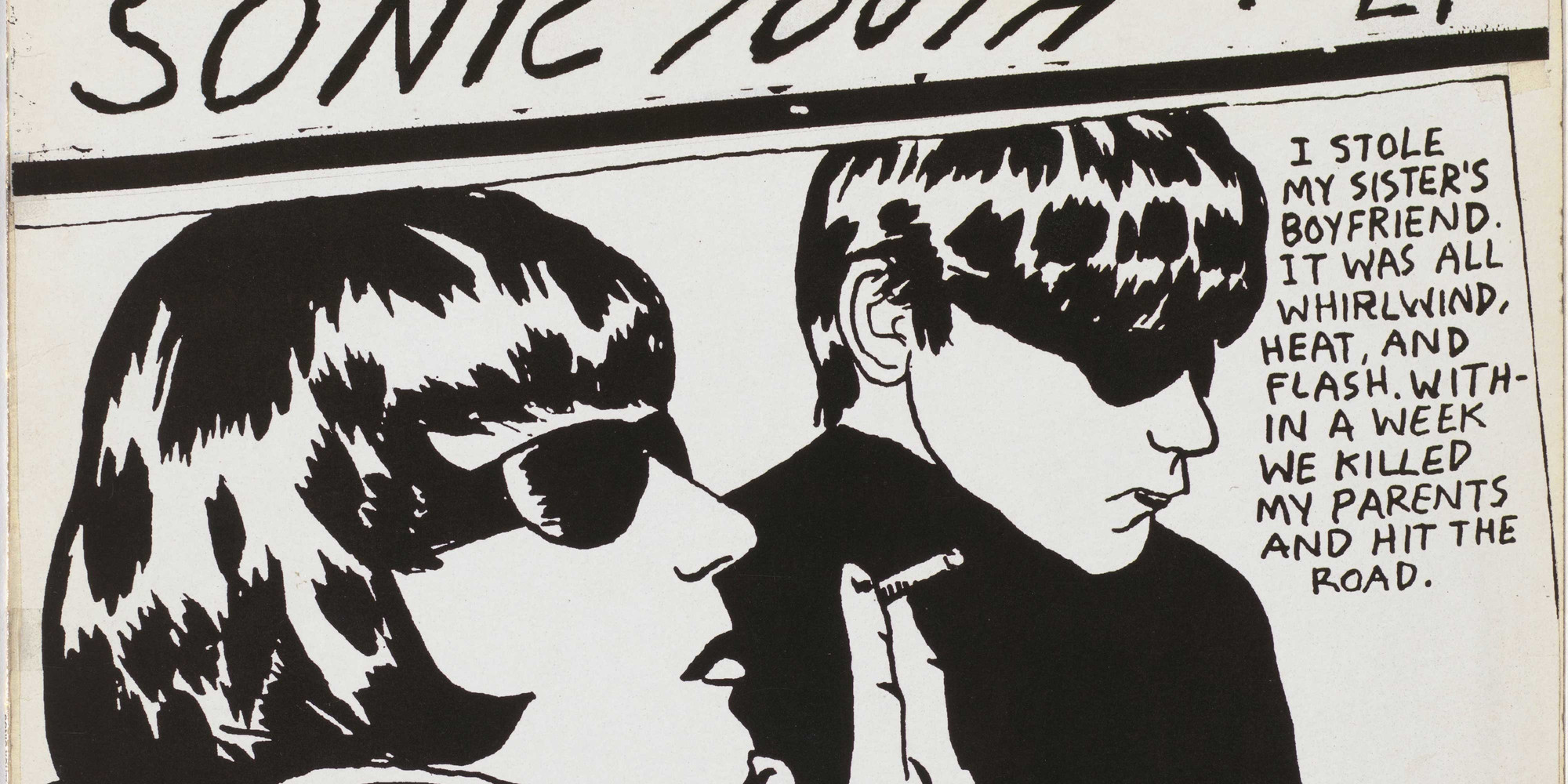

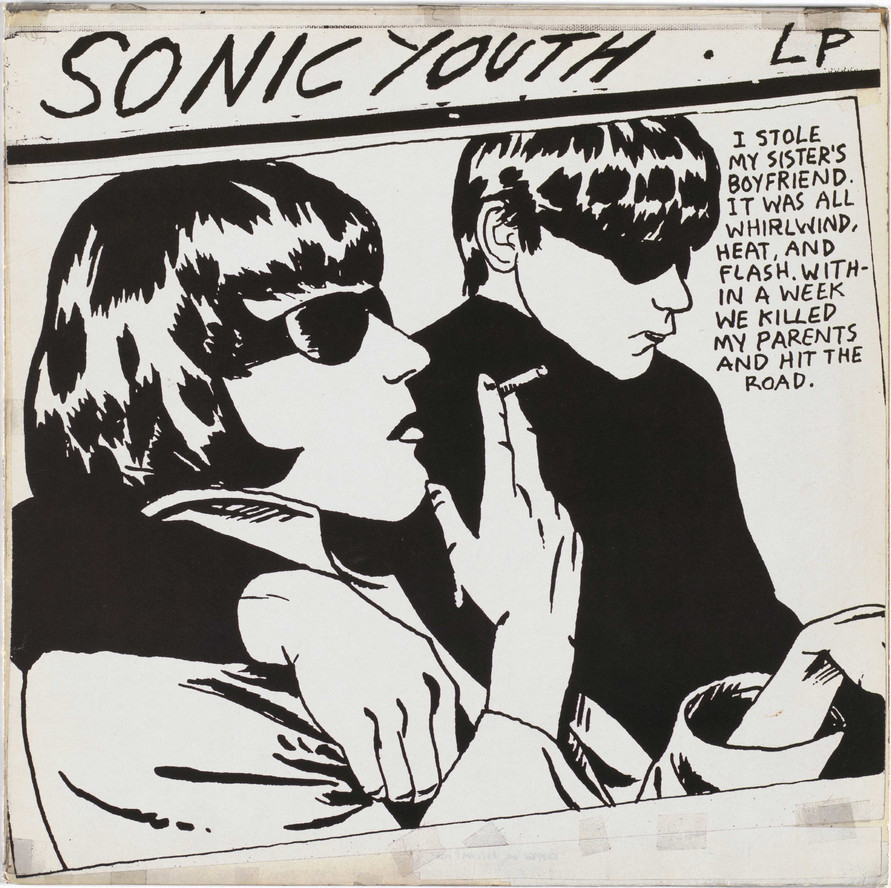

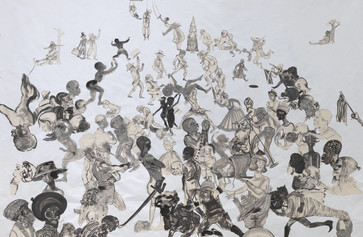

Ironically, this cinematic statement of music-biz ambivalence was almost immediately followed by Pettibon’s most iconic album cover, for Sonic Youth’s 1990 major-label debut, Goo. (When the record company balked at the band’s original title, Blowjob?, they renamed the album after a character in Sir Drone.) Yet although Sonic Youth had once been an SST band, working with them was light years from the South Bay punk scene: Sonic Youth bassist Kim Gordon’s art-world bona fides were well established, and their album sleeves had previously featured images by the likes of Gerhard Richter and Richard Kern (a roster that would later include Mike Kelley and Richard Prince).

Sonic Youth’s Goo (1990)

It’s safe to say that Goo represents the apotheosis of Pettibon’s career—however reluctant—as a rock ’n‘ roll artist. His text is high pulp: “I stole my sister’s boyfriend. It was all whirlwind, heat and flash. Within a week we killed my parents and hit the road.” The tongue-in-cheek cool is heightened by what we assume are the lovers on the run, looking bored in sunglasses and cigarettes. And yet Pettibon’s macabre streak lurks just beneath the surface, as the drawing is based on a real photo of Maureen Hindley and David Smith, who were on their way to testify at the trial of Myra Hindley and Ian Brady, perpetrators of the UK’s infamous Moors murders.

A still from Raymond Pettibon: A Collection of Lines, which premieres at MoMA on February 7

I borrowed my drawing style from the comic books because I’m not motherfucking Michelangelo, okay?

Raymond Pettibon, A Collection of Lines

Given the more collaborative nature of his work with Sonic Youth, not to mention the fact that Nirvana-besotted record labels started throwing corporate money at every indie band they could find in the early 1990s, it’s a bit surprising that Pettibon’s work didn’t appear on more records after Goo...but only a bit. With a few notable exceptions—including Mike Watt’s first solo album in 1995 and some Foo Fighters covers—he has remained wary. In a 2001 interview with Dennis Cooper, Pettibon zeroed in on the problem with being associated with something he’d never claimed as his own: “Whenever I’m asked to talk, everyone wants to talk about rock ‘n’ roll. I’ll do that if I don’t have to bring my art into it. It just shows the obsession society has with rock music and rock culture, nowhere more so than in art.”

Far from snobbishness, this is the attitude of an artist who, while aware of his own limitations (“I borrowed my drawing style from the comic books because I’m not motherfucking Michelangelo, okay?”), doesn’t want to serve life locked behind four black bars.

Raymond Pettibon: A Collection of Lines screens at MoMA on February 7 and 14 as part of this year’s Doc Fortnight festival. A selection of records in MoMA’s collection—including albums by the Minutemen, Blag Flag, and Sonic Youth featuring Pettibon’s art—are currently on sale as part of the Record Shop pop-up at the MoMA Design Store, Soho, through March 1.

Related articles

-

Record: The Space Between

MoMA’s record label reissues Antonio Dias’s unconventional—and only—audio project.

Lilian Tone

Dec 23, 2019

-

The Way I See It

Roxane Gay on Kara Walker

Culture writer Roxane Gay describes the importance of sitting with discomfort in front of Kara Walker’s drawing.

MoMA

Dec 2, 2019