24 hours with Matthew Ritchie

Artist Matthew Ritchie spends a day in between worlds.

Matthew Ritchie

Sep 30, 2019

This feature is part of our A Day series, in which writer Heidi Julavits invites artists to share an account of their day with us.

Click on the image to get a closer look.

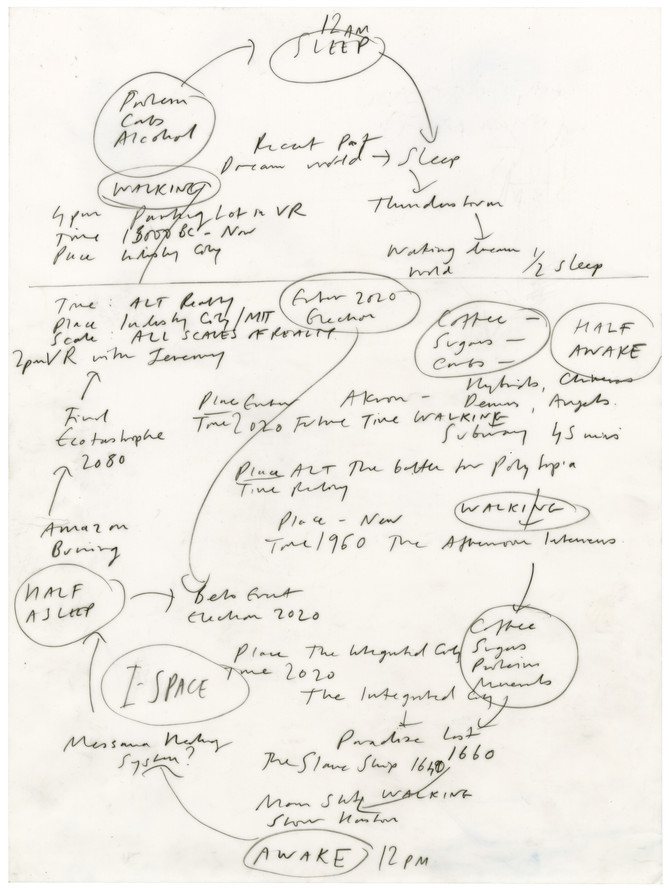

DIAGRAM 1

I did this one first and then I thought, “This is not interesting. This is just a flow chart of a day.” I have a friend who did a study of cell phone use and they found you could predict where people are going to be 93% of the time. And in that mostly predictable 93%, your brain and body are narrating the ordinariness of your life, convincing yourself the day happens in a plausible sequence, making excuses for the horror show. “Yeah, this is cool. We’re going to have some sugar, some carbohydrates, some caffeine, and take the subway.” That’s the story your brain is basically happy with.

Click on the image to get a closer look.

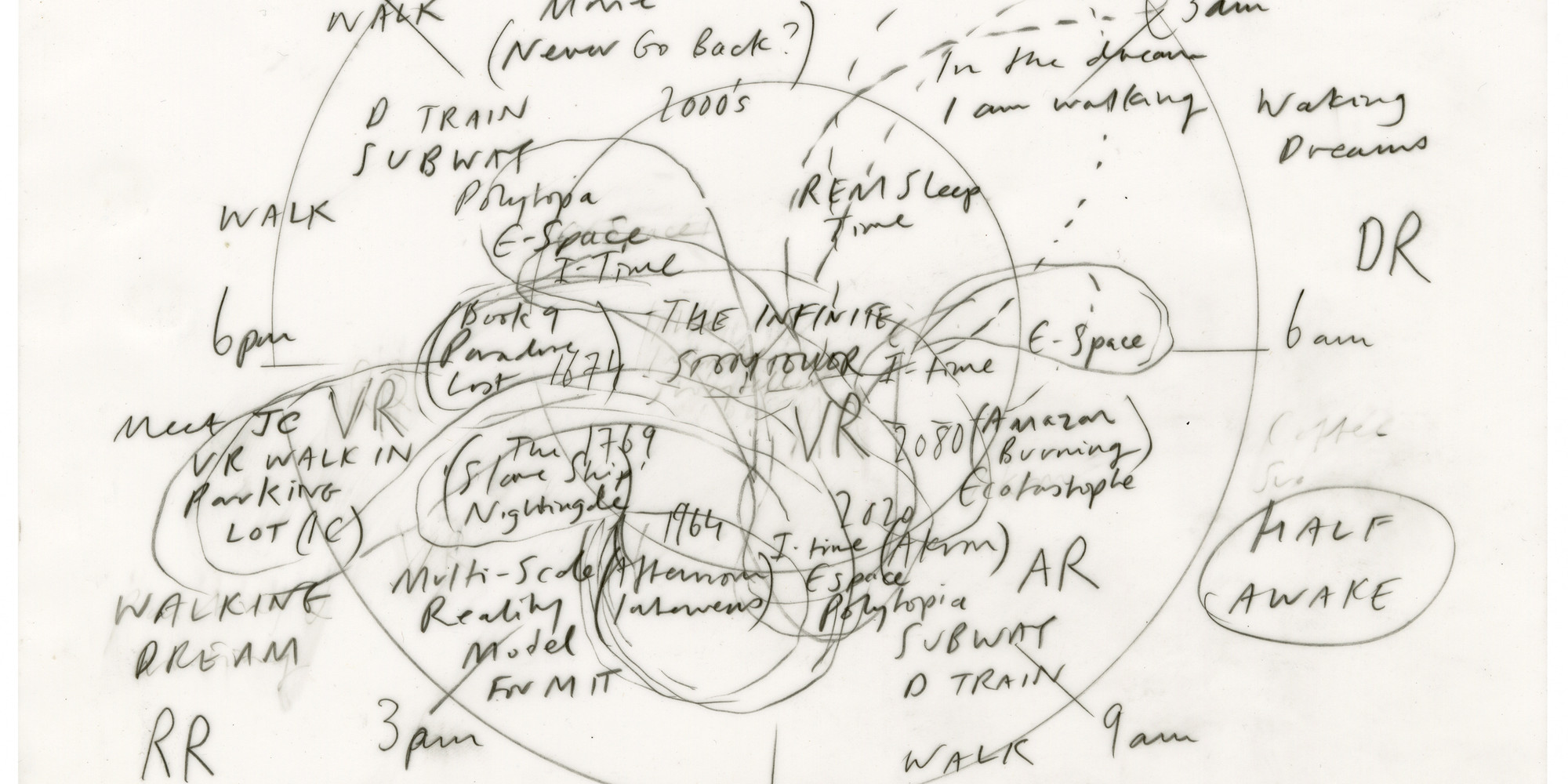

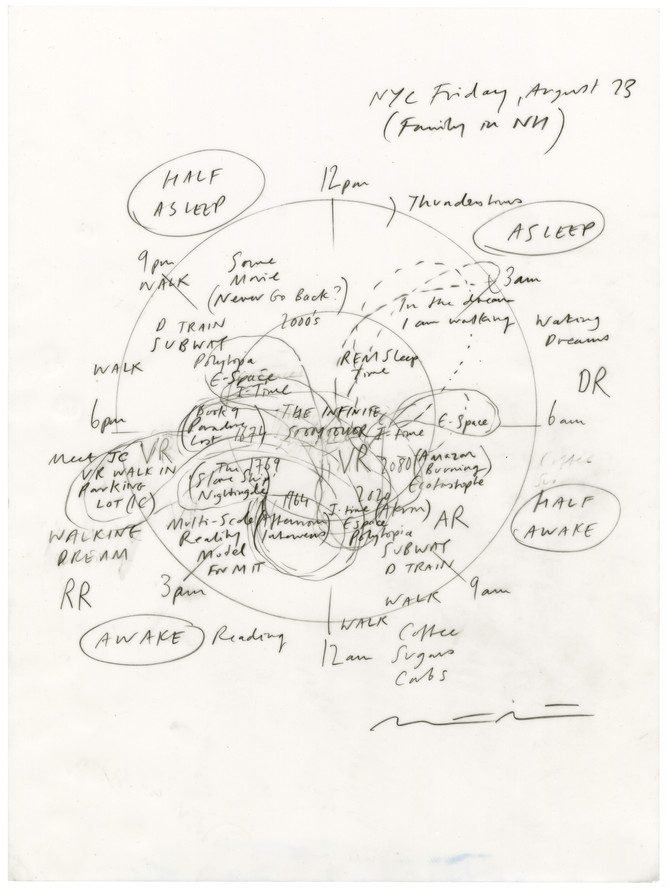

DIAGRAM 2

But then there’s the 7% left over, the chaos that makes life interesting—the “What the fuck is really going on?” This second diagram is a 24-hour clock divided into three concentric rings, with these kind of tongues, or tunnels connecting them. This is what I think the leftover 7% is really up to; this terrible, beautiful, chaotic business, turning itself inside-out, over and over again.

THE WEATHER

I think what started the day was the thunderstorms. I remember that between 12:00 and 3:00 a.m. there were these massive, massive summer storms. I remember feeling their presence in a kind of waking dream—and it affected the whole day.

THE THREE RINGS

The outermost ring is the real, physical world and the things that are happening in that world. On the outside of the ring, it says “half asleep,” “asleep,” “half awake,” and “awake.” In the morning, you’re drinking coffee, you’re walking—even while you’re only half awake.

THE SUBWAY

The middle ring is all the in-between worlds when you’re in artificial spaces, like cars, or the subway, or reading your email, or reading about the Amazon, which was burning that day, or on the subway reading about the Amazon burning. You’re somewhere else at the same time as you are in your body, not just completely inside your head; dreaming even while you are awake. Someone might be right beside you reading a Chinese-language newspaper on their phone and reading the same news story as you about the Amazon burning—or playing Candy Crush. As a counterbalance to the news and email on the subway, I play The Battle for Polytopia, a kind of idiotic AI chess blended with Minecraft, which I find endlessly engrossing.

ELECTRONIC SPACE (E-SPACE) v. INFORMATION TIME (I-TIME)

Electronic space is the space that you’re in while you’re looking at your phone. But the informational time it takes you to read and process something in E-Space is really different to the amount of space-time it takes up in the real world. You can go anywhere instantly in I-Time. If I read, “The end of the world is in 2080”—the end of life on Earth, when the Amazon forest finally burns down, pretty much when the climate change catastrophe becomes totalized—you can get there in time right away. It doesn’t take 60 years. So on this particular day I visited 2080, then 2020 for the elections, then 1964 because I was reading the Duchamp interviews with Calvin Tomkins, and then 1769 because I was reading The Slave Ship by Markus Rediker and it was really under my skin that day. Slaves would use the entire body of the ship like a musical instrument, they would beat it or stamp their feet to communicate messages, because they often didn’t share a common verbal language. And then 1764, for Paradise Lost, because in some sense I am always there. Obviously this fusion of human imagination and technology is a huge, new, and interesting problem.

The center ring is the inside world, where things seem to be happening totally internally. It’s the place you go in the back of your mind when you dream.

What I loved about this whole idea was asking myself, how many times a day do you go in and out of all these different spaces and times? The answer for me, apparently, is a lot.

THAT DAY

This day had one particular event when something broke through all three rings. I’d been thinking about building a model of the universe in VR that’s only going to be visible inside a part of the MIT campus and we hoped we’d found a way to walk around freely in the real world and be in VR at the same time. The first test of this idea was that day. So it’s Friday, and I’m walking around in the parking lot outside my studio in New York, but I’m also inside a model, of part of MIT, a place that’s hundreds of miles away—that itself contains images of a much larger universe—and I’m also deep inside a waking dream, my own inner circle, built in E-Space and I-Time, loaded into a real artifact that you can put on your head, pushing it all the way out into the real world from the inner one.

Related articles

-

A Day

24 hours with Howardena Pindell

On a Sunday in the studio, artist Howardena Pindell weathers a summer storm with us.

Howardena Pindell

Aug 29, 2019

-

A Day

24 hours with Xaviera Simmons

Xaviera Simmons shares an intimate day of rituals, images, and thoughts on America's construction through white supremacy and capitalism.

Xaviera Simmons

Aug 16, 2019