Distilling Martha Graham’s Dance in Photographs

A remarkable book explores the collaboration between the modern dance innovator and the photographer Barbara Morgan.

Rachel Rosin

Jul 1, 2024

“It is rare that even an inspired photographer possesses the demonic eye which can capture the instant of dance and transform it into a timeless gesture,” Martha Graham reflected in 1980. “In Barbara Morgan I found this person.”1

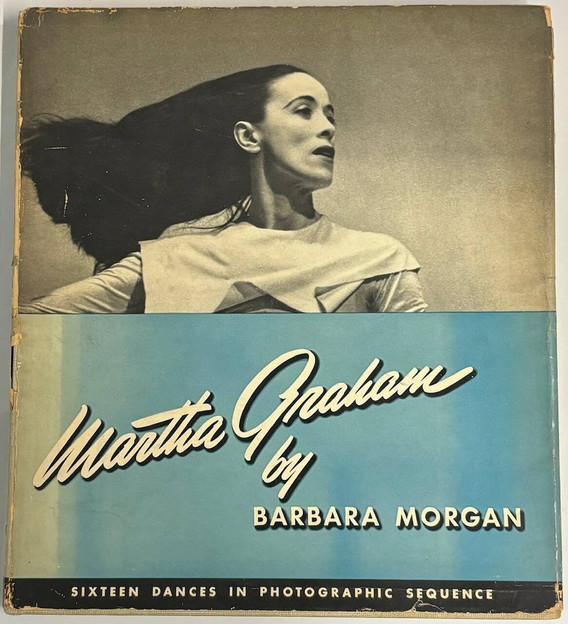

Some 40 years earlier, the two women had begun to work together on a collaborative photobook titled Martha Graham: Sixteen Dances in Photographic Sequence, which was first published in 1941.2 Each segment, featuring Morgan’s photographs, highlighted one of 16 dances Graham selected as the most significant in her career up until that moment. This remarkable photobook is now on view in Gallery 409: Dance Index, alongside works by Harry Callahan, Yasuhiro Ishimoto, Shirley Clarke, and others.

After seeing Graham perform in the mid-1930s, Morgan decided she wanted to document her dances, immediately recognizing Graham as a trailblazer in the emerging field of modern American dance. Soon after, the two embarked on what would become a six-decade relationship—as co-authors, dancers, photographers, and close friends.

Cover of Martha Graham: Sixteen Dances in Photographic Sequence, by Barbara Morgan and Martha Graham

Morgan abandoned her tripod and turned to the adaptable Speed Graphic 4 × 5 camera, which allowed her to move along with each of Graham’s movements—both choreographer and photographer dancing for the camera.

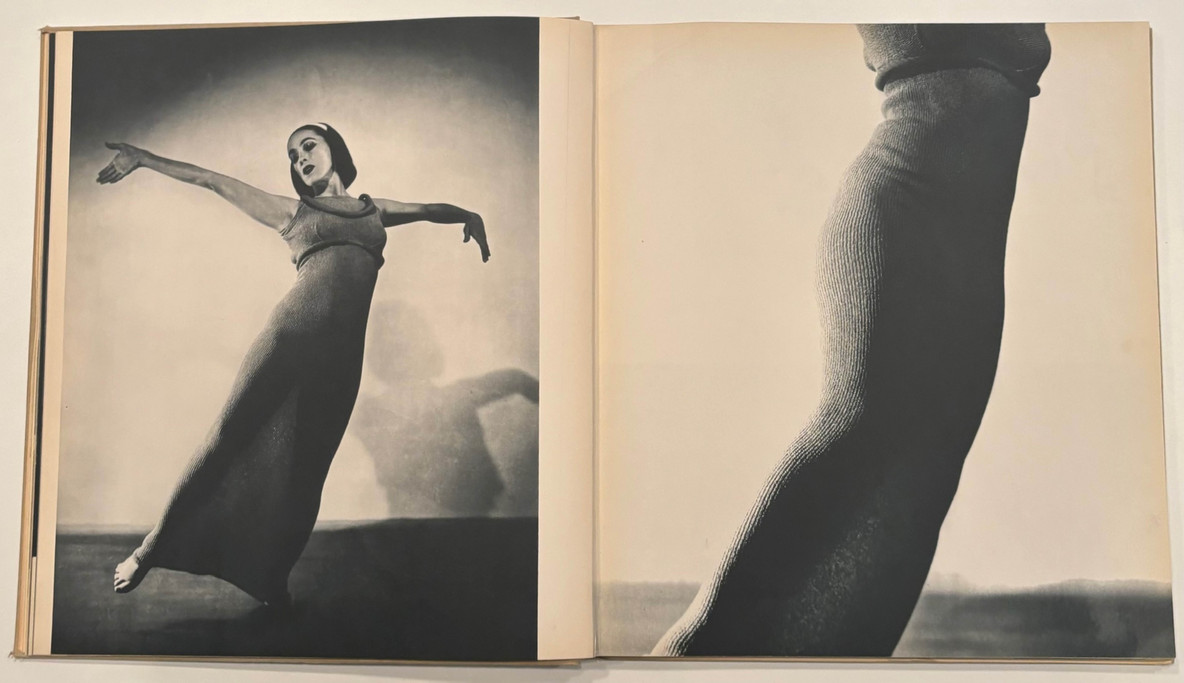

Barbara Morgan, Martha Graham, Extasis. 1935

To create each photograph, Morgan would first absorb each dance—watching hours of studio practices, exercises, dress rehearsals, and live performances, and listening to the accompanying music.3 She would then distill a dance into a few essential gestures or themes.4 It was during this period that Morgan abandoned her tripod and turned to the adaptable Speed Graphic 4 × 5 camera, which allowed her to move along with each of Graham’s movements—both choreographer and photographer dancing for the camera.5 “We’d chant together, 1-2-3, or whatever, so we’d get in rhythm together,” Morgan described. “Then I would put chalk where the moment was and then I’d get the camera.”6

The third of the 16 dances in the photobook, Ekstasis, emerged from Graham’s revelation of the “pelvic thrust”—a gesture which became crucial to her artistic lexicon. Graham described the moment of revelation that took place in her Ninth Street studio:

I was alone and working and suddenly I discovered the pelvic thrust. I felt it was very important. It was the basis of Ekstasis, and the beginning of a cycle of distortion, not for distortion’s sake but for deeper meaning and feeling. Before Ekstasis, maybe I had been using a more static form, trying to find a ritualist working of the body. This new discovery led me to what I am today, to the technique.7

Ekstasis is the result of Graham working out the mechanics of her technique—through bodily contractions, shifts, and “distortions.” The pelvic thrust configures Graham’s famous concept of contraction and release—defined as the exhalation of breath (the contraction) and the inhalation (the release)—originating from the deep pelvic muscles.8

To make this photograph, Morgan sought to do more than, as she put it, “fortuitously record.”9 Instead, she thought it necessary “to redirect, relight, and photographically synthesize” in order to achieve what she felt to be “the core of the total dance.”10 Morgan photographed Graham not during her live performances, but instead held her photographic sessions at locations across the city—at the New York Guild Theater, Columbia University’s McMillan Theatre, the Henry Street Settlement Playhouse, and Morgan’s own studio overlooking Madison Square. In these controlled settings, Morgan could manipulate the lighting, timing, composition, and sequencing of each photograph.

“Light is to the photographer what movement is to the dancer,” Morgan wrote, “the active principle without which there can be no photograph, as without movement there can be no dance.”11 Morgan used overhead and back lighting to create an interplay of light and shadow, allowing for psychological overtones, architectural framing, or a sculptural modeling of the figure that would free it in space.12 The resulting photograph “epitomizes my feeling for the dance,” Morgan later reflected, “the side and back lighting frees and solidifies the sculptural form; the tonal shift of the triangle of light projects distance and supports a rhythmical monumentality.”13 Light accents and abstracts Graham’s body, creating a serpentine shape. Morgan’s cropped image reveals only her torso, severing the dancer’s head, neck, arms, calves, and feet from the frame, just as Graham thrusts—and so too “distorts,” as she describes it in her revelation of the pelvic thrust—her own body in dance.

Ekstasis, full spread in Sixteen Dances (1941)

Mimicking the dancer’s movements, the reader is thrust forth from one photograph into the other.

“Such work is a kind of translation,” Morgan wrote in the introduction to Sixteen Dances. “The picture-page relationships serve as a bridge between two mediums: Dancing and Photography. They communicate to the seeing reader the intense reality of movement contained in the original dance.”14 In Sixteen Dances, Morgan translates Graham performing Ekstasis into a two-page photographic spread, juxtaposing her body photographed at full length and the cropped torso composition. In the first photograph, Graham’s left arm is in the classical second position while her right arm sweeps above as she balances on her left foot, pointing her right toe away from her body. Graham is wholly expansive: rib-cage stretched, arms lengthened, jawline extended and toes pointed out. The next page is the fragmented close-up of her body: a contracted torso, pelvis, knees, and angular legs. The shift from the wide shot (the release) to the zoomed-in shot (the contraction)—and from one page to the next—echoes Graham’s pelvic thrust. Mimicking the dancer’s movements, the reader is thrust forth from one photograph into the other. Morgan was interested in pictorial juxtapositions and their potential to shift photographs beyond their function as singular images. “The serial presentation,” she wrote in an article titled “Juxtapositions in Photography,” “builds the total form and meaning.”15 In Sixteen Dances, the two photographs are presented in serial arrangement, one following the other, imbuing the object of the book with motion—and speaking to the very act of “translation” that Morgan describes.

Barbara Morgan. Martha Graham, Celebration. 1937

-

Barbara Morgan, Martha Graham: Sixteen Dances in Photographs, 1st revised ed. (New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce; Dobbs Ferry, New York: Morgan & Morgan, 1980).

-

Barbara Morgan, Martha Graham: Sixteen Dances in Photographs, 1st ed. (New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1941).

-

Suzanne Dechillo, “Barbara Morgan: The Photographer of the Dance,” The New York Times, January 14, 1979.

-

“Dramatizing the Dance: Interview with Barbara Morgan.” Dance Life 14 (1979): 44.

-

Anna Kisselgoff, “Dance View. Powerful Images of Martha Graham’s Art,” review of Martha Graham: Sixteen Dances in Photographs, by Barbara Morgan, 1980 Ed. The New York Times, November 23, 1980, 24.

-

For more on Graham’s technique, see Blakeley White-McGuire, The Martha Graham Dance Company: House of the Pelvic Truth (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022).

-

Barbara Morgan, “Learning Experiences — Working Thoughts.” Aperture, Spring 1964: https://issues.aperture.org/article/1964/1/1/learning-experiences---working-thoughts.

-

Barbara Morgan, “Juxtapositions in Photography.” In The Encyclopedia of Photography: The Complete Photographer. Vol. 10, 1896–1905 (New York: Greystone, 1963).

Related articles

-

Dream in the Rhythm

Read Grace Wales Bonner’s introduction to the book that accompanies the exhibition Artist’s Choice: Grace Wales Bonner—Spirit Movers.

Grace Wales Bonner

Nov 13, 2023

-

Lincoln Kirstein, Writer

A glimpse into this 20th-century tastemaker’s literary world

Elizabeth Welch

Mar 28, 2019