Fishing Nets Catch a Collective Vision of Harmony with Nature

MoMA’s soaring atrium is filled by the beauty of Carolina Caycedo’s sculptures—and the scale of our environmental challenges.

Carolina Caycedo, Inés Katzenstein

Jan 5, 2024

Spiral for Shared Dreams, an installation by Carolina Caycedo in MoMA’s Marron Atrium, comprises an ensemble of handmade fishing nets, created by four communities in Mexico facing environmental challenges, in which Caycedo intervenes with color and embroideries. Recently we spoke with Caycedo about Spiral for Shared Dreams, the connection between art making and activism, and art’s ability to make us remember.

—Inés Katzenstein, Director of the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Research Institute for the Study of Art from Latin America and Curator of Latin American Art, Department of Drawings and Prints

Este artículo está disponible en español.

Carolina Caycedo: Spiral for Shared Dreams is part of a series titled Cosmoatarrayas, which itself is part of a larger body of work called Be Dammed, or Represa Represión in Spanish. Cosmoatarrayas combines the word “cosmos” and atarrayas, which is the Colombian Spanish name we give to round, artisanal fishing nets. They are used by various cooperatives and collectives that I’ve been in conversation with as part of my fieldwork. I look at how rivers, communities and ecosystems are affected after an extractive infrastructure, like a hydroelectric dam, is constructed in their land.

The nets are sourced from individuals and collectives on the front lines of these environmental struggles. I bring them into the studio and alter them in playful ways by dyeing them and giving them different forms. I worked on this particular project with four Mexican fishing cooperatives; two of them are women’s fishing co-ops. Normally I would have spent time with collaborators in their territories, but in this case we communicated via phone calls and texts because we were in the midst of the pandemic.

One of the women’s cooperatives, Mujeres Pescadoras del Manglar, in Oaxaca, fished in the saltwater lagoons on their land. Without consulting the local community, the government built a concrete breakwater that stopped the flow of water and oxygen, cutting off the lagoon from the rest of the marine ecosystem and affecting the fishing adversely.

Carolina Caycedo: Spiral for Shared Dreams at MoMA

Spiral for Shared Dreams

The other women’s cooperative is Sociedad Cooperativa Mujeres del Golfo, in Baja California Sur. They dive and catch small ornamental fish; they’ve been doing this for generations. The women I am in contact with are the daughters and nieces of the group’s founders; they’ve had to struggle to find their place in a very masculine, patriarchal fishing community.

I also worked with a cooperative from Nayarit called Sociedad Cooperativa del Norte. They also have issues with lagoons and estuaries on their land. They fish for shrimp and other crustaceans. They fish at night and their nets have veins that allow them to compress. This was actually the first time I’ve worked with these kinds of shrimp-fishing nets.

The last cooperative is Comite Salvemos Temaca, Acasico y Palmarejo, in Jalisco, a fishing and subsistence farming community that was impacted by the construction of El Zapotillo Dam on the Rio Verde.

So these four cooperatives, which find themselves in similar situations, shared their fishing dreams and fishing nets with me. For me, this project is about feeding and nurturing an existing network of people. I get in touch and work with these communities as a way of strengthening political solidarity and environmental empathy.

Our conversation often starts with me sharing previous sculptures and extending a straightforward prompt: “Hey, I’m looking for fishing nets to create sculptures to go in a museum.” And I send pictures of previous works. Then comes the process of discussing whether there’s someone who still weaves nets, what kind of nets they have available, and who might be willing to make a net for the piece.

During this process there is an intimacy that happens. For example, Carmen Cota leads the women’s cooperative from Oaxaca. When we had our conversations during the pandemic, we were both pregnant and then had babies at almost the same time. So that intimacy started to weave itself into the piece. And she asked, “When are you coming to visit?” So now I have an invitation to visit her, and am excited to go.

When you examine it, the fishing net is the opposite of an infrastructural construction, such as a dam. The dam is this impermeable, monumental, gargantuan, corporate, industrial design that stops the flow of water and cuts the body of a river in two.

On the other hand, a handmade fishing net exists on a human scale. It’s porous, flexible, malleable, and captures sustenance while letting water through. It breaks with use but can be repaired. And even if one of the knots is untied, it doesn’t compromise the function of the whole structure.

Spiral for Shared Dreams

Spiral for Shared Dreams

I imagine if there's a crack in a dam, it can collapse. Which can be understood as the collapsing of a system. Our societies would function much better if they were structured and designed more like a fishing net than a dam. Instead of building more walls, we should be building more systems that adapt to a situation and are porous, changeable, and able to be rearranged.

Even installing these works here at MoMA has been a beautiful process, because during installation we had to rearrange some things and play with the pieces in this space. I want to make work that can be reimagined every time it’s installed. This exhibition provides different entry points to different kinds of audiences; I’m invested in making art that is legible and accessible. Something that has surprised me about showing the fishing nets in different museums and contexts is that there are a lot of people who recognize the nets because they used to fish when they were children or they had a family member who fished. At the exhibitions, many of them encounter that artisanal fishing is still something that’s being embodied. So I hope these nets make folks remember their connection to this subsistence practice, and the fact that they still have this memory means they can still take up this practice.

Or at least remember it. This act of remembering, I think, is very important. Also, in the context of climate change, it is more important than ever to remember how we used to interact with the rivers, how we connected to other species like fish, and how we went as a group or a family to fish together. So being able to spark these memories is one of the most important things to me.

Below are quotes from the members of the four communities Carolina Caycedo worked with to create Spiral for Shared Dreams

“I am Cristina Emperatriz Arellane Martínez, and I am a member of the Zapotalito Tututepec Juquila community in Oaxaca, Mexico. I belong to the Mujeres Pescadoras del Manglar cooperative. In 2003 the government launched a project to repair the breakwater, but it was poorly done and ended up damaging our lagoon. A great many fish were killed because the flow of water that connected the lagoon to the sea was cut off. So sad. You ask, ‘How can I help?’ I think by raising your voice. That is what we are trying to do—to envision something different as women and as a cooperative. To pass valuable lessons down to the next generations.”

“My name is Brígida Martínez Ávila, and I am part of the Zapotalito Tututepec Juquila community in Oaxaca, Mexico. I am a member of Mujeres Pescadoras del Manglar, a cooperative that monitors the quality of the water (its temperature, pH, oxygen saturation, etc.). My job at the cooperative is to make sure everything goes as planned, to track compliance with agreements, and to work with and for the people—to take care of what we have around us.”

“The problem facing us is the water contamination from the pesticides used for crops these days. It will do away with everything we have. That is why I became part of the Salvemos Temaca, Acasico y Palmarejo committee: to provide support and fight to defend the people.”

José Jesús Gómez Franco

“I am José Jesús Gómez Franco, and I am from Temacapulín, Mexico. I am the creator of some of the atarrayas that were exhibited at the Museo Universitario del Chopo in Mexico City and are now on view at The Museum of Modern Art in New York. I work the land and sell what it produces, mostly chili peppers and peanuts, hence the atarrayas.

I learned to weave atarrayas by seeing how it was done and asking questions. I really taught myself how to weave them when I was 16 years old. The problem facing us is the water contamination from the pesticides used for crops these days. It will do away with everything we have. That is why I became part of the Salvemos Temaca, Acasico y Palmarejo committee: to provide support and fight to defend the people.”

“My name is Carmen Cota, and I live in the Ligüí community in the city of Loreto, Baja California Sur, Mexico. I am the current president of the Sociedad Cooperativa Mujeres del Golfo. It was founded by my mother and grandmothers. It was very difficult at the beginning, because a number of men opposed a cooperative of women. Until recently, they would call us las golfas because they didn’t like that we would go out fishing. I said to the women, ‘There is no turning back. We must keep at it, keep up the fight.’ Our most important struggle was to gain equal representation of women in the fishing sector.

We harvest tropical fish, fish for fish tanks. The way we do it is pretty low impact. We attach nets we make ourselves to a small funnel. They look like the nets used to catch butterflies. When we can, we fish with our hands. These are good practices that take care of the environment. Normally, men and women fish together. We now have four divers certified to fish in deep waters.”

“My name is José Ignacio Herrera Montaño. Since 1991, I have belonged to the Sociedad Cooperativa Norte de Nayarit in the city of Tecuala, Nayarit, Mexico. We work in ponds and saltwater lagoons. The bulk of our catch is shrimp. The craft of fixed-gear fishing we practice here makes use of atarrayas as well as a kind of trapping structure that keeps the shrimp from escaping into the sea. We fish at night when the tide is low. We use lanterns to attract the shrimp. We buy some of the nets, but others are woven in nylon or silk by five members of the organization.”

“My name is Gabriel Espinoza Íñiguez. I have been the spokesperson of the Comité Salvemos Temaca, Acasico y Palmarejo since 2008, and the director of the nonprofit organization Salvemos Temaca since 2010. We have been doing the very difficult and also very beautiful work of defending the land from El Zapotillo Dam. I struggle to keep regional economies afloat. I fight for fair trade, for farming, fishing, and animal rearing—work with Mother Earth (some call her ‘Sister Earth,’ ‘Sister Water,’ or ‘Sister Nature’) in the true peasant sense of the word.

I remember a photo of my granddad weaving an atarraya. That is why it is a special honor for me to be part of bringing the nets from a community as small as ours to museums and thus giving many more people an idea of what is happening in this corner of the world.”

Carolina Caycedo: Spiral for Shared Dreams is on view at MoMA through May 19, 2024.

Related articles

-

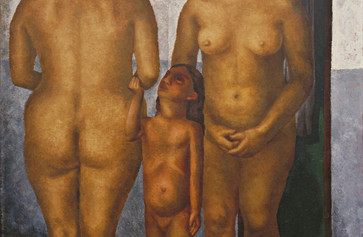

“The Aunts” by Carina del Valle Schorske

Read a poetic exploration of identity, family, and legacy inspired by Julio Castellanos’s painting.

Carina del Valle Schorske

Oct 13, 2023

-

New to MoMA

Christina Fernandez’s María’s Great Expedition

The artist uses family lore to examine the meaning of migration.

Lucy Gallun, Christina Fernandez

May 31, 2019