Emerging Ecologies: Introduction to a Field Guide

Read an exclusive excerpt from the exhibition’s “field guide,” in which the fervor that led to the first Earth Day acted as a backdrop to architectural innovation.

Carson Chan

Sep 11, 2023

In their 1971 book Shape of Community: Realization of Human Potential—published a year after the US Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act and the Nixon administration established the Environmental Protection Agency—the architects Serge Chermayeff and Alexander Tzonis presented the history of the world as a series of evolving “ecologies.” The authors argued that if the “first ecology” was that of the oceans—the place of life’s origin—and the “second ecology” was life on land, the “third ecology” began with the recognition that humanity now had the ability to alter the planet: that “the man-made and the natural are now inseparable.”1 The word ecology and its popularization through the writing of ecologists Eugene and Howard Odum is never fully described in the book. But if we take it to mean both the totality of interconnected relationships between various organisms and their physical environment and the branch of science devoted to the study of these connections, the history of how humans live, shelter themselves, and modify their surroundings is the history of emerging ecologies—of places humans shape and that shape them in return, and of the knowledge that has been gained and lost in this multimillion-year process.

Cover of Serge Chermayeff and Alexander Tzonis, Shape of Community: Realization of Human Potential (London: Penguin, 1971)

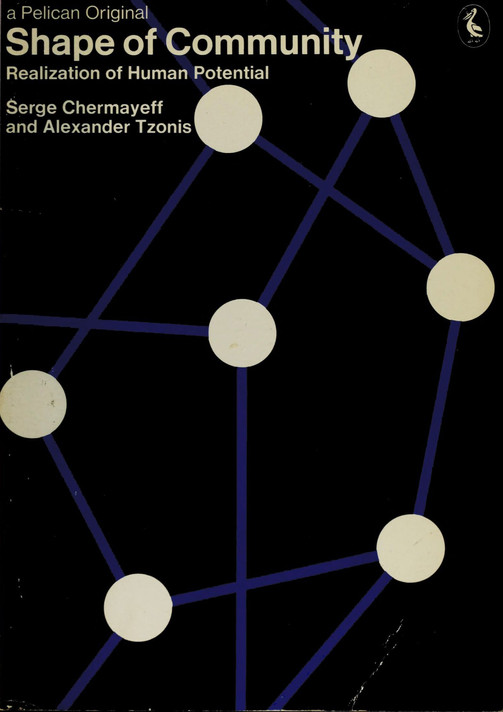

Harshaw Chemical Company discharges waste water into the Cuyahoga River, 1973. United States National Archives and Records Administration. Records of the Environmental Protection Agency. Photo: Frank J. Aleksandrowicz

More than 500 years since the beginning of the European colonial project that signaled the modern era of mass resource extraction, 200 years since the arrival of the Industrial Age that mechanized and accelerated this process, and 50 years since the UN conference in Stockholm on the need to coordinate environmental management and protection across the globe, we find ourselves today at a moment of both terrifying man-made climatic challenges and galvanizing, life-affirming hope.2 Emerging Ecologies—a necessarily selective survey tracing milestones in the history of environmental thinking in American architecture during the rise of environmentalism in the United States—asserts this hope by showcasing the daring, incisive, and at times disruptive architectural proposals of the past, from whose rich, largely unexplored grounds new ecologies—new ways of living on this planet—may emerge. The exhibition’s focus on projects from the US and by those who made their careers in the US recognizes the cultural awakening to environmental issues in mid-20th-century American society. Architects, along with everyone else in the age of mass media, watched as 200,000 gallons of oil flowed into the ocean off the coast of Santa Barbara, California, for 11 days in January 1969 and, five months later, a chemical slick on the Cuyahoga River (which had been sporadically ablaze since 1868, when industry claimed its shores) in Cleveland burst into flames.

New York City Earth Day crowd, April 22, 1970. New York City Department of Records and Information Services. Courtesy Municipal Archives, City of New York

The crescendo of outrage at perceived governmental oversight of these problems led to the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970, during which 20 million people across the United States stood together against environmental ignorance. To be sure, this moment in US history acts as the exhibition’s framework, without suggesting any claim to American primacy or exclusivity to environmental awareness around the world. Furthermore, this brief introduction to the exhibition’s field guide does not delve into the groundbreaking contributions each project makes to the field of architecture, nor does it examine the intense intellectual exchanges that took place among their creators as they and the rest of society woke to the beginnings of the anthropogenic environmental crisis. Instead, this text tracks the exhibition’s historical lineage, before suggesting some of the larger implications its projects have on the way architecture itself is defined. In many ways, architecture is already an environmental discipline that didn’t realize it was one until quite recently.3 At present, architectural activity—more broadly the building sector—is the prime contributor to the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.4 The hope is that this book, as an inventory of the material in the show, will become a resource for those interested in tracing a new path for architecture that puts ecological and environmental concerns before all other considerations.

Want to read more? Pick up a copy of Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism.

The exhibition Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism is on view at MoMA September 17, 2023–January 20, 2024.

-

Serge Chermayeff and Alexander Tzonis, Shape of Community: Realization of Human Potential (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books, 1971), 8, 35.

-

Climate journalist David Wallace-Wells’s 2019 book all but dictated ways to make peace with humanity’s self-caused demise. But three years later, and after the edifying shock of a global pandemic, Wells writes with optimism of the aggregate of environmental awareness campaigns and education efforts that has led to an “astonishing decline in the price of renewables, a truly global political mobilization, a clearer picture of the energy future and serious policy focus from world leaders.” See David Wallace-Wells, “Beyond Catastrophe: A New Climate Reality Is Coming into View,” New York Times, October 26, 2022, and David Wallace-Wells, The Uninhabitable Earth: Life after Warming (New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2019).

-

See, for example, the recent pathbreaking environmental histories of architecture by Daniel Barber and Barnabas Calder. Daniel A. Barber, Modern Architecture and Climate: Design before Air Conditioning (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020); Barnabas Calder, Architecture: From Prehistory to Climate Emergency (London: Pelican Books, 2021).

-

2021 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Towards a Zero-Emission, Efficient, and Resilient Buildings and Construction Sector (Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme, 2021).