Ten Minutes with Emeka Ogboh: On Active Listening

A maker of multisensory artworks reflects on the importance of listening to our surroundings.

Emeka Ogboh

Jul 14, 2023

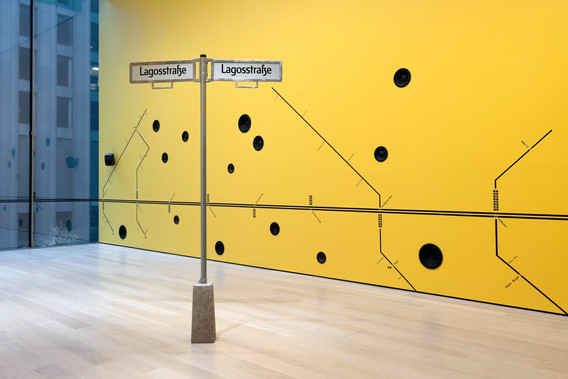

In 2014, Nigerian-born artist Emeka Ogboh moved from Lagos to Berlin. This experience marked not only a shift in his surroundings, but also a shift in his artwork. “Shuttling between two places,” Ogboh explains, “your brain has to do this switch. And that fusion of two places started occurring to me.” His immersive installation Lagos State of Mind III, currently on view in MoMA’s second-floor galleries, blends the experience of living in these two cities. It includes a sign for an imagined street called Lagosstrasse, and a layered soundscape composed of field recordings made in both cities’ public spaces.

We are saturated with sound—from birds chirping in the early morning to the boisterous laughter of a group of friends in the afternoon and the soft hum of an electric fan as we settle into sleep. Though we may ignore them, each of these sounds has a lot to say about our surroundings. “We always try to build this bubble around us,” says Ogboh. “I also do that. But I think we should unplug [our] headphones more, pay more attention to our space and know what’s going on.”

Emeka Ogboh. Lagos State of Mind III. 2017/2020

This World Listening Day—an annual celebration held on July 18—we invite you to explore your surroundings and reflect on how sound shapes our world through the SoundCloud link below.

See below for a transcript of the SoundCloud audio.

Artist, Emeka Ogboh: I think in 2011 I was part of a group show with African artists in Helsinki. And for this show, I had two installations: one inside the museum on headphones and one outside the museum on these speakers.

So I remember, we first plugged in the sounds for the outdoor installation and I went upstairs and I was working on the indoor headphone piece. And they called me like, “Oh, someone really wants to see you downstairs.” So I went downstairs, there was this young guy. And this guy, was very emotional.

So I was like, okay. What’s wrong? What’s going on? And he doesn’t know where to start, but you know, he’s been living in Helsinki two or three years. He’s a student. He has two jobs. Every day he walks up to this place and takes a bus.

But today, he’s coming up here. He’s hearing the sounds of Lagos.

So this guy, he’s looking around. He’s seeing himself surrounded by white people, like, up in Helsinki, but “I’m hearing the sound of Lagos.” He was very emotional. So he called his friends, “You can’t even imagine what I’m hearing. I’m hearing the sound of Lagos.”

And I remember, this was so funny, the friends told him, “You know what? We think you’ve been working too hard. Don’t go to work today. Just take a taxi, come back home.”

But I think he was like, you know, I have to get to the bottom of this. He followed his ears to the direction where the sound was coming from, then walked into the reception and like, “Okay, you guys really have to tell me what is going on here because I know the sound is from Lagos. I grew up here, but what is the sound doing here?”

So that was a shift for me, that moment on that perception of sound. It’s a transportive experience. It transports you to these places.

My name is Emeka Ogboh. I’m a Nigerian artist living between Germany and Nigeria, and my work incorporates the five human senses.

Working on the idea of the Lagos soundscape or just listening to the city in general opened my ears up. I see the city as a composer. And what I mean by that is, the city decides what it puts out. I’m just documenting the city. And for every city it’s different.

I’ll give you an example. In Lagos, we do not have sound ordinances. So you’re gonna find people using their car horns indiscriminately, you’re going to find people throwing a party on the street. The churches and the mosques do not care if they wake you up by 4:00 a.m. or if they keep you up all night. So you will hear different layers of sound at any time of the day.

Contrast there to somewhere like Berlin, where your neighbors will probably call the police because you’re throwing a party. Or where you have the government monopoly on what sound you hear. This is typical of the Western world, where you are forced to listen to police sirens. But then you, yourself are not allowed to be part of that composition because of the sound ordinances in the city.

I used to do a lot of field recordings in Lagos, but when I moved to Berlin, I actually stopped recording because I felt there was nothing for me to record. Coming from the intensity of Lagos, it sort of made me now try to look for sounds. And that also opened my ears more to Berlin. What will I find out about the city and how do I find this out?

I do not take what I hear for granted. You know, I’m curious to listen to the city and you can tell so much about a place from the sound generated in this place. So, my approach to cities is what is called deep listening, paying more attention. Also, like, you do this willingly. It’s not like bumping into sound or passing through sound. This is active listening to hear stuff, to experience stuff. So I do that and it changed my life, not just my practice. It made me pay more attention.

So I’m creating compositions. Because there’s so many layers of sound.

Lagos State of Mind—this is a very special piece to me because I’ve been living between Berlin and Lagos and it sort of summarizes my expatriate experience living in Berlin. You know, shuttling between two places, your brain has to do this switch. And that fusion of two places started occurring to me.

I wanted to create a piece that had elements of two cities. But I didn’t want a situation where I separated the two completely to say, “This is Berlin and this is Lagos.” I was more interested in placing them together and finding the intersecting points. That is when I tapped into my deep listening.

I was looking for sounds that would place me in these two different places. So you’re going to hear the sound of automated voices calling out train stops in Berlin, the sound of Lagos bus stations, the sound of Lagos bus conductors.

I recorded a lot of the transportation modes because I figured out that this is where you can hear so many layers of sound and different languages.

In Berlin, the train stations, they are mostly automated voices, which is not what happens in Lagos. You know, Lagos is more like the bus conductors doing it in real time, and I decided that the best way will be to blend almost like a call and response situation, where the Berlin automated voice announces, the Lagos replies, or vice versa.

You’re also gonna hear sounds of hawkers selling their wares in Lagos, the sound of the expatriates learning German in Berlin. Because thinking about the whole process of my stay in Berlin, one of the things was languages: How do I kind of bring in the element of trying to learn a new language? So I recorded German class sessions where mostly expatriates from Africa were having German lessons.

Well at some point I had to throw in music into it. I started making music in Berlin. That was when I started having this whole connection with the electronic world. And for me, making music is still the fusion of two places. Electronic music inspired by Berlin and field recordings for Lagos, which is also the summary of this piece.

The musical piece you’re gonna hear in this work is called “Danfo Mellow.” And it’s basically that feeling of being in the Danfo bus, which is the main public transportation system in Lagos.

It’s a track about movement through Lagos, where the Danfo is sort of always in a rush, but it’s been forced to slow down because of this traffic and just go with the flow, so I added this musical part of the piece in 2020 after the album came out.

I’m known to be a sound artist, but these days I try to describe my work, like I work with the five human senses without locking it down on just one specific sense.

With sound, you are hearing stuff and there’s no visualization of what you’re hearing. So that offers you the opportunity to create your own visual. So it offers more to people without imposing and forcing a visual idea on their head. It sort of gives them that room to escape. It gives them that room to jump into their imagination and create whatever they want to create. Then they become part of that work.

When we say we miss a place, it’s not about what you see. It’s mostly about what you hear and what you smell. Because the truth is our hearing sense is actually more developed than our visual senses. We started hearing after the first trimester. So you actually started hearing before you started seeing in the womb. And those senses are far more developed.

There’s this whole exercise called listening to your environment. That is really the, the basics, or the core points, of soundscapes.

A soundscape can simply be defined as the acoustic environment as perceived by human beings. And this can be natural or artificial. The acoustic environment is split into three subsets: biophony, which is the sound you’re gonna hear from nature, like animals, barking dogs, birds. And geophony, which is the sound of weather elements and nature, like rain, thunders, and stuff. And then antropophony, which is the sound humans generate in the environment, like vehicles, traffic. This is the simple definition of a soundscape, the acoustic environment as perceived by human ears.

So every year, there is World Listening Day, where people pay attention to the environment. This is how we stay more connected to our environment. This is how we understand our environment. Like I said earlier, you can tell about a place through the sounds that place is generating. You [can] also tell about the climate changes going on around the world. Maybe, at some point, the birds they migrate earlier, so you don’t hear them anymore, or you’re still hearing them in the winter, for whatever reason. It tells you something is wrong somewhere, the climate is changing. I think it’s a very important exercise for all of us to spend time listening to our environment.

We always try to build this bubble around us. I also do that. I also wanna listen to music or some podcasts at some point, but sometimes I force myself not to head out of my house with my headphones because I would definitely use it. I think we should unplug their headphones more, pay more attention to our space and know what’s going on.

It changes you as a person. It makes you pay more attention. We spend our time, our energy, really letting the visual guide us. But I think we should all develop our senses of hearing further.

Born in Nigeria and based between Lagos and Berlin, Emeka Ogboh creates multisensory work that takes the form of audio, installation, sculpture, and even beer. Since 2008, Ogboh has used the technique of field recording to capture and represent the experience of place and evoke rich personal and collective memories. In addition to creating sound installations like Lagos State of Mind II, Ogboh also creates music that blend electronic beats with the ambient sound of field recordings.

This episode was produced and edited by Arlette Hernandez with mixing and sound design by Marc-Auguste Desert II and music by Emeka Ogboh. Music tracks include (in order) “Palm Grove,” “Wole,” “Danfo Mellow,” and “Lekki Aiah Freeway.”

MoMA Audio is supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Related articles

-

Magazine Podcast

Ten Minutes with Monét X Change: On Drag

The winner of RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars reflects on how drag changes us for the better.

Monét X Change

Jun 21, 2023

-

Magazine Podcast

Ten Minutes with Adam F. Bradley: On Invisible Man

It’s been 70 years since the publication of Ralph Ellison’s iconic novel. Hear how it continues to resonate today from a writer who studies the author’s most private documents.

Adam F. Bradley

Jun 24, 2022