Looking for the Sonic Boom: Designing Sound for The Tuba Thieves

The director and two of the sound designers on the film, screening as part of Doc Fortnight 2023, talk about the politics of listening.

An unusual spate of crimes took place in the Los Angeles area in the early 2010s: tubas went missing from one local high school, then two—and ultimately 12 in all. These events form the basis of the new film The Tuba Thieves (2023), which screens February 25 in its New York premiere as part of our 2023 Doc Fortnight festival. But, as its director, Alison O’Daniel, puts it, her film isn’t about missing tubas or thieves. Instead, The Tuba Thieves reflects on the politics of sound and asks what it means to listen.

The genre-defying work interweaves multiple storylines, one involving a Deaf drummer playing a fictionalized version of herself, another following one school community in the aftermath of the theft, and others besides, all densely collaged together. O’Daniel, who is a Deaf artist and filmmaker based in Los Angeles, invited three composers—Christine Sun Kim, Steve Roden, and Ethan Frederick Greene—to create scores that would inform the structure of the screenplay. In a wholly experimental way, the film tells a story through sound and its absence. Below, O’Daniel shares her process and the approach she and her collaborators took toward sound design in a film where sound itself is the main character.

—Sophie Cavoulacos, Curator, Department of Film

The Tuba Thieves. 2023

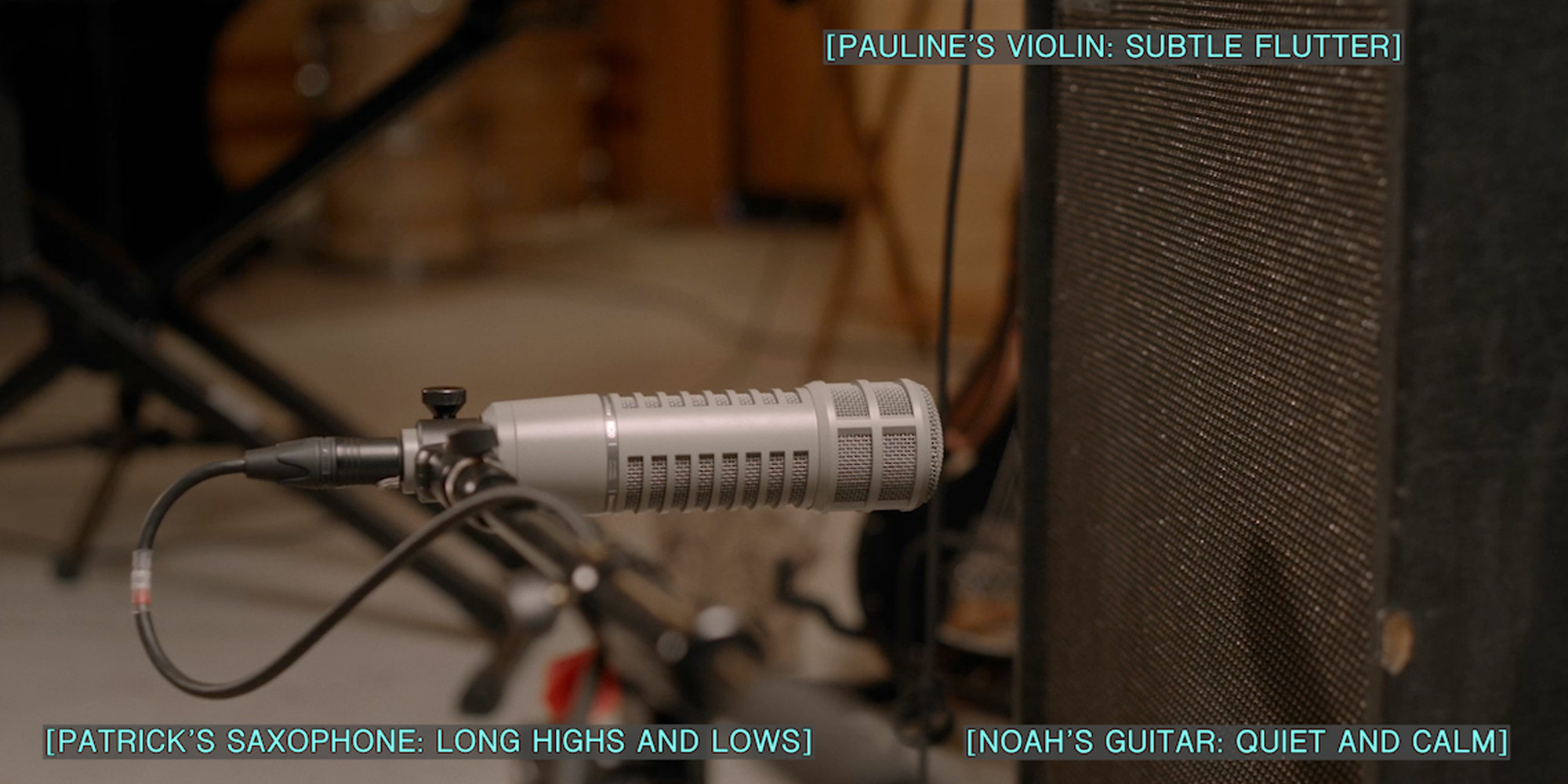

Arturo Salazar (“Frosty”): Almost nobody, not even the people inside of cinema, understands how sound design actually works. They don’t understand that we redo every single sound. It’s not natural. We have to make people feel that it’s natural. I don’t think it’s lack of interest, because everyone that I’ve taken to a foley session is amazed. It breaks their head understanding that you actually have to create the sound and mold it, all the time thinking in layers. In this movie, I felt like all the sounds were really personal. So it’s not just about how the sonic boom sounds. It’s about how this sonic boom in this movie sounds.

We tend to think our job is to create, to mimic reality. And that’s false. I think our job is to mimic subjective perception because you won’t be able to hear all the footsteps of everyone all the time. You won’t be able to hear the clothes. But our ears can focus attention on different things. We have to use our tools to create what the brain is doing. We have to mimic that focus, and then you’ll have this experience of being in the head of this person, of being in that room.

The Tuba Thieves. 2023

Alison O’Daniel: As I think back to the sound team working together, I think my favorite aspect was this kind of extreme focus and then also pulling out. Talk about sound layers! The whole time I was filming I was talking about visual layers to replicate my hearing. I wanted this feeling that there’s stuff getting in the way. I want the audience to feel like they have to look around something in order to get the full picture. So I would literally film behind a post or a fence, to make you feel a little bit of frustration. Visual layers could be in direct relation or opposition to sound. Frequently, I ask cinematographers to try to film with their ears, and I remember Meena Singh (The Tuba Thieves’ first DP) had this expression on her face that I interpreted as perplexed excitement: What does that even mean?

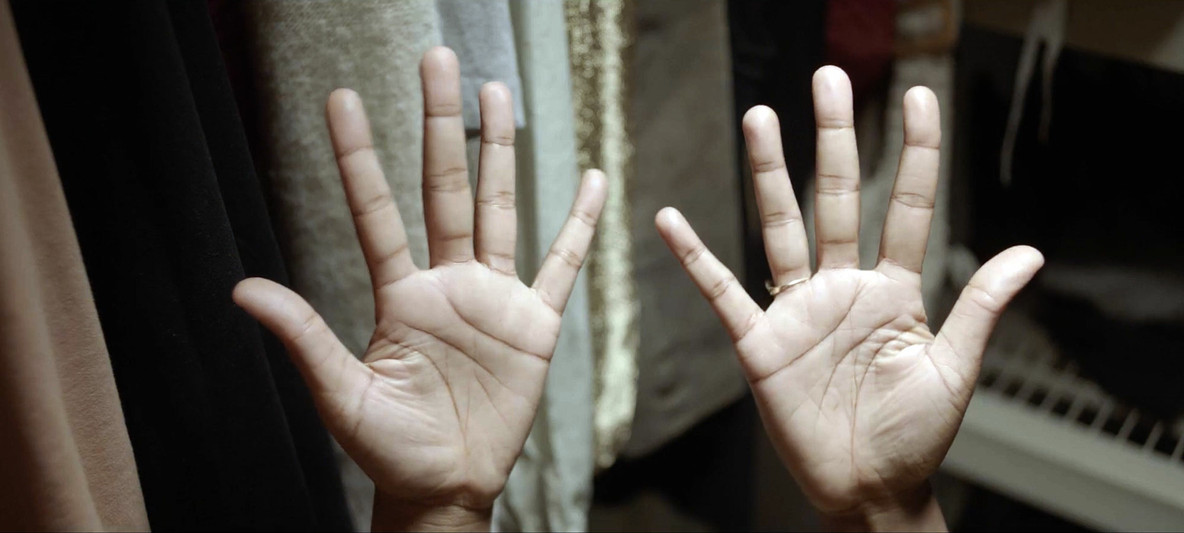

And yet I didn’t want to ask you to think through visual language, because I think that’s what sound artists are always forced to do. They’re always in service to the image. I started this project with composers creating the soundtrack before there was narrative, and now ending it with you all, there’s something about the way that you and [sound designers] Chema [Ramos Roa] and Sofia [Hernández Ortega] really focused on the sound of skin touching…I love that so much. I’ve always written into scripts clothing rustling, but skin touching! That’s a sound I can’t hear. Even doing that [rubbing hand across arm] right next to my ear. I can’t hear it. And so the fact that the sound of skin touching was valuable to you all, it blew my mind because it was so micro-focused, building all the sonic layers.

Sign Language can be very noisy; the sound of someone’s hand touching their chest or their clothes, lips moving, clicking, smacking, small guttural sounds, wind through a gesture, etc. But when it’s actually soft touch of skin on skin, I find that perplexing and amazing. And it was really one of those moments where I was like, I’m giving over to your expertise. To let go as the director, and as someone who’s Deaf, to let go and let you be the ears of the film, it’s amazing when this is a good experience. It hasn’t always been for me.

The Tuba Thieves. 2023

María Alejandra Rojas (“Maja”): And for us, it was completely different from all the movies that we have worked on, because those kinds of (Deaf) sounds in most films are just noise. We have to take out those sounds usually. We think those are the ones that people don’t want, because nobody’s actually paying attention to those details in real life. Even if we recreate all those sounds in other movies, at the end it’s in the mix, but they’re always taken out: “We don’t need that.” But it’s included in The Tuba Thieves. We had to keep moving and not get lost, because it was so different.

AO: What do you mean when you say lost? You mean lost to too many details?

AS: Like, what is the thing that we want to make the audience feel? What’s the purpose of this? It was definitely not a movie where you see a dog and you need to hear a dog. And when you open all those possibilities, losing track of the right path might be easy.

MAR: Then again, I think that’s what we saw the first time we watched it. This is not our way of understanding life, and this is not our way of understanding sound, and this is not our way of understanding a film—but the conceptual decisions, most of them were there.

AS: Understanding that we are people that hear, and not only people that hear, we need to leave many of those decisions to you because we don’t know shit about not hearing. It’s just something we haven’t experienced. It’s a feeling that you hear. It translates to a sensation. It’s finding that third meaning. I remember that we discussed the sonic boom a lot, and we were just looking through all the possible libraries of sonic booms and different layers.

MAR: And then, I remember you said, “No, we don’t need that. What if we just keep going with the skin?”

AS: And I was like, “Skin is the sonic boom? Oh, my God!” The lightest of sound, with the loudest of sound, and then everything at that moment kind of clicked: where everything was going, and the feelings, and when Alison was saying all the time, “I need more of the scenes to be really physical.”

AO: Yeah.

MAR: And I remember the word you used: “haptic”—and we didn’t know that word in English—we were so thankful, because those directions were never given to us. You were saying in one of your interviews, “Don’t soundsplain to me, but when I ask you to, then do it.” That’s why the captions were so helpful!

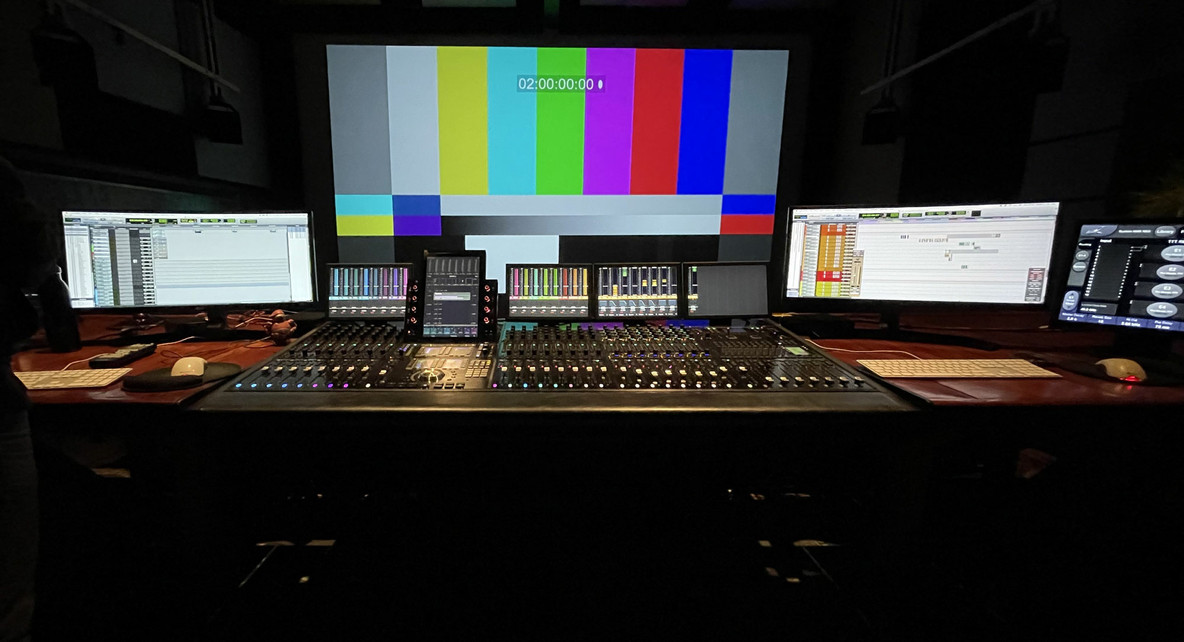

The sound board at Splendor Omnia postproduction studios

AO: We had so little time. We had to just dive in and really get to know one another. But those spotting sessions where you’re really trying to put to words experiences that go beyond language, and yet we’re sitting there having conversations about the minutiae of the sound design. It makes me think about how you said that so many films take out those sounds. From a Deaf perspective, I don’t even understand how you can consider cleaning up sound. I always read these things where people talk about a film as “slick”; they used that word a lot. So that’s what it makes me think of when you’re saying that people would remove sound. But then it would be too slippery. At Sundance [Film Festival], people cheered when the sound design credit came on, so obviously us not removing things was the right thing to do.

AS: There’s no movie with four or five sound designers. That doesn’t exist. It’s really weird. But I remember when I proposed it, I knew that was what this movie needed. From the beginning, we knew that you were our sound designer. We weren’t just the head that has all these ideas and answers, and you were not just our director, but our sound designer. We felt that trust from the beginning. For us, you were drawing the map, and it was really philosophical, too, because we were trying to describe things that, even for us, don’t exist.

AO: Yeah. And at Splendor Omnia, there were all these other sensory stimuli that really supported the process: running down a path and stumbling across a lonely horse, and later putting two and two together and smelling the other horse decomposing near the sound studio. It sounds horrifying, but it was just part of it. And the smells or, like, having Dica, the Chihuahua, sitting in my lap during a sound session, or sharing the most amazing meal. I think we never would have been able to pull off that level in that amount of time if we weren’t feeling all of that in our bodies. We were so engaged.

A lonely horse near Splendor Omnia

MAR: For me, it was the human touch that was really important, that we usually never have in this industry. It’s really cold most of the time. So I think that warmness that you’re talking about in that closeness, and also being in nature—we actually reached a point that made us make really good decisions. And then, if we were lost, we could leave, go outside or walk down a path, and then go back in.

AO: We have an intern working on the film right now who is hard of hearing, and kind of new to her Deaf identity. She told me when she watched the audiology scene that she cried. I asked her, “Have you cried in audiology appointments before?” She has. So have I. Audiology and accessibility can be so violent. The intention of these things is to help, but there’s this thing about that experience where you’re in that booth, and they’re testing you and putting these tones into your ears, but it feels extractive. It feels like something is being taken, and it feels like you’re not doing it right. And it feels so bad. So I loved that you responded to that and then transformed it.

When I started this project, I was trying to figure out what it means to make a listening project. And I think, in the end, where I landed is that throughout the whole project, there was a really deep reverence and respect for listening. You trusted my ears, and trusted my relationship to my ears. You were never posturing that you know more than me, even though you totally do. It’s hard for me to overstate how profound that is, for me to feel listened to.

Doc Fortnight 2023, the 22nd edition of MoMA’s Festival of International Nonfiction Film and Media, runs February 22–March 7, 2023, and is organized by Sophie Cavoulacos, Associate Curator, Department of Film, and Julian Ross, Leiden University Centre for the Arts in Society, with Chandra Knotts, Filmmaker Liaison, Department of Film.

Related articles

-

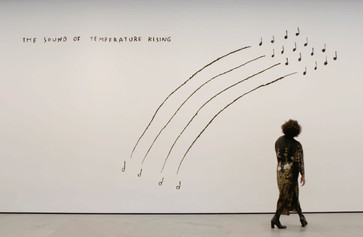

UNIQLO ArtSpeaks

Lanka Tattersall on Christine Sun Kim’s The Sound of Temperature Rising

A deceptively simple drawing combines text, music, and American Sign Language to “set your mind on fire.”

Apr 15, 2022

-

A Look at the Landscape of Our Time from a Hundred Feet Underground

Read an interview with artist Jenny Perlin, whose Bunker launches this year’s Doc Fortnight film festival.

Jenny Perlin, Sophie Cavoulacos

Feb 18, 2022