Ming Smith and the Energy of Jazz

The artist takes us on a journey through jazz and blues that inspired the photographs in her exhibition.

Ming Smith, Habiba Hopson, Kaitlin Booher

Feb 1, 2023

“One summer night, I had the windows open and I could hear a neighbor playing Miles Davis’s Sketches of Spain,” the photographer Ming Smith recalled. “There was a crack in the record because they had played it so many times. It was really romantic and I just thought, ‘Wow, this is Harlem.’ I wanted to somehow take that [moment] and put it in my work.”1

When Smith arrived in Harlem in 1972, her new community became a refuge and a source for creative inspiration. Camera in hand, she encountered the neighborhood’s effervescent street life, cultural ferment, and musical heritage. Created in conjunction with the exhibition Projects: Ming Smith, the songs on Smith’s playlist conjure the artist’s personal memories, as well the history of jazz and the blues. Some, such as Pharaoh Sanders’s The Creator Has a Master Plan and tracks from John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, reference Smith’s undergraduate years at Howard University. Others, like songs from Alice Coltrane’s album Reflection on Creation and Space, serve as tools for introspection, a key to Smith’s artistic process.

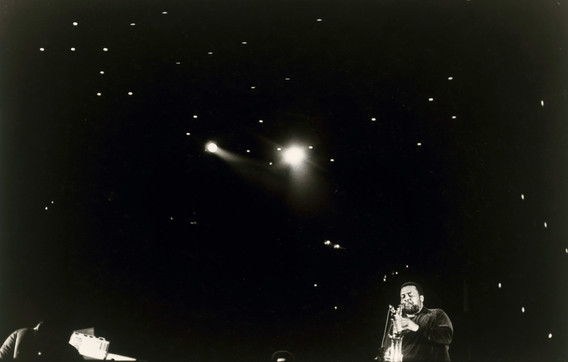

Ming Smith. Arthur Blythe in Orbit, Berlin, West Germany. 1981

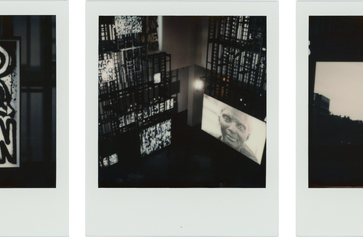

Ming Smith. Sun Ra Space II, New York. 1978

Musical metaphors figure frequently in Smith’s aspirations for her photographs. As she put it, “If people could feel what I feel when I hear a Billie Holiday song—that’s what I would want them to feel when they look at my work.”2 Using slow shutter speeds and low lighting, Smith established a photographic style that favored blurred imagery. She later compared the freedom she felt experimenting with her camera to the improvisational riffs of jazz musicians. For the late critic and musician Greg Tate, Smith’s photographs of celebrated Black jazz and blues musicians capture something ineffable about musical experience: “Part of the rhetoric around free jazz is that it’s cosmic energy music, music concerned with invoking and evoking spirit possession… we definitely see a connection between that idea of energy music and Ming’s work that has the blur, has a similar kind of vibratory harmonics going on.”3

Throughout Smith’s playlist, sound registers across the senses—from the rich vibrato of vocalists Betty Carter, Ella Fitzgerald, and Sarah Vaughan to the cosmic and harmonic arrangements of Sun Ra and his Arkestra. This invisible domain of the sonic is an essential accompaniment to Projects: Ming Smith.

Projects: Ming Smith, organized by Thelma Golden, Director and Chief Curator, The Studio Museum in Harlem, and Oluremi C. Onabanjo, Associate Curator, Department of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art, is on view at MoMA February 4–May 29, 2023.

-

Ming Smith in conversation with Oluremi C. Onabanjo, Kaitlin Booher, and Habiba Hopson, September 16, 2022

-

“A Portrait of the Artist: Ming Smith in Conversation with Janet Hill Talbert,” in Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph, ed. Brendan Embser (New York: Aperture Foundation, 2020), 17.

-

“The Sound She Saw: Arthur Jafa in Conversation with Greg Tate,” in Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph, ed. Brendan Embser (New York: Aperture Foundation, 2020), 220.

Related articles

-

Playlist

Who Will Survive America: A Playlist Inspired by Who Is Queen?

Explore song selections from Jacques Morel that evoke the “radical juxtapositions” of Black Dada.

Jacques Morel

Oct 27, 2021

-

Free Design: Jazz Posters That Swing

In celebration of International Jazz Day, we present a selection of jazz concert posters from MoMA’s collection.

Jason Persse

Apr 30, 2021