Femme Camp

Camp belongs to women, too.

Leah Dickerman

Jun 10, 2019

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute celebrates camp in its most recent show. With early sections painted a dusty pink and filled with sound—Judy Garland singing “Somewhere over the Rainbow” and recitations from Oscar Wilde’s plays—and fashion at its wittiest and most extravagant, Camp: Notes on Fashion culminates in a gallery of costumed mannequins in double-height storefront-style displays. The total effect is at once brilliant and beautiful. But if camp has never seemed more relevant, it also seems unduly constrained here. Camp's protagonists are presented in a way that is very white (as some coverage of the show has noted), and very male. The show only hints at the use of camp by women—a flamingo hat by Elsa Schiaparelli and Garland’s voice stand out. To the degree that great curatorial work is about creating conversation, I wanted to throw in two cents—or two sequins.

In 1964, a young Susan Sontag took on camp as a serious subject, one worthy of sustained cultural commentary. Her mediations on the subject still shape our thinking today. This is true of the Met show: curator Andrew Bolton says the show was inspired by her essay; there is a section dedicated to “Sontagian camp,” and the vitrines in the final gallery are organized by the manifestations of camp that she inventories. For Sontag, camp is a “sensibility”; in contrast with a style, it has many different looks. It is an “aesthetic view of the world” defined by “extravagance.” It’s something that can be found (Mannerist portraits by Pontormo, the court of Louis XIV or Warhol’s choice of Marilyn Monroe) or deliberately performed (Wilde’s dandy or Lady Bunny). The target of camp in Sontag’s understanding is all about the high/low cultural divide: it is aimed at taste, and especially at those who would dictate it. “The experiences of Camp,” she writes, “are based on the great discovery that the sensibility of high culture has no monopoly upon refinement. Camp asserts that good taste is not simply good taste; that here exists, indeed, a good taste of bad taste.”

Perhaps it’s easier to see at the distance of more than 50 years what’s subdued in this definition of camp: sex and politics. There are hints of it to be sure. Sontag speaks of camp’s recognition that sexual attractiveness, and perhaps sexual pleasure itself, “consists in going against the grain of one’s sex,” but at the same time also asserts that camp is “disengaged, depoliticized—or at least apolitical.” The fact that she does not place a politics of sex at the very center of her understanding may be why she struggles to define the particular affinity between queer male culture and camp: “Homosexuals have pinned their integration into society on promoting the aesthetic sense,” she writes in the language of the day. “Camp is a solvent of morality. It neutralizes moral indignation, sponsors playful.”

One might even say camp is a virtuoso form of play, a pressing on and releasing of the gas pedal with finely nuanced control.

Yet we can sense that camp is far more than an affront to taste. It is a kind of attention to the ways sex and gender are coded in culture. One might even say it’s a virtuoso form of play, a pressing on and releasing of the gas pedal with finely nuanced control. And camp’s knowing display, the performance that one is in control, is power; it’s a dart aimed at any understanding of these markers of gender and sex as natural, rather than just a boa to be flung around one’s shoulders.

That’s why, despite its proximity to gay male culture and drag, camp also belongs to women. Sontag notes Mae West and Greta Garbo. And we can make a list of many others: Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Vivienne Westwood, Bette Midler, Cindy Sherman, Lady Gaga…please feel free to add. My teenager named Janelle Monae. We debated that for a bit, but I think he may be right. On the other hand, the Kardashians are not camp, at least not the deliberate kind—the signs of sexuality are just inflated rather than performed with irony.

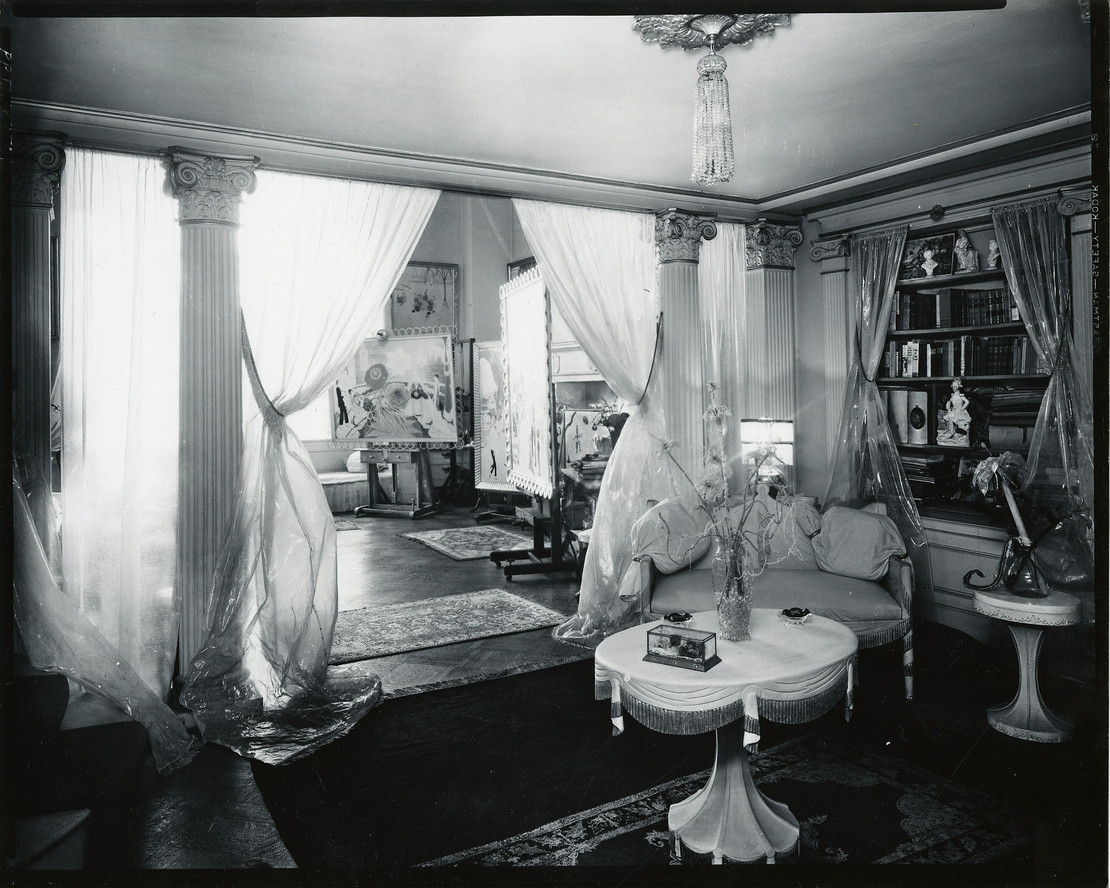

Peter A. Juley & Son. Florine Stettheimer's apartment, with a view of Family Portrait II on the far left. c. 1930s

What happens when women use camp? And what does this tell us about camp?

Let’s think of Florine Stettheimer, as I did in walking through the galleries. Her work has often been seen in terms of too much muchness. A poor reception to the only solo exhibition in her lifetime in 1916—one critic compared it to the “way an orchestra sounds when all the instruments are playing independently”—led her to debut her works at home, giving each a “birthday party” among friends, who included artists, critics, and tastemakers such as Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Henri-Pierre Roche, Henry McBride, Carl Van Vechten, Alfred Stieglitz, Cecil Beaton, and Baron de Meyer. This half private/half public setting was her stage and often her subject.

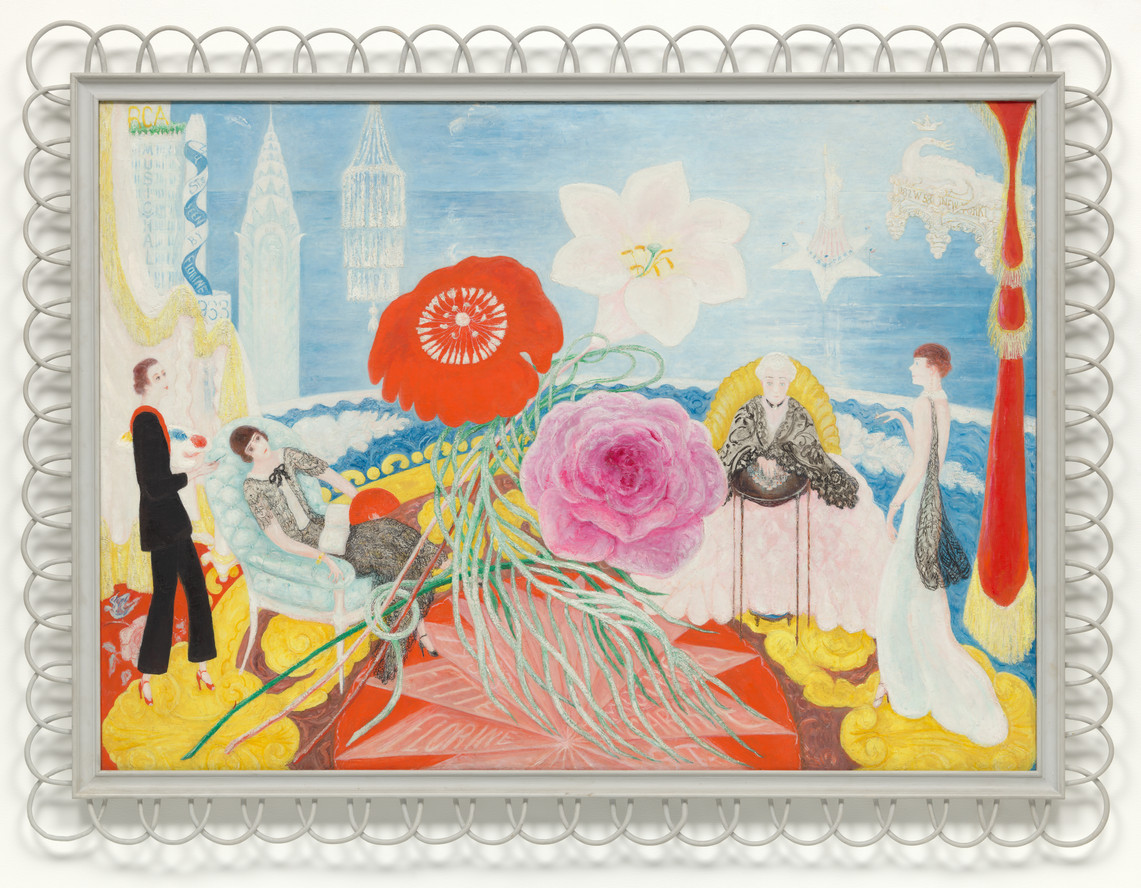

Florine Stettheimer. Family Portrait, II. 1933

You can see this in Family Portrait II (1933), a work we are lucky enough to have in our collection. Stettheimer called it “my masterpiece.” MoMA Director Alfred H. Barr Jr. wrote to the patron, collector, and gallerist Peggy Guggenheim that it was the one that he “badly want[ed]” for the Museum. Here, in this painting too, one can see how Stettheimer works in the register of camp.

At the very center of the painting, where one might expect to see the family, floats a bouquet of three gargantuan blooms in white, pink, and red. At right and left are four female figures: the artist, her two sisters Carrie and Ettie, and her mother. Her mother sits behind a mahjong table, fondling the tiles; Ettie sinks into an upholstered chair with an open book. The drawing room set-up takes on a stage-like formation with curtains draped at the sides: gold cellophane with gold fringe at left, red velvet with gold fringe at right. There’s also a chandelier out there somewhere. But instead of an audience, there is New York: the top of the newly completed RCA building at Rockefeller Center, the Art Deco crown of the Chrysler Building, Cleopatra’s Needle from Central Park, and Lady Liberty herself.

The distinctive line Stettheimer uses to depict her figures—stylized and serpentine—is telling. It speaks the language of graphic and fashion illustration, of decoration and ornamentation. Stettheimer’s facility with this idiom was well earned. In her European travels, she was tutored in the sensuous curves of art nouveau caricature by the English critic Max Beerbohm (Oscar Wilde, whose posturing effeminacy shocked Americans when he toured this country in 1882, was among his subjects), acquainted with the Viennese fin-de-siècle master of ornamental portraiture Gustav Klimt, visited the symbolist painter Gustave Moreau’s otherworldly house museum, and saw the Ballet Russes with Sergei Diaghilev. There’s a knowing mix of registers in Stettheimer’s paintings, of minor (or better, marginalized) genres and of ambitious painting.

All the surfaces are covered: with images, but also with paint, applied and built up in a way that seems thicker than strictly necessary. “Very early she began to lean heavily upon the use of white pigment,” wrote her friend the critic Henry McBride in a catalogue produced by the Museum in 1946, “...whites which were often piled up in relief before the actual painting began.” Adornments receive additional tactile attentions. Decorative edges and fringes are created with three-dimensional dots and strings of paint. There’s a bit of horror vacuii within this work of the type that can also be seen in images of the apartment Stettheimer lived in with her mother and sisters. Furniture is crowded together, chairs and table painted white with decorative gilded edges, and the gaps between pieces filled with painted screens. Her paintings and mirrors cover wall space, and billowing cellophane curtains drape the windows. “My attitude is one of love,” she writes in one of her poems, “Is all adoration/for all the fringes/all the color/ all tinsel creation....” (Her sister Ettie published Florine’s poetry after her death in a private edition called Crystal Flowers, intended for circulation among her friends.) In her family portrait, too, Stettheimer abandons the expected simplicity of modern frames. She uses light gray looping wicker curls to create a scalloped edge with an exaggerated decorative quality.

Art historian Linda Nochlin once spoke of the artist’s “preferred setting: New York, West Side, feminine, floral, familial.” Each of these terms—*feminine, floral, familial*—is coded pink. Can we see Stettheimer’s intensification of this trio as a knowing adjustment of the levers, pushing things hard in a kind of hyperbolic femininity?

Florine Stettheimer. Love Flight of a Pink Candy Heart. 1930

Another of Stettheimer’s paintings, a pastel-colored confection now at the Detroit Institute of Arts, is titled Love Flight of a Pink Candy Heart (1930). On the back stretcher is a poem, with lines that read, “In Memory of a Sugar Coated Heart/My House on Paradise/(My party) ← Arcadia/Beautiful Young men/I have known.” Ettie describes the image in a note penned at the time she gave the work to the DIC as an older Florine “contemplating various friends of her youth.” Here the artist’s slight figure looks down from her balcony on a picnic scene in which two young women dressed in evening clothes lie around the spread with three young men, one absorbed in reading his book, and two others sprawled with bronzed limbs barely clad in bathing suits. Of course, there is nothing campier than older woman acknowledging sexualized memories and desires. (This is the terrain that Mae West explored in presenting herself as a sex symbol with seeming disregard for age, all the while parodying the idea of a sex symbol—her performance proving the rule that female sexuality is only socially applauded when it is young and nubile.) And everything here suggests Stettheimer’s knowing play, from the title, which loads on the clichés of sentimental romance, the huge petals looming over the scene as wonderfully exaggerated symbols of sexuality, to the naked young man riding a white horse in the background as a kind of latter-day Sir Godiva. Perhaps most transgressive is the way she reverses expectations, so that we see her male figures through a rose-colored, feminine lens.

That’s the power of camp, isn’t it?

Sources:

Barbara J. Bloemnik, The Life and Art of Florine Stettheimer (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995)

Andrew Bolton, and Karen Van Godtsenhoven and Amanda Garfinkel, Camp: Notes on Fashion (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019). Includes Susan Sontag, "Notes on Camp", 1964.

Stephen Brown and Georgiana Uhlyarik, Florine Stettheimer: Painting Poetry (New York: The Jewish Museum; New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2017)

Linda Nochlin, “Florine Stettheimer Rococo Submersive,” Art in America, May 5, 2017, https://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/magazines/from-the-archives-florine-stettheimer-rococo-subversive/ (May 28, 2019)

The Meditations series presents personal reflections on art and culture from staff and members of the broader MoMA community. The opinions shared are those of the author, and are not intended as statements from The Museum of Modern Art.

Related articles

-

Come As You Are: A Space for LGBTQ Teens and Art

Teens share their thoughts on art and what it means to create safe, celebratory spaces for LGBTQ communities.

MoMA

May 31, 2019

-

New to MoMA

Remedios Varo’s The Juggler (The Magician)

How will this new addition to MoMA’s collection shake up conversation in the galleries?

Anne Umland, Cara Manes

Jan 18, 2019