A Contested Land: A Conversation with Carolina Caycedo and David de Rozas

The artists discuss West Texas, environmental justice, and their new Projects exhibition at MoMA.

Carolina Caycedo and David de Rozas. The Teachings of the Hands. 2020

When Carolina Caycedo and David de Rozas first visited West Texas, they were struck by the number of fences that prevented people from accessing the vast lands surrounding the highway on the long drive from El Paso to Marfa. Interested in what they call “brute force infrastructures”—large-scale projects such as dams and border walls built to exercise control over the natural environment and the bodies that inhabit it—they set out to investigate the history that shaped a territory where 95% of the land is privately owned. This investigation resulted in a series of multimedia works, commissioned by Ballroom Marfa, that make visible some of the cultural, scientific, industrial, and sociopolitical forces behind the urbanization and resource extraction in the region. The Teachings of the Hands (2020), a film created in collaboration with Juan Mancias, chairman of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas, is at the center of the artists’ new Projects exhibition at MoMA. Narrated by Mancias, it recounts West Texas’s complex history of environmental violence by weaving together archival footage, reenactments, and archaeological artifacts. Firmly rooted in a territory where Indigenous knowledge has seldom been recognized, the work also stands in solidarity with the Carrizo/Comecrudo’s struggles against ongoing forms of colonization.

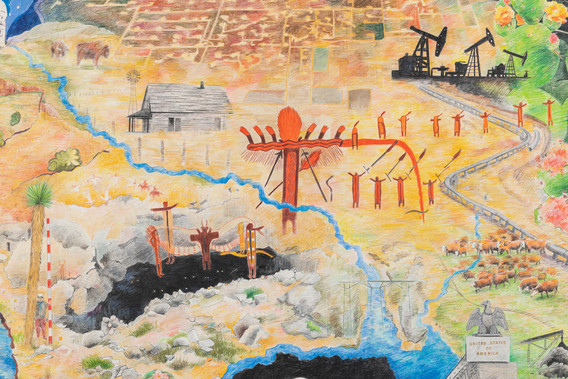

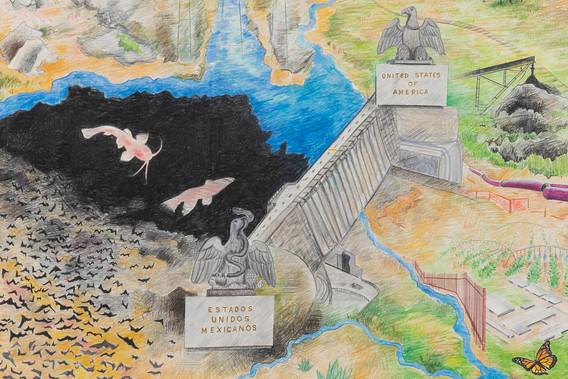

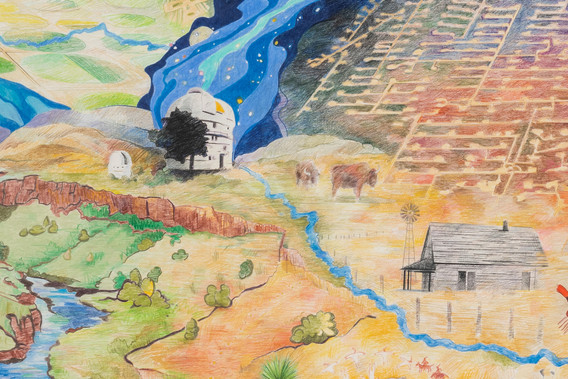

On the occasion of the opening of the exhibition at the museum, Caycedo and de Rozas invited Mancias to participate in a conversation. They were joined by C. J. Alvarez, an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin and author of Border Land, Border Water: A History of Construction on the U.S.-Mexico Divide. The discussion was structured around the main locations depicted in The Teachings of the Hands, as well as in Somi Se’k (The Land of the Sun—La tierra del Sol) (2020), a drawing that takes its name from the term used by the Carrizo/Comecrudo to refer to the lands on both sides of the Rio Grande (comprising the Chihuahuan Desert, the Rio Grande Valley, and the delta). Depicting key landmarks and some of the animal and plant species across the region, the drawing functions as a “counter-geography” that prompts us to understand the region as a “multilayered net of universes where the region’s present, past, and future are still in conversation.”1 Mancias, Alvarez, and the artists spoke about the ways the built environment has historically affected the ecologies of West Texas, how digging into the past can inspire movements that are fighting for environmental justice today, and the ways in which we can reframe our connection to the land by altering our understanding of time.

—Anna Burckhardt, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Architecture and Design

Carolina Caycedo and David de Rozas: We would like to begin by discussing the three locations that occur in Somi Se’k and also in our research for The Teachings of the Hands. I’m talking about the Amistad Dam on the Rio Grande, the Permian Basin, and the McDonald Observatory, close to Fort Davis. So, Juan, can you give some impressions about them?

Juan Mancias: We often talk about the trails or the pathways, and the journey of our ancestors along these areas. And in viewing this drawing that Carolina and David put together, it can give you an understanding of the presence of the original people of Texas. The assumptions that are made by historians and other archaeologists need to be challenged. And that’s exactly what I have been doing with the stories that my grandfather would tell me.

As a matter of fact, right now I’m putting a map together, indicating where all of these villages were up and down the river, according to some of the historical facts that are out there. We’ve found that every eight to 10 miles, there was a village along the Rio Grande. But we have to understand that these villages were temporary. And so, we have to look at the temporal, because of the climate, and because of when the seasons would change. And that’s why the idea of the teaching of the hands is so important, because it is a calendar using the 28 sections of your fingers. You can put your hand up and you can count the sections. And then in between each one of them, and on each hand, you have the seasons and the important quarter markers of the seasons.

So our ancestors would move according to that. When the hurricane season came in, they would move inland to go hunt, and then they would come back. They would travel for about a week or two to hunt, and then they’d come back to fish, and then when they saw another storm coming, they would go inland again. Historians think that we didn’t know how to survive, but we’ve been surviving here for thousands of years.

The part of the drawing that you see here with the monster with the big head, which references a particular pictograph in the region, that’s flaring––that is the fracking up in the Permian Basin, and then you see the caverns that are in Sonora. And now politicians are asking for an expansion of fossil fuels to accommodate what’s going on in Ukraine and in other countries.2 So it’s not any different than what happened 500 years ago, when colonizers came and got the gold, the silver, and other resources, and took them across the ocean, and were robbing the cultures here and taking away not just the resources but also their lifeways, and handing them religion.

Carolina Caycedo and David de Rozas. Detail from Somi Se’k (The Land of the Sun – La Tierra del Sol). 2020

Carolina Caycedo and David de Rozas. The Teachings of the Hands. 2020

Carolina Caycedo and David de Rozas. Detail from Somi Se’k (The Land of the Sun – La Tierra del Sol). 2020

CC and DDR: C. J., can you comment from a different perspective, perhaps drawing on the research for your book, Border Land, Border Water?

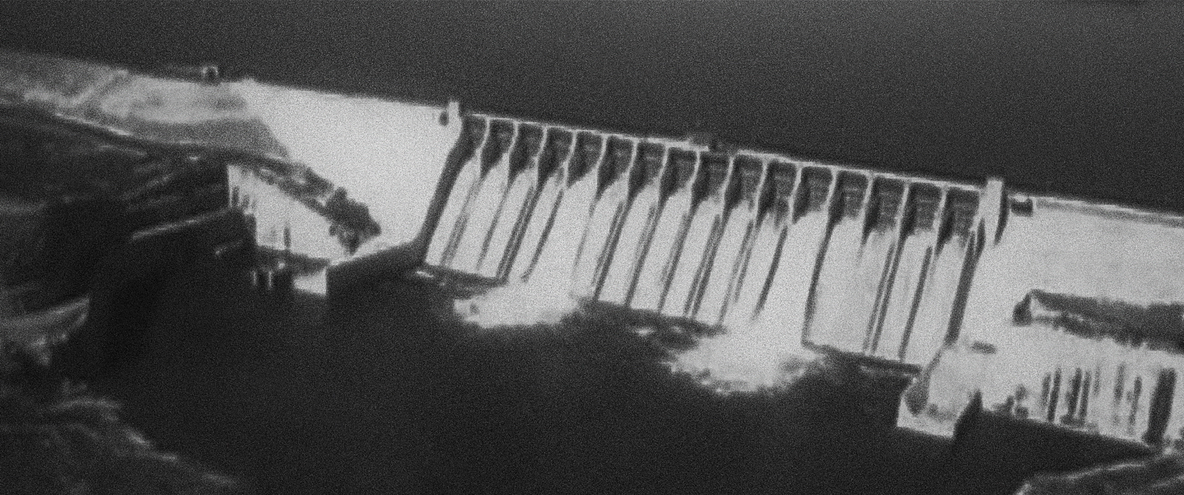

C. J. Alvarez: Part of what makes Amistad Dam interesting to me is that it is several things at the same time. It is simultaneously a cultural site, like Juan has explained, and it has this catastrophic dimension to it because of the ecological ramifications of flooding, and the implications that has for the rock art in the canyons.

At the same time, the dam has also delivered many people downstream from floods that they experienced before the dam went into place. It is also a very unusual example of collaboration between the United States and Mexican governments. We think about the border as this place of tension and confrontation between the two governments, and in many cases it is. But in the case of this dam, much less so. Half of it is in Mexico, half in the United States, built by both Mexican and American workers and engineers. So I think that it’s a very ambiguous space. It provides this benefit for people living downstream, but at the same time it also creates the circumstances for destruction.

It’s interesting to think about the observatory and the Permian Basin together, because the Permian Basin emits light through the flares that Juan was just talking about, and also through the artificial lighting that they use at night to illuminate the platforms for the derricks and pumpjacks. This is the exact opposite of the observatory, which is supposed to be dark at all times. So there’s this tension there, between the light emitted from the basin and the requirement for darkness that the observatory has. And the observatory, in collaboration with towns and businesses and government institutions and private landowners in the Big Bend area, has succeeded in keeping the skies very dark in this part of West Texas. To me, it’s such an interesting tension: the observatory is, literally, a dark sky preserve—in some ways the most ancient state of things, which is just darkness at night, with illumination solely by heavenly bodies. And the Permian Basin is doing the exact opposite: trying to take something ancient and convert it into something utilitarian and modern as fast as possible.

CC and DDR: Juan, I know together with the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe, you’ve been working to protect and defend the Garcia Pastures, a sacred site in the Rio Grande Valley that contains the remains of ancestors and cultural artifacts from various tribes, including your own. Can you describe the place, its importance, and the threats it’s facing?

JM: Garcia Pastures is right next to Port Isabel, on the Gulf Coast, and a few miles away from the mouth of the Rio Grande. Right now, a lot of the activists’ focus is there, but in the past nobody would listen to us about it. So when the gas companies started promoting the first five liquified natural gas (LNG) terminals back in 2016, three of them were right there around Port Isabel, where the ship channel is located.3 We’ve found that there was a national registered historical marker there and have worked with the archaeologist who did the study for the US Army Corps of Engineers. We approached them about letting us present offerings to the ancestors whose remains are buried there.

Many of our people still go up in that area and fish, following a tradition that’s been there forever, because these are fishing villages to us. That area is called the Loma Ecological Reserve, and the kind of beach sand hills that you find there are only found in three places in the world. And that’s why we’re fighting these LNG terminals very hard, because that whole area was used for ceremonial use, or for our habitation. And some of our birth rituals come from that area, because to us that’s where the first woman was born, at the mouth of the Rio Grande.

So, this area still maintains that sacredness to us. And of course, now that SpaceX is building right up next to Boca Chica, they closed the only public access road to the beach, and they tell you that you can’t get to the beach because Mr. Musk is testing engines.

Carolina Caycedo and David de Rozas. Detail from Somi Se’k (The Land of the Sun – La Tierra del Sol). 2020

Carolina Caycedo and David de Rozas. The Teachings of the Hands. 2020

CC and DDR: Could you both comment about the overlap of infrastructure and environmental damage, and also if there have been other moments of resistance along this territory? The Garcia Pastures has been a starting point to speak about digging into the past, digging into history and identity building, and how holding onto ancestral teachings can fuel the environmental struggle.

JM: A settler mentality, or a colonizer mentality, is what prompts people to see a dead bear and call it a Mexican bear, which happened recently on the I-10 highway. And I’m going, like, did you check its papers? How do you know it’s Mexican? That bear doesn’t know that it’s Mexican, you know? We’re throwing nationalities out there like that’s the most important part of what’s going on. CJ, you were talking about the Amistad Dam being built by Mexicans and by Americans, but they’re human beings. They’re trying to find a way to survive for a larger population. But we’re tagging everybody, instead of trying to live in a sense of understanding that this is the only place we have to live right now.

Now billionaires are trying to invade other planets and take the resources there. Eventually they’re going to exploit the land there, like humans have been doing on Earth for centuries: we’re killing the environment, exporting resources from this land, across the oceans. And I think that we have to be able to recognize why it’s important to look at this historical presence from a perspective of the original people of the land. Otherwise, we’re repeating history over and over again. They still look at us native people like you’re only here to be seen and not heard, and we have to be able to stand up for our rights, and for the inherent rights of the land.

Carolina Caycedo and David de Rozas. The Teachings of the Hands. 2020

Installation view of Projects: Carolina Caycedo and David de Rozas

CA: I think that, for a lot of people living in Texas, it’s a real challenge to think expansively about time. I think that it’s very easy to fall into the trap of thinking that history starts when the state of Texas came into being. And I think about what you were saying, Juan, that the existence of the United States and Mexico is another impediment to understanding deeper time, because it’s easy to fall into these national narratives. But from an ecological point of view, thinking about time immemorial as a way of understanding the landscape and the people who lived there is just a different way of measuring time in the desert. It’s a landscape that is simultaneously very hardy—like each individual plant is hardy because it’s been adapted to a stressful environment—but at the same time very fragile. And it’s a landscape that takes a long time to heal when you manipulate it with things like cattle grazing and dam building.

I think that the more we can think about the passage of time in ways that do not reinforce nationalist narratives and that are not driven by the history of infrastructure, the more we will be able to have sophisticated conversations. Which means thinking about the way that non-human entities experience time, the very slow growth of many desert plants, the ancient history of the Rio Grande and its tributaries. And, like Juan was saying, the long-term occupation of people way before there were such things as the United States, or Mexico, or Spain, or any of the political configurations that we often default to as a way of organizing territory and identity.

JM: It is also a matter of recognizing assumptions that can lead to the romanticizing of cultures of this land, especially because of what white settlers have done to us as a people, and what they keep doing. The state of Texas still keeps us out of sight, out of mind. We were fighting one of the disposal wells (depleted oil wells used to dispose of waste fluids like brines) up in Pecos County, and we held them off for almost two, three months, until the person in charge of handling the claims decided that we didn’t have enough qualified and certified experts to do what we were trying to do. She even questioned who I am and was saying that she needed more information, even though she could write a book from the stuff that we handed her.

We were concerned about them naming the disposal well after one of the Comanche chiefs; they were going to call it Chief Big Hump. I’m going, “My gosh, why are they doing this?” I mean, that’s totally racist. That’s going against everything that we are. If you read about Chief Big Hump, he didn’t want anything to do with a disposal well.

And then I started realizing that they did the same thing with the Yellowtail Dam up in Montana. Robert Yellowtail, chairman of the Crow Tribe, was totally against the dam, and they still named it after him.4 It’s one of those things that seem like a slap in the face. They are saying: we’re going to need the water, we need this, we need that...and just forget y’all. Forget about your lands, forget about your burial grounds.

Projects: Carolina Caycedo and David de Rozas is on view at MoMA through January 2.

-

Carolina Caycedo and David de Rozas. Text for the exhibition label at the Visual Arts Center at the University of Texas at Austin, shared with the author, 2021.

-

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in the spring of 2022, the European Union proposed banning Russian oil imports, choosing instead to focus on oil produced in the United States. In March of 2022, President Joseph R. Biden promised to deliver at least 15 billion additional cubic meters (bcm) of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Europe that year. See The New York Times, “Europe and the U.S. Make Ambitious Plans to Reduce Reliance on Russian Gas,” March 25, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/25/business/energy-environment/biden-eu-liquefied-natural-gas-deal-russia.html.

-

Liquified natural gas is natural gas that has been cooled down to liquid form for ease of transport and storage. In 2013, energy company Texas LNG LLC obtained the permit to begin building a facility in the Port of Brownsville, while another company called NextDecade began plans to build terminals in the nearby area of Port Isabel. In May of 2021, pressure by Cameron County residents and other community members led county commissioners to table the project. See Port Isabel Press, “County tables LNG project after community pressure,” May 28, 2021, https://www.portisabelsouthpadre.com/2021/05/28/county-tables-lng-project-after-community-pressure/.

-

The Yellowtail Dam, located on the Missouri River in Montana, was built between 1963 and 1968 on the sacred lands of the Crow Tribe.

Related articles

-

Sky Hopinka: Film Is the Body

The artist reflects on how intergenerational suffering becomes a transgenerational reckoning, and how art can be a bridge.

Sky Hopinka

Jun 10, 2022

-

Something Beautiful Waiting There for You: A Conversation with Kahlil Robert Irving

The artist speaks about community, craft, and his exhibition at MoMA.

Kahlil Robert Irving, Legacy Russell, Thelma Golden

Apr 26, 2022