Taken for Granite: A Climber Sees Yosemite from a New Vantage Point

To mark the 130th anniversary of Yosemite National Park, “climber’s climber” Conrad Anker explores his lifelong connection to the park through photos in MoMA’s collection.

Conrad Anker

Oct 9, 2020

The granite that forms the Central Sierra Nevada mountains, and gives Yosemite Valley its distinctive bedrock, is 100 million years old. Four million years ago, the range—an oceanic plate subducted under the North American plate—began to grow. The intermittent yet persistent force of glaciers over repeated ice ages created a landscape defined by sheer walls, hanging valleys, and ethereal waterfalls.

While humans have been present in the Sierra Nevada for at least 10,000 years, established habitation in the valley began 3,000 years ago. The Ahwahneechee Paiutes and Central Sierra Miwok traded with the Mono Lake tribes to the east. The name Yosemite is derived from the Miwok word for the grizzly bear. For the 200 indigenous people of the valley, European contact proved to be disastrous. Their village was burned and they were forced onto a reservation.

Coinciding with the California Gold Rush, Yosemite was mapped and its wonders eventually shared around the world. By the 1860s photographers were capturing the magnificence of the place, and their work was instrumental in helping to create the preserve that eventually became Yosemite National Park. These early photographers travelled with horses and an array of equipment in hopes of capturing the essence of extraordinary wild places. Compare a wagon loaded with bottles of chemicals and cameras the size of tables to the cameras available today, and you’ll have a greater appreciation for these early photographers’ skill and dedication.

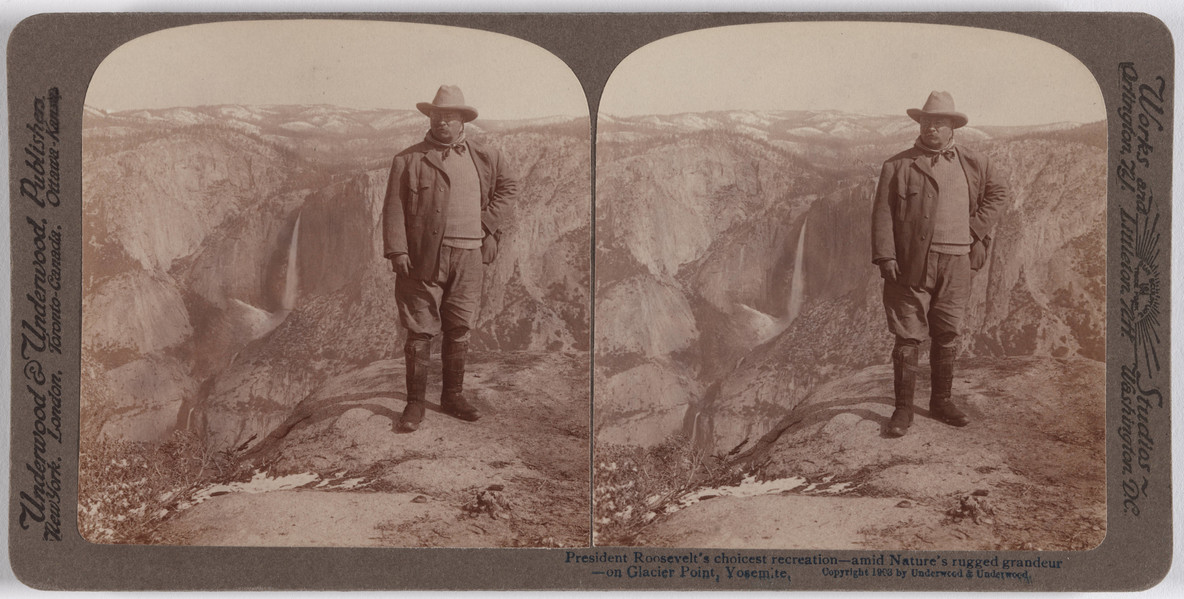

Viewed from a sequential perspective, the photographs of Yosemite from MoMA’s collection you’ll see below reflect the wonder this national park has inspired in us, and track the ways our attitudes toward it have changed. Initially these images sought to capture the park’s immensity. The photo of President Roosevelt at Glacier Point with Yosemite Falls—a ribbon of mist caught in time—galvanized a nation into recognizing the importance and urgency of preserving its natural wonders for future generations.

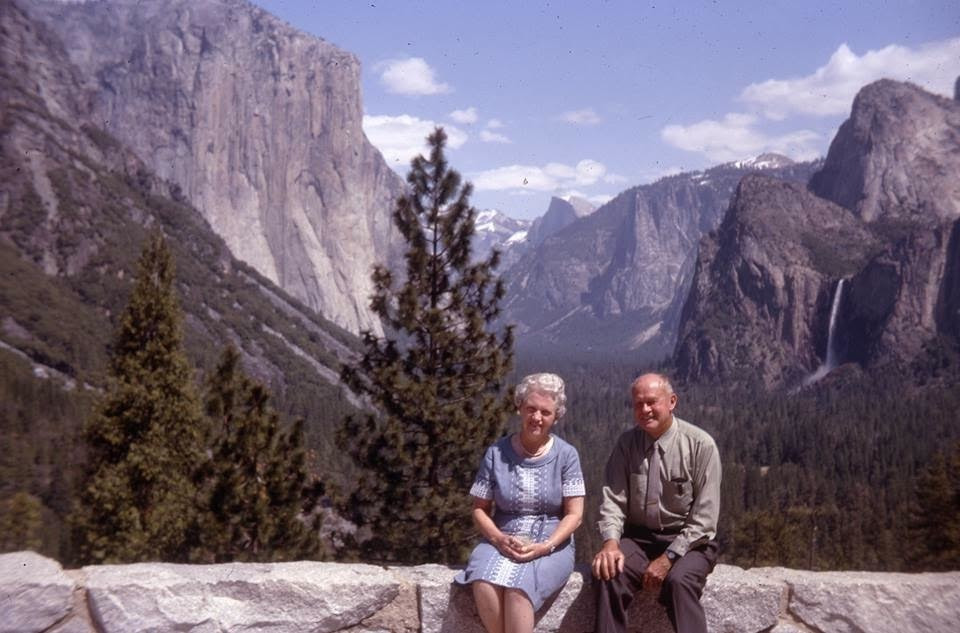

The author’s grandparents on their annual visit to Yosemite’s waterfalls

My own connection to Yosemite is threaded through my father’s family. In 1853 they settled at Big Oak Flat and started a business providing provisions for the gold miners in the vicinity. With Yosemite becoming a state park in 1864 and the opening of the Big Oak Flat road in 1874, tourism became an integral part of our family. My grandfather, Joe, worked for Hetch Hetchy Water and Power while my grandmother, Margaret, ran Priest Station, a small restaurant that is still part of our family. They would dress up in their finest clothes to watch the waterfalls each spring. When I was a child we would spend summers in the high country on extended pack trips, complete with donkeys. The time we spent in the mountains proved to be the foundation for my life as a climber. I revisit these childhood memories through images. May the wonders the photographers have preserved on film reflect the sacred connection of the Ahwahneechee. And may you find similar emotions and connections in these images.

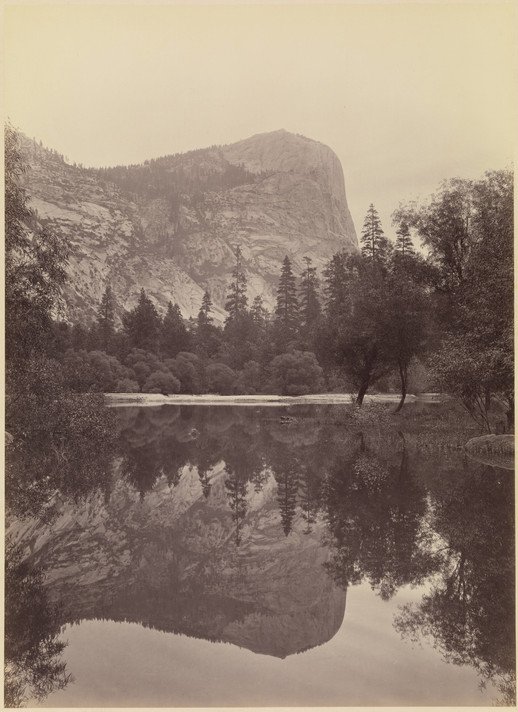

Eadweard J. Muybridge. Valley of the Yosemite. From Mosquito Camp. 1872

In the Muybridge Mosquito Camp image (above), the horizon is overexposed but the immense wall of the Valley is reflected precisely in the calm minutia of the Merced River. It is two images in one, a tranquil river lined with stately trees reflecting the disparate size of Yosemite’s monoliths.

Prior to the development of the wide-angle lens, did photographers find reflections to increase an image’s dimensions? Having two of the earliest images employ this technique makes me wonder.

Carleton E. Watkins. Mirror Lake (View of Mt. Watkins), Yosemite. 1878–81

Underwood and Underwood. President Roosevelt’s Choicest Recreation—Amid Nature’s Rugged Grandeur—on Glacier Point, Yosemite. 1903

In 1903 Join Muir and Theodore Roosevelt visited Yosemite together for a three day camping trip. Roosevelt’s fascination with nature’s grandeur and the rugged life is part of his place in history—this expedition led to Yosemite becoming a national park in 1906. The photographer placed Yosemite Falls in the background to amplify Roosevelt’s persona. Seen through a stereo viewer, for which this pair of images was intended, the illusion of depth heightens our sense of “being there” and the cavernous vista behind Roosevelt.

Ansel Adams. Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite National Park, California. 1944

If there is one iconic image that defines Yosemite, it could very well be this one. In Ansel Adams’s photograph, Bridalveil Falls is suspended in mist as dissipating clouds hint at the peaks and summits in the background. Not seeing everything at once entices the imagination; an undefined horizon invites us to possibilities of the views beyond.

Ansel Adams. Eagle Peak and Middle Brother, Winter, Yosemite Valley, California. c. 1968

Ansel Adams and Yosemite. The two are inseparable. Adams spent years living in Yosemite and photographing, and managed to capture its vast scale and detail at once. His crisp black-and-white landscapes brought attention to the park. With a studio in the valley and an ever-changing palette of colors and textures, it was Adams who brought nature photography to millions. Photographers still hike around Yosemite Valley and the backcountry to find locations where Adams clicked his camera shutter.

Edward Weston. Snow Covered Rocks, Yosemite. 1938

Two boulders, cloaked in recent snowfall, welcome the sun. Perhaps an hour later the snow condensed and the smooth transition of light on the snow was quite different. Photography captures an instant in time. The connection between subject and photographer is as unique as each person. We can look at the same thing and see different views. This image will live forever. We will not.

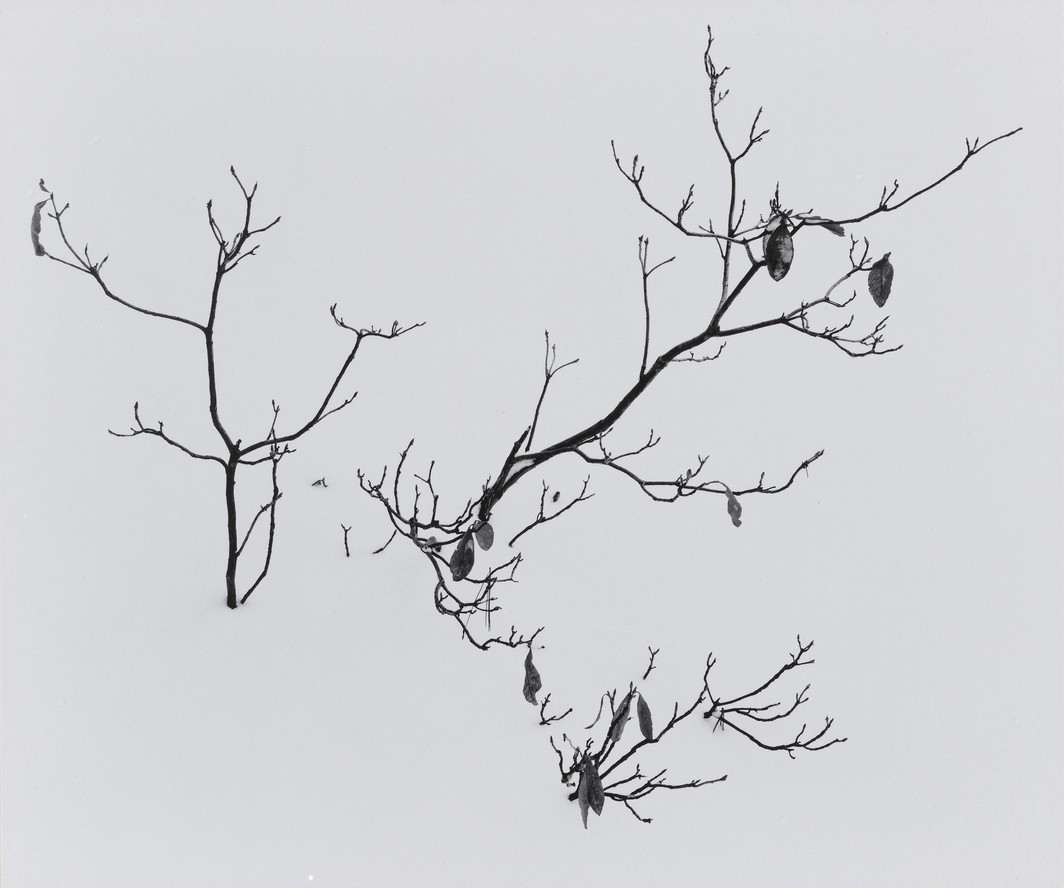

Don Worth. Winter, Yosemite. 1957

The simplicity of a dormant tree in winter is visual poetry. While a majority of these images encompass the distinctive sheer walls and towering trees of Yosemite, this one could have been taken in many places in the world. The branches dissolving into the snow bank could express winter anywhere. Perhaps this combination is a reminder of the commonality that binds nature and, by extension, human existence.

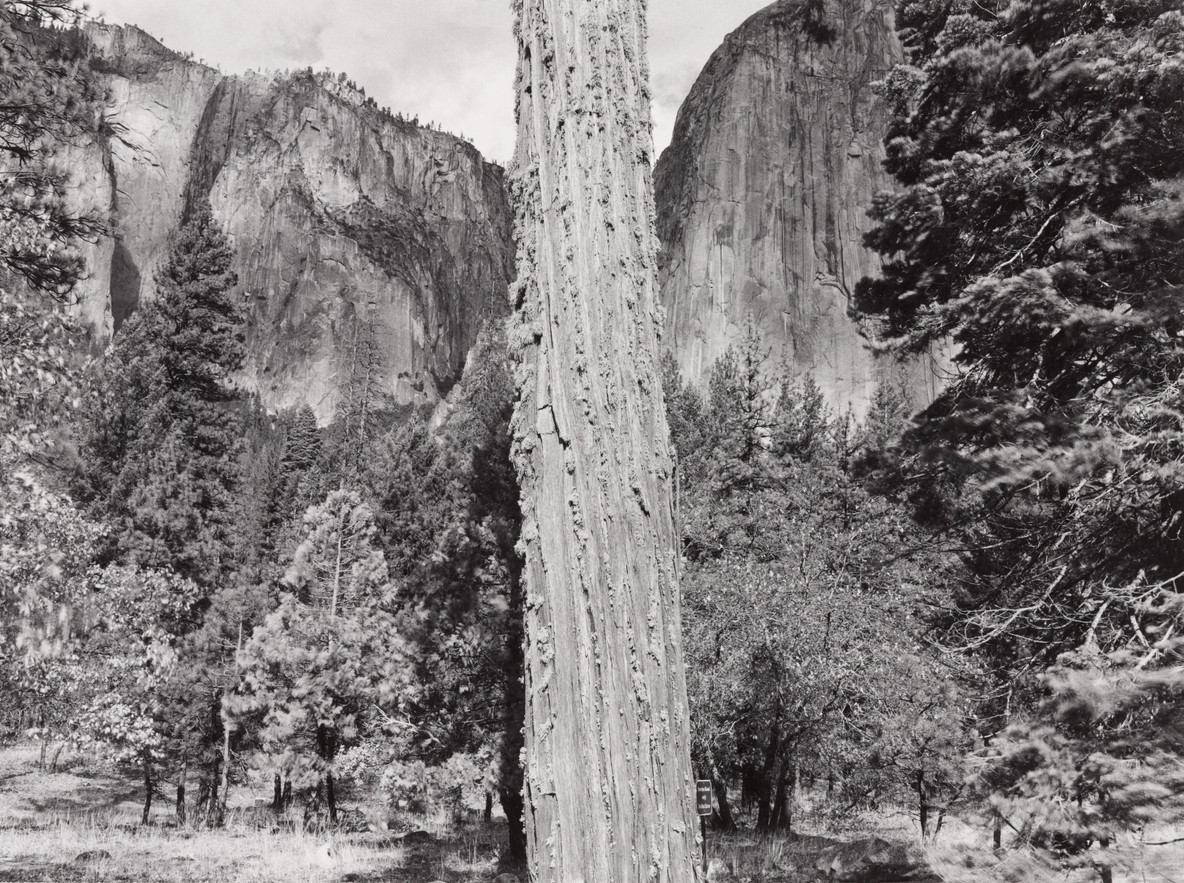

William Stephen Sutton. Tree, Yosemite National Park. 1979

One tree among many, its limbs out of frame, makes us focus on the bark. The vertical lines parallel the left side of El Capitan and the Ribbon Falls amphitheater, showing a connection between ancient rock and the transitory nature of trees.

Stephen Shore. Merced River, Yosemite National Park, California, August 13, 1979. 1979

Yosemite is a natural wonder. We see the trees, waterfalls, and walls as an amazing culmination of the natural world’s randomness. The varieties of natural landscapes are a backdrop to human visitation. When I was a child my family would visit the park each summer. We would arrive hungry for adventure, with a thirst for the unknown. Once we had our fill of bears and campfires, we would slide back into life’s routines. As a child this was school. As an adult it’s back to work. In this image by Stephen Shore, the human connection to Yosemite is what is significant.

Richard Misrach. Burnt Forest and Half Dome, Yosemite. 1988

Trees burn. We fear fire for what it can do to our treasured places. Yet it also brings life. Half Dome, the eastern sentinel of Yosemite Valley, will not appreciably change in the span of a human life. But forests will change. Fire is a reminder that we are not in charge. As the saying goes, nature always bats last.

When early photographers set out to document nature, they relayed the majesty of a location to people around the world. Looking back to the earliest images and comparing them to similar images today provides an additional layer of meaning—photographs are data that show us how the world is changing. I climb mountains all over the world and I’ve seen glaciers receding, ice climbs melt away, and the increase of dangerous rockfalls due to warming. The wildfires currently raging across the West are a result of droughts, parched forests and warmer temperatures. The solution starts with showing up to vote. We need leaders who will defend public lands, work toward keeping our air and water clean, and create jobs in a clean-energy economy. Climate change is our moonshot. We’re fighting against forces stronger than us, but we can’t quit and fire up the coal plants. We have a moral responsibility to our children and their children to vote for a better future.

Related articles

-

Artist Project

Summers and Sundays with Tina Barney

The artist looks back at summertime images from across her career.

Tina Barney, Sarah Meister

Aug 5, 2020

-

Gordon Parks: Seeing Color in Black and White

The groundbreaking photographer compels us to look beyond easy categories.

Sarah Meister

Jul 14, 2020