Framing Reproductive (In)Justice: A Picture Perfect Gruesome Negress Hurt-story

Inspired by works from the collection, author K. Melchor Quick Hall pens a poem about Black motherhood.

K. Melchor Hall

Oct 2, 2020

I first encountered writer and professor K. Melchor Hall’s work last year at Black Portraiture[s], a conference organized by photographer Deborah Willis. Appearing on a panel titled “On Black Death,” Melchor Hall read a personal essay, punctuated by excerpts from Lose Your Mother by Saidiya Hartman, about radicality of Black motherhood in the face of ancestral trauma and her experience with her daughter and the foster care system.

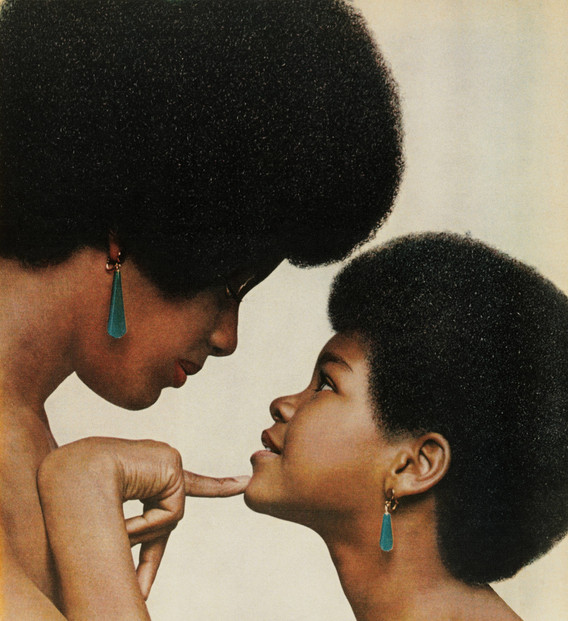

I find myself returning to her words frequently as I encounter pervasive images of grieving Black mothers like Tamika Palmer, Wanda Cooper-Jones, Samaria Rice, and so many other Black women, from Breonna Taylor on the cover of Vanity Fair to protestors standing together in the face of injustice. Unfortunately, and unsurprisingly, the virality of an image has not led to justice or a renewed commitment to protecting Black life. Melchor Hall chose two works from MoMA’s collection— Hank Willis Thomas’s Kama Mama, Kama Binti (Like Mother, Like Daughter), and Kara Walker’s Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred b’tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart—as the inspiration for this poem about the harsh realities Black mothers must teach their children in a nation that values their images more than their lives.

—Hanna Girma, Content Producer, Creative Team

Framing Reproductive (In)Justice: A Picture Perfect Gruesome Negress Hurt-story

Your government captors promised you

A new and perfect mother, to model yourself after

But your dreams have been deferred, touched up and framed

It’s been five years, and you are ready to explode

What you got in place of your picture perfect mother was me

Black and unfamiliar

Same skin, but different food, different clothes, different art

Same skin, but different language, different religion, different customs

When you look at me, you can see that I am not your mother

When you look at me, you can see that I am your mother

Look at me. I am your mother!

Loretta Ross says reproductive justice isn’t just the right to have or not to have a child

It’s the right to raise a child in a safe environment

Your mother didn’t have (reproductive) justice

No Negress in this country ever did

Because you/we/she are/is not safe, they took you from her

Because you/we/she are/is not safe, I lost you to them

They mark you as unsafe, so they can continue to hold you

Which they pretend is for your own good, which is for their own profits

The more unsafe you are

The more of their drugs they can test on you, the more money they pay themselves for keeping you

Your safety is not profitable and your freedom is not tenable

It is easy to get lost in this picture, perfectly framed, yet missing the essentials

It is difficult to get lost, searching for your safety

Sometimes mothers have to miss(place) daughters

As we pray that our daughters find freedom, in flight

Toni Morrison wrote to us about this kind of freedom, about our Beloveds

Told us about Sethe, and the daughter she had to let loose, and lose

The daughter who was lost, but never Gone

I planned your departure as freedom runs are planned, carefully, attending to nature’s cycles

On a New Moon, I told them that I would no longer be your mother

Forcing them to work to find you your happy ending

The kind they promised you, the kind you find in romance novels

Where lovers kiss under a full moon, by the waterside, where the heroine is swept off her feet

Now that we are free, of each other, and forever bound

I must tell you, what I did not say in front of them

For fear that they would think, I was like you, unsafe, in need of restraint

Even if somebody puts a pretty frame around them

Or puts them in decorated boxes

Our lives are not neat

So when someone hands you a framed picture

You must remember that there is more to the story

They call it cropping, we call it amputation

But if you look to the edges of the frame, you will know that something is missing

Hank Willis Thomas. Kama Mama, Kama Binti (Like Mother, Like Daughter), 1971. 2008

Last time we spoke, you said that you were learning the water cycle

Study nature closely

They will teach you that what goes up into the sky, returns through the rivers

Sometimes it’s the other way around

And what gets dragged through the water, ends up in the heavens

They will skip many lessons, about trees, and strange fruit

About oceans, and dangerous crossings

About the light of full moons, and the darkness of new ones

You must study nature’s cycles, to learn more than they teach

And once you begin to truly understand nature’s cycles

Maybe you will understand, that I had to lose you

And that you were not the first child I’ve had to lose

That I had to give you a chance of freedom, of flight, because I know what awaits you here

Your captors are (mostly) friendly, which they call kind

In order to balance

That they are also (mostly) racist, which they call law-abiding and well-disciplined

Several months ago, the white woman, who calls herself your teacher

Made you promise “to spread kindness and not contribute to racism and predjudice”

You might decide to teach her to spell what she cannot write and will not right

She made you write “three things you can do this week to add kindness to the world”

As if your kindness can undo their violence

They feign surprise at these 2020 racial uprisings, but your elders remember similar uprisings

Tear gas has replaced water hoses, tasers have replaced billy clubs

An unnatural cycle is repeating

What you must remember, Beloved, is that for us

This violence is always intimate

We feel it tingling between our legs, as our lovers disclose their rape fantasies

Remember when you told me and grandma that you wanted to be a stripper

And asked if strippers get raped

I heard your surprise, and a tinge of disappointment

When I said, anybody can be raped

Job doesn’t matter, outfit doesn’t matter

What matters (unfortunately), is intimacy

We will know our rapists, we will recognize them, even though we will not recognize them

I know that you are struggling with tingling feelings

In a place where your affections are rejected

Where you are kept from boys, and punished for kissing girls

It is a peculiar logic, that intends to punish, the queer Black female body

You must remember, that their romanticized rape stories

Leave much out of the frame, amputating our bodies

Follow the moon cycle, my Beloved

And when you can

Escape, on the night of a new moon

Escape, however you can

Even if you have to fly, just go

Follow the wind, ride on the wings, of those who went before you

You might feel lost

They might report that you have Gone

But I am always with you

Look for me

Look at me! I am your mother.

And we will be free

Kara Walker. Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred b'tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart. 1994

K. Melchor Quick Hall is the author of Naming a Transnational Black Feminist Framework: Writing in Darkness, and host of the companion online series of conversations with Black feminist artists and activists. She is a faculty member in the Human and Organizational Development programs in Fielding Graduate University's School of Leadership Studies. Hall is also a Resident Scholar (2020–23) at Brandeis University's Women's Studies Research Center, a Visiting Scholar (2020–21) at York University's Centre for Feminist Research, and an instructor with Boston University's Prison Education Program. Beyond the academy, she is a member of the Soul Fire Farm Speakers Collective, which speaks out against racism and injustice in the food system, and the Northeast Farmers of Color network, which is fighting for land-based justice and redistribution for Black and Indigenous communities. She also leads a Black women's writing workshop and a reparations workshop for US-based, white inheritors of wealth at Pendle Hill Quaker Retreat Center.

Related articles

-

Artist Project

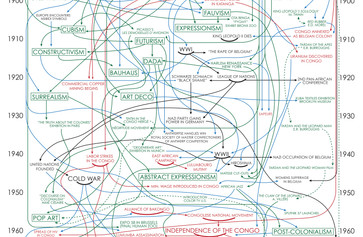

Hank Willis Thomas’s Colonialism and Abstract Art

The artist reimagines Alfred H. Barr’s “Cubism and Abstract Art” diagram.

Hank Willis Thomas, Sarah Meister

Sep 15, 2020

-

Poetry Project

Elegy for Us

Poet Crystal Williams finds truth in Faith Ringgold’s American People Series #20: Die.

Crystal Williams

Jan 7, 2020