Akram Zaatari and the Arab Image Foundation

In this interview from 2013, the artist discusses his work and the beginnings of the Beirut-based photography archive.

Eva Respini, Ana Janevski

Aug 26, 2020

This interview with Akram Zaatari was conducted via email in April 2013 by curators Eva Respini and Ana Janevski, on the occasion of the exhibition Projects 100: Akram Zaatari. As the offices of the Arab Image Foundation (AIF)—of which Zaatari is a cofounder—were severely damaged in the massive explosion that rocked Beirut on August 4, we are re-presenting a portion of the original discussion that focuses on the origins of the AIF and Zaatari’s work within it.

Eva Respini and Ana Janevski: What was the artistic climate when you came into being as an artist, and who would you say was instrumental to your thinking and practice at the time? You worked in the television industry for some time. How has this influenced your work?

Akram Zaatari: I’ve always wanted to study film, but for many reasons I studied architecture, and I do not regret it. I finished high school in 1983 when Saida (my hometown) was under Israeli occupation. My parents didn’t want me to leave the country, and there were no film schools in Lebanon. I graduated in architecture from AUB (American University of Beirut) in 1989. I worked as an architect for two years, and taught photography classes at AUB before I left to New York in 1992. I ended up doing my master’s in media studies. I never studied photography but practiced it without calling myself a photographer, without knowing where I was heading.

Although most of my references in pop culture came from Egypt, most of my references in art were European filmmakers, mainly [Rainer Werner] Fassbinder and [Pier Paolo] Pasolini, the early Wim Wenders and the French Nouvelle Vague. In the 1980s, I got fascinated with Abbas Kiarostami’s work, mainly for the way he mixed, or even melted into social situations around him to produce cinematic works totally about cinema and the living. Back then I would never have imagined that one day I would call myself a documentary filmmaker. In the 1990s I discovered [Jean-Luc] Godard’s later critical works in video and film. He is someone whose work has been instrumental for me on so many levels, from the understanding of the relationship of cinema to war, to his way of molding film, sounds, images, past present, in one body.

I returned to Beirut in 1995 to work as a producer of the morning show Aalam al Sabah at Future TV. The station was a young structure that attracted most of those who had studied abroad and decided to return to Lebanon after the official end of the civil war. I was able to make many short videos at Future TV. They were very free and unformatted pieces—in between short films, documentaries, video essays, and formal explorations. I don’t think television impacted my work in a direct way, but I think it provided me with access to the social and political reality of the country. I considered those films stolen from television, in the sense that normally I should not have been permitted to make them, but I did.

You were one of the cofounders for the Arab Image Foundation, which is not just an important archive in the Middle East, but also a source for much of your work. Could you tell us about its beginnings?

The archive of the AIF is not a source but an outcome of a research project that I largely contributed to on photography in the Middle East and North Africa. I do not use existing archives as sources for developing work. I would like to be precise that my work aims to bring to light stories, experiences, and documents, and so many links within all of them. So the work generates collections of documents, records mainly photographic, which are kept by the AIF. It is not the other way around.

AIF was created with many movements in it. It could have ended up simply as an image bank. My involvement in research projects, besides acting as president of its board for 13 years, marked AIF’s path after the first two years. That reflects mainly in the weight given to extensive fieldwork while working on art projects that communicate or present them at the same time. This dual focus, research/art project, dominated AIF’s practice from 1998 until 2010. That was the time when I researched the theme of the vehicle and made The Vehicle: Picturing moments of transition in a modernizing society (1999) and later, together with Walid Raad, we made Mapping Sitting (2002).

Reflecting on its history today, I consider that the initial goal of the foundation was a bit naïve, but proved to be not so unproductive: we wanted to be able to recount, one day, a history of photography in the Arab region. AIF did not exist as an archive before individual artists expressed the desire to create a collection and work on it, work with it. AIF therefore reflects the concerns and desires of those behind it.

Now the question is whether AIF’s collection is, or is not, an archive, and what it means or entails if it were or not. I believe there is a fundamental difference between archives as collections of “sediment”—repositories of images of various practices in an institution—and what we do as individuals, as artists too, with AIF. If you want to consider AIF an archive, I would say it is more an archive of research and collecting practices than an archive of photographic practices.

In many ways, you work as an aggregator, a collector—one could even say curator—as much of your work has taken as its starting point pre-existing archival photographs, studio images, and documentary footage. The archive of portrait photographer Hashem el Madani, who is from your hometown in Saida, has been a rich source of creative activity for you. Can you talk about your relationship to the authors of these images, in particularly Madani?

Anything pre-existing around me is an extension of my experience, knowledge, and perception, and could possibly end up as a subject for my research and in my work. There are so many people who took pictures in the 20th century, and most of these practices interest me. My relationship to authors of individual photographs is one of research in addition to the contractual side, with the exception of Madani, with whom I have a human relationship in addition to those. I spent so much time with him and know so much about his family, his work, and his life. Madani himself became part of my work, and not only his photography. I am interested in his work because I am interested in Saida’s history, on one hand, and because I am interested in taking an entire archive as a source to write the history of an industry a practitioner and a city.

I met Madani in 1998, and I became interested because he was not a perfectionist, “high-end” photographer. He produced many images that look poor from a technical perspective when compared to the work of his peers in urban centers like Beirut, Tripoli, Cairo, or Alexandria. Madani’s compositions were not complex: his subjects were usually placed right in the center of the frame, shown from head to toe. He rarely bothered with mannered or excessive lighting. In his early years, his shadow would fall onto his subjects because he would photograph them with the sun low behind him. (I find it amazing to see a photographer make mistakes that directly affect the shape of images!) But then...you could see him improving over time, learning more and more. Madani did his best to establish a kind of signature style to differentiate his product from other people’s. He took as many photographs as he could, all the while expanding his address book and adding clients to his growing archive.

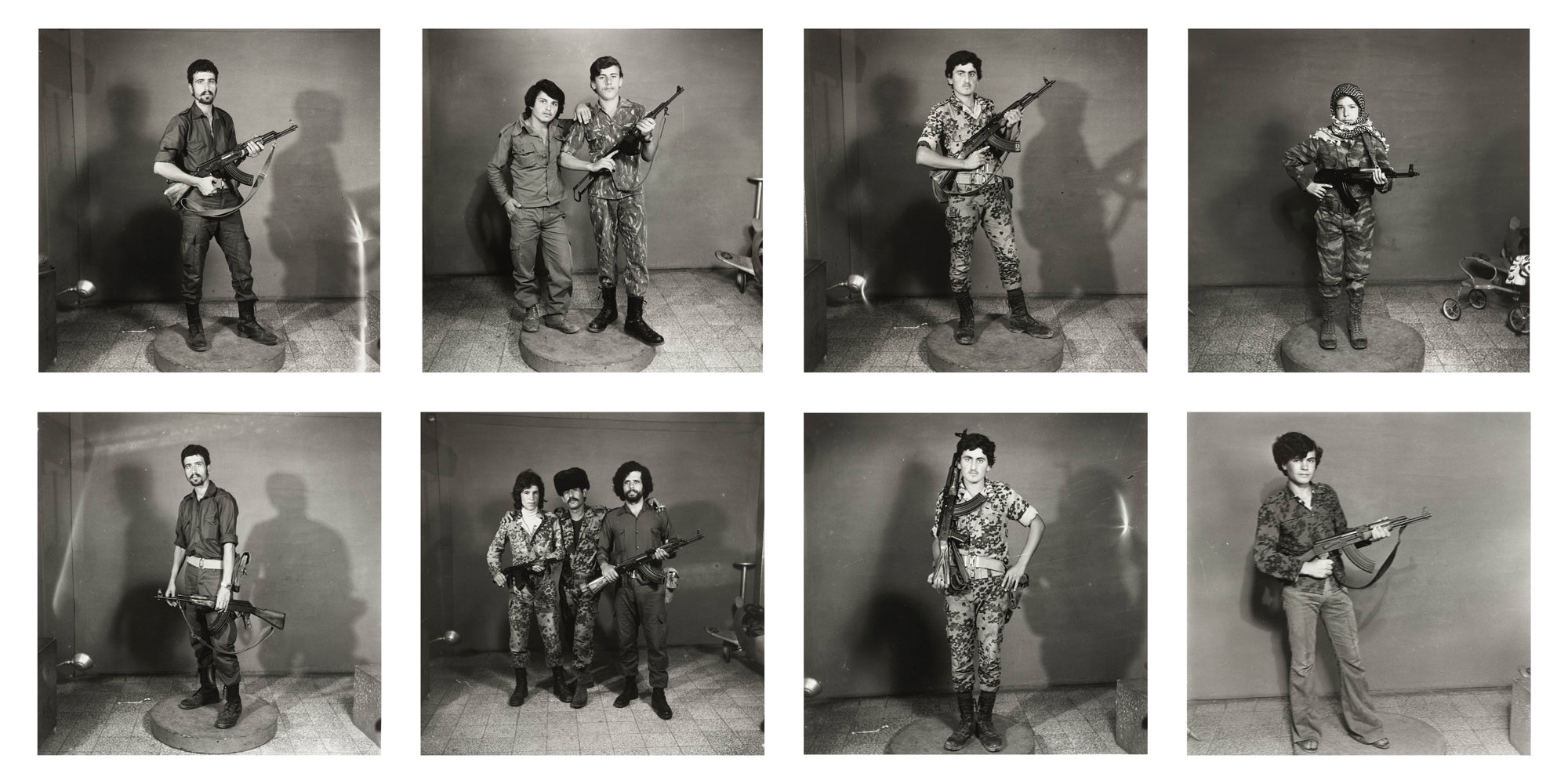

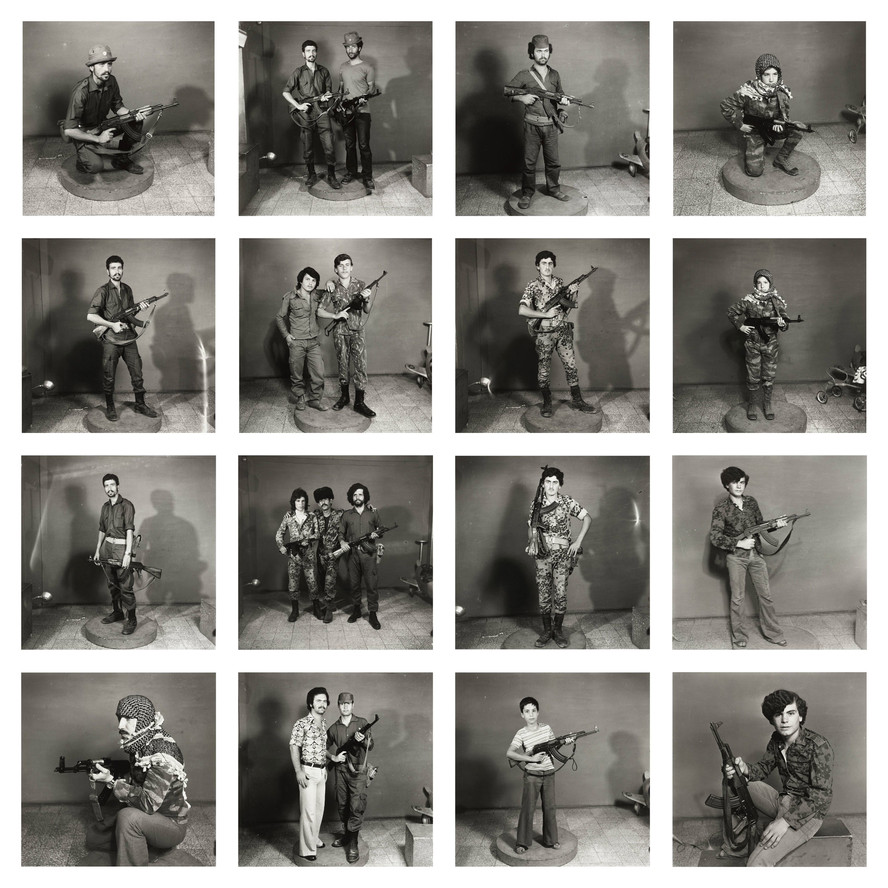

Akram Zaatari. After They Got the Right to Arms. Fourteen young men posing with guns*. Early 1970s/2006

He took pictures both in the studio—Studio Shehrazade—and outside, in public spaces or workplaces. He photographed by day and developed by night, seven days a week. He took pictures of weddings, burials, circumcision celebrations, festivities, political demonstrations, election rallies; he traveled with people who wanted a photographer

along on day trips. He cared about the quality of the image, his prints were well developed, and he wanted his prices to compete with other studios in town—so he privileged the 35-millimeter camera over heavier photo gear, and relied on this format for most of his outdoor photography.

A few years after I met him, I realized that my own interest in researching photographs was shifting, and that I was not looking for individual images of particular significance only; rather, I wanted to understand how Madani worked and how he made his choices. I was interested in how he used his studio, how he treated his clients, what kind of transactions took place there. I was also trying to understand why this profession was dying. This is how I decided to take his entire studio as a repository of transactions and records, and to target it with projects, a series of exhibitions, publications, and videos that would communicate an understanding of how photography has mixed with society throughout modern times. Studio Shehrazade still exists today partly because of an art/study project that considers describing his collection, preserving it at once as capital and as study material.

Your work (in still and moving images) in many ways can be thought of as documents for writing history. There is an idea of excavation and mapping different ways of recording during war, such as This Day (Al Yaoum) and In This House. Can you tell us how you see your works in relation to the writing and retelling of histories?

Much of my work indeed is how personal narratives meet historical moments. It is a way to look at the how moments in history translated into the micro, into people’s day to day. It is exactly like looking at family pictures of people in the 1950s and looking at how values of modern times seem to infiltrate people’s lives.

I am interested in the mechanism that makes an image what it is, even when that mechanism is a total accident, or when images come to be what they are for purely economic reasons—that would be even better. I am after learning, and I cannot learn from something that was made to follow canons. This is why I was interested in the photographer Hashem el Madani, because he was self-taught and because I can learn from his simple, spontaneous reasoning. I agree with you that there is a lot behind someone’s attitude facing a camera, not only ideology, but a universe of factors, a matrix that makes the image end up looking the way it does. The fact that this happens today without a facilitator, without that medium that used to be the photographer, multiplies choices and accidents and makes self representation go completely off canon. On the one hand, the images get wilder, but on the other—and thanks to instantaneous spreading—dominant types get to reproduce much quicker than before.

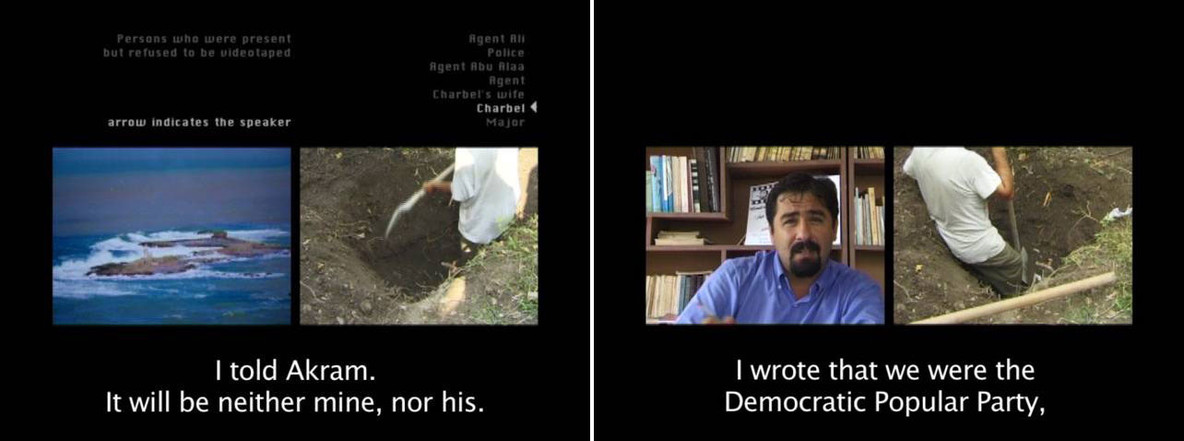

Akram Zaatari. Stills from In This House. 2005

The marketing of digital cameras and phones, and the ease and immediacy with which images circulate, certainly represent a revolutionary phenomenon in the history of image production and diffusion, and that will definitely impact not only how images look, or how they are constructed, but also our logic, our human relationships, our recording habits, or simply our lives.

Your work is often discussed in the context of a number of other Lebanese artists that explore similar issues in their work—can you talk about your relationships to these other artists and how you see your shared artistic interests?

There is a community of artists who share a common interest in writing history, in the tectonics of storytelling, in identifying and producing documents taking the war situation as a case or a base, not because they are interested in war as a subject, but because war is one of rare situations where notions of common logic collapse, and the notions of evidence in relation to documents and history are challenged. Among this generation you see very often ideas circulating, getting commented and challenged further from artist to artist. You see ideas echoing other ideas very often. There are common features very visible among that constellation of artists, but there are more and more differences between their approaches or politics.

AIF was a product of a contemporary art movement in Lebanon in a certain political and historical context, and it seems that your attitude has changed since then. In one of your interviews you are talking about the anxiety of keeping an archive or being “against photography.” On Photography, People and Modern Times in many ways seems like the final chapter of your work with AIF. Can you tell us about the genesis of this work and the shift that this video represents?

The idea behind the Arab Image Foundation was to establish a collecting mechanism and a study platform. For me, it was meant to be first a learning experience, culturally, and then a preservation project. When I started traveling, looking for photographs, I was eager to discover what was out there that had been inaccessible to me. I was guided by the possibility of discovery, and that possibility cannot keep on occurring when you do the same thing over and over for years, in the same territory and using the same tools. I tried my best to shift my work, like while studying Studio Sehrazade, away from photography to focus on the life and context in which it was born, to include more recent studies that include the Internet and images that could be gathered from social communication sites, but I could not raise the interests within the foundation towards those ideas.

The work that you are showing at MoMA, On Photography, People and Modern Times, addresses the magnitude of my discoveries while researching photography’s history in the Middle East. In it you feel my more recent reservations about photographic preservation. The video closes with an interview with Armenian-Egyptian photographer Van Leo during which I try to convince him to donate three additional pictures to AIF while he is trying to avoid answering. Van Leo’s hesitation communicates a fear of parting from his images, perhaps because he knows he will soon die: should he agree to give away his archive while he’s alive, or stay with it, at the risk of it being dispersed after his death? It is a fundamental open-ended question about preservation.

I recently proposed to the board of AIF that we should offer to return collections to their respective families. There are many facets to this proposal. With passing years, I realized that the foundation does not need original documents to write history, especially now that scanning technology allows us to do what was difficult to do in the mid-1990s. We always insisted that we were interested only in originals, because our interest lies in photographic preservation. I don’t believe in this anymore, because I don’t see the preservation of photographs as preservation of material only. It would be interesting to determine what exactly is essential to preserve. If emotions can be preserved with pictures, then maybe

returning a picture to the album from which it was taken, to the bedroom where it was found, to the configuration it once belonged to, would constitute an act of preservation in its most radical form.

I thought that by taking the same path we took in 1998–2000, when we collected so many photographs from the Middle East, and reversing its direction by returning collections as opposed to taking them away from their owners, we would be most likely able to have new encounters with new people, get in touch with new ideas, new questions regarding the function of photography in people’s lives now. Moreover, I thought we could start or join an international debate around archives and the places they come from. There is a fertile ground for those ideas in the world today, I think.

I would have loved the AIF to engage with the questions that interest me today in photography and in preservation, but I think it is not ready yet. For this reason I suspended my membership and withdrew from the board. However this is not the end of my relationship with AIF, I simply do not want to be in it, but still have projects running, where AIF is partner, namely my work on the archive of Studio Shehrazade. And those will not stop. There are plenty of chapters of that project in the horizon and I hope to be able to continue this work with the AIF.

Read a new interview with Akram Zaatari, Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh, and Rachel Tabet, in which they discuss the Beirut explosion and the future of the Arab Image Foundation.

Related articles

-

A Call for Beirut

In the wake of the Beirut blast of August 4, Akram Zaatari, Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh, and Rachel Tabet discuss their city and the future of the Arab Image Foundation.

Clément Chéroux

Aug 28, 2020

-

Resources

Support the People and Culture of Beirut

An incomplete list of initiatives to help rebuild Beirut and aid the people affected by the August 4 explosion

Ruba Katrib

Aug 26, 2020