Pandemic Time

Five works consider the elasticity of time.

Romy Silver-Kohn

Jul 23, 2020

As many of us begin to emerge from our homes, placing one tentative foot in front of the other, it can feel like exiting a time warp. At various moments over these past few months, in the midst of seismic and at times devastating events, time seems to have stopped, bent, or become caught in a continuous loop. This feeling spurred me to consider how artists have reflected upon the sometimes absurd, maddening, and heartbreaking aspects of time in their work, and how they have used it to find control, solace, and catharsis.

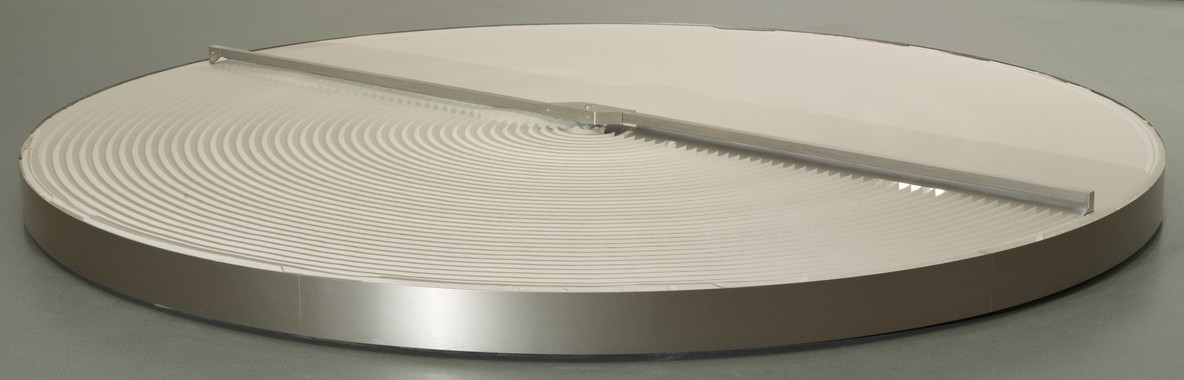

Mona Hatoum. + and -. 1994–04

Shrinking our worlds to our homes and a short radius around them has had the effect of making each day feel like a continuation of, or another try at, the previous one. The 1993 film Groundhog Day comes to mind again and again. In Mona Hatoum’s + and - a motorized metal arm, half serrated and half smooth, rotates over a circular bed of sand every 12 seconds. Each time a mark is made, it is systematically erased, and made again. We wash the dishes; the sink fills up. We do the laundry; the hamper is full. We go to sleep, we wake up, the day begins again. The cycle of creation and destruction in Hatoum’s work echoes the relentless repetition of tasks never truly finished, and the unceasing historical pendulum swings of violence and protest, progress and regression, reminding us of our lack of control.

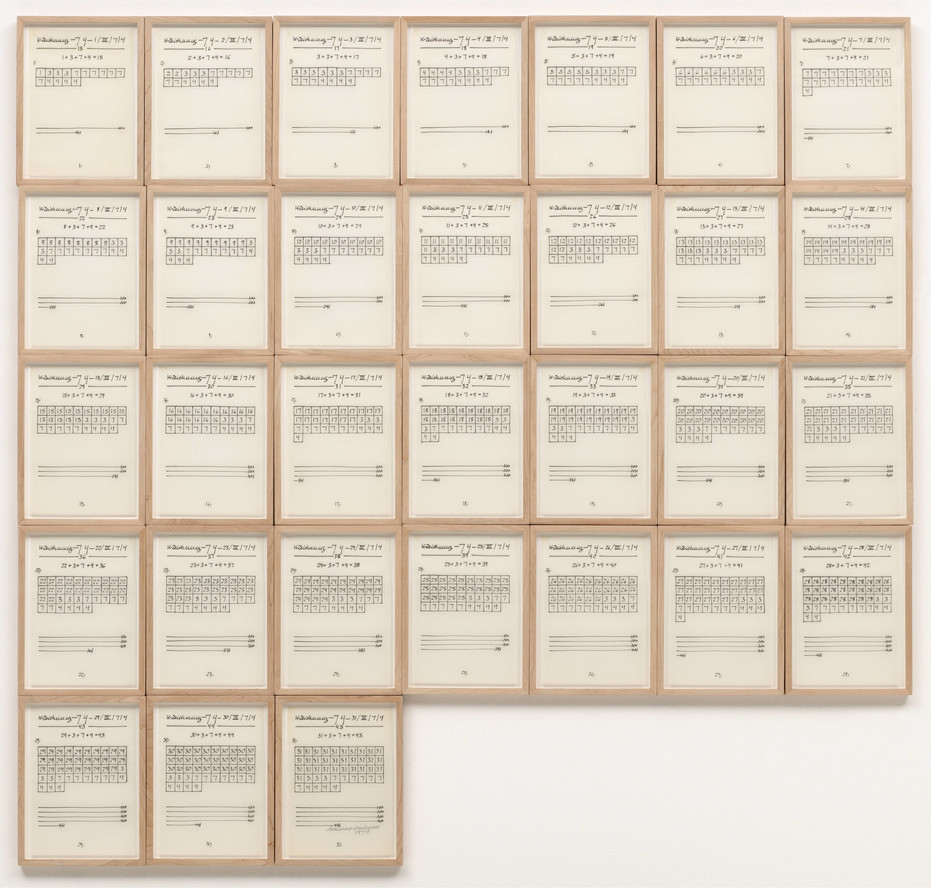

Hanne Darboven. Month III (March). 1974

Hanne Darboven’s Month III (March) is emblematic of the artist’s disciplined, labor intensive, and systematic approach to art making. Like many artists working in the late 1960s and ’70s, she placed ideas and process above personal expression. Darboven developed procedures centered on the calendar in the mid-1960s, while living in New York City and working in almost complete isolation. This work, in which she adds the digits that make up a date (day + month + year) to represent each day of the month, evokes long periods of time spent alone. The artist, who considered herself a writer first, uses numbers as a way of “writing without describing.” Each sheet is like a journal entry, asserting her presence but little else. Darboven won’t let time pass without marking it, as if attempting to not be forgotten.

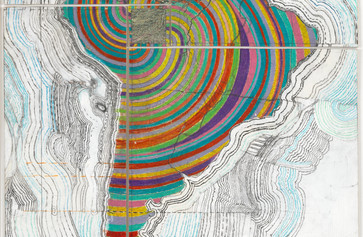

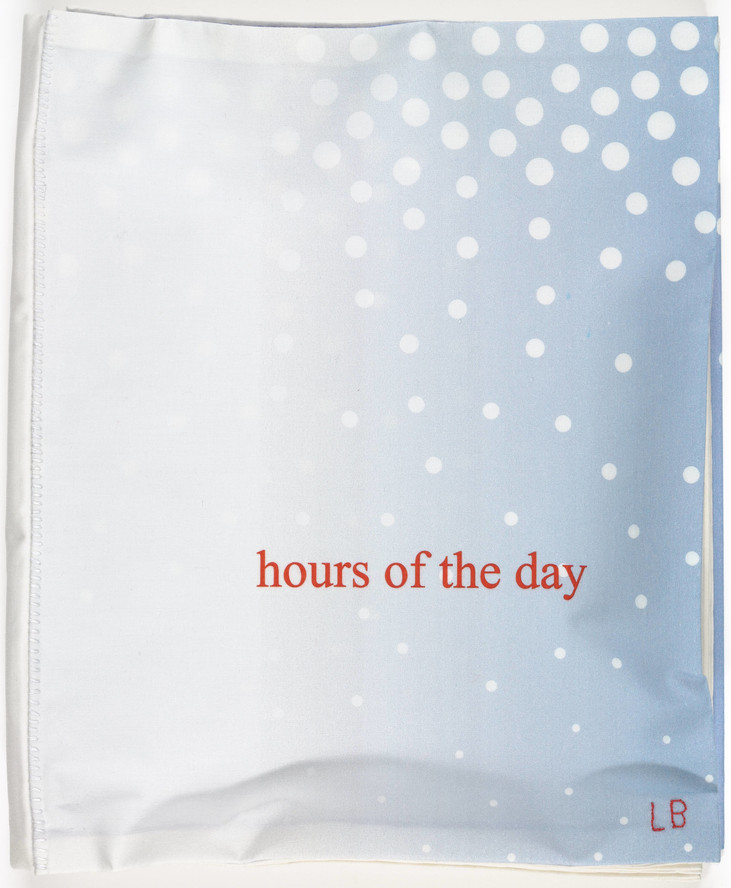

Louise Bourgeois. Hours of the Day. 2006

Louise Bourgeois’s Hours of the Day is an illustrated book digitally printed onto fabric, made when the artist was 96 years old. The title and format reference the lavishly decorated medieval Books of Hours, which contained prayers for each hour of the day. Bourgeois’s version pairs excerpts from her daybooks with an image of a clock with 24 numbers on its face. Each time you turn the page the clock strikes a new hour. The text, from various moments in her life, coalesces into a manic day. Bourgeois references house arrest, procrastination, a stopped clock. In number 11 she associates domestic work with time lost: “What did you do for twenty years? You have wasted your time, The woman who has lost her life, She has cooked, housecleaned, sewn, washed, done the stairs, the windows, the floors, the fish and the soup.” As she proceeds, her tone becomes more hopeful. In number 19 she claims time for herself: “Emptiness in time and in space, I need emptiness, The garden is beautiful and empty, My future, my days, are all clear and empty, I have time.” By the end she invokes sunrise, renewal, and a return of the light.

Henri Matisse. The Piano Lesson. 1916

Henri Matisse’s The Piano Lesson depicts the artist’s son Pierre seated at the piano surrounded by his father’s work, such as Decorative Figure (1908) in the lower left and Woman on a High Stool (1914) at the top right. The painted window opens onto a large swath of green meant to represent the garden outside. The artist balances abstraction and representation, nature and culture, emotion and reason. The work is also awash with symbols of time. The metronome on the piano brings logic and order and is a visible and audible representation of time passing. The candle is almost burnt out, a symbol of inspiration and dedication, but also a reminder that our time here is fixed. Pierre was 16 years old in 1916, though the artist made him look much younger. Matisse painted this in the midst of World War I; though he was too old to enlist, both of his teenage sons would do so shortly. The work can be seen as a defensive strategy against his boys becoming men during such a violent and tumultuous period—an effort to stop time, or at least slow it down.

Betye Saar. Anticipation. 1961

The tranquil-looking figure holding flowers echoes traditional Christian imagery of the Virgin Mary. Unlike most images of pregnancy in the history of art, however, this is a self-portrait of a Black artist, made while Betye Saar was pregnant with her third child, in 1961. Waiting is a part of pregnancy, of course; but Saar’s title, Anticipation, suggests an active form of waiting, as both mind and body work to prepare. The heaviness of the figure’s body reflects this labor. In 1961 and still today, Black bodies are not afforded the same safeguards as those of other races. This knowledge takes a toll. In Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates writes that “perhaps the defining feature of being drafted into the black race was the inescapable robbery of time, because the moments we spent readying the mask, or readying ourselves to accept half as much, could not be recovered.” Saar’s choice to represent herself as patient, unworried, can be seen as an act of defiance, despite the threat. Like pregnancy, today’s moment is defined by two states that seem opposed, but exist simultaneously. It is a time to pause and a time to act. Who knows how long we may have to remain in this period of uncertainty, and for many it is a window into the uncertainty others have had to live with all along. We all have our own work to do. This work can be as quiet and seemingly passive as pregnancy, but it must be as generative, active, and powerful as well.