Visualizing Recovery: The Federal Art Project’s Legacy in Prints

How can artists reshape society?

Margot Yale

Jul 17, 2020

Working from home as COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter protests continue to grip the country, I’ve found myself imagining how artists might be enlisted in reshaping our society and rebuilding in the wake of this moment of reckoning. These questions have shed new light on a project I began last year, to research and catalog MoMA’s holdings of over 400 prints from the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project (WPA/FAP). The Roosevelt administration established the FAP in 1935 to provide wages for nearly 10,000 artists at different stages in their careers. The program’s commitment to keeping artists on payroll as the country navigated recovery from the Great Depression is often cited as an unprecedented moment in American history, when artists and art were deemed central to economic recovery.

The FAP employed artists to work in different divisions based on medium, such as easel painting, sculpture, printmaking, and mural painting. The printmakers in the program were especially prolific: from 1935 to 1943, they produced 240,000 impressions from 11,000 different compositions, far outpacing the production of other divisions thanks to printmaking’s defining characteristic of reproducibility. MoMA’s prints were allocated to the Museum as extended loans, mostly following the government’s liquidation of the program’s assets to institutions across the country in 1943. The FAP prints entrusted to MoMA testify to an ethos of collaboration and camaraderie that enabled technological innovations in printmaking. The influence of the WPA printmakers and their ingenuity is most palpable when the FAP prints are considered alongside later prints from MoMA’s collection. Put in conversation, these works tell a vital story about how FAP artists laid the foundation for the direction of modern and contemporary American printmaking.

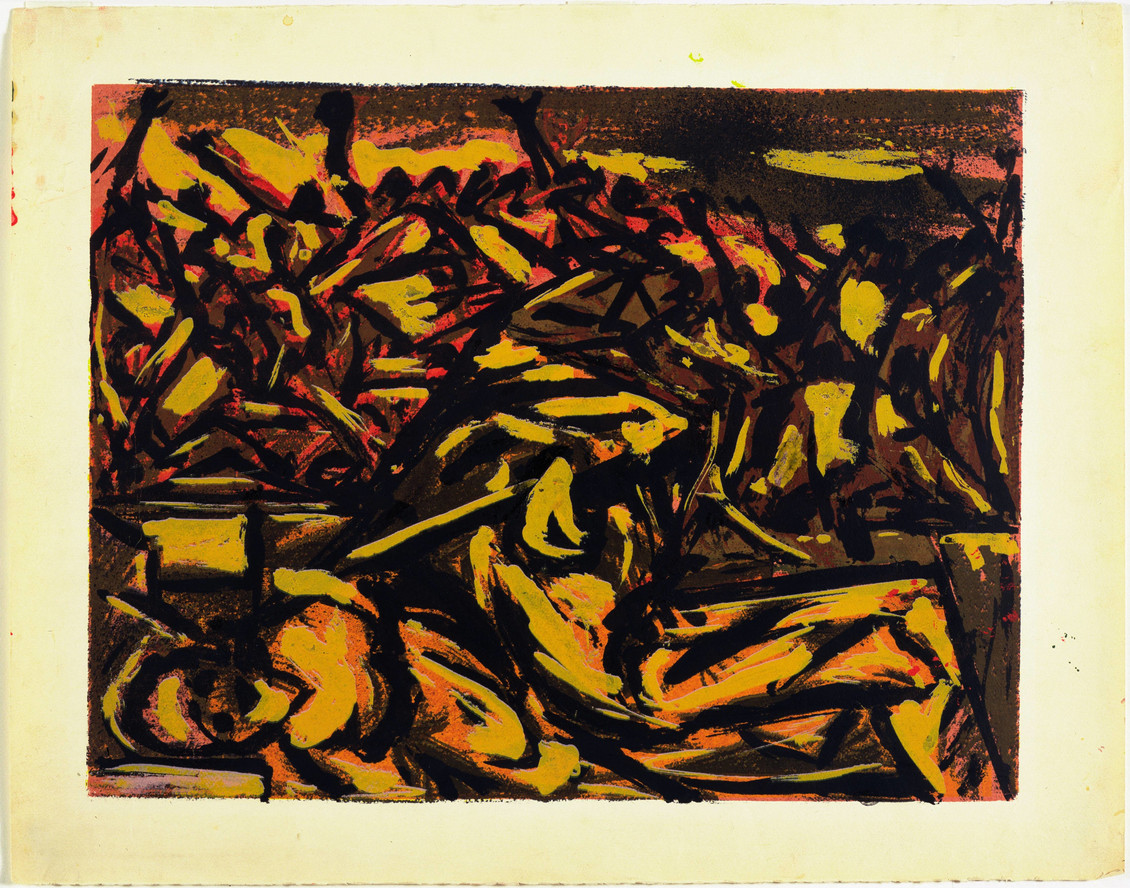

Anthony Velonis. Decoration Empire. 1939

Take silkscreen pioneer Anthony Velonis’s Decoration Empire (1939). Developed in the United States in the early 20th century as a tool for printing banners and other advertising materials, screenprinting was considered an exclusively commercial process. Velonis first learned the technique in commercial print shops in the 1920s and began experimenting in his own shop in the early 1930s. Recognizing that screenprinting allowed artists to experiment with color, hard-edged lines, and texture, Velonis helped elevate screenprinting to a recognized art form by petitioning the program to initiate a Silk Screen Unit in 1938. In Decoration Empire, Velonis pushes the medium in new directions, contrasting characteristic hard-edged lines denoting form with painterly olive passages and a sinuous ultramarine pattern cast over the blue vase, all printed through differently sized mesh screens. Velonis used this print as a teaching tool at the Silk Screen Unit in New York. In 1940, after Unit artists coined a new name for the medium—serigraphs—exhibitions of screenprints, mostly by artists working for the FAP, began to gain traction across the US.

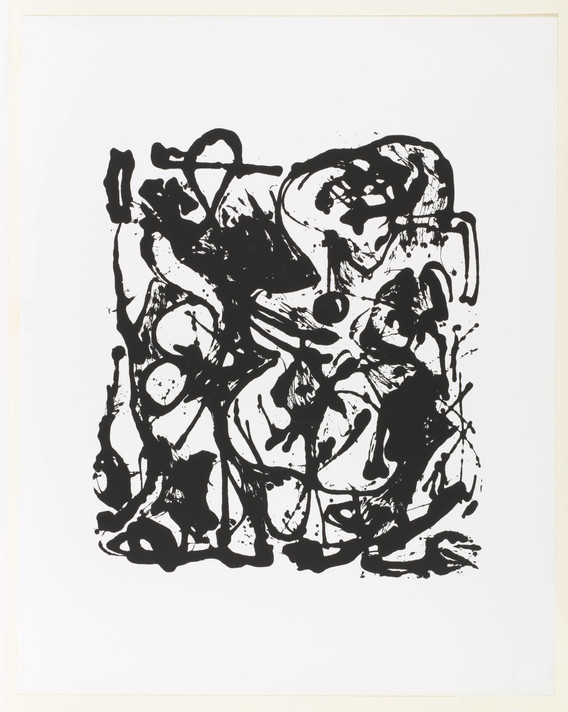

Jackson Pollock. Untitled. c. 1938–41

Jackson Pollock, who worked for the FAP from 1938 to 1942, is believed to have first encountered screenprinting on his unofficial, late-night visits to the program’s graphic arts workshop in New York. It’s not known whether he ever produced screenprints at the workshop, but he was undoubtedly influenced by the prints that he saw during his visits. In an untitled print made circa 1938–41, Pollock uses screenprinting to painterly ends, affirming the loose marks made with stencils by adding India ink and gouache by hand. Pollock returned to the medium to create a portfolio of screenprints a decade later, reproducing six of his 1951 paintings at one-quarter size and accurately emulating the effect of poured enamel on canvas.

Jackson Pollock. Untitled, from an untitled portfolio. 1951

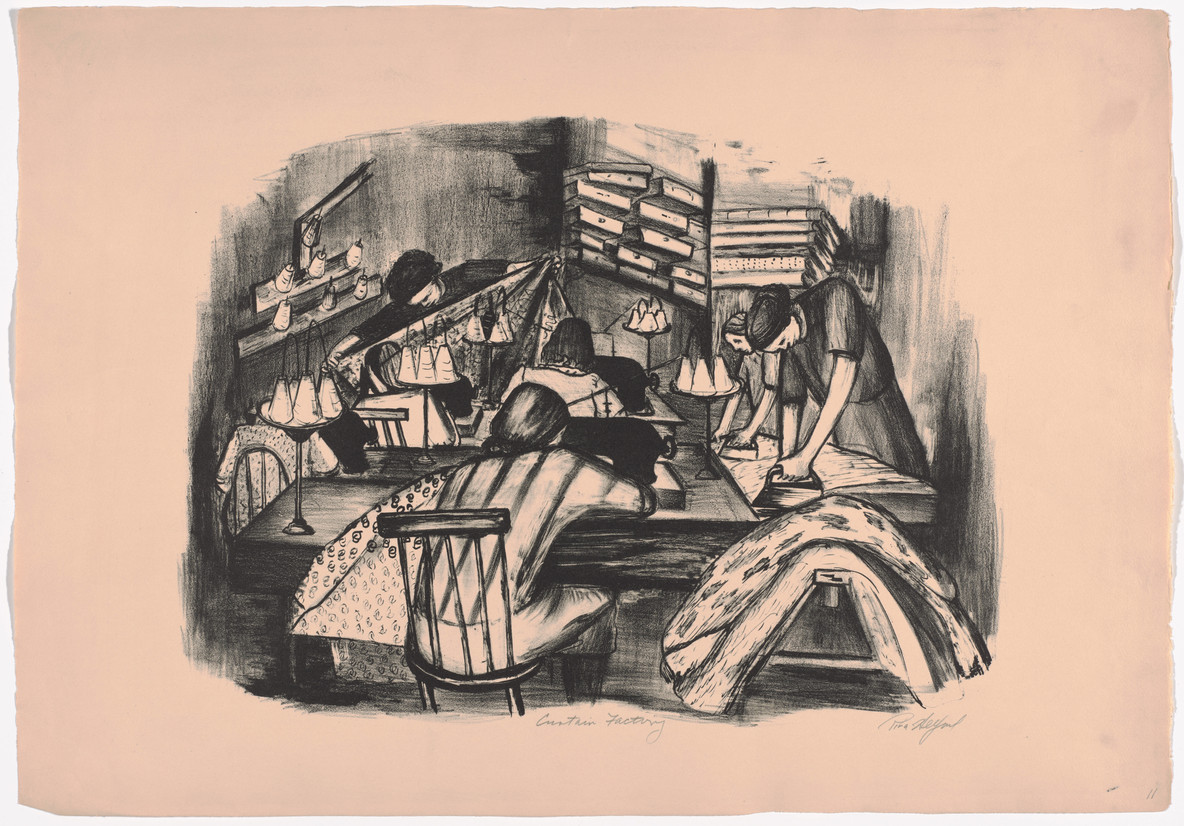

Riva Helfond. Curtain Factory. c. 1936–39

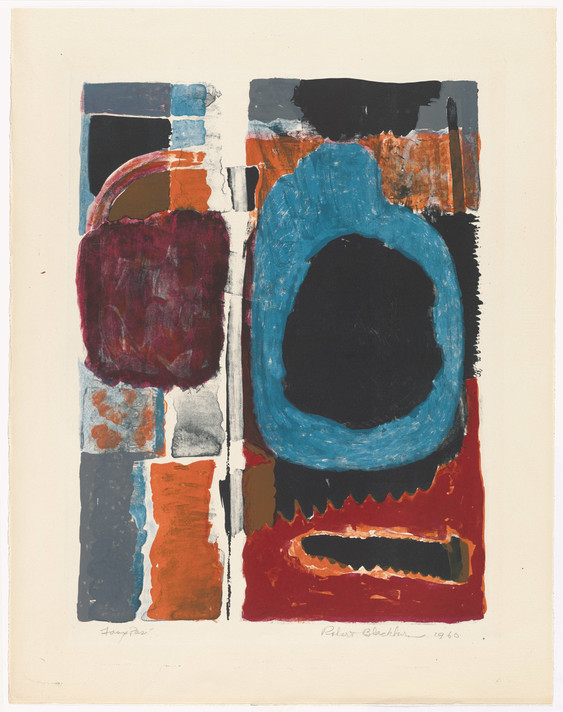

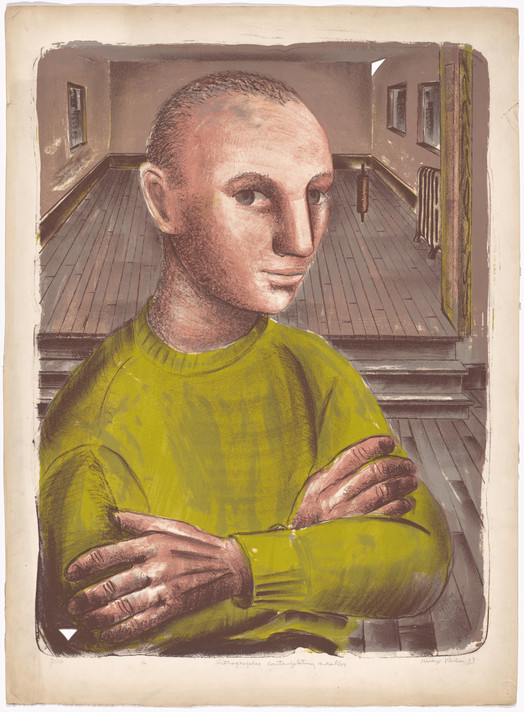

At FAP printmaking workshops across the country, artists learned lithographic techniques for the first time and, consequently, lithography, and especially color lithography, gained stature as a recognized art form in America. At the FAP’s Harlem Community Art Center—a uniquely interracial community first directed by Augusta Savage—Riva Helfond taught lithography as she navigated her own grasp of the medium. She likely made Curtain Factory, a lithograph depicting a sweatshop where working women bend wearily over their sewing machines, during her time at the Center. Helfond’s students included Robert Blackburn, an artist who would become a renowned master printer for Charles White, Faith Ringgold, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Betye Saar. Blackburn’s own prints, especially Faux Pas (1960), capture the experimental spirit of FAP lithography: Blackburn plays with the possibilities of color, overlaying different inks, and accentuates the materiality of the stone by retaining negative space in the composition’s center, referencing a lithograph he printed for Rauschenberg where the stone broke under the weight of the press.

Robert Blackburn. Faux Pas. 1960

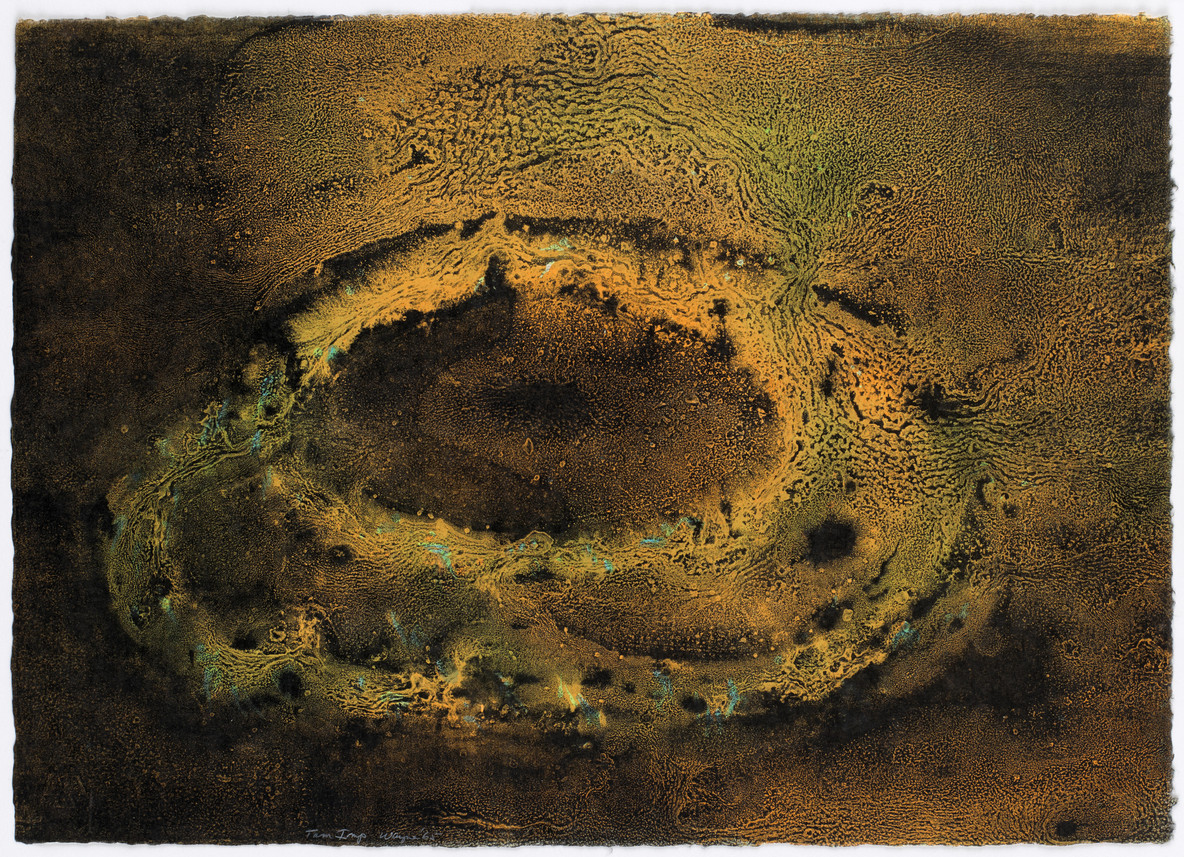

June Wayne. At Last a Thousand I. 1965

At the Chicago graphic arts workshop, artists Max Kahn and Eleanor Coen helmed the ship. While employed by the FAP, Kahn focused on honing techniques for color lithography, including one for printing multiple colors on a single stone. Kahn’s print, Lithographer Contemplating a Roller (1939), is a self-reflexive display of his assiduousness and self-assurance as a skilled printer. When the FAP dissolved in 1943, enthusiasm for lithography in the US waned due to lack of resources. It regained prestige as a printmaking technique for American artists in large part as a result of the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles founded by June Wayne in 1960. Decades before founding Tamarind, Wayne was employed by the Chicago FAP as an easel artist. Working in close proximity to other artists and printmakers in the building, Wayne was motivated by their sense of community and collective ambition. Tamarind was founded to nurture the relationship between artist and printer, and became a space for artist-fellows to pursue radical experimentation in lithography. MoMA’s complete holdings of Tamarind prints from the 1960s reflect this goal; Wayne’s prints, in particular, exhibit a commitment to experimentation exceeding that which was imaginable during the FAP. At Last a Thousand I (1965) defies all expectations of lithography: the tusche reacts with salt, water, and sand to imprint the paper with a cosmic image.

Unfortunately, a publicly funded program like the FAP seems unlikely in our contemporary climate, but the FAP’s shortcomings should not be understated. Black and white artists, for example, rarely worked together, a consequence of the endemic racism in the New Deal’s policies. The Harlem Community Art Center, founded in response to the pressure the Harlem Arts Guild put on the FAP administrators to hire more Black artists, was one of few exceptions.

Instead, what we need is a radical reimagining of artists’ role in society, and how we support their work and nurture their communities. In imagining a road to recovery from COVID-19, I hope as a society we will place value on artistic communities; given the resources, they can fundamentally alter the trajectory of our visual world.

Max Kahn. Lithographer Contemplating a Roller. 1939