Social Practice, Cuban Style

Artists rise up to protest a police killing in Havana and a government’s repressive policies.

Coco Fusco

Jul 10, 2020

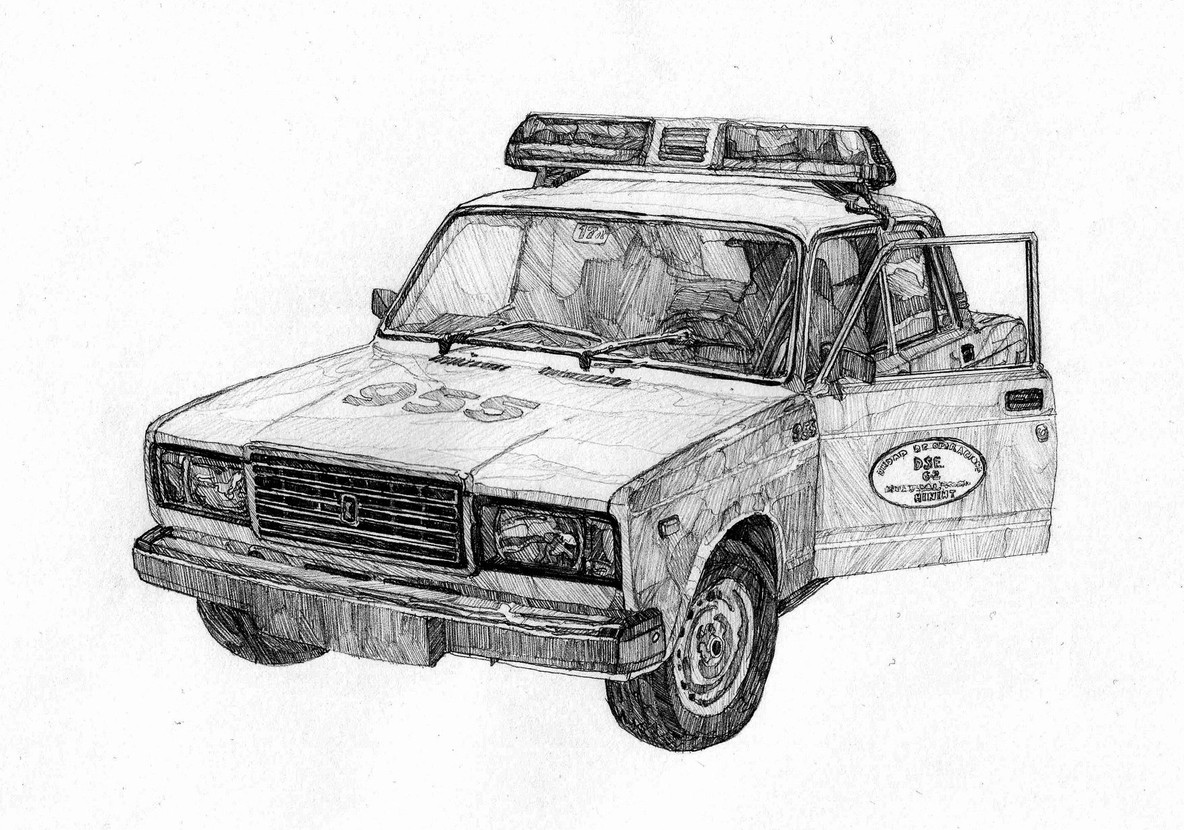

Camila Lobon’s drawing of Hansel Ernesto Hernández-Galiano, 2020

Este artículo está disponible en español.

They began their collective action in Cuba last week by posting video testimonies about their intent to protest the police killing of Hansel Ernesto Hernández-Galiano. Poet Amaury Pacheco recited the prayer of St. Francis; visual artist Tania Bruguera issued a stern warning to police; music promoter Michel Matos filmed the state security agents’ cars parked in front of his house; performance artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara sent a message of love to his Facebook followers. The victim was a 27-year-old resident of Guanabacoa, a municipality on Havana’s eastern edge, who according to the police attempted to flee when he was apprehended stealing. This wasn’t the first time that a Black Cuban died because of contact with the police, but news of the Black Lives Matter movement had reached the island and many artists believed that they should respond to state violence with a political performance. The killing had provoked an outpouring of rage on social media—the closest thing ordinary Cubans have to a public sphere. The Ministry of the Interior defended itself by issuing a public statement about the victim’s criminal record. Because Cuban authorities regularly crack down on protests, the artists and activists who called for the act of civil disobedience made it clear that they knew that they would be arrested for taking to the streets. The performance consisted of setting off that reaction.

Sure enough, arrests began at 6:17 a.m. on June 30, when police banged on Bruguera’s door. Her last text message to her sister read, “They’re taking me away.” Within a few hours, several members of the art collective known as the San Isidro Group—Pacheco, Matos, Otero Alcántara, and rapper Maykel Osorbo—had been detained. By 11:00 a.m., 45 other artists, independent journalists, and activists across the country had been arrested, and 85 more Cubans were placed under house arrest to prevent them from attending or reporting on the protest.

The designated location of the protest—the Yara Cinema on 23rd and L streets in Havana—was surrounded by police. Cubans that managed to evade the police prowled the park across the street, sending pictures of the siege. Those who were confined to their homes recorded their tense exchanges with the agents who guarded them. Friends began tracking arrests and contacting police stations to determine where people were detained. Calls went out to international human rights bodies; in a matter of hours, over a dozen organizations issued public statements of concern about the Cuban state’s interference in a peaceful protest. Even Reuters, an agency usually wary about amplifying the voices of Cuban dissidents, filed a report about the protest that made it into the New York Times. By nightfall, the majority of the detainees had been released and the extraordinary display of state force ended.

Tania Bruguera’s June 30 text to her sister: “They're taking me away.”

Mass arrests prompted by artists are highly uncommon on the island, but a growing “artivist” movement in Cuba is changing the rules of the game. “This was an exercise for us to learn how to act in a civic manner,” explained Otero Alcántara. For decades, Cuban artists who steer clear of politics have been rewarded with free promotion, permission to travel, and the right to earn hard currency, so most of them have kept quiet in order to enjoy the perks. But the Cuban government’s recent efforts to curtail the activities of independent artists and journalists have been met with increasing resistance. Over the past 18 months, artists have spearheaded campaigns against new laws that subject them to arbitrary inspections, fines, and detentions. They have also challenged the state’s harsh treatment of political prisoners. Artists have protested the mistreatment of the country’s LGBTQ citizens and launched public debates about the participation of Cuban intellectuals in the ritualized repudiation of dissident artists in the 1970s and ’80s. A younger generation of artists is articulating a different moral vision of what it means to be revolutionary, and social practice methods are essential to their projects, which take the form of workshops, lectures, debates, publications, pop-up exhibitions and political campaigns, street performances, and protests. They work collectively to thwart the Cuban state’s attempt to neutralize its opponents through isolation. Tania Bruguera noted in her comments about how Ministry of Interior officer Kenia Maria Morales Larrea treated her that the security agent repeatedly told Bruguera that she was alone and that no one paid attention to her.

In March, Cuban artists succeeded in freeing Otero Alcántara after two weeks of imprisonment; he had been falsely accused of damaging state property during an arrest and charged with flag desecration because of his performance Drapeau, in which he wore the Cuban flag day and night. A few days before the June 30 protest, Cuban biologist and human rights activist Ariel Ruiz Urquiola secured an invitation to address the United Nations about violations of human rights in Cuba by performing a hunger strike in front of UN headquarters in Geneva. He claims that he was injected with HIV while he was in a prison hospital two years ago, and that his sister, the design historian Omara Ruiz Urquiola, has been denied needed cancer treatments on political grounds.

As soon as the detainees were released on June 30, they turned their attention to the case of independent journalist Jorge Enrique Rodriguez. A collaborator at INSTAR, Rodriguez was arrested on June 28 when he attempted to record a conflict between Cuban citizens and police. He was charged with “disrespect” to Cuban authorities and faced a possible prison sentence. Otero Alcántara, together with psychologist Kirenia Yalit and biochemist Oscar Casanella, presented a writ of habeas corpus at Havana’s Provincial Criminal Court after the journalist had been held incommunicado for four days: Rodriguez was released the following day. Artists are making sure that every action and every official document they generate is carefully documented and posted to social media to ensure that this emergent but unofficially recognized civil society maintains a public presence.

Performance artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara’s post on Facebook before his arrest, which begins, “Ready to leave, I am surrounded by police and will go to prison....”

Coalitions between activists and cultural producers in a range of fields are developing out of a shared sense of injustice. Even though police frequently harass those that participate in its events, Bruguera’s INSTAR forges on with its programs, which give a forum to journalists, poets, lawyers, and artists. The San Isidro Group continues to organize exhibitions and events in the homes of its members. Independent online magazines such as El Estornudo, Rialta, and Hypermedia turn out scores of trenchant observations and commentary about Cuban culture and politics and the gross deficiencies and excesses of the Cuban state. Since the pandemic began, artist Hamlet Lavastida has been posting chilling drawings of iconic figures and commodities associated with the repressive conditions on the island, a project that he frames as an homage to Polish historian Emanuel Ringelbaum’s archive of the Warsaw Ghetto. On the day of the protest, he posted a drawing alluding to a private encounter with a policeman who admitted that racial profiling was a Cuban law enforcement policy.

Hamlet Lavastida. Unidad de Operaciones, DSE, G-2, MININT, Patrulla no. 955. 2020

While the physical location of the June 30 protest was under lockdown, the Internet was exploding with commentary about the killing of Hernandez-Galiano and the detentions being examples of excessive state force. Hernandez-Galiano had been fleeing police when he was shot in the back; the protesters, journalists, and activists who sought to gather peacefully were treated like threats to national security. Their own experiences of being unjustly targeted have led them to reconsider the routine practices of violence against cubanos de a pie (ordinary Cubans). According to Otero Alcántara, who is Black and self-taught, this recognition of injustice and increased willingness to take risks represent an important change of heart for the artistic and intellectual elite. “They are identifying with the suffering of a poor, marginalized and criminalized sector of the population…. Hansel was from a poor barrio and one would expect his own community to come out in support of him. But they don’t have a way of expressing their dissent. The mere fact that 100 people were willing to risk going to jail is a huge step. Racism is a very sensitive issue in Cuba—the government’s position is that racism doesn’t exist so there are no institutions to address its existence.”

Indeed, Cuban artists have largely steered clear of direct condemnations of racism in the post-revolutionary era. Instead, the prevailing tendency has been to focus on Afro-Cuban spirituality and popular culture. One exception that comes to mind is José Angel Vincench’s painting of the mug shot of a Black Cuban man from his 2008 series What History Did Not Tell You, an allusion to the infamous case of three men who were secretly tried and executed for hijacking a ferry in an attempt to escape the island in 2003. While the June 30 protest represents an unprecedented joint effort for artists and activists, Cubans are divided about recent Black Lives Matter protests in the US. Some are wary because they believe that the Cuban government has always exaggerated the extent of racism in the US as part of its ongoing anti-American propaganda campaign. Anti-Castro hardliners on the island and in Miami also resent that Black Lives Matter publicly expressed admiration for Fidel Castro upon his death in 2016. They see this as yet another example of foreigners’ unwillingness to recognize that the same Cuban government that sent soldiers to Angola and harbored Black activist fugitives from the US, also banned Afro-Cuban religions for 30 years, censored Afro-Cuban artists, and prohibited the establishment of Afro-Cuban political organizations.

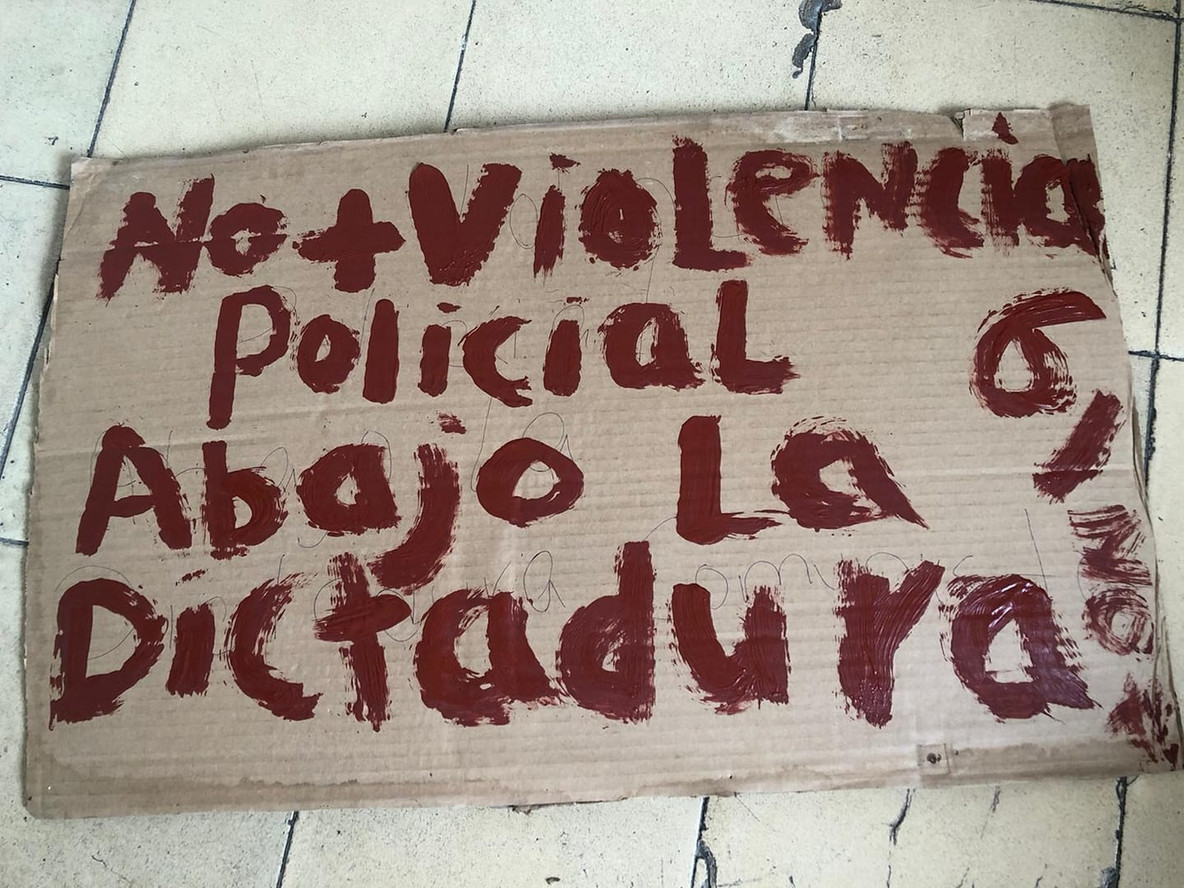

A protest sign treading, “No Police Violence, Down with Dictatorship, 6/20”

And then there are Cubans who consider themselves critical of their government but don’t take the artists’ efforts seriously. They see them as disorganized, unsuccessful, and representative of a societal fringe. It is not hard to understand why skepticism might prevail in a country with limited possibilities for political engagement, where harsh penalties are often imposed on those who think differently. But the artists involved in birthing a broad-based, participatory political culture take a more philosophical view. Their approach is similar to that of the artists in the US who recently took to sky writing to express their solidarity with undocumented people in detention: They believe that no single artwork will eradicate a political problem, but at the same time, no major social transformation can take place if we cannot come together to imagine a different world.

Related articles

-

Resources

Working for Black Trans Futures

An incomplete list of resources and organizations for combatting racism and transphobia, and supporting justice, safety, and equality

Jun 23, 2020

-

Magazine Podcast

Dignity Does Not Rest: An Interview with Tania Bruguera

The artist describes her 2018 arrest for protesting the Cuban government’s Decree 349, and why she plans to continue fighting.

Stuart Comer, Tania Bruguera, Leah Dickerman

Dec 14, 2018