What to Read: A Picture Is Worth 1,000 Words

MoMA’s Department of Photography shares favorite catalogues, novels, artist’s books, and memoirs about the camera.

Apr 21, 2020

At a time of travel restrictions imposed by the global pandemic crisis, Teju Cole’s Blind Spot (2017)—a collection of 150 richly colored photographs from five continents—offers immeasurable pleasures. Conceived after he suffered an attack of papillophlebitis, or “big blind spot syndrome,” the book tests the limits of vision. Each picture is paired with a short, evocative text. While the texts lack a direct relation to the pictures, the space in between elicits endless associations. An image of sheer white curtains in a Nuremberg hotel is linked to a consideration of Albrecht Dürer’s drapery studies; a picture of Beirut balconies accompanies a discussion of Emily Dickinson’s poetry. Cole’s literary eye has produced a new genre—the experimental multimedia travelogue novel. An imaginative cultural journey!

—Roxana Marcoci, Senior Curator

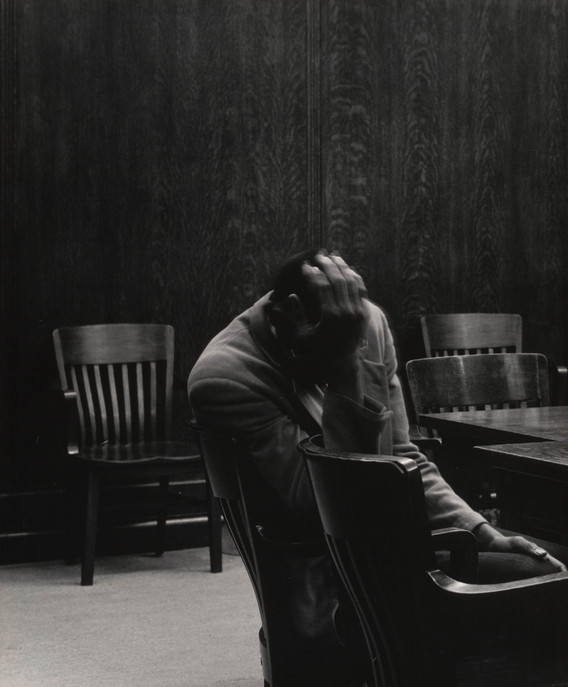

Not so long ago, MoMA published a small book about Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, which started me thinking about the ways in which words and pictures intersected throughout Lange’s remarkable career. Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures is the result, and it includes new contributions from 12 creative thinkers reflecting on Lange’s significance today. One of these is Sally Mann, who wrote about this photograph: “We die of the piercing shaft of wall-panel joinery that plunges straight into the bowed head. The unsparing seat of the wooden chairs, with their jail-cell vertical elements. The poignancy of the pressed hand. We are dying of the grief we share with all too many defendants, the helplessness and desolation on the other side of silence.” Mann’s achievements with a camera are widely recognized, but I would argue her talent with words was somewhat overlooked until she published Hold Still: A Memoir with Photographs (2015), an irresistible meditation on the medium intertwined with an unforgettable biography.

—Sarah Meister, Curator

Dorothea Lange. The Defendant, Alameda County Courthouse, California. 1955–57

Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life is my favorite novel; I recommend it any and every chance I get. It’s an impeccable and deeply moving story about four college classmates who start their careers in NYC. The love, cruelty, and trauma that they face throughout their enduring, decades-long friendship will have you fully immersed. In a Vulture article, “How I Wrote My Novel: Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life,” the author explains how photographs influence her fiction: “I began collecting photography when I was 26...and when I actually began writing, it was these images I returned to, again and again: They provided a sort of tonal sound check, as it were—was I conveying in words and scenes what I felt when I saw these photographs and paintings?” This relationship explains how Yanagihara selected a cover image that captures the emotional essence of the book. Though her editor vehemently disagreed with her choice, Yanagihara fought, and won, to use a portrait by photographer Peter Hujar. It is a mesmerizing image that ambiguously depicts either great pain or pleasure, an intense dichotomy that readers come to understand as central to Yanagihara’s sweeping narrative.

—Jane Pierce, Carl Jacobs Foundation Research Assistant

Carmen Winant. My Birth. 2018

“Is it possible to leave everything behind?” So begins Carmen Winant’s text in her 2019 book Notes on Fundamental Joy; seeking the elimination of oppression through the social and political transformation of the patriarchy that otherwise threatens to bury us. “Is it possible to begin again, outside of and beyond every system of living that you’ve ever known, reinventing what it means (and looks like) to exist, as a body and its soul, on the land?” Winant—whose immersive installation My Birth is in MoMA’s collection—here brings together photographs by JEB, Tee Corinne, Clytia Fuller, Ruth Mountaingrove, and others who participated in lesbian and feminist back-to-the-land movements of the 1980s. Their separation came out of very different circumstances than our current ones as we abandon our “normal” routines and isolate ourselves at home. Yet the strength and imagination of the women whose images and stories are chronicled in these pages, as they found new meaning and possibility in a life outside mainstream patriarchal society, is heartening.

—Lucy Gallun, Associate Curator

In this time of heightened constraint and restriction, I’ve found some assurance in the work of Eileen Quinlan and the way in which her photographs and sensitive use of language offer models for alternative forms of encounter. Quinlan probes the surfaces of photographic images, exploiting their susceptibility to scratching, melting, and tearing. As much haptic as optical, her photographs reveal and dissolve resemblance through a strategy that she calls “conjuring.” Spirit photography was an important early influence on her thinking, and the gambit of Always Starts with an Encounter: Wols—Eileen Quinlan (2019) and the corresponding exhibition is to forge a dialogue between two artists who were never alive at the same time. In an interview with writer Quinn Latimer in the book, Quinlan describes her affinity with Wols, noting that most of his photographic work of the 1930s was made indoors, in a time of geopolitical crisis and personal psychological distress. “Through an altered state he saw his shrinking world in striking ways,” she observes. “Motherhood is another kind of trip. I relate to his compulsion to continue working, even with these limits of mobility. It’s a compulsion.”

—Phil Taylor, Curatorial Assistant

Eileen Quinlan. Brooks Brother. 2013

Lisette Model. Fashion Show, Hotel Pierre. 1943

Helen Gee’s memoir Limelight: A Greenwich Village Photography Gallery and Coffeehouse in the Fifties is an entertaining take on the history of photography. A true champion of the medium, Gee ran Limelight, the first commercial gallery dedicated exclusively to photography, from 1954 tp 1961. Her tales of struggle and success reveal a tenacious woman with incredible foresight for the value of photographs in the art market. Set against the unique landscape of 1950s Greenwich Village in New York City, Gee’s stories don’t hold back on gossip about the notable artist circles of the time. Her discussion of tensions with Lisette Model, and an unforgettable scene with Edward Steichen in a Kimono, are two highlights. Given its humorous and accessible tone, if I were to compare this memoir to TV, I’d say it’s more Bravo than Criterion Collection—and I’d argue that sometimes that’s the perfect thing.

—Tasha Lutek, Collection Specialist

W. G. Sebald’s The Emigrants takes readers on a transatlantic journey—from the schoolhouses of Germany to the markets of Jerusalem—engaging memory, trauma, and generational encounters across four tales. The photographs printed within—either originals or rephotographed from newspapers, family albums, and archives, although Sebald refused any easy interpretations of his sources—punctuate The Emigrants with a dual sense of mystery and authenticity, recalling many concerns of contemporary photographers and theorists such as Sophie Calle and Susan Sontag. Sebald’s singular voice winds throughout, eluding absolutes and carefully layering narratives until a grand picture of a postwar era comes into focus. If anything, read this while stuck at home. It will serve as a worthwhile reminder that there is a wider world out there.

—Eli Cohen, Intern

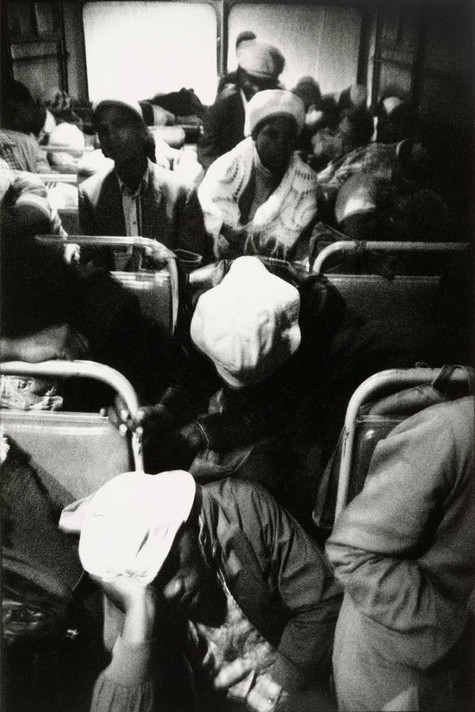

David Goldblatt spent 60 years with his camera trained on South African society, even (especially) when what he saw horrified him. The first half of his long career was spent in a nation under apartheid, in which Black Africans were brutally oppressed by a white minority. “The injustice,” Goldblatt recalled in a 2018 interview, “used to gnaw at me.” Many South African photographers with similar feelings produced iconic images of protests or violent clashes between resistors and government forces, but Goldblatt took a different approach. His work focuses on everyday life—on the way it can, and must, continue, even in the face of intolerable situations. The power of Goldblatt’s method was never more clear than in his 1989 book The Transported of KwaNdebele: A South African Odyssey, which was recently reprinted by Steidl. The photographs document grueling hours-long commutes endured by Black workers who had been forced to live in remote “Homelands” with few opportunities. Their exhaustion is clear, but so is their resilience and determination to endure.

—Benjamin Clifford, 12 Month Intern

David Goldblatt. The Transported of Kwa Ndebele: Going to Work – 3:30am Wolwekraal-Marabastad Bus, Standing Passengers Have Slumped to the Floor. 1983

Related articles

-

Building Worlds: Movie Recommendations from MoMA’s Department of Architecture and Design

From Jacques Tati to Clueless, they’ve shared a bevy of films in which architecture and design are the stars.

Apr 1, 2020

-

For families

Favorite Children’s Books about Art

From childhood favorites to parents’ picks for toddlers or teens, Museum staff share beloved art-themed kid’s books.

Elizabeth Margulies

Mar 26, 2020