Remembering Robert Frank, 1924–2019

MoMA curators pay tribute to an artist who changed the way we see.

Robert Frank. Funeral, Paris. 1951

In November 1952, Robert Frank gave a handmade book of his photographs to Edward Steichen, who was then director of MoMA’s Department of Photography. The spiral-bound, nearly square album has an austere black cover bearing only Frank’s name and the words “BLACK WHITE AND THINGS” in an emphatic white font. It is one of three identical copies, except for this inscription: “With much respect/and gratitude/to Mr. Steichen/R. Frank./Paris, Novembre 1952.” The 34 gelatin silver prints are arranged in sections that correspond with the album’s title, whose simplicity belies the expansive range of meaning it encompasses. Frank celebrated his 28th birthday that month; years would pass before he would find a publisher for The Americans, then turn away from still photography to film, and then turn back to challenge the basic tenets of the medium, often with hauntingly personal pictures. These are the three exceptional bodies of work on which his reputation rightly rests, and yet, before all this, he was already an artist of the highest order.

Frank photographed many funerals, but this one, the 11th image from Black White and Things, has always been my favorite. The sweep of rain-kissed umbrellas reads like the mark of an Expressionist painter: Frank’s attentiveness to contemporary painting is in ample evidence across the album, but at heart he was a photographer. Who else could create an image dark enough to instantiate the mourners' grief, blurred enough to suggest the trembling, reluctant determination of their procession, and luminous enough to leave us with a sense of hope we so desperately need?

Sarah Meister is a curator in the Department of Photography.

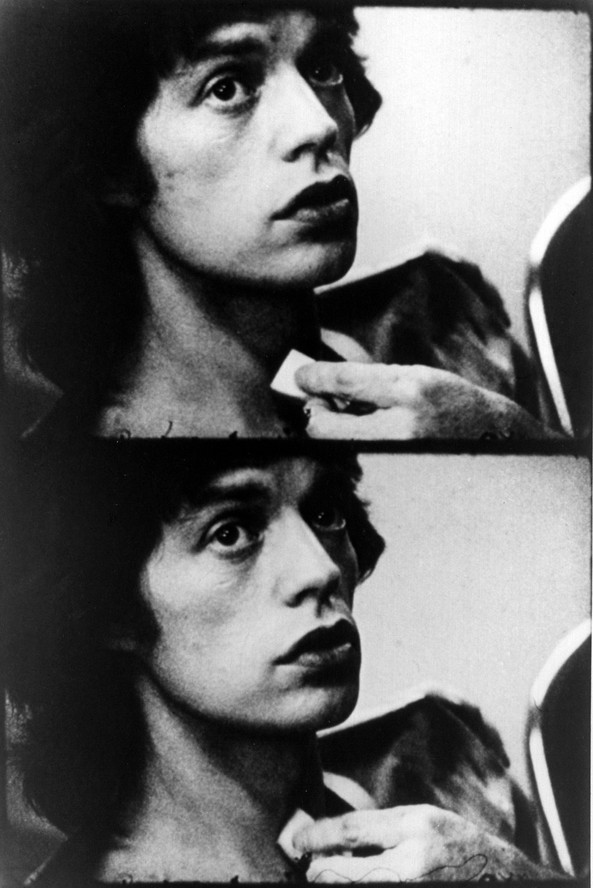

Mick Jagger in Cocksucker Blues. 1972. Directed by Robert Frank

The Museum of Modern Art’s relationship with Robert Frank goes back more than a half century. One of the most influential artists in the history of photography, Frank received his first museum exposure in Edward Steichen’s 1950 MoMA group show Photographs by 51 Photographers. In 1961, he and Harry Callahan were the subjects of a joint retrospective at the Museum. Since then, MoMA has become a major repository of his photographs. Recognizing this uniquely important relationship with MoMA, Frank and his foundation, The Andrea Frank Trust, donated all his unique film materials in 2017. These pre-print and print elements span the entirety of Frank’s film career, from his 1959 Beat psychodrama Pull My Daisy (codirected by Alfred Leslie and starring the poets Allen Ginsburg, Peter Orlovsky, and Gregory Corso; the artists Larry Rivers and Alice Neel; and the actress Delphine Seyrig; with narration by Jack Kerouac) to his 2008 Fernando, a touching portrait of a Swiss artist friend.

No mere handmaiden to his photography, Robert Frank’s films have profoundly altered his approach to making images. Out of restlessness and a passion for experimental risk taking, Frank abandoned photography for filmmaking in the late 1950s. When he returned to still photography in the early 1970s, his work had become less precious and singular. Instead, he subjected his still images to a variety of manipulations: scratching and painting directly on the negative or emulsion surface, collaging and creating montages. The photographs began to resemble film sequences or storyboards: multiple frames of images with implied narratives and use of written texts as commentary. Films like Conversations in Vermont (1969) and About Me: A Musical (1971), autobiographical portraits of family life and community, were direct antecedents to deeply personal, intimate projects like his 1972 artist book The Lines of My Hand. And the films’ seemingly improvisational quality led to an interest in the immediate gratifications of Polaroids.

After seeing these pictures you end up finally not knowing any more whether a jukebox is sadder than a coffin.

Jack Kerouac

Robert Frank’s films include The Sin of Jesus, his 1961 adaptation of an Isaac Babel short story; OK End Here (1963), an intimate chamber piece featuring an original score by the great free jazz composer and musician Ornette Coleman; and Me and My Brother (1965–68), his first feature, a faux vérité involving Allen Ginsburg, Joseph Chaiken (founder of the off-Broadway Open Theater company), Peter Orlovsky, and his catatonic schizophrenic brother Julius. They are an important documentary record of bohemian artist life in 1950s and ’60s New York; tender portraits of friends (Danny Seymour, the Chinese artist Sanyu, the newspaper deliveryman in his rural second hometown of Mabou, Nova Scotia); painfully raw confrontations with the personal tragedies of his daughter’s accidental death and his son’s mental illness; diaristic travelogues; and thoughtful interrogations of the artist’s own divided loyalties between work and family.

Frank’s interest in the malleability of truth, in setting up conditions for improvisation within a scripted or premeditated framework, is perhaps best exemplified by his end-of-the-road movie Candy Mountain (1987), a collaboration with the novelist Rudy Wurlitzer, and his notorious Cocksucker Blues (1972). “After seeing these pictures you end up finally not knowing any more whether a jukebox is sadder than a coffin,” Jack Kerouac wrote in his introduction to Robert Frank’s landmark 1958 photographic essay The Americans.

Josh Siegel is a curator in the Department of Film.

Robert Frank. Trolley—New Orleans. 1955

In 2012, I presented Robert Frank’s Trolley—New Orleans (1955) in The Shaping of New Visions: Photography, Film, Photobook, an exhibition at MoMA exploring the intersections of unconventional still and moving images, ranging from photograms and photomontages to experimental films and photo books. Frank’s picture, photographed only weeks before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, offered a blistering view of segregated America and the indignity of racial injustice during the Eisenhower era. Not only was the picture included in his touchstone photographic essay The Americans (1958), but it became the cover of the book’s early editions.

Frank, who befriended Walker Evans in 1953, patterned The Americans on the structure of the older photographer’s book American Photographs (1938), but Frank’s elliptical, off-kilter style was as personal and controversial as was his innovative treatment of his subject matter to reveal a profound sense of alienation in American life. The Americans is the corollary of a journey Frank made across the United States, with the help of a Guggenheim grant, in 1955 and 1956. The book was first published in France in 1958, as Les Américains. The American edition, with an introduction by the Beat writer Jack Kerouac, came out the following year. During his road trip, Frank had taken 800 rolls of film, snapshot style, but only 83 frames made the final cut of the book, each carefully orchestrated into a tight sequence, as in a film script.

His skeptical, outsider’s view of postwar American society, best exemplified in Trolley—New Orleans, earned him comparisons to a modern day Alexis de Tocqueville, the 19th-century French author of Democracy in America (published in two volumes, in 1835 and 1840). Frank’s picture captures a shadowy postwar society at odds with itself, and inaugurates a turn to a deadpan documentary style that galvanized a new generation of younger artists. Among them, Ed Ruscha perhaps best summarized the power of Frank’s inspiration: “Seeing THE AMERICANS in a college bookshop was a stunning, ground-trembling experience for me. But I realized this man’s achievement could not be mined or imitated in any way, because he had already done it, sewn it up and gone home. What I was left with was the vapors of his talent. I had to make my own kind of art. But wow! THE AMERICANS!”

Roxana Marcoci is a senior curator in the Department of Photography.

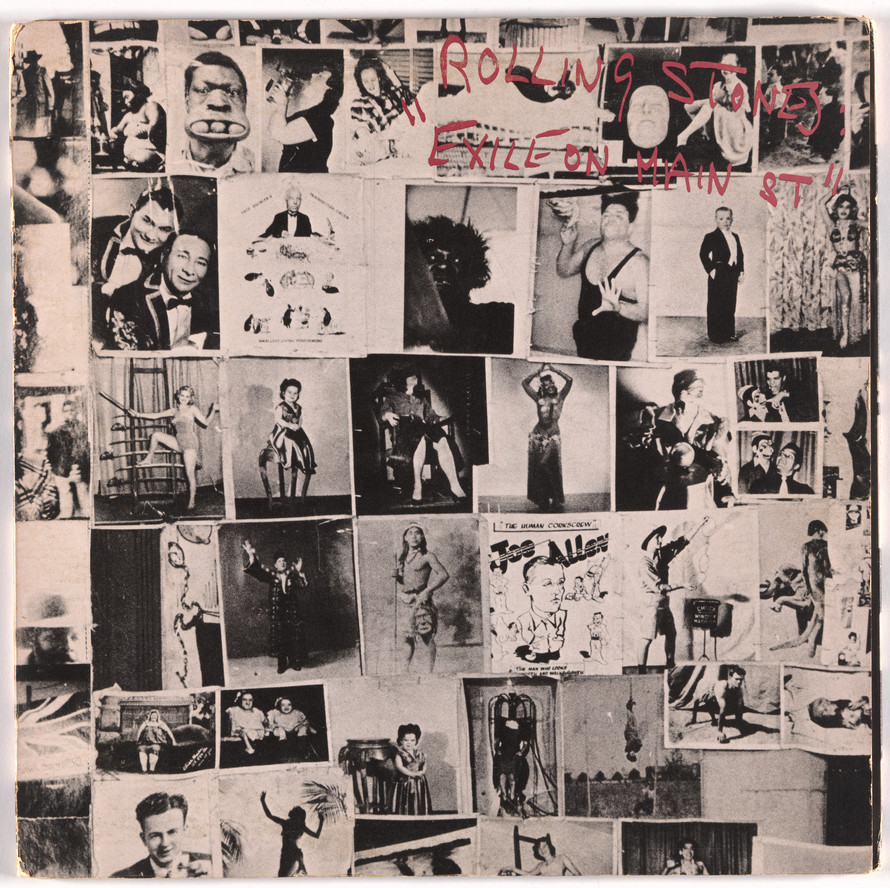

Robert Frank. Album cover for The Rolling Stones, Exile on Main St. 1972.

Cocksucker Blues is an exceptional document capturing the malaise of the early 1970s. Joining the Maysles Brothers’ Gimme Shelter (1969) and Jean-Luc Godard’s Sympathy for the Devil (One Plus One) (1968), Robert Frank’s most elusive film takes The Rolling Stones as its subject, meandering through flickers of 1960s rock ‘n’ roll liberation and the darker, more degraded hangover that followed the violence at the Stones’ Altamont concert in 1969.

Frank opted not to fix a light leak in his camera magazine while he was shooting, imparting a blue haze to the band’s decadent twilight world and suggesting Frank’s uniquely impromptu, gritty approach to the cinema vérité techniques of the time. Seeking to shift public perception of the band following the Altamont controversy, the Stones enlisted Frank, whose work also graces the cover of the band’s album Exile on Main Street, to capture their return to glory.

That plan unraveled quickly. If Frank’s photographs helped to herald the “snapshot” aesthetic in photography, Cocksucker Blues is less a frozen moment than a slow burn of drug use, inflight orgies, and pockets of deep ennui between dazzling moments onstage. The Stones blocked the film’s release, and to this day legal agreements have severely limited screenings of the film to very rare occasions involving a heavily edited version shown usually in the context of a major Frank exhibition. Consequently, the film is known primarily through rumor.

At the heart of the mythology that has replaced firsthand encounters of the film are the groupies. Their allegedly debauched encounters suggest a drug-induced submission to the band and the epic revelry of their traveling circus. What’s often overlooked, however, are moments in which women command the frame: Bianca Jagger poised attentively over a music box, or flaunting a new dress during a fitting with the legendary designer Ossie Clark; Tina Turner outshining an animated group of friends accompanying Truman Capote backstage, including Andy Warhol and Lee Radziwill. The particular charge created by these women onscreen suggests a slightly different narrative than that commonly projected on the film, and one in keeping with a great talent of Frank’s: candidly juxtaposing the powerful and the marginalized and opening up a clearer vision of an American society rooted in paradox.

Stuart Comer is the Lonti Ebers Chief Curator of Media and Performance.

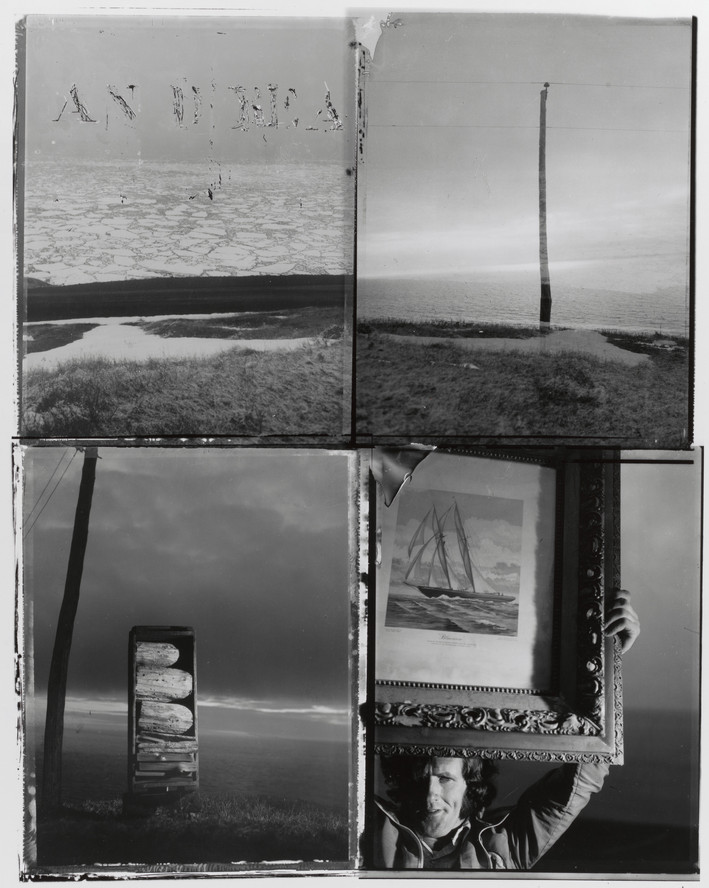

Robert Frank. Andrea, Mabou. 1976–78

Photographs have served as keepsakes or mementos of absent individuals since the earliest days of the medium. Who understood the power and potential of photography’s memorial evocation better than Robert Frank?

Frank’s own life was marked by multiple great tragedies—foremost among them the untimely deaths of both his children, Pablo and Andrea—the impact and reverberations of which continuously shaped his life and his work, as traumas do. Following a hiatus in which he focused primarily on film, Frank had returned to still photography in the 1970s, shortly after purchasing a home in Mabou, on Cape Breton Island, with his partner, the artist June Leaf. Before Andrea’s death in a plane crash in Guatemala in 1974, at the age of 21, she had lived with her father and June at this home in Mabou, and their meaningful time together there allowed Frank to hold that place as one where he could feel and position her memory. Instead of grave markers, Frank utilized other symbols in the landscape: the fence posts, timber pilings, and telephone utility poles that stretched down the cliffs from their home to the ocean became motifs that appear again and again in his photographs.

In a series of photographic montages—some incorporating Andrea’s name through stencils or handwritten text, others purely image-based—Frank memorialized his daughter through these found monuments pictured against the sea, and in his film Life Dances On, completed in 1980, Frank juxtaposed images of Andrea herself with footage of the sublime Mabou landscape.

In 1985, Frank reflected, “I have a lot in back of me and that’s a tremendous pull, of what has happened in my life, backward. And in front of me I have the sea.” The tides come in and out; the sea washes away, but it also replenishes.

Lucy Gallun is an associate curator in the Department of Photography.

Related articles

-

Tribute

Remembering César Pelli, 1926–2019

MoMA reflects on the legacy of the architect who designed the Museum Tower.

Peter Reed, Martino Stierli, Glenn D. Lowry

Jul 30, 2019

-

Magazine Podcast

Dream Life: A Tribute to Agnès Varda (1928–2019)

Two admirers discuss Agnès Varda’s gift for human connection.

Rajendra Roy, Natasha Giliberti

Jul 3, 2019