Reynaldo Rivera’s Fistful of Love/También la belleza

The artist talks about learning to freeze fleeting moments, the influence of music and movies, and how his life’s work is also a search for love.

Reynaldo Rivera, Lauren Mackler, Kari Rittenbach

Jun 18, 2024

Reynaldo Rivera’s work has immortalized the colorful figures circling through his orbit since the early 1980s, when he first began using his camera to record their dreams and desires. His photography refutes the medium’s specious objectivity, reflecting the atmosphere of the surrounding environment by making use of available light—both natural and artificial—as well as shadow.

Rivera’s first solo museum exhibition, Fistful of Love/También la belleza, on view at MoMA PS1 through September 9, includes never-before-seen photographs from the artist’s archive, alongside a film newly edited from Hi8 footage. Rivera’s photographs—which are included in MoMA’s collection—are informed by the drama and deep emotion of boleros and rancheras, the glamor of Old Hollywood and the Golden Age of Mexican cinema, and earlier trailblazers in photography like Nadar, Brassaï and Henri Cartier-Bresson. Rivera joined guest curator Lauren Mackler and MoMA PS1 assistant curator Kari Rittenbach to discuss the exhibition, revealing the stories behind some of his subjects (often friends or lovers), what it means to publicly exhibit his very personal “blue” series, and the experience of looking back on the past three decades of his work.

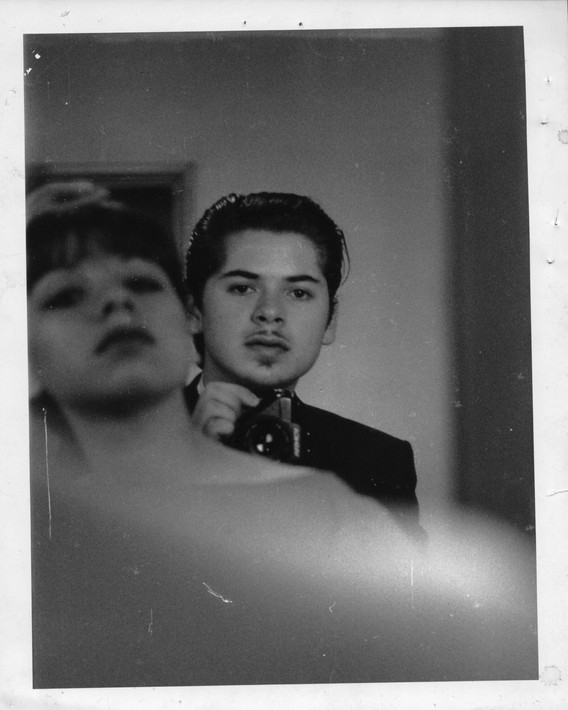

Reynaldo Rivera. Martine (Herminia) and Reynaldo Rivera. 1981

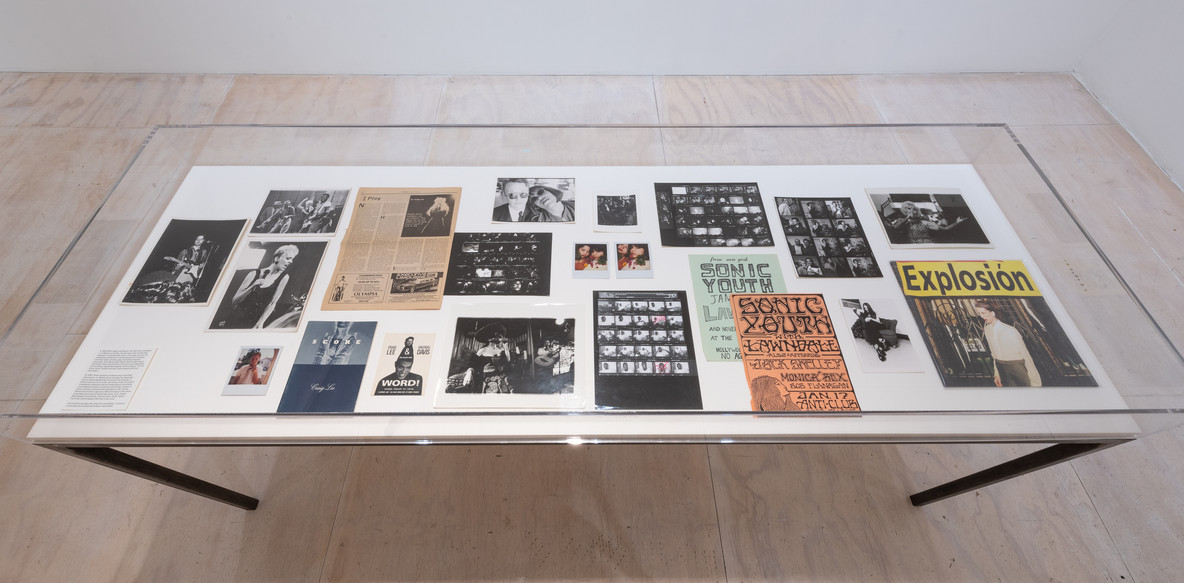

Installation view of Reynaldo Rivera: Fistful of Love/También la belleza

My life was constant movement, and photography allowed me to freeze certain moments.

Reynaldo Rivera

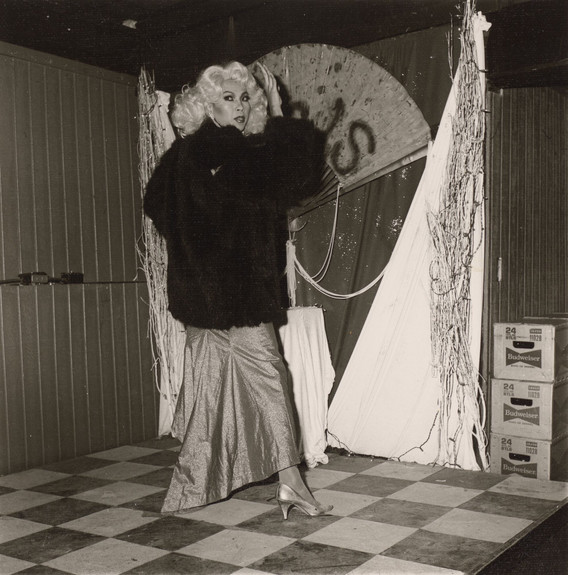

Reynaldo Rivera. Performer, Mugy’s (1). c. 1990

Kari Rittenbach: How did you first begin to approach photography?

Reynaldo Rivera: Let’s start in the beginning. I got this camera, a Yashica, from my dad. We both worked picking stuff and also in the canneries. We were harvesting cherries, tomatoes, cucumbers, whatever was in season between July and September. We were migrant workers, which took us to Stockton, California.

Kodak invented the Instant camera to make photography accessible to the common man, apparently. But even that was expensive, and most people didn’t have the money to buy those cameras. A certain level of people could not afford those things. And that was my level.

I didn’t grow up with family photo albums—photography was not something that happened in our family from way back. As a child in Mexico, people would sit around in the kitchen during Christmas and birthdays and just talk about people in the family. We would remember. They would begin with the oldest, Bonefacia, my great-great-grandmother. And then my grandmother, and what happened on what date. By the end of the evening, I had a full story of the family—basically an oral history instead of a photo album.

Twenty years later, I bought my first camera from my dad. It happens to be in the very first photo of this exhibition. And in a way, I continued this tradition; preserving moments that I probably wouldn’t remember otherwise. My life was constant movement, and photography allowed me to freeze certain moments. This photograph is a reflection of me and my sister. How old was I?

Lauren Mackler: This is from 1981; you were 17.

Shit, I was young. At this time, I was still heterosexual in my mind. I was in the closet, just very deep in there. I was listening to punk rock and some music my sister introduced me to, which is really what caused the change. The music. I started dating a guy who worked as a music critic at the LA Weekly, Craig Lee. Because of this, I was able to photograph whoever I wanted. We also went to see Sonic Youth; their first tour.

Reynaldo Rivera: Fistful of Love/También la belleza

LM: I think of your early music photography as the beginning of your learning how to capture performers performing or people under a spotlight on stage. It feels like it informs your later work in clubs. Do you think about it that way?

No, but thank you for asking this question. This all happened at a time that I was learning as I was going. When I first picked up the camera, I had no clue. It was a box, a metal thing with a lens. I just started clicking the shutter. Every roll would come out blank! Photography has always been costly. Film was expensive. Developing was expensive. But I had started working at a cannery, which paid well for the time ($8 an hour and we worked seven days a week), so I could afford to buy film. I was just throwing away roll after roll—it was depressing. I started asking the lady who worked at Photomat what was going on, and she was the one who taught me by trial and error. Each time I turned up with something that didn’t come out, she basically showed me what every single dial on the camera was: first the shutter speed, then the F-stop, and so on. And then all of a sudden, shit started coming out. It was like magic, like alchemy.

A few years later, when I started doing photos of bands, there was all this weird lighting, background lighting. It either worked or didn’t work. I learned just by doing and having an eye. Of course, an eye is something you have to develop, but you should already have an idea of what you like. That’s where artists differ from one another—in how you view the world. I view the world this way, I think, because of the music I listened to when I was a child, when I was exposed to Toña la Negra and Billie Holiday. These singers are constantly suffering, but the music comes from very emotional folk who deal with things their own way. For me, it created a desire to see things a certain way. Then there were the silent movies I was exposed to as a young teenager. These influences never left; you can still see traces of the lighting.

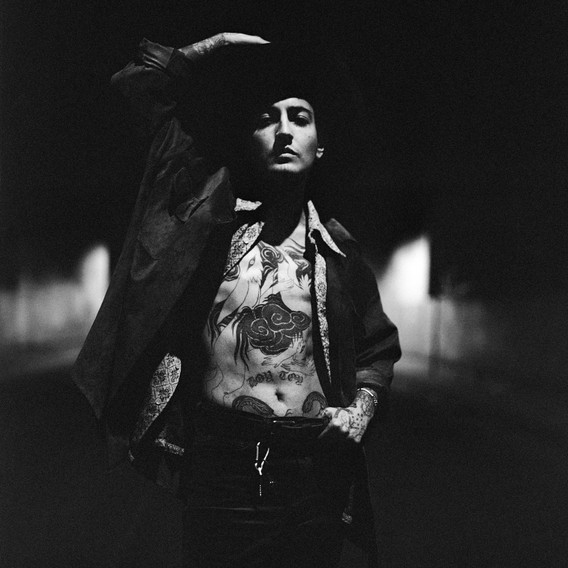

Reynaldo Rivera. Coyote, Downtown Los Angeles. 2022/2024

I’m a homo who documented his own world. And my world’s already coded, especially the world in the mid-1980s.

Reynaldo Rivera

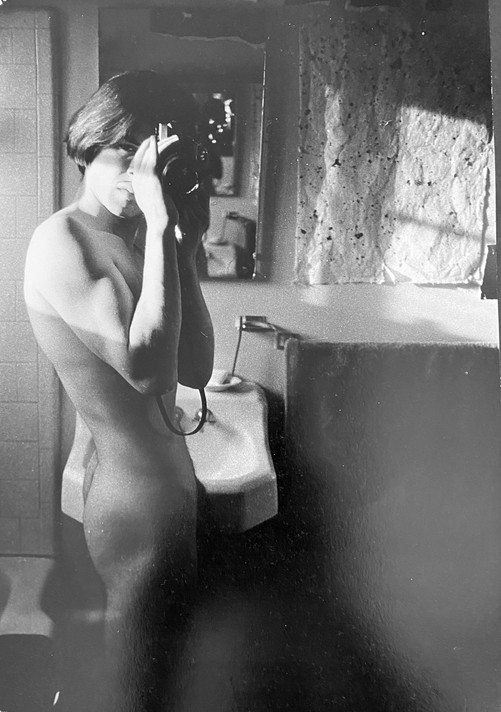

Reynaldo Rivera. Self-portrait, Pasadena. 1985/1990

KR: Aesthetically, film history has been an important reference for your work—especially silent movies and film noir. Where and how did you first encounter cinema?

I used to ditch school a lot and watch movies at 12 o’clock. There was a show called Hollywood Presents, with some old guy who talked about movies. The year I started watching, they were showing the filmography of all these different actors: Gene Harlow, Marlene Dietrich, Greta Garbo. I became a fanatic, a true fan. This was before I bought the camera. I saw Blonde Venus (1932) and Shanghai Express (1932). Actually, my favorite silent movie is King Vidor’s The Crowd (1928). These movies really left an impact, as they have a very special lighting, which I believe cities also have. And then there’s Los Angeles—we’re the film noir capital of the world.

At one point I started going to Pasadena City College with my sister—I went along to her film class, because they would show movies for free. And we met all of these young people studying there at the time, who became friends. In the PCC class they screened silent movies like Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927)—a kind of documentary film telling the story of the city indirectly, through the people who lived there. I’ve always wanted to make a movie about LA in that way. A few years ago I found a place like this in the old Garment District in LA. I was doing photos for a gallery show, and I have to admit, I didn’t see it at first. When I developed and printed the work, I recognized the old LA: That alley in Kiss Me Deadly (1955) and Touch of Evil (1958), that alley of the long shadows which is gone because of a political need for safety. But you can’t have safety and liberty at the same time.

With photography, you’re showing the public the world through your eyes. If you really look closely at the image, if you pay attention to the little things, you can tell a lot about the person who took the photograph. I’m a homo who documented his own world. And my world’s already coded, especially the world in the mid-1980s. You could say I was decoding my environment for other people like myself, originally. My work was intended for me, my viewing pleasure, and my friends—the people in the photos. The exception was what I would do for the newspaper. But often, that was someone I liked or admired—one of us. And I don’t mean just queer. I mean people like us; we know who we are.

This is a pretty rare photograph. I had an issue with nudity—being a Mexican and a Catholic. I actually hated to see myself in the mirror. I still do. So, this was not a very common thing. When I was younger, we went to the beach with clothes on. It was a long time before I printed nudes of myself. I’m 18 here.

LM: This is a photograph from your “blue series” that was developed relatively early, while the others in the exhibition are images/negatives you only returned to last year.

That was another thing. These images were taken in the 1980s and never developed. The film stayed in a bag for years. Then one day, I think maybe in 1990, I found this bag with all these rolls and I developed it. This stuff was in it. I think I had issues with the subject matter. So yeah, I printed the image long after I took the photos.

LM: Let’s discuss the Polaroids and your early fashion shoots.

Polaroids are instant gratification. This is the jerk-off of photography. You did not have to think too much. Just take the fucking photo, right? I made a Polaroid because I couldn’t afford to make color prints. A friend of mine had a Polaroid camera. But it was expensive—one dollar per photo at the time. If anything, my work is about the moment—moments that I cared for. In that way, the Polaroids are extra charged. I used to have a lot of my photographs hanging in my house. You can see them in the background of some images: older photographs hanging on the wall. But then, there was a moment when they were too much. In 1999, everything came down, to be packed away forever, and for a long time, I couldn’t look at this stuff because of nostalgia. Photography is all nostalgia. So, if you happen to be a gal who suffers from melancholia, then photography is not your thing. So, for the longest time, I put all this stuff away. I couldn’t even look at it. So many people have gone.

Some of the really early polaroids were taken in 1982, and some are much later; they span four years, so they cover very different times in my life and different levels of craziness. It was a really wild time. It’s hard for me to put it into words. I really burned the candle at all ends. It’s funny because I used to have this regret that I didn’t do enough. I felt like I should have done more. That’s always my advice to young people. Don’t leave it for the golden years. When you’re young, everything’s new. It’s first-time stuff that has a huge impact on your life; you’re creating a story.

And this is my older sister: Martine Herminia Rivera para servirles. She and I were kidnapped when we were children, taken to Mexico, and left in some village in the middle of nowhere. She was my savior, my protector, she was everything to me. She’s still here, and still as tough as ever. Martine was the one who would sew all the clothes, and I would photograph—we would create all of these fake fashion trends together. Is there another word for it?

LM: Improvised?

Well, they were fake in the sense that they were not real fashion trends that were happening. We would invent these trends that she would sew up. My friend at the Weekly was a fashion editor. She would write the story and then publish it. These were the Cha-Cha Girls. “Las Cha-Chas.” But there were real Cha-Chas, by the way. I took the name from real stuff. They were these girls, these cholas, these Latina girls who used to call themselves Cha-Cha, so I just threw in the girl part: the Cha-Cha Girls. Boom. We would create something that became real. But we made it up. Drag is that way too. It’s about the fantasy, the allure.

Reynaldo Rivera: Fistful of Love/También la belleza

LM: Can you tell us the story of Mrs. Alex and how you started photographing in clubs?

It was 1992. A friend from Mexico City, Armando Cristeto, was visiting, and I took him to see a show at the Silver Lake Lounge. Mrs. Alex came on stage, and he got this look of excitement and said, “Oh my God, do you know who this is?” She was a mega star in the Mexico City underworld. She left Mexico because she fell in love with a muscle guy, one of those bodybuilder dudes. She followed him to Los Angeles, for love. And, of course, he dumped her in California. She crossed the border with a coyote and the whole thing. People cross borders for many reasons, not just to work in the fields. She crossed for love, and then love did her wrong. The story was intriguing. I introduced myself to her, and we hit it off. She came back to my place, I interviewed her that evening and took her picture.

Reynaldo Rivera. Miss Alex, Echo Park. 1992

One day, I was at La Plaza taking photos of Frau Alex, and she said, “I want you to take some photos of me in the dressing room, getting dressed.” So I went to the dressing room. Of course, all the girls were side-eyeing like, “Really, bitch?” But Alex was the queen, she said “Come in,” so I went in, and I started taking photos. When I came back and showed her the photos, all the other girls were like, “Ooh, we want some photos too.” To me, all this stuff was super exciting, and I love their work. Of course, I came at this from love; you can see it in the images.

Reynaldo Rivera. Paquita and Reynaldo Rivera, Le Bar. 1997/2021

KR: What was the art context in Los Angeles like when you first started showing in galleries?

I wasn’t really big on art for art’s sake. During my youth, it seemed that if something wasn’t created in a studio, it wasn’t art. And, mind you, I didn’t go to school for any of this, or any kind of school, really. For that reason, I also wasn’t considered for anything, because, in those days, if you didn’t come from those places, like institutions of education or art school, you weren’t that. So, I never viewed myself as an artist. I couldn’t even imagine it—but not because I didn’t want to be an artist.

I didn’t have the patience or the tools to deal with the art world then. And I was conscious of not having credentials.

LM: Tell us about the double title, Fistful of Love/También la belleza.

Love hurts. I was all about love since I was a child when I truly believed that love would save me. I mean, I grew up in misery, so I really thought that one day love would show up, and it would be that one person, and we would ride into the sunset and la la la. But, fuck, it hasn’t happened. So, at 60, I can honestly say love isn’t the answer. It’s the question. It’s also like a vaccine: a little piece of the disease that you have to overcome. And so the reason I picked Fistful of Love is because love is a fucking fist. I am just saying.

The first half of the title comes from a song that I heard by Anthony and the Johnsons. And it begins, “We live together in a photograph of time.” And the other half of the title is a song called “También la belleza,” by Liliana Felipe. She’s one of my favorite composers, musicians, singers. I used to sing that song to my man because he was gorgeous, but she was dirty. She just left a mess everywhere. The song is about beauty and how beauty decays—even beautiful flowers fade and leave a stinking mess. And that’s like love. It decays, and then it leaves a stinking mess.

Almost everyone in the exhibition is young. I just thought of that. All the youth. And it goes by really fast. It’s like you’re young for such a short time and then you’re old for the rest of your life.

LM: One remarkable aspect of this exhibition is that while your work is deeply subjective (it’s your life, your people and places, your scene) it has tendrils into (and collides with) larger social histories and scenes (LA in the 1990s, the AIDS epidemic, music, fashion, queer clubs, literary and art worlds). You are capturing your life, but you end up capturing all these other things around you.

Well, you know, living is history. Every minute becomes history. I just happened to be in all these places when certain things happened. I was in Berlin when the wall came down, in Mexico City when the city fell in 1985, in September. And I was a queer child that unfortunately happened to come of age right at the dawn of the AIDS epidemic, so I came of age during a time when sex was death, being gay was death.

Coming up gay, being Latino, poor, I feel that it put me in this trajectory. It wasn’t a common thing for kids from where I was coming from to be in these kinds of scenarios, to hang out with Annie Lennox or have dinner with Mark E. Smith from The Fall. I was a hustler on top of that. I had a good hustle.

You mentioned the backdrop of the Rodney King riots in one scene of my movie, the stores boarded up. It was just the way I was experiencing something happening to the city, to the neighborhood, to the places that I inhabited. And, yes, obviously that was the main storyline, but I was always paying attention to the other story, the story that didn’t matter at the time, or that doesn’t get recorded.

Fistful of Love/También la belleza is on view at MoMA PS1 through September 9, 2024.

Related articles

-

Hyundai Card First Look

Martine Gutierrez

Learn about four self-portraits from the artist’s Indigenous Woman project that have recently joined MoMA’s collection.

Caitlin Ryan

May 30, 2024

-

What to Do When the World’s on Fire: A Conversation with Catherine Opie

The acclaimed artist talks about the photograph that made her a photographer, her philosophy around portraiture, and queer liberation.

Catherine Opie

May 22, 2024