Word Play: Poems Inspired by Ed Ruscha

Acclaimed poets Rae Armantrout and Mónica de la Torre are inspired by the irregular verbs of great art.

Rae Armantrout, Mónica de la Torre

Jan 5, 2024

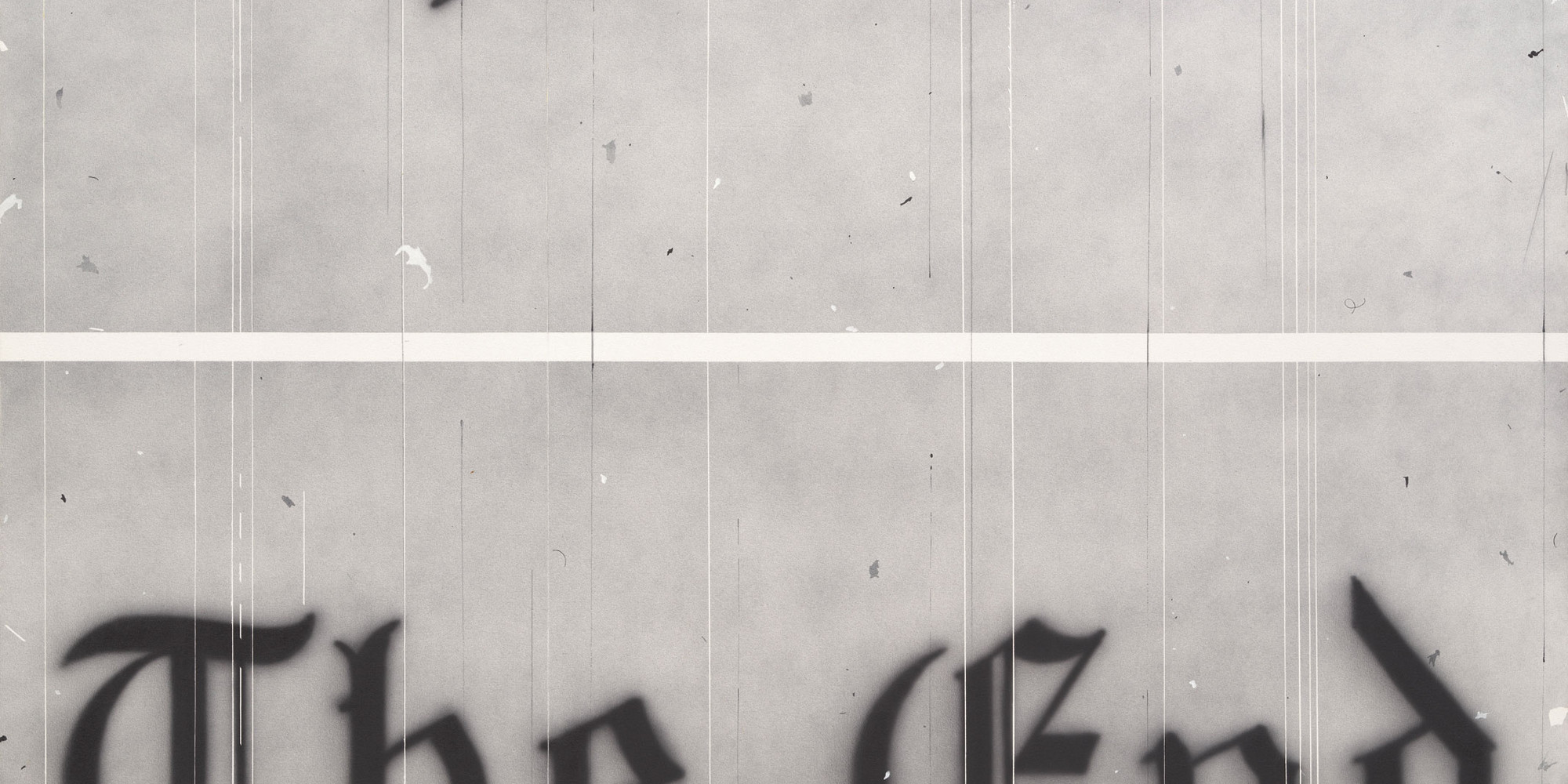

On the occasion of the exhibition ED RUSCHA / NOW THEN, MoMA commissioned acclaimed poets Rae Armantrout and Mónica de la Torre to write poems in response to Ruscha’s work, which itself dances in and around language. As Ruscha said by way of a remote introduction to the poets’ recent discussion about poetry and art at the Museum, “I’m flattered to think that my work could kickstart anybody into diving into poetry. But let’s not forget that absurdity, contradiction, and silliness have all earned seats at the table.”

Read Armantrout and de la Torre’s inspired poems below.

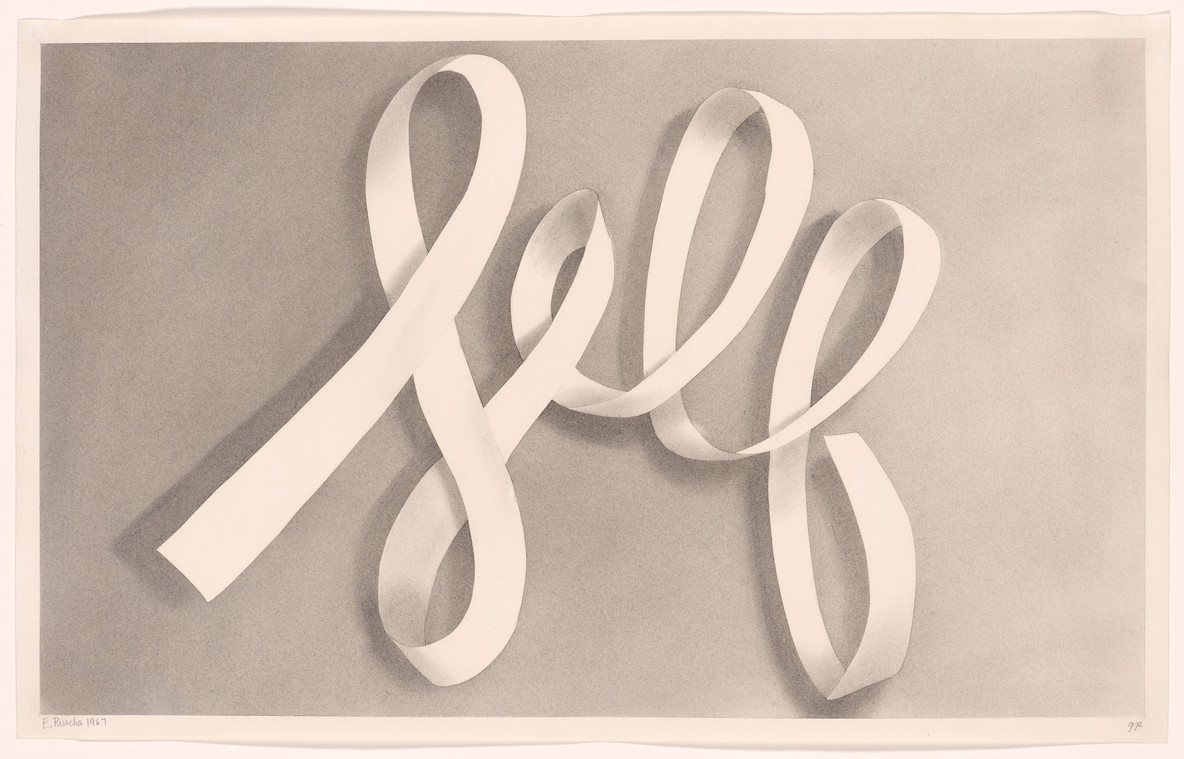

Edward Ruscha. Self. 1967. Gunpowder on paper

Rae Armantrout

When I started working on “Bandwidth” I was thinking about Ruscha’s road trips. I was moved by his paintings of lonely little gas stations in the desert. I was also struck by the way that, on some of his canvases, anomalous words hang in the air in front of mountain ranges or random buildings like crazy free-floating billboards. Ruscha and I are both Westerners. I’m from San Diego. These works remind me of the many trips I made on Route 66 when I was a kid or on highways like it as a young adult. I remember searching for radio signals from the nearest town or city amid all the static—and often finding angry-sounding preachers or politicians instead of music. This is what I was evoking in my poem—how the distance and isolation of the American West (which I like) is too often, especially now, punctuated by bursts of anger and madness.

BANDWIDTH

Inside and out,

unmoored scintillas

compete for bandwidth.

Fossil radiation

spread out around

hubs

of performed rage.

There’s no accounting for

pain’s gyrations.

At sleep’s edge

nowhere

burgeons.

Rae Armantrout is the author of more than 10 collections of poetry. Her recent collections include Finalists (2022), Conjure (2020), and Wobble (2018), a finalist for the National Book Award. Versed (2009) won the 2010 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry and a 2009 National Book Critics Circle Award. She is professor emerita at University of California, San Diego, where she directed the New Writing Series.

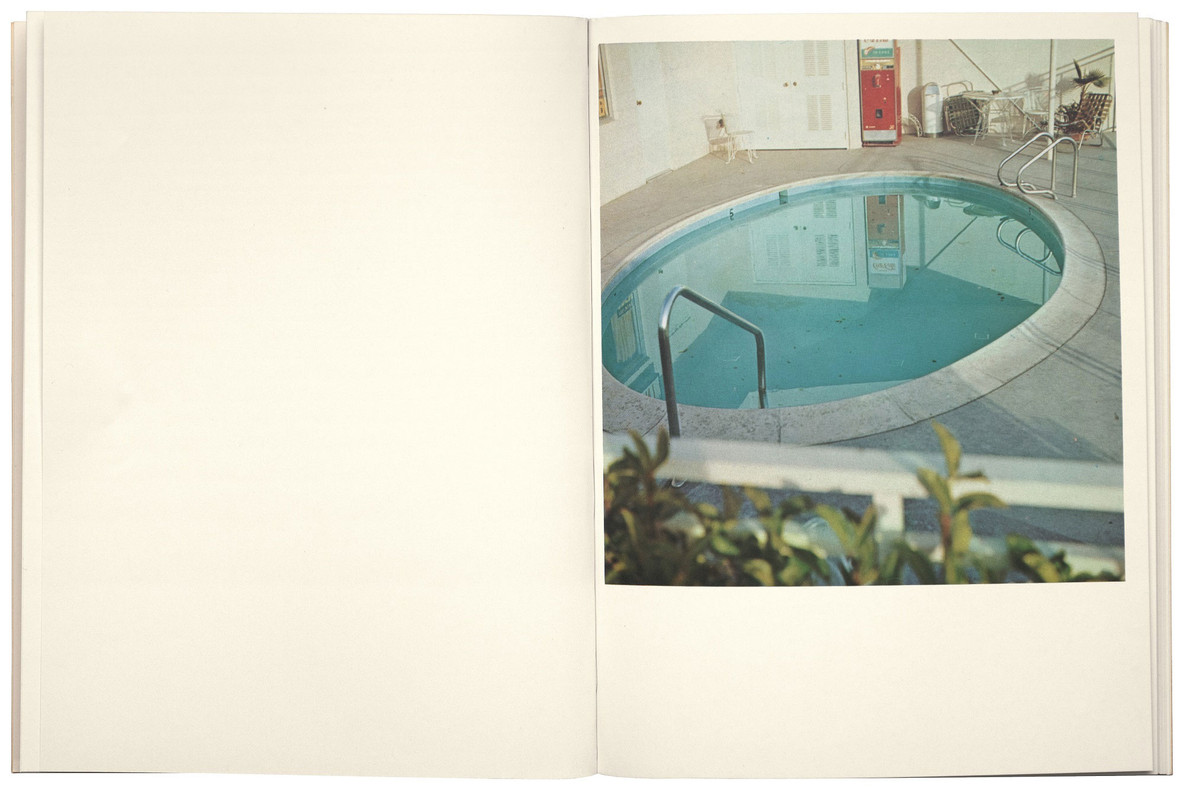

Edward Ruscha. Spread from Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass. 1968. Artist’s book

Mónica de la Torre

The idea for this poem came to me when thinking of Ruscha’s composition methods for artist’s books sequencing decontextualized images of gasoline stations, palm trees, small fires of various types, pools, etcetera. Images of pools I’ve swum in came to mind almost instantly, attached to a whole sensorium. My poem includes pools I’ve known, found pools, dreamt pools, and even those forming words in Ruscha’s paintings such as Adios (1967). I’m fascinated by the tension between sameness and difference, by the disparate elements that throw predictability out of whack.

Nine Pools

After Ed Ruscha

1

Ash raining on us while horsing

around at the square

pool near the clubhouse

in Cocoyoc. Fields all around

& the scent of burnt sugarcane.

Adults at the tennis court. Premises,

near empty. We didn’t understand.

Awareness developing in spurts.

Swam pulls me back,

I come around. No rhyme with nada.

Wham.

2

Funboy

Ibiza bohemia

inflatable kiddie pool.

3

Like swing

swim is irregular

a verb. “I have swum in that pool before.”

We forget to sculpt memories.

4

“A common reservoir of resources.”

5

Summers in Trumbull.

Swimming in circles

above ground. Chlorine

odor as pungent

as the loop

was deep, relative

to its diameter.

Vinyl. TaB &

Parliament menthol lights.

6

Drove 58 miles to the world’s

largest spring-fed swimming pool at the Balmorhea State Park.

Recent gator sightings.

FAQ: “How do I get over my fear of jumping in the water?”

7

Water pooling by the sink shapes a ghoul.

Or: liquid eye & kidney beans.

8

The Dive Motel

9

We slip into an infinity pool to cross over to another plane, so otherworldly we risk missing the bus everyone’s about to board. This part strikes the dreaming self as nonsense.

10

A tipsy Argentinian matriarch

lounging poolside takes a tumble;

her wine glass shatters on the hardscape.

The film’s opening scene.

Mónica de la Torre is a poet, translator, and scholar, and a frequent collaborator with visual artists. Born in Mexico City, she often writes across Spanish and English. Her poetry collections include Repetition Nineteen (2020), Public Domain (2008), and Talk Shows (2007). She has edited BOMB magazine and the Brooklyn Rail and is the Madelon Leventhal Rand Endowed Chair in Literature at Brooklyn College.

Related articles

-

“Alabanza: In Praise of Our Mothers, In Praise of Their Hands’’ by Gisselle Yepes

Read a poetic ode to motherhood inspired by Tina Modotti’s photograph.

Gisselle Yepes

Oct 2, 2023

-

Ed Ruscha’s “The Information Man”

Read the artist’s 1971 text, in an excerpt from the ED RUSCHA / NOW THEN exhibition catalogue.

Ed Ruscha

Sep 5, 2023