“Art must be nothing else than the expression of some sudden sensation given to us by light.”

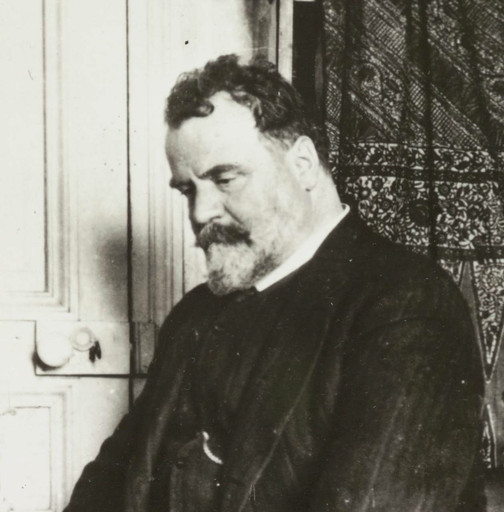

Medardo Rosso

Is sculpture boring? This question animated the life and work of Italian artist Medardo Rosso. Around the time he was studying at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera in Milan, the young Rosso encountered a text that would galvanize his career. In “Why Sculpture Is Boring,” published in 1846, the French poet and critic Charles Baudelaire skewered sculpture as a “humble associate of painting.” The sculptures found in city squares, museum galleries, cathedral niches, and public exhibitions, Baudelaire wrote, were “dry,” “cold,” and “academic,” and lacked the imagination and sophistication of pictures.

From his early years in Milan, Rosso sought to disprove Baudelaire’s assessment of his chosen medium. “Art,” stated the sculptor, “must be nothing else than the expression of some sudden sensation given to us by light. There are no such things as painting or sculpture. There exists only but life.” In his decades-long attempt to convey this credo, Rosso created around 50 distinct sculptural subjects in bronze, plaster, and wax that emphasize the vagaries of visual perception. With their rough forms, broken surfaces, and seemingly spontaneous compositions, these works prompted many writers to pronounce Rosso an “Impressionist sculptor” aligned with the painters Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro.

Like the Impressionists, Rosso often drew his subjects from urban life. In The Concierge, completed in Milan in 1883, he claimed to have portrayed the elderly caretaker of his apartment building, whom he considered “a good woman, like a mother.” One day, Rosso recalled, he found himself troubled by her scolding: “I thought, ‘Could it be that blasted old creature who keeps me from getting anything done?’ Angrily I go down to her room with my clay. I start working fast. I had in mind the effect that she had always made upon me as I went by and looked at her in passing. I managed to snatch that moment from life.” After Rosso modeled the work in clay, the clay was cast in plaster; next, this plaster version was cast in wax, with plaster applied below the wax to provide structural support. This unconventional use of wax led Rosso’s contemporaries to label him a revolutionary. At the time, artists—Rosso included—often used wax as an intermediate material in their production of bronze sculptures; in “lost-wax” casting, for instance, molten wax is replaced by bronze—and so, “lost”—during one of the final stages of the prolonged casting process. But for most artists, wax was a substance to be used in studios and foundries, not shown in galleries or museums.

After bursting onto the Parisian art scene in 1893 with a small solo exhibition where he met the sculptor Auguste Rodin and other members of the avant-garde, Rosso undertook a wax sculpture that he would eventually regard as one of his most accomplished: Woman with a Veil. “I have attempted to reproduce a ‘boulevard impression,’” Rosso explained, “a feminine physiognomy, seen in the fugitive space of a fraction of a second, but caught just as I saw it. That is my conception of art.” As in The Concierge, Rosso used wax to convey the appearance of skin, hair, and fabric. Yet his treatment of the figure is more abstract, with blurred contours and grooved facets that seem to suggest not an acquaintance carefully studied but a passerby quickly glimpsed. This effect is heightened by the planar format of the work. While Rosso sculpted The Concierge in the round, he configured Woman with a Veil as a relief, for he had come to believe by the 1890s that a sculptural “impression” could have no back, only a single front presented to its beholder.

In the 20th century, Rosso shifted from conceiving new compositions to re-casting existing works. Additionally, he devoted greater attention to the photography and exhibition of his sculptures, devising ambitious installations that incorporated his bronzes, plasters, and waxes alongside photographic prints of his own works and those of precursors and peers. Among these peers was Rodin, who by 1900 had emerged as the leading sculptor in France. Supporters of Rosso insisted that his artistic innovations exceeded (and preceded) Rodin’s, with one Rosso enthusiast asserting that the “point of arrival for Rodin” was merely the “point of departure for Medardo Rosso.” Competition aside, these friends-turned-rivals shared one conviction—that sculpture must be anything but boring.

Annemarie Iker, Mellon-Marron Research Consortium Fellow, 2020