The Deepest Cuts

A playlist from writer John Jeremiah Sullivan mines the earliest Black recordings

John Jeremiah Sullivan

Oct 15, 2020

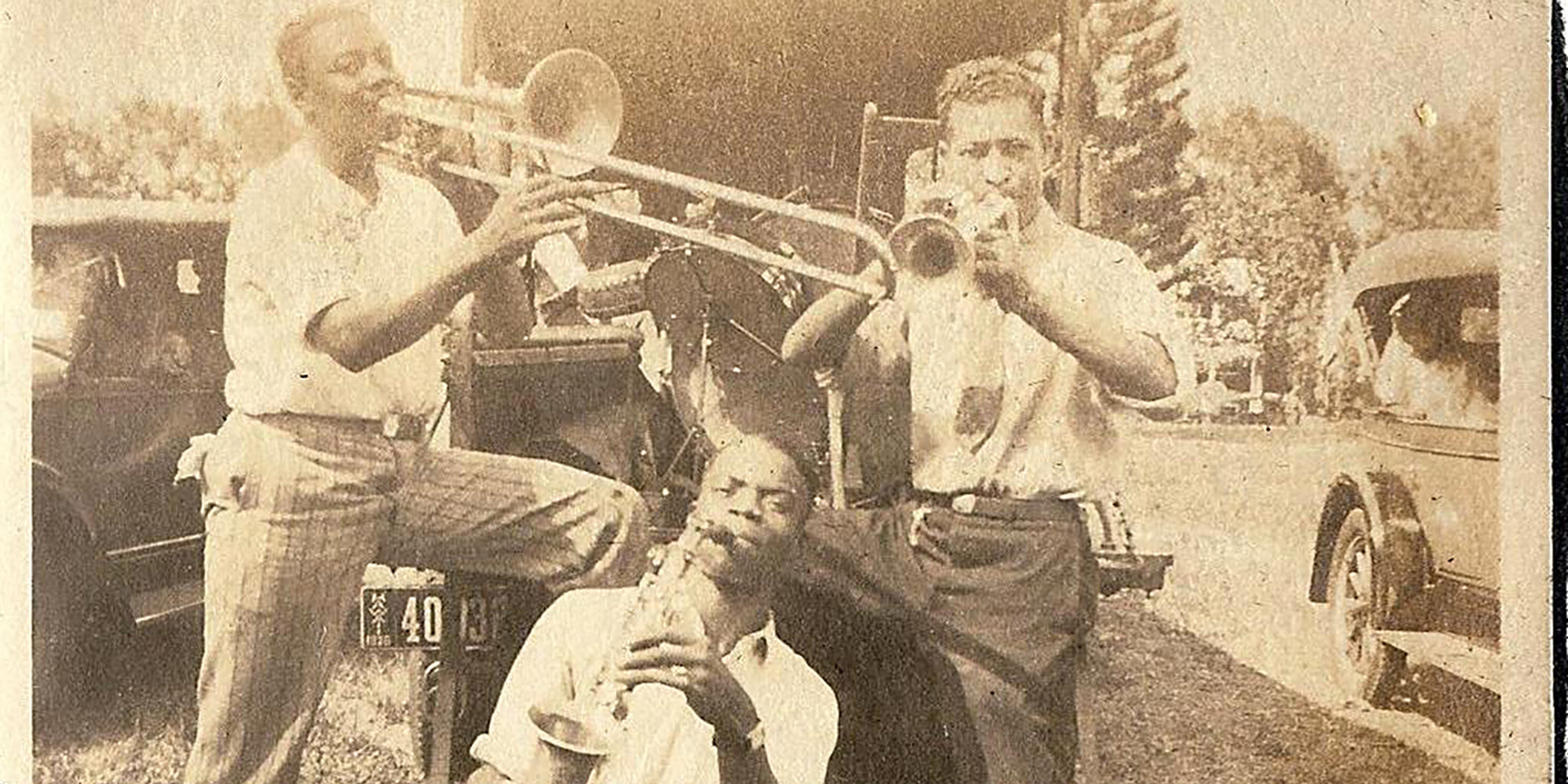

The question of what early Black music "sounded like" before the recording era (i.e., before roughly 1900, or nineteen-teens for jazz) has shadowed the study of that music from the start. There is the ocean of what we don't know, and then these little periscope views that are the records themselves. There exist also uncomfortable questions of race and theft. So often the music was performed in an interracial context, and it had evolved from a clashing of races and cultures, while always emanating in some crucial way from the Black community. How to pick those threads apart? Then there was the question of the so-called "coon songs," the incredibly popular Tin Pan Alley pop tunes that were the musical equivalent of a minstrel show. They are both horribly racist and one of the only means of access we have into the Black music of those sonically "dark" decades. Because the commercial “composers” of these pieces were ripping off Black street singers and stevedores and plantation workers so brazenly, they preserved much, but to hear it we have to wade through the well-known American muck. The other way in, the more familiar one, is to listen to singers and musicians who did live to be recorded in the last decade of the nineteenth century, or the first of the twentieth, and who played in styles that their own peers thought slightly archaic. So, we listen to them and think, okay, this is what a Black string-band could have sounded like in 1870. But if that way of thinking can be a torchlight, it can also be a will-o'-the-wisp. Musicians don't stop evolving, even the older ones. There are no pure laboratory conditions here. Which is why I love this work. For this playlist I have chosen songs in a pretty haphazard way. Some of the recordings are very early, some contain echoes of older styles, and some are just great. As with the photographs, I tried to choose songs that are (to use a word that has become familiar) "defamiliarizing."

This one is startling. 1915, the all-black Victor Military Band doing “Booster Trot (An American Absurdity).” It ain’t jazz yet, but it’s getting there. These musicians were up on the latest developments in Black popular music. (The year before, they had been the first group ever to record W.C. Handy’s great “Memphis Blues.”)

Cousins and DeMoss, “Poor Mourner,” ca. 1898.

I have listened to this song hundreds of times and with luck will listen to it hundreds

more. A strange and transporting piece of music that dissolves categories and obliterates expectations. Banjos, lyrics from hymns, ecstatic harmonies. Imagine walking between the minstrel tents and hearing this drone.

Crying Sam Collins, “Yellow Dog Blues,” 1927.

An unforgettable song. A version of the song that W.C. Handy heard a musician play in a train station (“on the guitar with the weirdest music I had ever heard”) in 1902, a year before the Florida photograph was made. Handy remembered and quoted the lyric, “Goin’ where the Southern Cross the Yellow Dog” (where two train lines met, the Southern and the Yazoo Delta). Cryin’ Sam Collins’s falsetto is equaled only by that of Skip James in the early Blues records.

Edison 694, Unique Quartet, “Mamma’s Black Baby Boy,” 1893.

Considered the oldest extant recording of a Black vocal group. You can read about the auctioning off of an actual Edison cylinder containing this song here.

Fisk Jubilee Choir, “Done What You Tole Me To Do,” 1909.

The Fisk Singers were a shaping force on American popular music in the late-19th century. For many people, it was the first time they had ever heard the “weird plantation melodies,” as the songs were invariably described. The Fisk choir also influenced the first great Black classical composer, Samuel Coleridge Taylor. He heard them in London in 1898 and described it as the most important musical experience of his life.

Ben Harney, “Mr. Johnson, Turn Me Loose,” circa 1896.

A song from my birthplace: Louisville, Kentucky. People argued for decades about whether Ben Harney was Black or white. Many Black musicians refused to believe that he was white, because his performances (of this song, in particular) sounded to their ears so authentic. Primarily for that reason we know that we are hearing in his recordings an early musical style (what we might call, “folk rag”) that is otherwise extremely hard to hear. The voiced introduction identifies Harney as “the inventor of ragtime,” which is ridiculous, but he remains a singer worth knowing about.

Bessie Jones and the Georgia Sea Island Singers, “The Titanic,” 1960.

The heroic (if complicated) ethno-musicologist Alan Lomax field-recorded this during his time on the Sea Islands. A stirring and irresistible performance of a song that the elusive Texas guitar maestro Blind Willie Johnson may have written thirty years before. Or the song could have just emerged, even before Johnson, in the way they sometimes do. “One man, John Jacob Astor, / Was a man with pluck and brains. / When this great ship was sinking, / All the women he tried to save.”

“Lord, I Love that Man,” Mamie Smith, 1939.

One of her greatest songs. I’m not sure she ever even did it in the studio, beyond this live

cinematic performance from 1939. I hope that you out there, after listening to this playlist, which includes powerful Black recordings from the 1890s(!), will be in a better position to appreciate how insane it is that Mamie’s “Crazy Blues” was the first Blues song ever recorded that featured a Black vocalist, and it did not come out until 1920.

Leora Ross, “Gambler Broke in a Strange Land,” 1927.

I’ll refrain from embarrassing myself by trying to describe this song. Leora Ross and her husband were elders in the Church of the Living God. I want to resurrect her and her choir so they can finish what they start here, a wicked moaning gospel arrangement of the classic tune “The Gambling Man.” The recording begins with it, but they only do two verses. Not even that, they repeat one verse. “I wonder where is the gambling man, / I wonder where the poor man’s gone….” Then the preaching starts and you realize the gospel had been just an intro to something equally wonderful.

Henry Thomas, “Going Up the Country (Bull Doze Blues),” 1928.

Thomas, also known as “Ragtime Texas,” often accompanied himself on the “quills,” a kind of homegrown American panpipe that was already old-fashioned. Canned Heat covered this song. (Their version is also kind of great. Alan Wilson paid his dues.)

Taylor’s Kentucky Boys, “Grey Eagle,” 1927.

A publicity photo of this group, put out by Gennett Records, deliberately excluded their Black fiddler, Jim Booker, from the image. The group’s white manager sat in for him, holding the violin. An early recording like this lets us just hear, very faintly through the ear-horn, earlier Black traditions that had developed along the East Coast. After the Civil War—when the plantation-dance economy that sustained the best Black musicians in the South had crumbled—Black string-band musicians began passing this music to white ones, and for a time it became a racially integrated genre. Read about the Black fiddler and guitar player Arnold Schultz, another Kentucky string-band player and the man with the greatest claim to having “invented” bluegrass. (Who said that about him? Bill Monroe, who was his protege.)

John Jeremiah Sullivan is a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and the Southern Editor of the Paris Review. He lives in Wilmington, North Carolina, where he works with the non-profit research incubator Third Person Project, dedicated to recovering the forgotten Black history of the Cape Fear country. His next book, The Prime Minister of Paradise, is forthcoming from Random House.