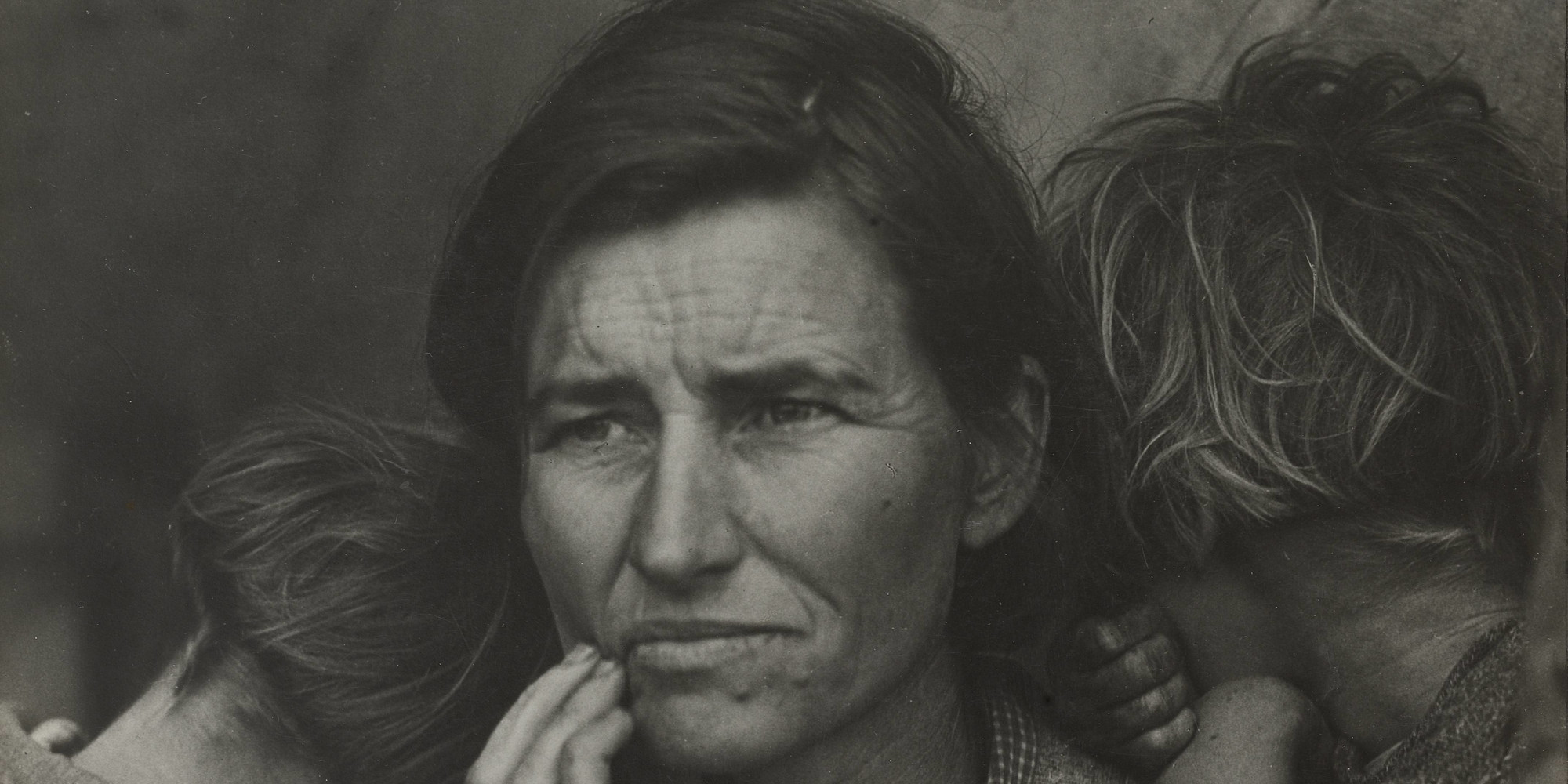

Piecing Together Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother

A MoMA curator unravels a mystery surrounding one of photography’s most iconic images.

Sarah Meister

Feb 6, 2020

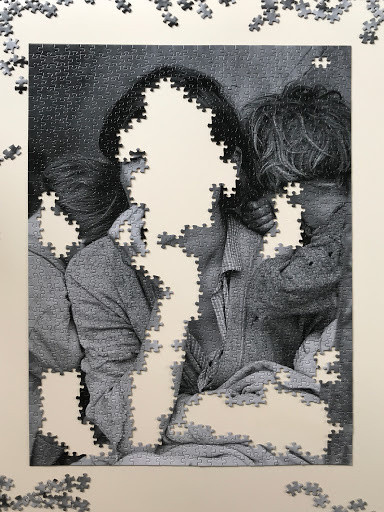

Unfinished Migrant Mother 1,000-piece puzzle

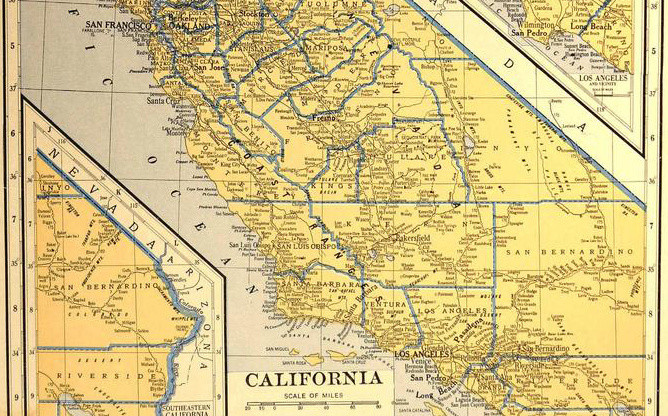

Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother—made on the edge of a frozen pea field in Nipomo, California, while she was working for the US government in early March 1936—is arguably the most famous photograph ever made. It will be included in the exhibition Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures along with 100 other photographs from across her career. And yet, while I was writing this little book about Migrant Mother, there were so many pieces that simply didn’t fit.

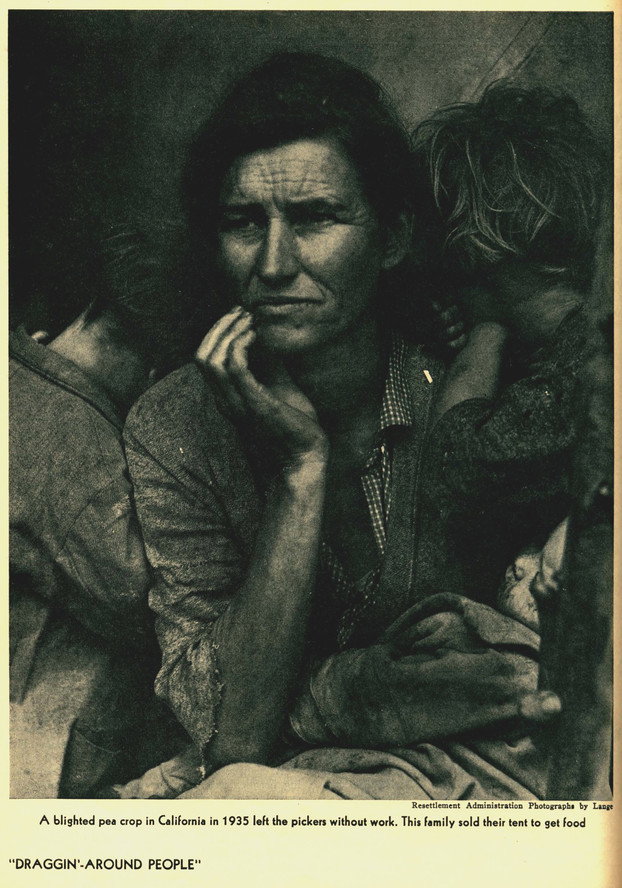

“Draggin’-Around People,” Survey Graphic (September 1936)

The photograph was one of seven that Lange made of Florence Owens Thompson and her children, although the exact number of negatives she exposed has been recorded repeatedly as five (even by Lange, but believe me, there are seven, although she sent only the five best negatives to Washington, DC). In September 1936, Lange and her husband, the agricultural economist Paul Taylor, published the image with this caption: “A blighted pea crop in California in 1935 left the pickers without work. This family sold their tent to get food.”

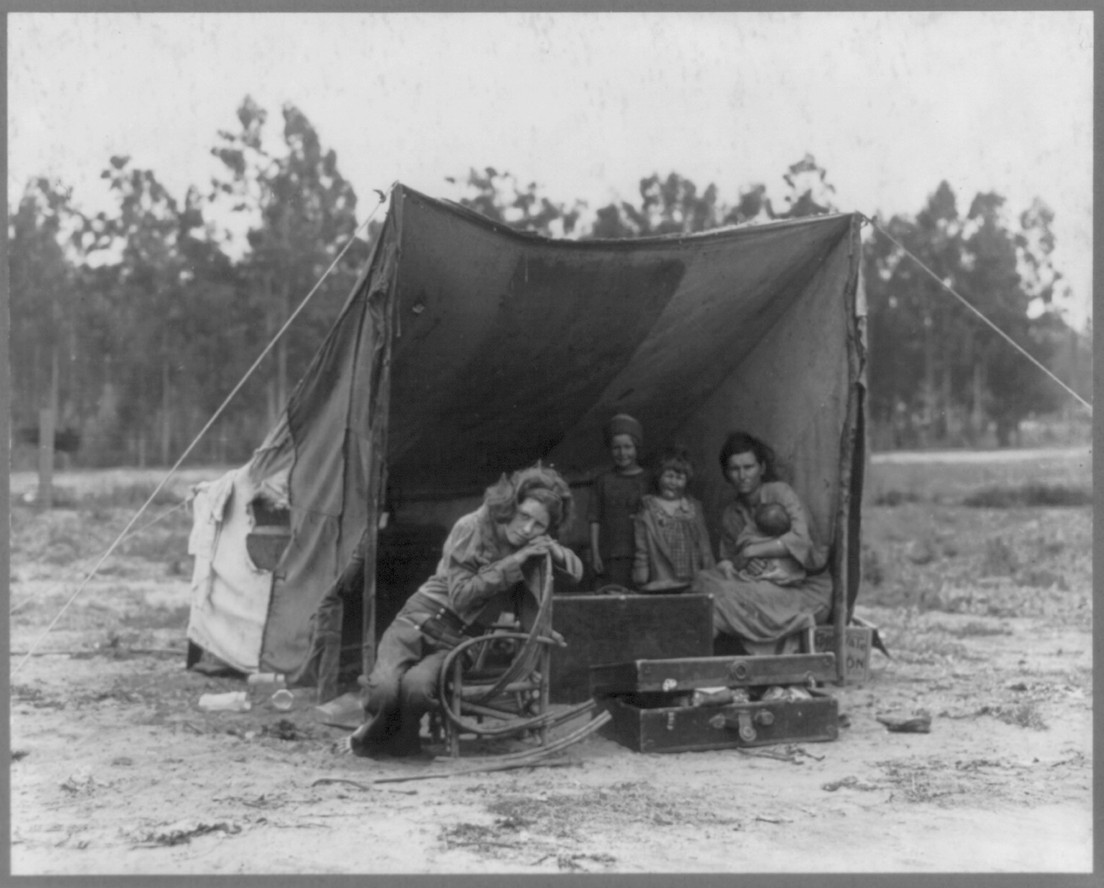

Dorothea Lange. “Nipomo, Calif. March 1936. Migrant agricultural worker’s family. Seven hungry children and their mother, aged 32. The father is a native Californian.”

Surely Lange knew she had made what was already her most famous image just six months earlier (perhaps that’s simply a typo), but the tent is plainly visible in this variant.

Dorothea Lange. “Nipomo, Calif. Mar. 1936. Migrant agricultural worker’s family. Seven hungry children. Mother aged 32, the father is a native Californian. Destitute in pea pickers camp, because of the failure of the early pea crop. These people had just sold their tent in order to buy food. Most of the 2500 people in this camp were destitute.”

And in this one, published in the New York Times on July 5, 1936, with this (largely fabricated) caption: “Gazing into the Future and Seeing Dust. A refugee family, from the drought area, camped near San Jose, Calif., for the duration of the pea harvest. Then, with the price of a tankful of gasoline, they will strike their tent and wander on.” On August 30, 1936, the New York Times got the crop wrong, describing Thompson as “A worker in the ‘Peach Bowl.’”

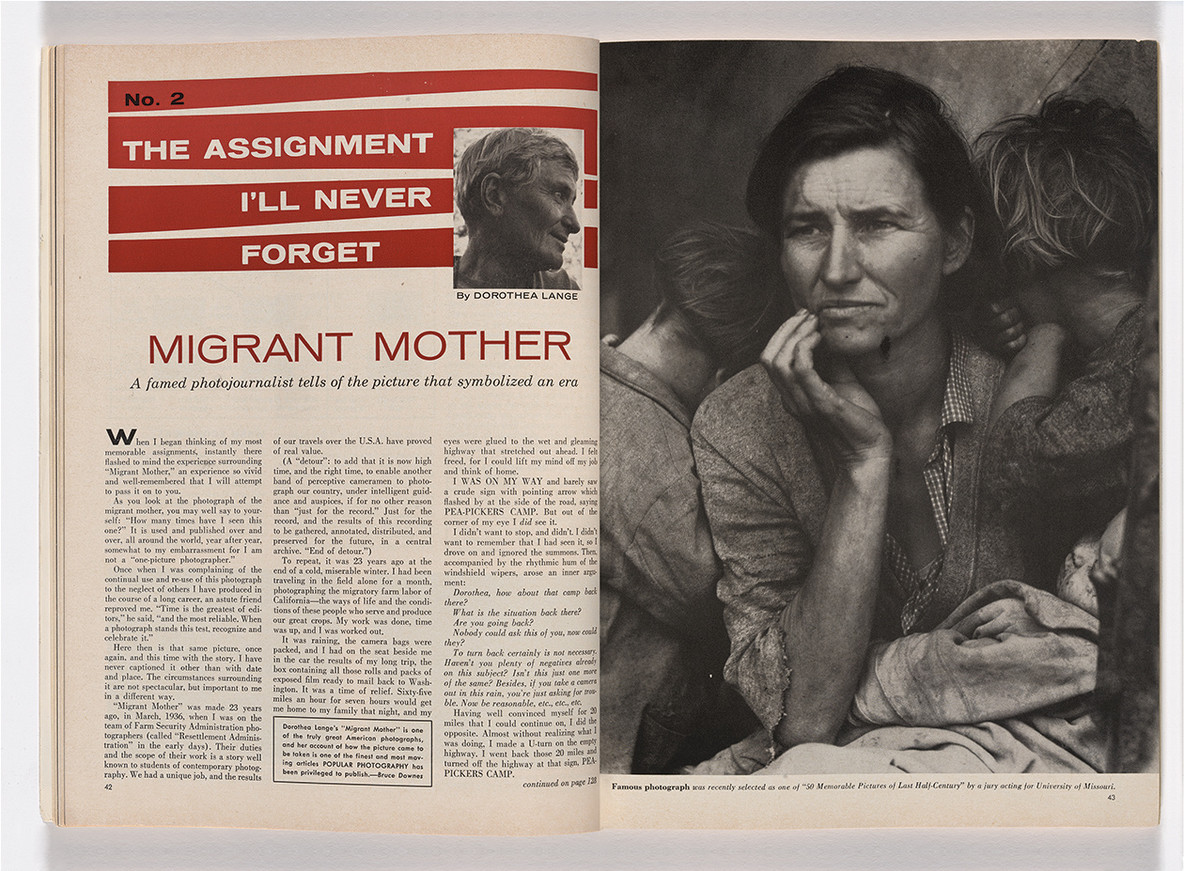

“The Assignment I’ll Never Forget: Migrant Mother,” by Dorothea Lange, Popular Photography (February 1960)

It wasn’t until June 1960 that Lange told her side of the story in an article titled “The Assignment I’ll Never Forget.” It was almost a quarter century later, so we’ll forgive a few factual inaccuracies, but in it we learn the key to all these errors: After a month on the road she was in a rush to get home. As she recalled, “I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions…. I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was 32. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food.” Thompson’s family members so strongly objected to this account—feeling that it discounted her ability to provide for them—that I decided to head to the Library of Congress to see what I could discover there.

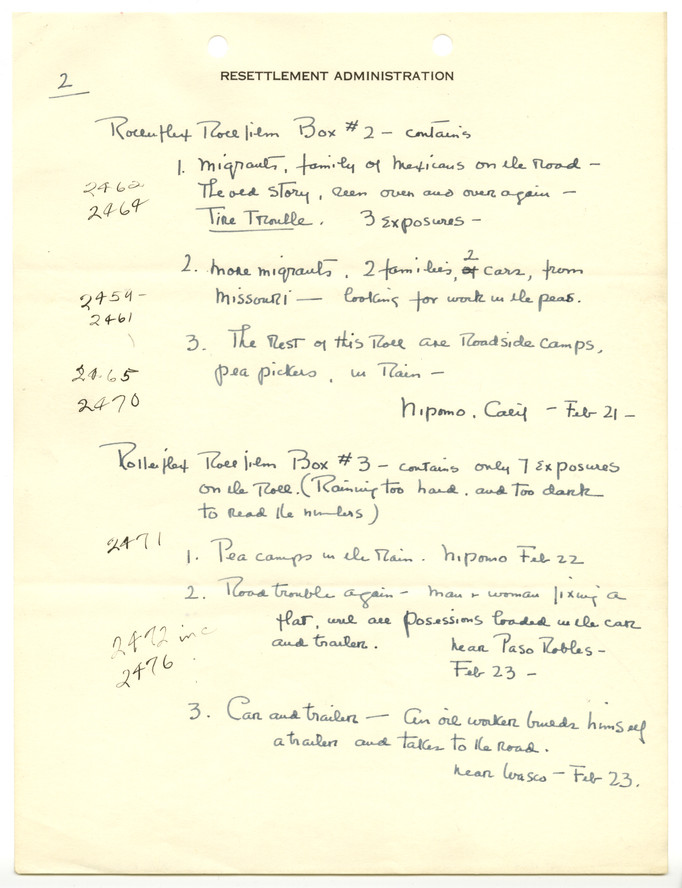

Dorothea Lange’s captions for Lots 344–345 (February 1936)

In the early days of the Resettlement Administration (later the Farm Security Administration), photographers would send their film and field notes to Washington, DC, where they were sorted into “Lots”: film was processed, field notes typed onto caption sheets. The best images were printed and mounted onto file cards along with their typed captions. But nothing in Lange’s field notes corresponded to the typed captions for these images, and the only mentions of Nipomo were in February 1936.

We found the answer by looking through the correspondence of Roy Stryker, head of the Information Division of the Resettlement Administration (later the Farm Security Administration) and Dorothea Lange’s boss. Lange writes to him from Bakersfield on February 24, explaining that she “had to get out of the San Luis [Obispo] area with the job unfinished before the road washed away. Will stop there again on the return trip.” On March 2 she writes from Los Angeles, saying that she has two more days’ work there, and will then head to Santa Paula. Fittingly, she pastes into this letter a Chinese proverb: “The palest ink is better than the most retentive memory.” There is no additional correspondence from this trip: as Lange wrote in Popular Photography, she was in a hurry to get home.

The San Francisco News, Tuesday, March 10, 1936

On April 18 Stryker writes to Lange: “Incidentally, you have sent in some swell stuff. We are very much pleased with it. We shall need captions for some of the prints.” On April 24 she responds with the news that “our photographs of migratory workers at Nipomo were published not only in the San Francisco News but were distributed through the labor press and smaller papers of the state by the United Press, the Western Newspaper Union and the Newspaper Enterprise Association. Enclosed you will find sample copies.” Alas, these United Press reports are the source of all the confusion: they describe the general circumstances in the camps, not Thompson’s family, yet in the absence of any other information they were used to develop captions for the series.

Bill Ganzel. Migrant Mother, Florence Thompson, and her daughters Katherine McIntosh, Ruby Sprague and Norma Rydlewski at Norma’s House, Modesto, California. June 1979

I am just one of many interested in unraveling the mysteries of this photograph and our varied responses to it. It was decades before the public learned that Thompson was Cherokee: we now grapple with how its reception would have differed if that had been known. The story is enriched by the efforts of Bill Ganzel, who interviewed and photographed Florence Owens Thompson and three of her daughters in June 1979, as part of his project Dust Bowl Descent. These contexts continue to expand, through the poetry of Tess Taylor and the art of Sam Contis, and, I hope, through those inspired by this exhibition to look again at Lange.

Related articles

-

Gallery Hang

New Ways of Looking at MoMA’s Earliest Films and Photos

Two curators tell us what goes into a gallery that reflects how image breakthroughs impacted modernism.

Sarah Meister, Rajendra Roy

Jan 24, 2020

-

Solving the Mysteries of the Hampton Album

A team searches for answers to a photography collection’s enigmas.

Jane Pierce

Sep 10, 2019