Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s The Killing Machine

A MoMA conservator installs an unsettling kinetic sculpture inspired by a Franz Kafka story.

Sean Yetter

Jan 2, 2020

The gallery is dark. There’s only a small spotlight revealing a red button with a note that reads “press.”

Museums rarely encourage visitors to touch the art. And this work appears to be a mechanized torture apparatus, so it’s to be expected that a visitor may pause before reaching out.

“It’s a little ominous. [The artists] wanted that hesitancy of ‘should I press it?’” recounts associate media conservator Peter Oleksik, who has spent more than two years preparing The Killing Machine (2007) for MoMA’s reopening this fall.

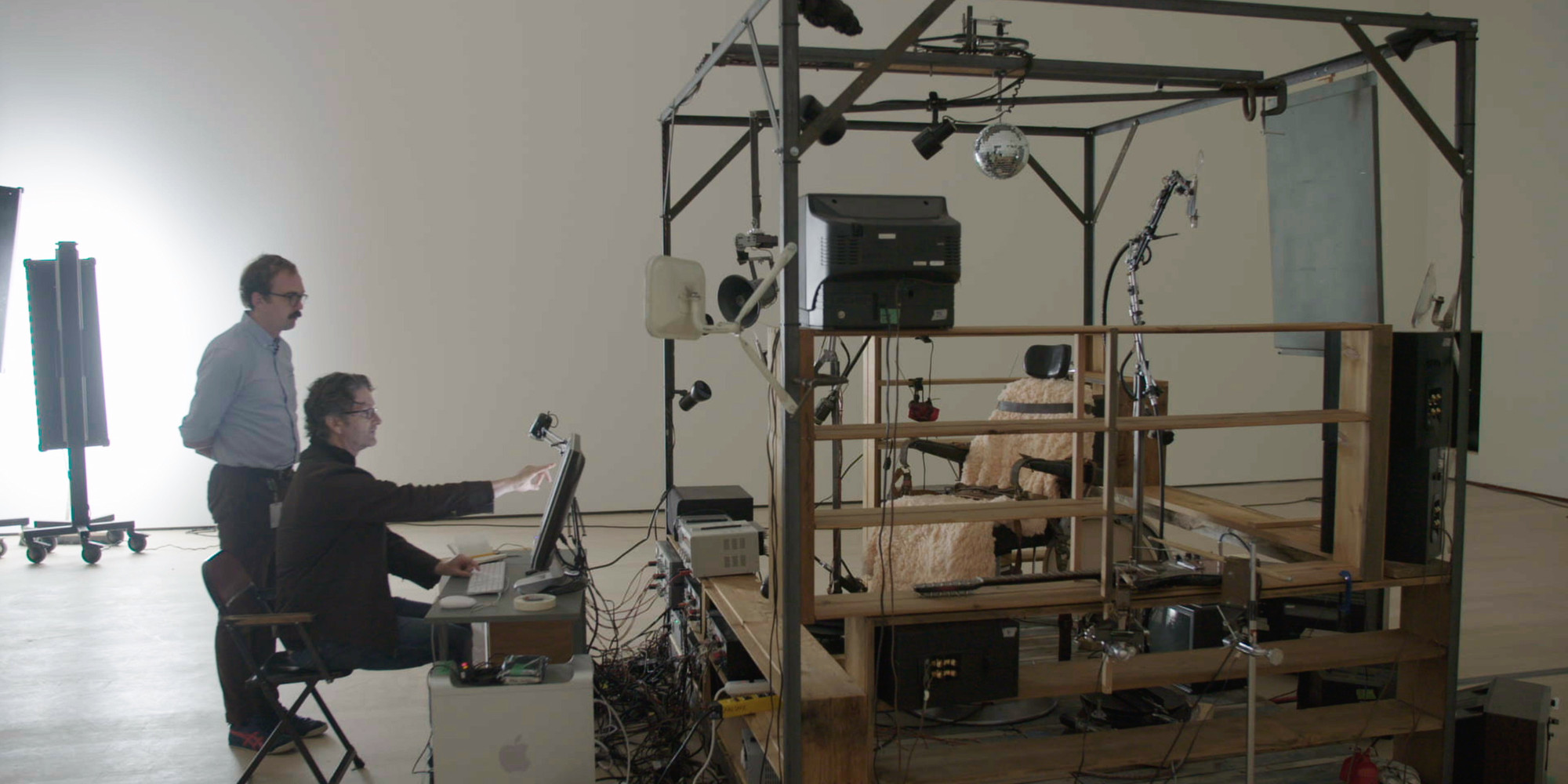

A kinetic sculpture by the artists Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, The Killing Machine was inspired by a contraption from “The Penal Colony,” a short story written in 1914 by Franz Kafka, who often explored the psychic toll of modern society. In his story, Kafka described a machine that tattooed prisoners with their sentences. Cardiff and Miller positioned a dentist chair underneath two robotic arms that perform their duties on the would-be victim, surrounded by cathode-ray tube TVs and a disco ball, while a symphony of discordant music and an electric guitar beaten by a drumstick serenade the grisly goings on.

“It’s really a puppet show,” says Oleksik about the dance between the two robots (somewhat affectionately named R1 and R2) and the numerous audiovisual components that bring the Cardiff-Miller work to life—often with obsolete technologies, such as tube TVs, which create static patterns no longer possible with more up-to-date monitors.

After working with the artists for several years to ensure that The Killing Machine was ready for MoMA’s 2019 reopening, Oleksik’s ultimate goal is to preserve the sculpture for the future. “When my successor 50 to 100 years from now goes to install this piece, [I need to ensure that] they are operating with a wealth of information,” Oleksik says. Grinning, he adds, “I don’t want to sit in the dentist’s chair.”

Related articles

-

Conservation Stories

Prolonging the Life of an Image from the Dawn of Photography

A MoMA conservator thoughtfully treats a daguerreotype by Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey.

MoMA

Dec 6, 2019

-

Conservation Stories

Paula Modersohn-Becker’s Self-Portrait with Two Flowers in Her Raised Left Hand

Sturgeon bladders and surgical tools breathe new life into a painting.

MoMA

Sep 12, 2019