The Post-it

We assess the stickiness of a little square of paper across departments at MoMA.

Jennifer Tobias

Dec 23, 2019

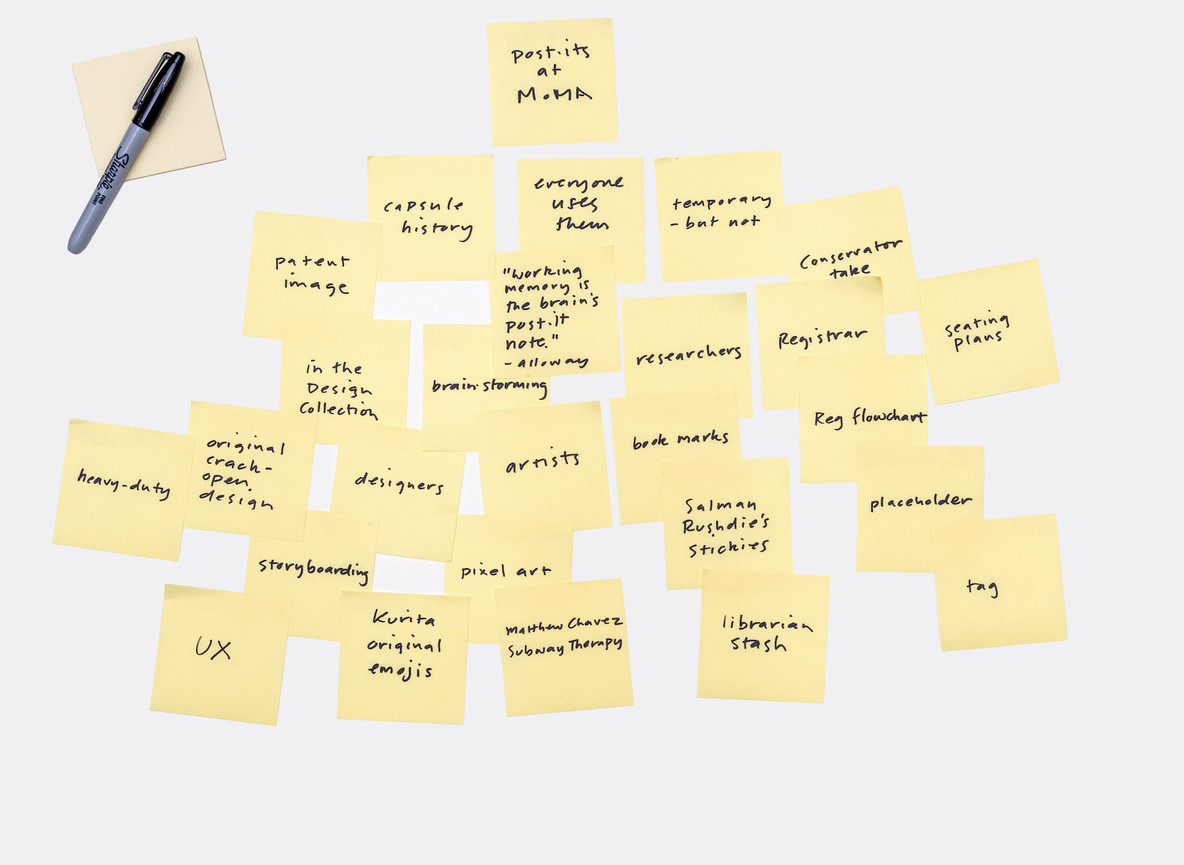

“Everyone uses them,” I write. Pull. Stick. Repeat. Soon I’ve worked up a canary yellow thought cloud about sticky notes at MoMA. For curators, artists, designers, conservators, registrars, researchers, and others, Post-its (as they are branded) are the tools of museum work.

“Many of us cannot imagine life without these ‘stickies,’” said Paola Antonelli, a senior curator in MoMA’s Department of Architecture and Design, upon adding Post-its to the Museum’s collection in 2004. “The original one is square, almost an expression of rationality, and yellow, to attract attention—and to be easy to photocopy.” It’s “one of the dozens of examples of everyday design the collection set out to celebrate.”

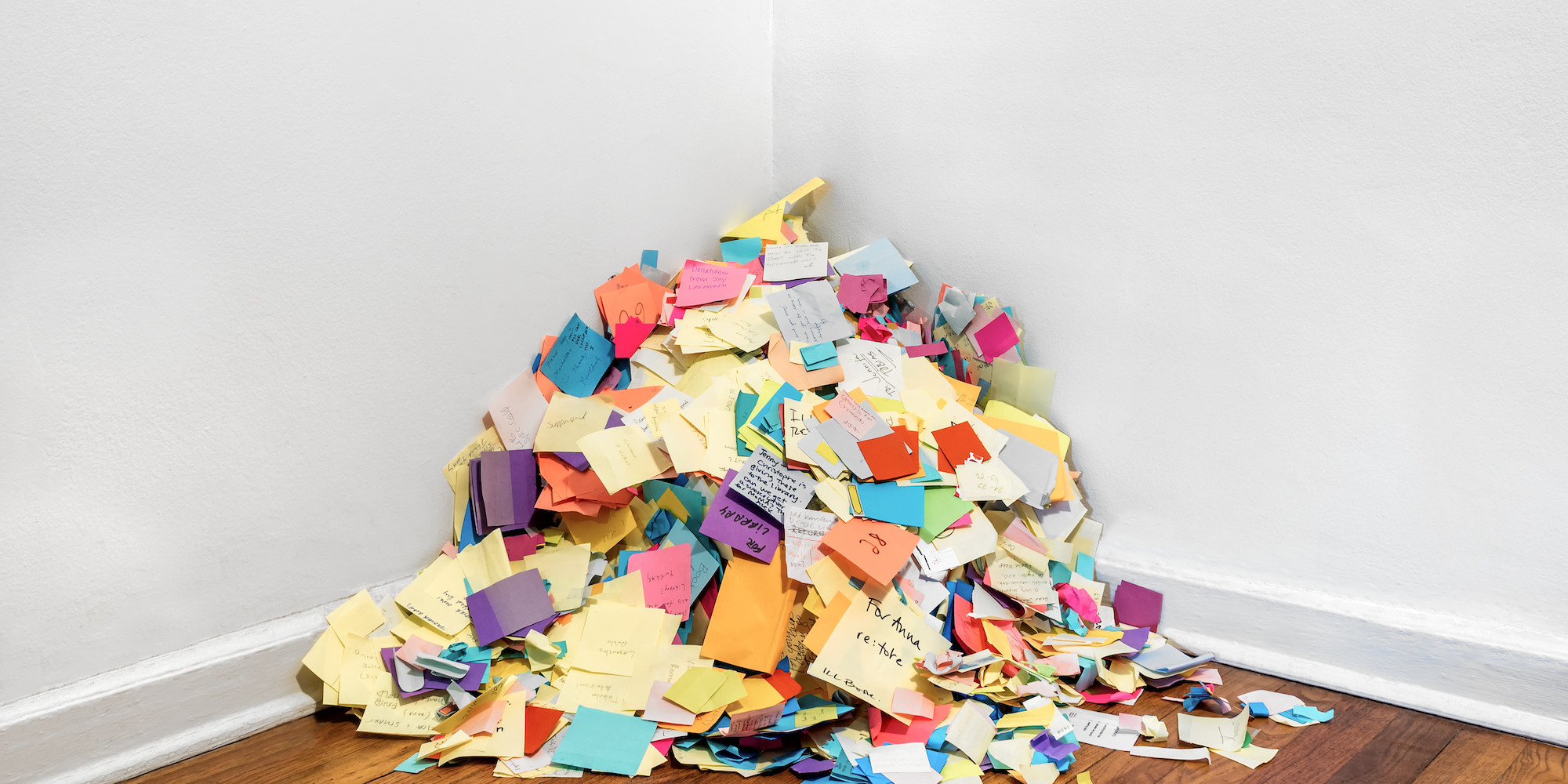

Post-its used to outline this article. Photo: Alejandro Merizalde

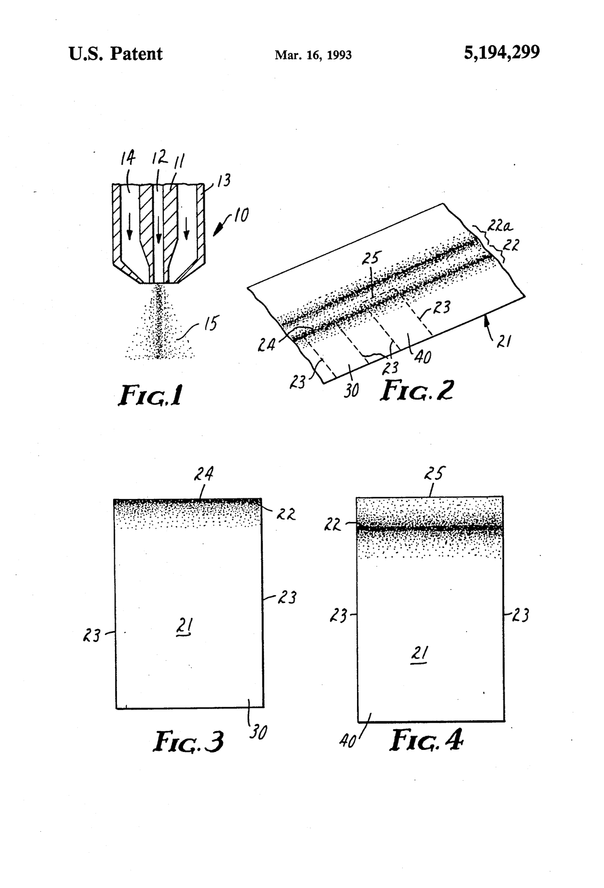

Described in its 1993 patent as “sheet material having the ability to be applied to paper and removed therefrom [with a] pressure-sensitive adhesive...resulting in a non-repetitive pattern of adhesive islands,” Post-its gave the world repositionable, removable notes. By most accounts they were developed through a series of happy accidents by 3M scientists Spencer Silver (who made a weak adhesive while searching for a strong one) and Art Fry (who made use of it as a hymnal bookmark).

Arthur L. Fry, Patent #5,194,299, 1993

Since the product’s introduction, 3M has developed over 20 variants, including “extreme” Post-its suitable for rough, wet, or outdoor surfaces, and apps for simulating and digitizing analog Post-its.

MoMA’s Post-its of record reside in collection storage, but their brethren seem to be everywhere, from galleries to the library.

To feel the pull of a Post-it, step into Rivane Neuenschwander’s Work of Days (1998), currently on view in Surrounds: 11 Installations. The work takes the shape of a room, with walls and floors coated in a light adhesive. Like Post-its, the adhesive attracts dust and other residue through use. Said to be a meditation by the artist on the ephemerality of life, the work shows how we leave earthly traces despite our apparent transience. These traces include several actual Post-its, sticking around on the installation floor.

Rivane Neuenschwander. Work of Days. 1998

Rivane Neuenschwander. Work of Days (detail). 1998. Photo: Alejandro Merizalde

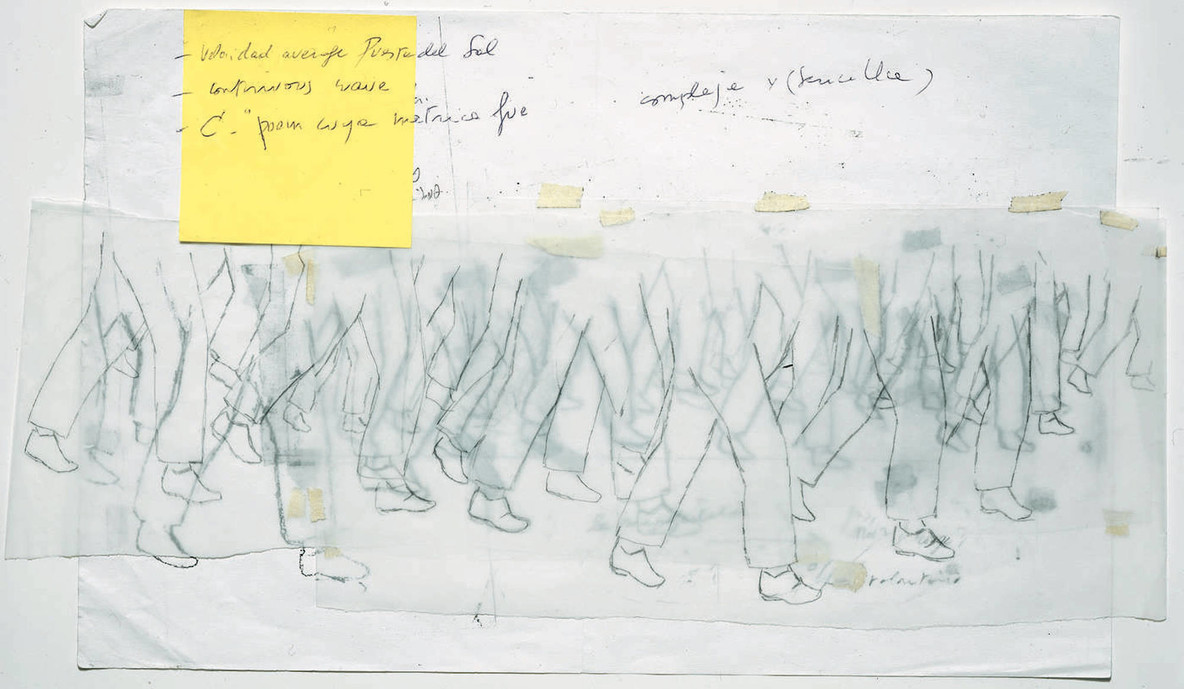

A Post-it is incorporated into another work in MoMA’s collection: Untitled (2002), by Francis Alÿs. A Post-it flies like a flag over a procession of traced, walking legs. Both note and taped-on legs are repositionable, suggesting the artist’s process for developing and directing the public performance When Faith Moves Mountains (2002).

Francis Alÿs. Untitled. 2002

Another work speaks to the rearrangeable nature of the Post-it’s original square format. Shigetaka Kurita’s original 176 emoji, on view in the Cullman Education and Research Building, were based on a 12 × 12 square grid—introducing grid-based design into the era of 8-bit computer graphics.

Magnet board for designing emoji at MoMA’s Art Lab. Photo: Jennifer Tobias

Or go old-school and use Post-its to simulate one of Frederich Froebel’s 19th-century pedagogical toys, also part of the design collection. Several of these incorporate packages of square colored paper intended for cutting, weaving, arranging, and folding.

Milton Bradley, Co. Gift 18: Folding. c. 1920. Photo: John Wronn

Fanny Katchline went all out on folding, as seen in her square-shaped album.

Fannie E. Katchline. Paper folding (Kindergarten material based on the educational theories of Friedrich Froebel). c. 1890

The album, dated to the 1890s, has held up well over the years. But how do modern Post-its compare? To find out, associate paper conservator Annie Wilker took a professional look.

Paper conservators are wary of Post-its, Wilker said. Citing a number of studies, she explained how those ephemeral-looking slips really do stick around. First, there’s the glue residue: even a few seconds of adherence leaves a magnet for grime. Moreover, one type of adhesive gets stickier over time while another leaves stains. Adhesive even interacts with coated papers, as her colleague, conservator Erika Mosier, points out in a study of blue painter’s tape. In it, Krista Lough, former Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Conservation, says to watch out for fragile papers such as newsprint, too: removing a Post-it can take an adhesive-shaped piece of paper with it. Then there’s the low-quality, colored paper they’re made of, which is prone to brittleness, fading, and bleeding.

That said, Wilker observed that the Post-its of record in MoMA’s collection, acquired 15 years ago and stored in good conditions, are largely unchanged. Upon examination, their color remains strong and the adhesive shows no evidence of spreading, staining, or extra stickiness.

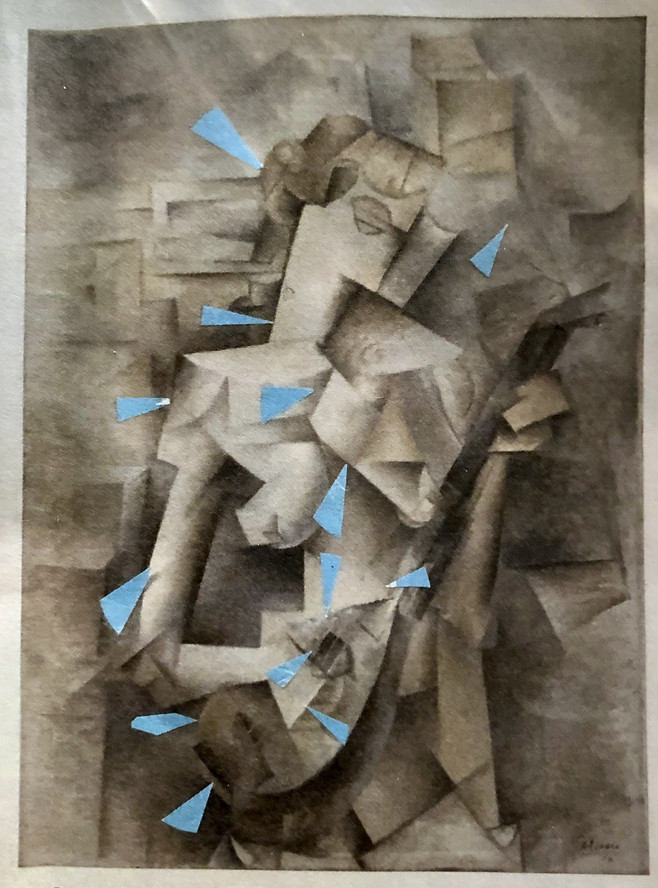

Despite misgivings, conservators certainly use Post-its, though not on the artworks themselves. Wilker referred me to senior conservator Anny Aviram, who uses tiny, pointy ones on a reproduction to indicate where a painting needs attention.

Post-its on a reproduction of Pablo Picasso’s Girl with a Mandolin (Fanny Tellier) (1910) indicate spots for conservator attention. Photo: Anny Aviram

Recently, conservators have even been sighted tagging the newly installed galleries. Associate registrar Eliza Frecon caught some Post-its on camera, with cryptic notes such as “5fc,” reminding installers and electricians about maximum light levels acceptable for a particular work.

A conservator’s note indicates acceptable light levels for Bill Traylor works being installed in Gallery 521: Masters of Popular Painting. Photo: Eliza Frecon

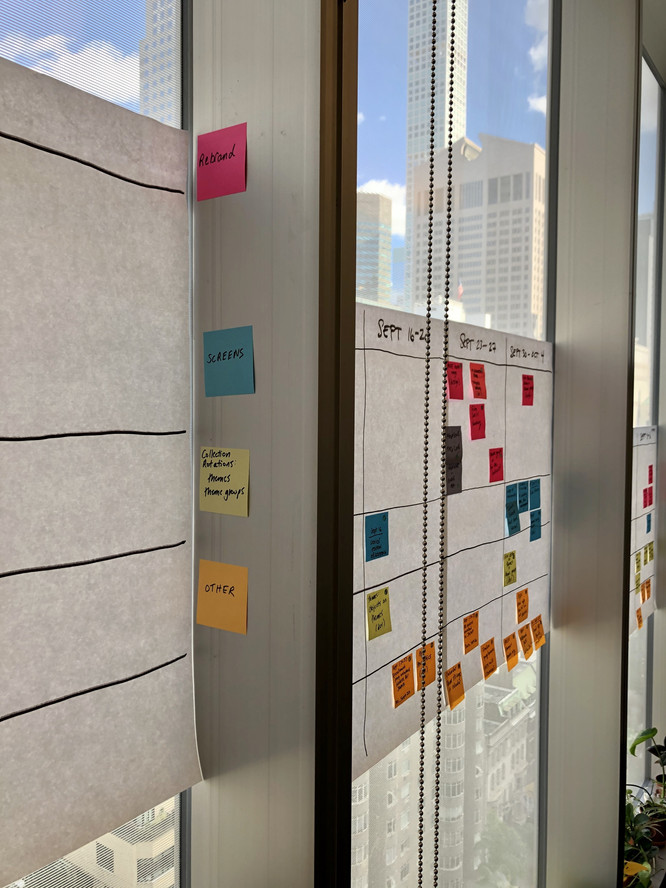

Post-its seem to be everywhere behind the scenes, too. The Digital Media department in particular always seems to be covered in this very analog medium, with easel-sized sheets spawning endless multicolored offspring. Shannon Darrough, MoMA's director of Digital Media, unearthed a stash from a recent project, with one in particular standing out for data intensity and ambition. On the sheet (itself a giant Post-it), a swarm of smaller, color-coded squares are inscribed with projects and plotted along axes of Impact and Difficulty.

Post-it production timeline in MoMA’s Digital Media department. Photo: Jennifer Tobias

The award for most creative use of Post-its at MoMA certainly goes to Paola Antonelli, who brought them into the collection. In a magazine profile photograph, she proposes them as office wear. In principle it’s Good Design: breathable and sustainable, stickywear fits any body type and comes in a variety of colors. Though it hasn’t caught on, a framed copy of the photo is proudly displayed at her parents’ house.

Paola Antonelli, Senior Curator, Department of Architecture and Design, and Director of Research and Development, 2003. Photo: Nigel Parry/The Licensing Project

Finally, Post-its are popular at the MoMA Library too, even though they should not be applied to collection materials. Researchers use them to make outlines, mark edits, and hold brief comments. Abandoned Post-its cumulate there, little trail markers leading through the uncharted wilderness of human thought.

Post-its discarded by library researchers. Photo: Alejandro Merizalde

In their 2014 book Understanding Working Memory, research psychologists Tracy and Ross Alloway agree, concluding that working memory is “our brain’s Post-It note.” It follows, then, that Post-its show the brain working to select, sort, sequence, consolidate, and further formulate ideas. Artist Francis Picabia never lived to see a Post-it, but his conviction that “our heads are round so our thoughts can change direction” suggests he might have appreciated them.

Related articles

-

Materials

Heavy Metals: Conserving Andy Warhol’s Gold Marilyn Monroe

Two painting conservators discuss the particular challenges of getting Marilyn gallery-ready.

Michael Duffy, Emily Mulvihill

Sep 13, 2019

-

Materials

Blue Painter’s Tape

Artist Carmen Winant and conservators Erika Mosier and Krista Lough discuss the use of blue painter’s tape in Winant’s My Birth.

Carmen Winant, Erika Mosier, Krista Lough

Jul 25, 2019