Throughout the run of Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925 (December 23, 2012–April 15, 2013) we invited contemporary artists to pick a work and say briefly what they find most compelling about it.

Posts tagged ‘Gabriel Orozco’

Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925: Contemporary Artists Discuss Selected Works

Off the Shelf: Design Finds

MoMA Offsite: Across the River, Across the Pond

Institutions that engage in munificent and far-reaching lending forge important collegial relationships with one another, and in the process help to create a network of public spaces with dynamic, diverse programming. Rarely, however, are these relationships sanctioned in any official capacity, which is what makes the affiliation between MoMA and P.S.1 so special. The two joined forces in 2000, with the goal to “promote the enjoyment, appreciation, study, and understanding of contemporary art to a wide and growing audience.” In the last ten years the institutions have worked together in many ways, but 1969, an exhibition on view at P.S.1 through April 5, is the first time that a group exhibition at the Long Island City center has been drawn entirely from MoMA’s collection.

Occupying an entire floor at P.S.1, the exhibition features some eighty objects representing all seven of MoMA’s departmental collections plus the Museum Archives. I was delighted to discover dozens of works for the first time, as well as to embrace long cherished images that I had never before seen in person. Just as gratifying was seeing several works—works that MoMA visitors are surely familiar with—in a new context.

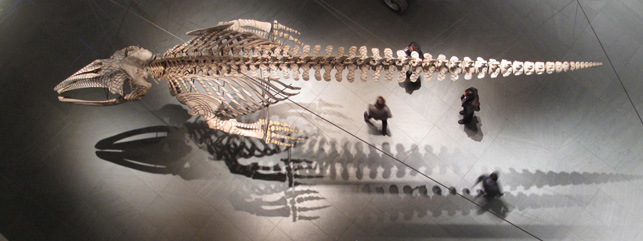

Biography of a Whale

Gabriel Orozco. Installation view of Mobile Matrix (2006) at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Graphite on gray whale skeleton. Biblioteca Vasconcelos, Mexico City. Photo: Charles Watlington. © 2010 Gabriel Orozco

Every work at a museum may compel a viewer to wonder how it was made or where it came from. However, there are some works whose genesis provokes a special degree of collective fascination. Gabriel Orozco’s Mobile Matrix, currently on view in MoMA’s Gabriel Orozco exhibition, is one such work.

Museum Kids: Keeping It Real

Ethan is delighted by the Formula 1 Racing Car hanging in the Education and Research building lobby.

Just after I’d accepted my job at MoMA, I brought my six-year-old son along with me to visit. He entered the Marron Atrium and, with a sweeping, 360-degree review and an air of finality, announced, “I like your new museum, mom.” Good thing it passed muster.

I often wonder what it is to grow up in a museum. From the time he was two, Ethan had a steady diet of contemporary art. Bridges made of Meccano sets; entire cities built of pots and pans; rooms glowing with neon tubes; walls covered with “parades” of people made from ripped black construction paper; cars and trailers jack-knifed, emerging out of a museum plaza; metal squares on the floor, perfect for playing hopscotch—to Ethan, art always seems full of possibilities.

His own “work” attests to that, as we find colored-tape installations proliferating throughout our apartment—often accompanied by an objet trouvé repurposed in interesting ways, or a small love note to mom and dad.

Ethan, now nine, accompanied me to the office last week.

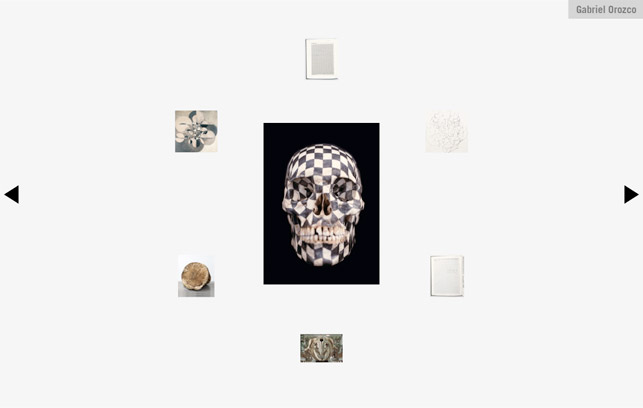

The Gabriel Orozco Website: Stacking the Deck

The Gabriel Orozco website

“There is no way to identify a work by Orozco in terms of physical product. Instead, it must be discerned through leitmotifs and strategies that constantly recur, but in always mutating forms and configurations.”

—Ann Temkin, the Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture, from the Gabriel Orozco exhibition catalogue

Uh oh.

That was my first reaction to Ann’s description of Gabriel Orozco’s practice. We were researching the artist, looking for persistent visual themes, devices, or elements in his work that could be used to anchor or accent the design of the exhibition website. The works that I was familiar with at the time—Black Kites, Citroen DL, the Atomist series—didn’t share obvious aesthetic connections, so I assumed that a common thread would be found in the pages of the catalogue. But here Ann was saying that Orozco’s mercurial practice provided little in the way of overt physical similarity. And that, given a looming deadline, was daunting. More fruitful were meetings Allegra Burnette (Creative Director of Digital Media) and I had with Ann and Paulina Pobocha, a curatorial assistant who worked on the exhibition. Though we didn’t come up with concrete ideas about the look of the site, the curators did provide insight as to its desired spirit: simple and playful. Simple, because the curators wanted something that was easy to use and understand, and playful, because what better way to conceptualize a website dedicated to an artist whose work has included the customization of both billiard and ping pong tables (Carambole with Pendulum, 1996, and Ping-Pond Table, 1998) and chess- and checkerboards (Horses Running Endlessly, 1995, and Lemon Game, 2001)?

If you are interested in reproducing images from The Museum of Modern Art web site, please visit the Image Permissions page (www.moma.org/permissions). For additional information about using content from MoMA.org, please visit About this Site (www.moma.org/site).

© Copyright 2016 The Museum of Modern Art